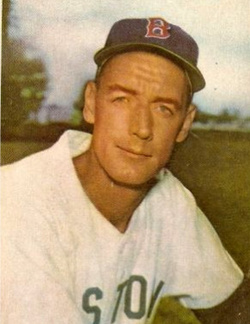

Sid Hudson

When Tom Brokaw wrote about the “greatest generation,” he might have easily selected the life of Sid Hudson as one of its shining examples. Although he was never a baseball great, Hudson’s work in the sport spanned seven decades, stretching from the humble beginnings of Depression-era sandlot ball to the multibillion-dollar game of the present day. Hudson overcame many obstacles along the way, while serving his country in World War II and finishing as a teacher of the game to a new generation of ballplayers.

When Tom Brokaw wrote about the “greatest generation,” he might have easily selected the life of Sid Hudson as one of its shining examples. Although he was never a baseball great, Hudson’s work in the sport spanned seven decades, stretching from the humble beginnings of Depression-era sandlot ball to the multibillion-dollar game of the present day. Hudson overcame many obstacles along the way, while serving his country in World War II and finishing as a teacher of the game to a new generation of ballplayers.

The story of Sidney Charles Hudson began in 1918 – or more precisely, 1915. For many years he listed his date of birth as January 3, 1918, and it was not until the early 1990s that it was corrected in baseball reference guides. Sid remained hazy on this subject, saying he cannot remember exactly when and how it got mixed up. His place of birth also brings some confusion. Early references cite his place of birth as Oliver Springs, Tennessee, while contemporary sources place his first appearance in nearby Coalfield. His father, Henry Hudson, a carpenter, died when Sid was 7 years old. Sid’s mother, Addie, was left with a large family to raise. Sid helped as much as possible, eventually cutting short his schooling in his junior year of high school to work as a clerk in a grocery store. Before then, he had displayed a remarkable athletic talent for his basketball team and as a first baseman on the baseball team.

Hudson still managed to fit sports into his work schedule, playing when he could for several local amateur teams. Eventually he came to play for the East Lake team in the Chattanooga City League. Sid played mostly at first base, with his 6-foot-4 height helping him with tough throws. A decent batter, Hudson later took great pride in his batting during in his major-league career finishing with a .220 career average including several chances as a pinch-hitter. Hudson attracted the attention of Guy Lacy, a former Cleveland Indians player who was now managing Sanford in the Class D Florida State League. Lacy signed Hudson for the 1938 season, and put him at first base, where he got off to a slow start. The team did poorly as well, and Lacy was replaced as manager by Bill Rodgers. A right-handed thrower, Sid had a fastball, hard curve, and, later, a changeup he developed with advice from future Hall of Famer Ted Lyons, who at the time was pitching for the rival Chicago White Sox.

Rodgers had brought another first baseman with him and Hudson had a seat on the bench. A week later, the team was far behind in a game against Palatka. Rodgers asked Hudson if he could go in to pitch a few innings. Sid agreed and struck out the last six batters of the game. He was in the rotation for the rest of the season, winning 11 games for a last-place team and filling in at first base and third base. By the end of the year, Rodgers had turned Sid into his favorite project, working with him daily on pitching and fielding drills.

In 1939, the extra tutelage paid off as Hudson turned in a brilliant season. He won 24 games, with a 1.80 ERA, lost only 4, and completed all 27 of his starts. He continued to play part time in the infield, batting .338. He started four more games in the league playoffs and completed and won them all. His extraordinary season caught the attention of the Washington Senators and Cleveland Indians, each of which tried to sign him for their minor-league teams. Sid chose the Senators, noting that with Mel Harder and Bob Feller on the Cleveland staff, his opportunities would be greater in Washington.

In 1940, Hudson went to spring training in Orlando, Florida, with the Senators, along with his Sanford teammate and fellow 20-game winner Harry Dean. The organization had coach Benny Bengough (the catcher for the 1927 Yankees) work with each of them, and planned to send both to the club’s Charlotte affiliate. Bengough worked closely with Hudson on throwing the curve and changeup, and Sid was surprised to find himself a member of the Senators starting rotation. In just two years, he had gone from the sandlots to the majors.

Hudson started the second game of the season against a very tough Boston Red Sox lineup, featuring four future Hall of Famers, Jimmie Foxx, Joe Cronin, Bobby Doerr, and Ted Williams. The Red Sox prevailed, 7-0, behind a home run by Foxx, but the Washington press lauded the rookie’s poise and character in such a difficult debut assignment. Hudson won two of his next three starts, but then lost seven decisions in a row. Fully expecting to be sent to the minors, he was surprised when he received nothing but encouragement from owner Clark Griffith and coach Bengough. Hudson was told he was overthrowing, and to get back to basics — in Bengough’s words, to “rare back and burn the ball in”.

Taking the mound against St Louis on June 21, 1940, Hudson walked the first three batters, but then went to his fastball and retired the Browns without a run scoring. He then shut them down completely, taking a no-hitter and 1-0 lead into the ninth inning. Although Rip Radcliff spoiled his bid with a double, Hudson won the game and turned his season around. He won his next five games, including a second one-hitter, against Philadelphia on August 6; the no-hit bid was spoiled by Sam Chapman’s seventh-inning single.

On September 2, Hudson faced the Red Sox’ Lefty Grove in what Sid later called one of the highlights of his major-league career. The two battled in a 0-0 duel through 12 innings, with Hudson pitching out of numerous jams, until the Senators broke through and gave him the win in the bottom of the 13th inning. The victory capped a remarkable rookie season. Fresh out of Class D ball, Hudson had won 17 games for a team that won only 64. He threw 19 complete games, three of them shutouts, and won nine one-run decisions. He finished second, by a scant three votes, to Lou Boudreau in the Rookie of the Year voting held by the Chicago baseball writers.

In the next two seasons, Hudson continued to be a pitching mainstay for the Senators. Despite losing records, he was selected to the All-Star team both years. In the 1941 game, he was briefly on the hook for the loss until Ted Williams won the game with a three-run homer in the ninth inning. Hudson was a workhorse for the Senators, completing 17 games in 1941 and 19 in 1942. Although his numbers were respectable (13-14, 3.46 ERA in 1941; 10-17, 4.36 in 1942), the Senators slumped in both seasons. Hudson enjoyed another favored career moment at the end of the 1941 season, when he shut out the Yankees in the last game of the season. Hudson had one of the 13 strikeouts that season of Joe DiMaggio, whom he considered the best all-around player he ever faced.

America was soon in World War II and Hudson spent the next three years in the Army Air Forces, finishing his service time with Special Services on Saipan. In his 38-month tour of duty, Hudson pitched hundreds of innings in service games and also ran calisthenics for cadets five times daily. When he came back to the majors in 1946, his arm was fatigued and he developed a bone spur on his shoulder. Pitching with great pain, he turned in a decent 1946 season (8-11, 3.60 ERA), but as his arm worsened, his record declined along with it. His ERA rose to 5.60 in 1947, although he had one great moment, defeating Spud Chandler and the Yankees, 1-0, on April 27, Babe Ruth Day, when more than 58,000 fans packed Yankee Stadium to honor Ruth, who was suffering from the cancer that would take his life a year later. Hudson had first met Ruth at a benefit game during the war, and remembered feeling sorry that April day to see one of his heroes in such poor health. Matching zeroes with Chandler into the seventh inning, Hudson won his own game by singling and scoring on a base hit by teammate Buddy Lewis. In 1948, he continued to slump, falling to a 4-16 record with a dismal 5.88 ERA with twice as many walks as strikeouts. A worried Hudson went to John Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore to have his arm examined by specialists. He was given a choice: opt for surgery without any guarantees that he would recover fully, or try pitching with a different delivery. Hudson chose the latter, changing to a side-arm style. The transformation paid off slowly – he led the league with 17 losses in a tough-luck 1949 season – but by 1950 he had returned to form, winning 14 of the team’s 67 victories and earning attention as one of the season’s best comeback stories.

In 1951, Sid slid backward with a 5-12 record and a 5.13 ERA, but in 1952, he got off to a strong start with the Senators, completing six of his seven starts with a 2.73 ERA. Seeking pitching help, the Red Sox acquired him in a trade on June 10, 1952, for pitchers Walt Masterson and Randy Gumpert. Although sad to leave Washington, Hudson welcomed a trade to a team with a better lineup, and also noted years later that he enjoyed escaping the humidity of the Washington summers. He went on to win seven and lose nine games for the Red Sox, pitching for manager Lou Boudreau, who had edged him out for the unofficial Rookie of the Year award in 1940. Hudson finished his career in a variety of roles for the Red Sox over the next two seasons. Still relying on his side-arm delivery, he went 6-9 in 1953 as a starter and reliever. His adjusted ERA of 119 (100 is average) was the best of his career.

Sid also enjoyed playing with, Ted Williams, a teammate he greatly admired. On September 17, 1953, Hudson was trailing Ned Garver and the Detroit Tigers 1-0 in the eighth inning at Fenway Park. As Sid recounted years later, Ted told him “he’d hit that little slider into the right-field seats and win the game.” And, just as he had done for him in the 1941 All-Star Game, Williams bailed out Hudson with a dramatic two-run, game-winning home run.

In 1954, now 39 years old and the third oldest player in the league, he worked mostly out of the bullpen, winning three games and saving five. The Red Sox slumped badly that season, with their lowest win total (69) since 1943. Among other changes, after the season Boudreau was replaced as manager by Mike Higgins, and Hudson had thrown his last major-league pitch. He went to spring training with the Red Sox in 1955, but was released before the start of the season. This ended a career in which Sid had often pitched well for below-average teams. He had won 104 games, lost 152, and completed 123 of his 279 major-league starts.

The 1954 season may have been Hudson’s last as an active major-league pitcher, but it was far from the end of his time in major-league baseball. Indeed, his release merely ushered in a new phase of his career. The Red Sox kept Hudson as a scout, a position he held for five years. In 1961, he returned to his baseball roots by accepting a job as a pitching coach for the expansion Washington Senators. Hudson remained in that organization for 25 years, following the team to Texas in 1972. He worked as a pitching coach at both the major- and minor-league levels and served under six different managers, including Gil Hodges, Billy Martin, and his old friend Ted Williams.

In 1964, while working with the Senators’ Geneva farm team in the New York-Penn League, Hudson devised a contraption known as the “gadget.” The device consisted of a leather strap that went around the pitcher’s wrist. Attached to the strap was a strip of elastic with loops for the third finger and thumb. The loops pulled the finger and thumb to the ball and the strap allowed for the arm to stretch straight while throwing but then pulling in at the moment of release. According to Hudson, the gadget got the pitcher used to the feel of throwing a curveball in practice, which then made it more effective in a game.

Hudson had always demonstrated patience in his baseball career, and had valued all the coaching tips given him. Therefore, it was no surprise that he was able to make positive contributions as a coach. Former Senators pitcher Jim Hannan credited Hudson with helping him achieve the three best years of his career, recalling, “He really understood what goes through a pitcher’s mind and how you have to handle pitchers.”

One of his last projects was working with a 39th-round draft choice in 1982. That pitcher, a young left-hander, caught Hudson’s eye because of his loose, live arm. (According to Sid, “There was no substitute for those young, live arms.”) However, when he asked him to throw from the stretch, the prospect replied “What’s that?” Hudson patiently explained it to him. Twelve years later, that pitcher — Kenny Rogers – threw a perfect game for the Rangers as part of a career in which he won more than 200 games and recorded more pickoffs than any other pitcher in history.

After leaving the Rangers organization in 1986, Hudson finished his baseball life by becoming the pitching coach at Baylor University. Sid spent six years there, advising his young pitchers on the nuances of the game, and becoming infamous for his painstakingly long walks to the mound. His pitchers included Scott Ruffcorn, who starred for Baylor and was a No. 1 draft choice for the White Sox in 1991. In 1992, at the age of 77, Hudson finally hung up his spikes for good. His personal connection to the game continued through his grandson Sam Hays, who was drafted by the Seattle Mariners and spent several years in their organization.

Sid spent the final part of his life living in Waco, Texas, fully relishing the memories of his baseball career. He and his wife had raised two daughters. He still received numerous letters from fans young and old, most of them autograph requests that he faithfully answered. Hudson enjoyed sharing stories with visitors, treating them to his “baseball room,” which contained a large collection of memorabilia. In 2008, his beloved wife of 63 years, Marion, died. Sid followed his wife in death just a few months later, succumbing to strokes and melanoma on October 10, 2008, at the age of 93. He had dedicated his life to baseball – and enjoyed every minute of it.

This biography was published in “1972 Texas Rangers: The Team that Couldn’t Hit” (SABR, 2019), edited by Steve West and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Interview with Sid Hudson in 2003, conducted by mail (thanks to Jason for help with this).

Holley, Joe, “Sid Hudson, 93; Pitched For Senators in 1940s,” Washington Post, October 24, 2008.

Shelton, Julie , “Former Major Leaguer Sid Hudson Dies at 93,” (http://www.kwtx.com/blogs/all/30830304.html, October 10, 2008. Shelton is Sid’s granddaughter-in-law.)

Sherrington, Kevin, “A Life Full of Curves,” Dallas Morning News, October 26, 2008.

The contents of Sid Hudson’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, including the following:

Clippings covering Sid Hudson’s playing career, from the Washington Post, Cleveland Plain Dealer, New York Times, and The Sporting News, including articles and columns by Shirley Povich, Robert Ruark, Joe Williams, Bob Considine, and Gordon Cobbledick.

A press release on Sid Hudson from the American League Service Bureau, by Henry P. Edwards, dated January 5, 1941.

Kelley, Brent, “An SCD Interview with Sid Hudson,” Sports Collectors Digest, January 17, 1992.

Richman, Milton. “Comeback of the Year: Sid Hudson,” Baseball Digest, August 1950.

Norman Macht graciously shared his superb draft article and interview with Sid Hudson. Gabriel Schechter and Eric Enders kindly assisted me in acquiring research materials from the Hall of Fame Library. SABR members Rod Nelson, Tom Hufford, and Matthew Bohn all provided help in sorting out the discrepancies between Sid’s “dates” of birth.

As always, www.retrosheet.org and www.baseball-reference.com were indispensable to my research.

Full Name

Sidney Charles Hudson

Born

January 3, 1915 at Coalfield, TN (USA)

Died

October 10, 2008 at Waco, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.