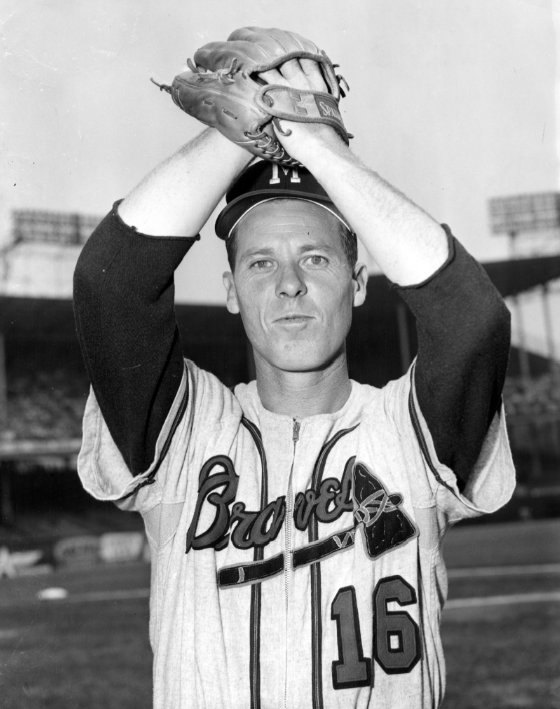

Dave Jolly

Dave Jolly was 28 years old when he made his major-league debut as a member of the Milwaukee Braves. Both he and the team arrived in Milwaukee the same year, 1953. Over the ensuing five seasons the soft-tossing, durable right-handed pitcher became an integral member of the Braves bullpen, throwing 291 innings over that span, winning 16 games and finishing second to Ernie Johnson with 158 relief appearances. By the end of the 1957 season, however, when the Braves won their only World Series for Milwaukee, Jolly’s major-league career was over. After bouncing around for a few years in the minor leagues, he settled down in the small town of his birth to raise his family. Almost ten years to the day after his major-league debut, Jolly died, five months shy of his 39th birthday.

Dave Jolly was 28 years old when he made his major-league debut as a member of the Milwaukee Braves. Both he and the team arrived in Milwaukee the same year, 1953. Over the ensuing five seasons the soft-tossing, durable right-handed pitcher became an integral member of the Braves bullpen, throwing 291 innings over that span, winning 16 games and finishing second to Ernie Johnson with 158 relief appearances. By the end of the 1957 season, however, when the Braves won their only World Series for Milwaukee, Jolly’s major-league career was over. After bouncing around for a few years in the minor leagues, he settled down in the small town of his birth to raise his family. Almost ten years to the day after his major-league debut, Jolly died, five months shy of his 39th birthday.

David Jolly was born in Stony Point, North Carolina, in the northwestern part of the state, on October 14, 1924, the second of five children of Ralph Jolly, a mill worker, and his wife, Minnie. At Stony Point High School, Jolly excelled at baseball and basketball; he played both sports in the local Tri-County League, too. He graduated from high school in the spring of 1942, and on April 30, 1943, Jolly enlisted in the US Army. Eventually sent overseas, Jolly was assigned to the 54th Field Hospital and saw action in France and Germany. He was discharged in December 1945 and at age 22 returned to the US, unsure of his immediate future.[1]

The origins of Jolly’s professional baseball career are unclear. Whether he attended a tryout camp or was scouted around Stony Point is unknown, but in any event, early in 1946 Jolly signed with the St. Louis Browns. The Browns sent him to Mooresville of the Class D North Carolina State League. (Mooresville is 30 miles south of Stony Point.) Joining a pitching staff led by future Hall of Famer Hoyt Wilhelm, Jolly won five games and lost three in 1946, then was 14-7 om 1947 as the Moors captured the league championship. Jolly played first base and the outfield when not pitching, and in the championship season he hit.357 in 155 at-bats, with two home runs. After the season Jolly was drafted by the Cincinnati Reds, based on a recommendation from a scout named Tex Millard.“I was passing through Stony Point one day,” Millard said in 1951, when “I saw a sign which said ‘baseball today’ and decided to take a look. I watched Jolly work and later the Reds signed him.”[2]

The next two seasons in the Reds organization were more challenging for Jolly. In 1948 Cincinnati assigned him to the Tulsa Oilers of the Double-A Texas League. He walked an alarming 40 batters in 59 innings, and the Reds sent him to Class A Columbia (Sally League) where the right-hander fared much better, reducing his walks per nine innings to four. In 1949 he returned to Tulsa and spent the entire season there, but again struggled to harness his control, this time walking more than a batter an inning (222 batters in 202 innings). Control problems aside, Jolly was proving to be an innings-eater.

For 1950 the Reds promoted Jolly to Triple-A Syracuse, where he allowed more hits than innings pitched (162 in 146 innings) and more walks than strikeouts (76 to 74). Despite Jolly’s 5-11 record, Cincinnati invited him to spring training in 1951. In November 1950 Jolly and Doris Hunter were married; they had met while Jolly was playing with Mooresville. They had two sons, Michael and Craig, and after Jolly’s premature death in 1963, mother and sons, as of 2013, continued to reside in Stony Point.

Jolly didn’t stick with the Reds in 1951; on April 1 he was optioned once again to Tulsa, where he spent the entire season. The Reds once again recalled Jolly to report the following season, but on October 17 they released him outright to the Oilers. Then a change in organizations propelled him to the major leagues. In January 1952 the Kansas City Blues, the New York Yankees affiliate in the Triple-A American Association, purchased Jolly’s contract from Tulsa.

The Blues decided Jolly would be a starter. That role lasted for just two games. As Jolly related a year later, “I got a start and lost that. Then I went on relief and won six.”[3] And that was the conversion that sent him to the major leagues. Pitching solely in relief, he finished the season 6-1 with a 3.51 ERA. His 40 appearances were second most on the club. He was now a full-time reliever.

Jolly was particularly effective against the Milwaukee Brewers, who finished in first place, 12 games ahead of the second-place Blues. And after the season the Brewers’ parent club, the Boston Braves, took Jolly in the major-league draft. In February 1953 Jolly went to Bradenton, Florida, for spring training with the Boston Braves. By the time spring training ended, he was a reliever for the Milwaukee Braves. He had grown comfortable coming out of the bullpen rather than starting. Indeed, when asked midway through training camp which he’d rather do, he replied, “I like the bullpen. I like to be on relief.”[4] The press speculated that Jolly was “likely to be in the … Braves bullpen with Bob Buhl and Larry Jester.”[5]

Despite his confidence, there were times during training camp when Jolly worried about making the team. He still had occasional bouts of wildness. During his seven minor-league seasons he’d issued 631 walks, an average of 5.5 per 9 innings, and had never been able to totally conquer his control. Nonetheless, Manager Charlie Grimm showed confidence in him, saying that “Dave showed me he knows how to pitch when he was with Kansas City. There are few relief pitchers with better control when his arm is right.”[6] In the end, Jolly made the team.

At 6 feet tall and 160 pounds, Jolly didn’t possess overpowering stuff; he had a limited repertoire, and relied on guile rather than speed to keep the batters guessing. Asked during spring training about his approach to working the hitters, he said, “I get them out, I hope, with a slider. I haven’t any trick pitch, no knuckler, forkball or fadeaway; just a slider which I try to get over.”[7] He kept the slider low and outside and complemented it with a “sneaky” letter-high, inside fastball. Beyond his pitching smarts, Jolly also possessed another attribute that perfectly suited him for the pressures of relief pitching. Jolly was a quiet, reserved man who rarely displayed emotion or got rattled. He carried that calm demeanor to the mound. (Bullpen mate Ernie Johnson dubbed him Gabby, the converse of his nature, and the nickname stuck.) In assessing his rookie reliever that first spring, Grimm described Jolly as “cold as granite … a cold, calculating guy. He looks and acts like a good relief pitcher. He appears to be the type who would enjoy the afternoons in the bullpen, imagining it was Central Park.”[8] Jolly told a sportswriter the following season, “I can’t afford to get upset when they make an error behind me, or when a dangerous hitter comes to the plate. I just throw the best pitch I have and that’s it. If they hit it, they hit it and if they don’t, they don’t.”[9] His was the perfect temperament for pitching the Braves out of trouble.

He got few of those opportunities in his rookie year. The second-place Braves had seven pitchers who totaled over 100 innings each (plus 81 more thrown by Johnson), and there were only so many innings to go around. Moreover, as Jolly said the next season in looking back on 1953, “There were times last year when I had trouble throwing a ball. I got a sore arm early last spring and it stayed with me most of the year.”[10] In all, he pitched in only 24 games, working just 38? innings and losing his only decision.

Things improved noticeably for Jolly in 1954. As the Braves took a step back in the standings, dropping to third place, Jolly enjoyed the finest season of his career. It didn’t take him long to stake his claim to the top spot in the bullpen. Jolly earned his first major-league win in his second appearance of the year, on April 23, in St. Louis, coming in to pitch in the bottom of the ninth with the teams tied 4-4. Jolly worked five innings, giving up one run and three hits, and gaining the win when the Braves scored two runs in the top of the 14th. It was the first of several extended outings that year. On June 8, at home against the New York Giants, he threw 7? innings, allowing five hits and three runs and striking out a career-high nine batters. On July 9 at Cincinnati, he allowed just one hit in 6? innings. He pitched six innings at Philadelphia on September 13, allowing three hits and two runs, and on the 17th he pitched five innings at St. Louis, giving up no runs and three hits.

Perhaps Jolly’s finest outing of the 1954 season took place on July 17, at home against Brooklyn. On that day he made the only start of his major-league career, and pitched ten innings before being lifted for a pinch-hitter in the bottom of the tenth. Jolly allowed just four hits and one run, although he walked six. In the top of the 11th inning, Lew Burdette surrendered the winning run and took the 2-1 loss.

That season Jolly had added another pitch to his arsenal, a knuckleball. He most likely learned it from Hoyt Wilhelm during those first two seasons in Mooresville. Years later Jolly told a reporter, “I had been practicing with a knuckler for about four or five years but I was always afraid to throw it in a game. Finally, I found nerve enough to use it against the Cardinals early in the 1954 season and I was surprised how effectively it worked. I figured if it worked against a gang of hard hitters like the Cardinals, I’d be able to use it against any club. I gained confidence in the pitch and it became my best one.”[11]

Indeed, just the thought that he might throw the knuckler made Jolly effective. “Actually, I don’t use it much, especially when I’m called on in the middle innings,” he said in July 1954. “For one thing, I’d rather have the batters expect it than get it. For another, I never can be sure what my knuckler will do. Sometimes it just hangs out there, waiting to be hit.”[12]

It wasn’t hit very frequently in 1954. To be sure, Jolly never had another season even close to the one he produced that year. He amassed career highs with 47 appearances, 111? innings pitched. 10 saves, and a record of 11-6. He had a fine 2.43 ERA. At 29 years old, Jolly was at the top of his game.

Jolly was also handy with a bat in his hands. In 48 at-bats during his five major-league seasons, he had 14 hits, for a .292 batting average. On June 27, 1954, in Philadelphia, Jolly relieved Ernie Johnson in the fifth inning with Milwaukee trailing 3-2. Leading off in the top of the seventh, Jolly hit his only major-league home run, off Curt Simmons, to tie the game, making himself the pitcher of record. In the bottom of the inning the Phillies got a run on a hit by Jolly’s mount opponent, Simmons, and Jolly became the losing pitcher.

The remaining three years of Jolly’s major-league career were marked by injuries and ineffectiveness; he never again found the form that made him such a stopper in 1954. In 1955, as the Braves again finished in second place, Jolly appeared in 36 games but was hampered throughout the season by an elbow injury that forced him from a game at Cincinnati on May 30. Afterward the right-hander told the press, “It’s as if you touched me with a lighted cigarette.”[13]

It wasn’t the first time he’d suffered through the pain. “I had a similar injury in 1949 with Tulsa,” he said, “and was out for a month. It’s been bothering me off and on all spring.”[14] X-rays revealed a pulled tendon, and Jolly missed much of the 1955 season, finishing with a poor 5.71 ERA and 51 walks in 58? innings. It was the worst season of his career.

By the spring of 1956 Jolly appeared to be fully recovered. He threw eight hitless innings over his first five regular-season appearances, winning two of the games. Early in the season, however, Fred Haney replaced Grimm as manager and, despite Jolly’s return to health, further work became scarce for the 31-year-old. As Haney increasingly called on younger members of the Braves’ pitching staff, Jolly appeared in just 29 games, pitching only 45? innings. He again battled control problems, issuing 35 walks. Returning to Stony Point for the winter, Jolly had reason to be concerned about his future with the team. As it turned out, the 1957 season would be his last in the major leagues.

For Jolly, the Braves’ championship 1957 season was largely one of inactivity and speculation about his departure. As June approached and he had yet to pitch in a game, Jolly complained that Haney planned to use him only as a “give-up pitcher in big scoring games.” He said, “I don’t know why Fred felt that way and I’ve never asked him for a showdown. … With us, it’s mostly hello and goodbye these days. Right now I’m just waiting around to see what he’s gonna do. … You try not to get down in the dumps, but you can’t help wondering what’s going to happen.”[15]

After a quick start out of the gate (9-1 the first two weeks), with the big-three starters, Spahn, Burdette, and Buhl, eating up innings and limiting chances for relievers, the team began to falter in May, at one point losing seven of 12 games and falling two games behind Cincinnati. Looking for more production at the plate, management scoured the league for trade possibilities, and Jolly’s name was frequently mentioned as a candidate. It was also reported that the Braves had tried to send Jolly to the minors but apparently couldn’t get waivers on him and felt he was worth more than the $10,000 waiver price.[16] It was a frustrating situation for the veteran reliever.

It was not until May 24, at Wrigley Field in Chicago, that Jolly made his first appearance of the season, mopping up in the ninth inning of a 5-1 Milwaukee loss. (Jolly was the last of the Braves’ players from the Opening Day roster to get into a game.) So it went for the right-hander in that championship year. He made what turned out to be his last major-league appearance on September 14, 1957, against the Dodgers at County Stadium , By season’s end he had pitched just 37? innings in 23 games. During Milwaukee’s World Series victory, Jolly never got into a game. On October 15, five days after the World Series ended, the Braves sold his contract to San Francisco in a straight cash deal (no waivers were involved; the purchase price was unclear).

For the next four years, the right-hander hung on in the minor leagues. At spring training with the Giants in 1958, he developed shoulder tendinitis. Unable to pitch, he was returned to the Milwaukee organization at the end of March, and was sold outright to Wichita of the American Association, for which he made 28 starts and had a 10-11 record. From 1959 through 1961 he also made stops at Houston (11-10 in 1959), Buffalo, Vancouver, Mobile and Portsmouth-Norfolk. Hewas invited to spring training with the Cubs in 1960, but failed to make the team. After the 1961 season, he retired as a player.

With his baseball career over, the 37-year-old Jolly settled in Stony Point. During the offseasons he had worked in Statesville, North Carolina, for John Boyle and Company, a manufacturer of awnings and industrial fabrics, and now he returned there full time. He also helped coach Statesville’s Babe Ruth League All-Stars, which compete for the state championship. He taught the junior boys Sunday school class at his church, for which he’d several years earlier bought an organ with his $8,924.36 slice of the World Series winnings. Jolly became just a regular member of the community.

During this second stint in the minor leagues, Jolly had had several seizures. The first had occurred in 1959 when he was with Houston, in the American Association. Jolly spent several days in the hospital undergoing tests, but nothing conclusive was discovered. Since that time there’d been other periodic episodes as well, diagnosed as small seizures, when he seemed to be staring into space. Doctors sent him to the VA Hospital in Durham for tests, yet none were able to provide an answer. Then one day, during an exam with an ophthalmologist in Stony Point, the doctor found pressure on the optic nerve, and suspected the worst. Soon, Jolly was diagnosed with a brain tumor.

In July 1962 he underwent surgery to remove the tumor, and was listed in critical condition. In October Jolly returned to work, but in December he was again hospitalized at the VA Hospital in Durham. He never went home again. After 149 days in the hospital, with Doris at his bedside, Dave Jolly died on May 27, 1963. He was 38 years old. His sons were ages 10 and 7.

At Jolly’s funeral, the Rev. Homer Good, who had been the ballplayer’s pastor at Stony Point Baptist Church, summed up Jolly’s career. “Dave Jolly was one of America’s great athletes,” the pastor said. “He played well the game he loved so much. He played well the Game of Life.”

Jolly was buried at the Stony Point Cemetery. He was the second of the original Milwaukee Braves to pass away, following fellow pitcher Vern Bickford, who had died of cancer in 1960.

One posthumous remembrance of Jolly can be found near his home town. In the 1970s three ballfields were built about four miles outside of town, between Stony Point and Taylorsville. Ernie Johnson was there for the dedication that day as one of them was named after Stony Point’s native son.

This biography is included in the book “Thar’s Joy in Braveland! The 1957 Milwaukee Braves” (SABR, 2014), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. To download the free e-book or purchase the paperback edition, click here.

Sources

Burlington (North Carolina) Daily Times News

Corsicana (Texas) Daily Sun

Coshocton (Ohio) Tribune

Milwaukee Journal

Newark (Ohio) Advocate

Rocky Mount (North Carolina) Evening Telegram

Statesville (North Carolina) Landmark

Statesville Daily Record

Wisconsin Rapids Daily Tribune

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

My sincerest appreciation to SABR member Bill Mortell for genealogical assistance. Telephone conversations with Doris Jolly, Dave’s widow, on August 2 and 24, 2012.Dave Jolly player file from National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

Notes

[1] Jolly’s Army enlistment record indicates that his civil occupation was as a “skilled molder.”

[2] Gastonia Gazette, May 5, 1951.

[3] Unidentified article dated March 14, 1953, in Jolly’s Hall of Fame file.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Undated and unidentified article in Jolly’s Hall of Fame file.

[7] Unidentified article dated March 14, 1953, in Jolly’s Hall of Fame file.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Milwaukee Journal, July 28, 1954.

[10] Undated and unidentified article in Jolly’s Hall of Fame file.

[11] Jolly’s obituary, New York Times, June 8, 1963.

[12] Milwaukee Journal, July 28, 1954.

[13] Wisconsin Rapids Daily Tribune, May 31, 1955.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Associated Press via Janesville Daily Gazette, May 18, 1957.

[16] Ibid.

Full Name

David Jolly

Born

October 14, 1924 at Stony Point, NC (USA)

Died

May 27, 1963 at Durham, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.