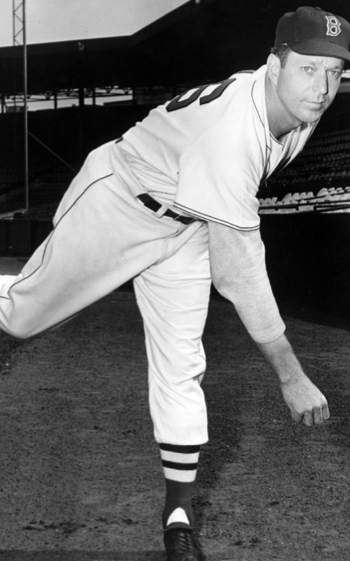

Ellis Kinder

In January 1956, a few months after Ellis Kinder had been sold by the Boston Red Sox to the St. Louis Cardinals after eight years in the Hub, his friends threw him an Appreciation Night at Boston’s Sheraton Plaza Hotel. In attendance were the governor, the mayor, several former teammates, and 600 assorted guests. Birdie Tebbetts, who had caught Kinder in the late 1940s and was then managing the Cincinnati Reds, served as toastmaster. Birdie had caught Hal Newhouser and Dizzy Trout in Detroit, Mel Parnell in Boston, and Bob Lemon, Early Wynn, and a late-career Bob Feller in Cleveland, but he told the gathered throng that he never caught a better pitcher than Kinder. Furthermore, in a nod to Kinder’s reputation off the field, his old catcher added, “There’ll be places explored in National League cities this coming season that were never heard of by ballplayers.”

In January 1956, a few months after Ellis Kinder had been sold by the Boston Red Sox to the St. Louis Cardinals after eight years in the Hub, his friends threw him an Appreciation Night at Boston’s Sheraton Plaza Hotel. In attendance were the governor, the mayor, several former teammates, and 600 assorted guests. Birdie Tebbetts, who had caught Kinder in the late 1940s and was then managing the Cincinnati Reds, served as toastmaster. Birdie had caught Hal Newhouser and Dizzy Trout in Detroit, Mel Parnell in Boston, and Bob Lemon, Early Wynn, and a late-career Bob Feller in Cleveland, but he told the gathered throng that he never caught a better pitcher than Kinder. Furthermore, in a nod to Kinder’s reputation off the field, his old catcher added, “There’ll be places explored in National League cities this coming season that were never heard of by ballplayers.”

This was Ellis Kinder: well-loved by teammates and fans, more than a bit reckless off the field, and a great pitcher, one of the best pitchers in Red Sox history, both as a starter and a reliever for eight years. All that, and he didn’t get to the majors until he was 31, or develop into a star until he was 33. “Old Folks” was late to the party, but he sure knew what to do once he got there.

Ellis Raymond Kinder was born on July 26, 1914, in Atkins, Arkansas, about 50 miles northwest of Little Rock. The second son of Ulysses and Iva Kinder — at the time of the 1930 census there were three other sons — his father was a farmer of corn and cotton, struggling to feed and clothe his large family. Ellis was picking cotton in the fields by the time he was 10 years old. Kinder later recalled working 5 1/2 days a week in the fields, then going fishing on Sunday with his mother.

Kinder attended public school through eighth grade. He played baseball occasionally, and was good enough to play on the high school team while still in grade school. He continued to play sandlot ball on the weekends after he had left school behind. On March 28, 1934, still working the fields, the 19-year-old Kinder married Hazel McCabe. Soon after, he began work driving a tractor for a road contractor. By 1937, Kinder’s parents had both died, and Kinder was responsible for his wife and daughter and three siblings.

That summer he was first recruited by Hartel Gilliam, the owner of the Jackson, Tennessee, club in the Class D Kitty League. Kinder turned down the offer of a job because he could not afford to work for $75 a month for four months. With a steady job, extra income from an occasional ballgame, and six dependents, he stayed where he was. In 1938, he turned Jackson down again. In August of that season he went to Jackson during his two-week vacation and pitched three innings for the club, allowing four hits and two runs in a single game.

The next season Ellis’s boss told him he’d hold his job for him if he wanted to join a team for the summer. Reporting to Jackson for full-season duty in 1939, Kinder put up a 17-12 season, with a 3.59 ERA over 223 innings. Despite his success, his advanced age was enough to keep him in the low minors in 1940, when he recorded a 21-9 record, leading the league with a 2.38 ERA, a league-record 307 strikeouts, and 276 innings pitched.

The New York Yankees were sufficiently impressed to purchase his option for $5,000 and assign him to Birmingham of the Southern Association in 1941. After he split six decisions through June, the Yankees released him and he returned to Jackson, where his family now lived. Back home, Kinder recorded an 11-6 record with an impressive 2.88 ERA.

Kinder pitched for Jackson (Mississippi) of the Class B Southeastern League in 1942, finishing 6-2 with a 2.88 ERA (again), then for Memphis in the Southern Association (2-3, 5.52). After the 1942 season he retired from professional baseball, and took a better-paying job back home in Jackson as a pipe-fitter with the Illinois Central Railroad. Kinder had lived in poverty his whole life. He grew up poor, and he was still poor, earning a small wage while supporting a large extended family. As much as he loved baseball, he needed the money.

In 1944 he was offered a contract to return to Memphis by manager Doc Prothro. Prothro was surprised when Kinder turned him down again. “I need pitchers,” claimed Prothro. “The Illinois Central Railroad needs pipe-fitters,” responded Ellis. Two days later, Prothro substantially upped his offer, and Kinder put his uniform back on. It is not known how the Illinois Central Railroad dealt with the loss of their pipe-fitter.

Kinder was the star of the 1944 club, finishing 19-6 with a 2.80 ERA. Memphis lost in the seventh game of the playoff finals to Nashville, with Kinder taking the loss in the final game. The more famous player on the 1944 Memphis Chicks was outfielder Pete Gray, who put up a .333 batting average despite not having a right arm. At the end of the season, the contracts of Gray and Kinder were purchased by the St. Louis Browns, though Gray’s acquisition understandably garnered most of the headlines and press. Though Gray played the 1945 season with the Browns, Kinder did not, instead serving a year in the Navy, being discharged in March 1946.

Kinder finally got to the big leagues with the Browns in 1946, just shy of his 32nd birthday. Fully matured, the right-hander stood 6-feet-1 and weighed 195 pounds, with penetrating blue eyes and sharp facial features that made him look much younger than he was. Mainly a mop-up pitcher as a rookie, Ellis got into 33 games and finished 3-3 with a 3.32 ERA. The following season he joined the starting rotation and began the year with five straight wins, but tailed off to 8-15 and a 4.49 ERA for the lowly Browns. His most famous moment in his rookie season might have been during a game in 1947 when a dead fish, likely dropped by a gull passing overhead, landed on the mound behind him as he prepared to pitch to Bobby Doerr in Fenway Park.

On November 18, 1947, Kinder was traded to the Boston Red Sox, along with infielder Billy Hitchcock, for three players — pitcher Clem Dreisewerd and infielders Sam Dente and Bill Sommers — and $65,000. This deal, along with an even larger one for Vern Stephens and Jack Kramer the day before, made the Red Sox instant favorites for the pennant after their disappointing 1947 season. Newly hired manager Joe McCarthy was ecstatic about the news, telling the press, “Kramer and Kinder are sure to help the pitching situation. [General manager] Joe Cronin has certainly helped a situation that didn’t look too promising.” In January, McCarthy added, “From the reports I’ve heard on Kinder, he may be as important and perhaps help us more than the others. I understand he has great stuff.”

Kinder arrived in Sarasota several days late, with a reputation for enjoying drinking and chasing women, and reportedly did not tend to his training regimen with as much enthusiasm as Joe McCarthy would have liked. After his manager bawled him out in the hotel dining room one morning after a late night on the town, Kinder got with the program a bit more, though his off-field activities did not slow down. McCarthy grew to tolerate Kinder’s lifestyle once he saw that Ellis showed up every day ready to pitch. As teammate Maurice McDermott later recalled, “[McCarthy] never asked Kinder what he’d done the night before. He always knew where Kinder was — in bed with a bottle and a blonde.”

Kinder hurt his arm in New Orleans just before the start of the regular season, and missed a few weeks with his right arm in a cast. He started pitching well in midsummer for the resurgent Red Sox, winning 10 of his 17 decisions over 28 games and 178 innings. After the Red Sox lost the season-ending playoff game to the Indians, Kinder lamented, “If it hadn’t been for my arm trouble, we’d have won this easy. Well, I’ll show them next year. I’ll win 20 games or more for this club and we’ll win the pennant.”

In the spring of 1949, Red Sox catcher Birdie Tebbetts predicted a 20-win season for Kinder, a prognostication that was not taken seriously despite Tebbetts’ closeness to the situation. After all, Kinder was nearing his 35th birthday and had just 21 major league wins under his belt. Kinder had a great spring, and began the season in the starting rotation. Like the rest of the team, Ellis started the season somewhat slowly before kicking it into gear in the early summer. After a loss to the Browns on June 9 dropped his record to 4-4, Kinder embarked on a stretch of pitching that made him the best pitcher in the game. He won six straight games before suffering a loss in relief on July 24. Kinder then won his next 13 starts during the Red Sox’ valiant fight for the pennant. By September McCarthy was even using Kinder in relief between his starts, a season total of 13 appearances out of the bullpen.

The Red Sox finally caught the Yankees on the next-to-last weekend of the season, and the two clubs fittingly were tied going into the final contest at Yankee Stadium on October 2. Kinder, 4-0 against the Bombers and working on a streak of 18 consecutive victories as a starter, got the assignment for the Red Sox against Vic Raschi. Kinder allowed a run in the first inning, then shut the Yankees down, but trailed 1-0 entering the eighth frame. When it was Kinder’s turn to bat, with the club in desperate need of some offense, McCarthy pinch-hit the little-used Tom Wright for his great pitcher. Wright walked, but was retired when Dom DiMaggio hit into a rare double play to end the brief threat. Kinder’s replacements, Mel Parnell (who had pitched the day before) and Tex Hughson, allowed four runs in the bottom of the eighth, and the Red Sox’ subsequent three runs off Raschi in the ninth were not enough. Kinder’s removal in this game was perhaps the signature moment of the season for the Red Sox, and remained a controversial one for decades in Boston. Joe McCarthy, whose moves always seemed to work out when he managed the Yankees, unfortunately found that in Boston his most important decisions, right or wrong, did not pan out. On the train ride back to Boston after this final game, Kinder, apparently quite drunk, sharply criticized his manager, further eroding McCarthy’s reputation in Boston.

After the season Kinder was named the American League pitcher of the year by The Sporting News. There was no Cy Young Award in 1949, but since his award was voted on by the nation’s sportswriters, there is a good chance Kinder would have won the Cy Young Award had there been one. His greatest competition came from his teammate Mel Parnell, who was equally heroic during that season. The 1948 and 1949 clubs are unfortunately remembered for failing to win on the final day of each season, but both teams had to come from behind to force those final games, especially in 1949. This team was 35-36 on July 4, and 61-22 thereafter. Their two ace pitchers were a big reason for the turnaround, Parnell finishing 15-2 after this date, and Kinder 16-2. A couple of extra runs on October 1 in New York and it is not hard to imagine Ellis Kinder as the league’s MVP and the history of the Red Sox forever altered. But those runs were not forthcoming.

During his early years in the majors, Kinder had operated a taxi business back home, often after spending a few weeks barnstorming with fellow major leaguers. After the 1949 season, Kinder first barnstormed with a team run by Dick Sisler, then returned to Jackson, according to the Sporting News, “exercising and working on motor repairing.” He barnstormed again in later years.

After two straight harrowing pennant race losses, Kinder joined a 1950 club again expected to contend. Kinder was beset with a series of injuries that season, breaking a rib shagging flies in the spring, and suffering a bad back in midsummer. Always a quick healer, Ellis started out in the rotation, but was converted to the bullpen in midseason, ending up 14-12 in 48 games, with a 4.26 ERA. Manager Steve O’Neill, who took over for McCarthy in July, liked using Kinder as a bullpen weapon during the pennant race.

One of Ellis’s career highlights took place on August 6, 1950, when he beat the White Sox 9-2. Kinder hit a grand slam off Billy Pierce and drove in six runs in all, a record for AL pitchers at the time. Ellis loved facing the White Sox, as this game came in the middle of a club-record 18 straight victories for Kinder over Chicago, a streak that lasted from 1948 to 1953.

His personal life made the news that offseason. His wife, Hazel, was granted a divorce in court in Jackson on January 11, on a charge of desertion, a charge Ellis did not contest. Mrs. Kinder was granted full custody of their three children: Charles, Jimmy, and Betty. On January 16, Kinder married Ruth Corkery in Boston, after a courtship that was likely longer than the five days he was single. His second marriage, by all accounts, did not slow him down much.

The 36-year-old Kinder was now a full-time relief pitcher, and his career was in some ways just getting started. In 1951 Kinder led the league with 63 games pitched, a team record, finishing 11-2 with a 2.55 ERA. In the middle of a big three-game series in New York in early July, O’Neill could not resist starting Kinder, and Ellis responded with a complete game 10-4 victory, notching 10 strikeouts. On July 12, Kinder entered a tie game in the eighth inning in Chicago, and pitched 10 shutout innings before his club finally pushed across a run in the 17th inning for the win.

Kinder was an early pioneer in the evolution of the ace relief pitcher. Although there were many examples of pitchers who starred in this role for a few years, it was likely the use of Joe Page by the Yankees in 1949 that cemented the belief that having a star in the bullpen had become a necessity for success. The conversion of Kinder, one of the best starters in the game, to a relief pitcher in 1950 was a bellwether moment in the story. By late 1951, O’Neill could say that Kinder was too valuable to start and be taken seriously. Bobby Doerr, nearing the end of his long career with the club, said, “In all the years that I have been with this team, we have never had a relief pitcher like Ellis. The way he can come in and stop a rally or hold a lead is something at which I marvel. He is just as good as Page was for the Yankees two years ago.”

For his efforts, Kinder received two first-place MVP votes in 1951. In January he was honored as the team’s MVP at the annual writers’ dinner in Boston. That offseason, he stayed in Massachusetts, working at a sporting goods store in New Bedford.

In 1952 Kinder worked for another new manager, Lou Boudreau, who had to learn how to use his newfangled pitching weapon. Boudreau chose to use Kinder in both starting and relief roles and, coincidence or not, his star pitcher was soon bothered by a few injuries. A sore back sidelined him briefly in early May, then he hurt himself while breaking up a fight between teammate Jimmy Piersall and New York’s Billy Martin on May 24. He hurt his back again in June and was finally shut down for two months. Between and around the injuries, Kinder finished the 1952 campaign with just a 5-6 record but with a 2.58 ERA in 23 games, including 10 starts.

After the 1952 season, at a party in Siesta Key, Florida, Kinder suffered a wound to his stomach when he either was cut with a knife or fell on a drinking glass. He was taken to the hospital, but refused treatment and walked out. How much the erratic and suddenly fragile 38-year-old had left as a pitcher was certainly in doubt.

Ellis Kinder had a lot left, it turned out. He pitched just one inning in spring training in 1953 due to a prolonged bout of flu, and was used gingerly at the start of the season. He ended up pitching in 69 games, breaking the league record set by Ed Walsh in 1908, winning 10 of 16 decisions, and posting a microscopic 1.85 ERA. He also hit .379 (11 for 29). When manager Boudreau approached the mound to bring in Kinder, he put his hand on his head signifying a crown — for the king of relief pitchers. Bill McKechnie, the longtime major league manager, and at the time the Red Sox pitching coach, commented, “He’s got a heart, a head, and a low sharp breaking slider that’s as tough a pitch to hit as anybody throws.” For the second time in three years, Kinder was named the team’s Most Valuable Player by the local press corps.

In 1954 Kinder hurled 48 games, split his 16 decisions, and posted a 3.62 ERA over 107 innings. He was sidelined with various ailments, including a throat infection early in the year and later pneumonia. On July 15, in a ceremony at home plate, Kinder was made an honorary member of the City of Boston Junior Firefighters.

The following season Kinder turned 41, yet he improved his ERA to 2.84, finishing 5-5 in 43 games. He had become quite famous for his success at such an advanced age, acquiring the nickname “Old Folks.” He attributed his success to pitching every day: batting practice, long toss, or in game action. He caused a bit of a stir when he responded to a question about legalizing the spitball by saying, “Bring it back. I’ve got a dandy one already.”

On June 13, 1955, Kinder was involved in a near-fatal car accident long after curfew. He said he swerved to avoid a dog, and then crashed his vehicle into a telephone pole. When asked what a dog was doing out wandering around at 2:30 in the morning, Kinder only laughed. Typically, he received just a few cuts and bruises and was pitching within a few days. On September 3, Kinder came into a bases-loaded situation in the eighth inning, tossed 4 2/3 scoreless innings, then drove in the winning run in the top of the 12th.

In December Kinder was sold to the St. Louis Cardinals for the waiver price. The Red Sox felt they could make the deal because of the emergence of a few young relievers, including Ike Delock, Leo Kiely, and Tom Hurd. Still, the popular Kinder was caught off-guard. “There is nothing wrong with my arm, and there’s no reason I can’t help the Cardinals next year,” Kinder said. “I’ve enjoyed playing in Boston, where the fans have been wonderful to me. And I must say that Joe McCarthy and Mike Higgins were the best managers I ever played for.”

Ellis Kinder Night was on January 24, when he was lavished with gifts and praise. Jimmie Piersall spoke of the support Kinder had given when he struggled with mental health issues in 1952 (“like a big brother to me”), Governor Christian Herter called him a wonderful example to all ballplayers, and Tebbetts said, “Never in all my baseball career have I ever heard Kinder say anything bad about any player, manager, or umpire.” Kinder received telegrams from Ted Williams, Rocky Marciano, and a poignant one from Mrs. Georgiana Agganis, the mother of Harry Agganis, Ellis’s teammate who had died tragically just months before. Kinder concluded the night by saying, “Baseball’s been very good to me. I’ve had a lot of thrills, and tonight is one of the biggest.”

Kinder starred early for the 1956 Cardinals, causing manager Fred Hutchinson to say, “As far as I’m concerned he’s earned his salary already.” Vinegar Bend Mizell, after winning two games saved by Kinder, said, “If anything happens to him, ah’m gonna pack my bags and go home.” He slumped briefly in June, and despite his 2-0 record and 3.51 ERA was sold to the White Sox on July 11. In Chicago, he pitched well again, finishing 3-1 with a 2.73 ERA in 29 games.

Kinder held out briefly in the spring of 1957, which may have helped speed the end of his career. After just seven innings in spring training due to a leg injury, and one scoreless appearance in April, he drew his release when the White Sox had to reduce their roster to 25 in mid-May. He signed with the San Diego Padres of the Pacific Coast League in June, but pitched just twice. After a few fruitless weeks hoping to find a job, Kinder soon realized his career was over.

The marriage of Kinder and Ruth did not last long, and after his career ended, Ellis moved back to Jackson and soon had moved in with Hazel, his first wife. Kinder worked hard his whole life, and quickly returned to a life of labor. He hired himself out to perform carpentry, roofing and other home-improvement jobs. He struggled to control his life-long battle with alcohol, and his struggle was often in vain.

He was in poor health for a few years before undergoing open-heart surgery, a rare procedure in those days, in the fall of 1968 in a Memphis hospital. While recovering, he watched that year’s World Series between the Tigers and Cardinals, but he suffered a reversal and died on October 16, 1968. The 54-year-old Kinder was laid to rest at Highland Memorial Gardens, in Jackson, Tennessee.

In an article written shortly after Kinder’s death, Harold Kaese recalled the heart and competitiveness of Ellis Kinder. “Tip the lid to Tex Hughson, Dave Ferris, Mel Parnell, and Jim Lonborg, but if the Red Sox had to win one game, my pitcher would have been Kinder,” wrote Kaese. Kinder, like teammate Vern Stephens, who died just 18 days after Ellis, did not live to see his great Red Sox teams from the late 1940s become the stuff of nostalgia. While many of his ex-teammates could make a living in the 1980s and beyond selling autographs and writing books, Ellis Kinder, one of the greatest players on those teams, has faded from memory. No more.

Sources

Roger Birtwell, “Kinder, Ex-Pipe-Fitter, Fits in Well as Bosox’ Sub Starter for Kramer,” The Sporting News, April 27, 1948.

Roger Birtwell, “Story of Kinder, Pitcher Unusual,” Boston Globe, January 24, 1956.

Hy Hurwitz, “Fans, Friends, Players Give Kinder Big Night,” Boston Globe, January 25, 1956.

Harold Kaese, “Vern and Ellis Among Sox Best,” Boston Globe, November 6, 1968.

Gerry Moore, “Kinder to Start, Relieve, Too, He Learns at Dinner,” Boston Herald, January 25, 1956.

Obituary. The Sporting News, November 2, 1968.

Steve O’Leary, “Wonder-Kid Kinder ‘Just Starting’ at 35,” The Sporting News, September 28, 1949.

Milton Richman, “‘Guts of Iron’ Kinder,” Baseball Digest, November 1949.

Maurice Stansell, telephone interview, July 2006.

Full Name

Ellis Raymond Kinder

Born

July 26, 1914 at Atkins, AR (USA)

Died

October 16, 1968 at Jackson, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.