Lee Riley

“My dad was dashing,” said Pat Riley, the NBA Hall of Fame coach. “One thing he always did, was he had those wonderful Clark Gable-type suits on, and bright red ties and starched shirts.” He had a lot of style to him.”1

Lee Riley was a slugging outfielder, a “hard guy”2 who toughed out 22 seasons in the minor leagues and belted 234 home runs.3 Riley played for teams in 18 cities trying to achieve the ultimate respectability of being a major leaguer. The closest he came to his dream was to play in just four games, a mere 12 at-bats, with the Philadelphia Phillies in 1944 (He was 1-for-12). He stayed on with the Phillies, managed in their farm system for eight years, and brought his adopted hometown Schenectady, New York, the Blue Jays, its first baseball championship in 1947.

Riley then set his sights on managing or coaching. He thought he had a future in the Phillies organization until they suddenly released him in November 1952 when they reduced their farm teams from 12 to 9.4 Riley was out of baseball at age 44. Could he be persuaded to return later in life?

Leon Francis Riley was born on August 20, 1906, in Princeton, Nebraska, 18 miles from the state capital, Lincoln. His father, Henry Leo Riley, was a bank teller who was born in Illinois and moved to Nebraska with his widowed mother, Bridget, and nine siblings. Riley’s mother, Lizzie (Chamberlain), was born in Michigan. Lee had two brothers: Donald, one year older, and Terrance, seven years younger.

Riley attended Princeton High School for two years before transferring to Cathedral Catholic High in Lincoln, where he starred on the football, basketball, and baseball teams. He graduated in 1924 and entered St. Mary’s College in St. Mary’s, Kansas, where he played on the baseball team coached by Steve O’Rourke, a scout for the Boston Red Sox. O’Rourke was credited with sending at least a half-dozen players to the majors, but there is no record of his ever recommending Riley.

Riley batted left and threw right and was described by a newspaperman thusly: “He is the picture of health with his ruddy complexion and even distribution of 180 pounds over a six-foot frame.”5

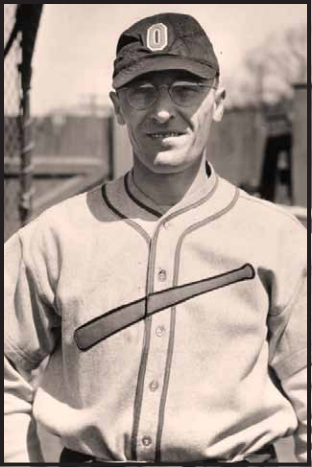

The 21-year-old Riley began his professional baseball career in the summer of 1927 with the Ottumwa (Iowa) Packers in the Class-D Mississippi Valley League. He was quickly promoted to his hometown Class-A Lincoln Links in the Western League. The Links finished in last place (63-90) in 1927 and switched to the Nebraska State League the following season. A new franchise, the Pueblo (Colorado) Steelworkers, took their place, and Riley played for them.

Riley had a breakout season with Pueblo in 1928. He batted .370 and finished fifth in the chase for the league batting title. Pueblo finished in fourth place in at 85-78 thanks to Riley’s hitting. His slugging percentage of .640 included 43 doubles, 17 triples, and 13 home runs. After the season Pueblo’s manager publicly offered Riley to the Philadelphia Athletics on a “make-good basis.” Riley’s photograph appeared in newspapers across the country with a story implying that he had been purchased by the A’s and would report to spring training with them. Within two weeks the A’s replied via American League President Ernest Barnard that they had canceled the deal. Nevertheless, The Sporting News wished young Riley well and predicted that fans would be hearing good things about him one day.6

Riley appeared to be a great hitter but how were the other aspects of his game? “Fans expected to see him conked on the bean by a fly ball any time one was hit to his territory. In the winter he worked with a friend on his fielding shagging flies. By 1931 he was making great catches and doing it with finesse. He overcame a weakness that had him blackballed.”7 Riley’s fielding improved – at least to the point where he was considered by the press to be an adequate outfielder.

Riley spent three more seasons with Pueblo and put up good numbers, averaging 173 hits per year and a .319 batting average. When the Pueblo team went bust after the 1931 season, Riley was purchased conditionally by Galveston. During spring training he was released and was claimed by Omaha of the Western League. In 73 games for Omaha, he hit .391. This caught the attention of the St. Louis Cardinals, who purchased Riley’s contract and sent him to the Rochester Red Wings of the International League, where he hit .276 in 76 games. As one sportswriter stated coldly, “Riley was a great stickman with Omaha in the old Western league. He went up to the International League in 1932, but it was a case of: I’ll be right home, ma; they started to curve them today.”8

The Red Wings featured two great right-handed-hitting outfielders roughly the same age as the left-handed-hitting Riley: George Puccinelli, who batted .391 with 28 home runs and had a 31-game hitting streak, and Ray Pepper, who boasted a .298 batting average with 14 triples and 9 home runs. With the friendly right-field fence in Silver Stadium just 315 feet away one wonders why Riley didn’t hit more than five home runs. Perhaps, as the newspaper story suggested, Riley couldn’t hit curveballs. The Cardinals seemed disappointed with Riley and dropped him down to the Houston Buffaloes in the Class-A Texas League but they already had two left-handed-hitting starting outfielders so Riley was shipped to the Elmira Red Wings in the New York-Pennsylvania League for 1933. He started off slowly there too, but just as he began to hit well he injured his shoulder in July while “making a remarkable running catch.”9 Riley didn’t fare so well there either, hitting just .254 for the season. This was the worst time for Riley not to perform his best. Was it vision problems? We do see him wearing eyeglasses in photos in later years. Was he playing hurt? There was the pulled muscle in his shoulder. Riley played center field that year and injuries limited him to 128 games.

Lee met his future wife, Mary Rosalia Balloga, in Pueblo in 1928 while she was working as a waitress at the Bluebird Diner. They were married in 1931. The first of their six children, Leon Francis Jr., also be nicknamed Lee, was born in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1932. Leonard was born in Lincoln, Nebraska, in 1934, Dennis M. and Elizabeth, in Davenport, Iowa, a few years later, and Patrick J. and Mary Kathleen in New York state in 1945 and 1947, respectively. The Rileys’ first daughter died in infancy from a rare skin condition in an Omaha hospital in December 1934.

Lee Riley made sure his family was an athletic one. If he thought any of his children had an iota of athletic ability, he pushed them. Lee Jr. played seven years in the NFL and AFL as a defensive back and kick/punt returner. Lennie played college basketball until he injured a knee, and Pat was a standout in almost any sport he tried. Lee Sr. made sure that Pat played against older, bigger kids to toughen him up. But he rarely, if ever, showed up at his children’s school games – that was up to them, though he may have watched them from a distance.

Mary Kay was an excellent bowler as was Liz, also a gymnast. Dennis never went out for organized sports.

In 1934 Elmira traded Riley to the Huntington (West Virginia) Red Birds of the Middle Atlantic League, where he hit .260 in 18 games. Soon he was released by the Cardinals and found himself back in the Class-A Western League, with the Davenport Blue Sox. He spent the next three years playing for the Blue Sox, who won three straight pennants. Riley hit .270, .320, and .299 respectively. In 1936, Riley’s final season in Davenport, he finished fourth in the balloting for MVP. The franchise became a Brooklyn Dodgers affiliate.

The Beatrice Blues had finished near the bottom of the Class-D Nebraska State League three seasons in a row and wanted to turn their franchise around. In 1937 the Brooklyn Dodgers affiliate selected Riley to be player-manager. Riley played in 114 games and hit .372 with 14 home runs. He returned in 1938, and hit .365.

The Blues folded and Riley’s player contract was purchased by Knoxville of the Southern Association for 1939. He played for three teams that year: In 20 games for Knoxville he hit .353, in 23 games for Elmira he hit .274, and in 38 games for Baltimore in the International League, he hit .212.

In 1940 Riley signed on as player-manager for the Oneonta Indians in the Class-C Canadian-American League and hit .340 in 116 games. The Indians finished in fifth place (62-63). In 1941 at Rome, also in the Can-Am League, he hit .391 in 120 games and led the league with 32 home runs. He placed third in league MVP voting.10 In 1942 Riley hit .315 in 61 games for Doc Prothro’s Memphis Chickasaws. His hot bat early in the season kept them in the fight before they fell to fifth place at 72-80. On May 21 Riley hit three successive home runs and a single as the Chicks beat Atlanta, 10-2. He was among five players involved in an altercation and fined after a June 10 game with Little Rock. The following month Riley was playing for the Wilmington Blue Rocks in the Interstate League. He missed time with the club to return home when son Lee Jr. suffered a head injury. Riley batted just .204 in 71 games for Wilmington.

In 1943 Wilmington sold Riley’s contract to the Utica Braves, but Riley declined to report. He worked in a defense plant, Revere Copper & Brass, in Rome, New York, instead, and played on the company baseball team in the Rome Industrial League.11

In 1944, at the age of 37, Riley got his chance to play in the major leagues with the Philadelphia Phillies. The Phillies had a good outfield consisting of Ron Northey, Buster Adams, and Jimmy Wasdell, but with four-year veteran outfielder Coaker Triplett holding out and so many other players in military service, the Phillies’ new general manager, Herb, Pennock wanted to add a fifth outfielder who could hit with power and Lee Riley fit the bill. Also, Riley’s best position was left field so he could sub for regular left fielder Wasdell, who had little power. In short, Riley seemed to complement the crew of outfielders the Phillies had.

Riley made his debut on the second day of the season, April 19, 1944, in Philadelphia before just 2,578 fans. The Shibe Park crowd size approximated a Western League or Nebraska State League game Riley was used to. Riley was called upon to pinch-hit in the bottom of the ninth inning with the Dodgers leading, 4-2, a man on first base, and no outs. Forty-year-old right-handed pitcher Curt Davis, who’d been an All-Star in 1936, was on the mound; Riley flied out to center field. The Phillies rallied to tie the score but went on to lose in the 10th inning, 5-4, on Paul Waner’s RBI single. Waner had turned 41 three days earlier.

Riley started his first game in left field on April 28 at Shibe Park against the Boston Braves and curveballing right-hander Nate Andrews. He batted sixth in the order and went 0-for-5. The Phillies lost, 2-1.

On April 30, in the 10th inning of the first game of a doubleheader against the Braves, Riley was sent in to replace Wasdell, who had been ejected for arguing a called third strike. Riley went hitless in two at-bats. He lined out to right field for his only major-league RBI, which tied the game, 1-1, and grounded out in the 13th inning against right-handed pitcher Al Javery. The Phillies won in 14 innings, 2-1.

Riley started the second game of the doubleheader and got his only major-league hit his first time up. He doubled to center field against right-hander Ira Hutchinson and scored. The game ended in a 2-2 tie due to the Sunday curfew law in effect in Philadelphia.

Two days later Riley was sent down to Utica. There he batted in the cleanup spot for the Blue Sox and manager Eddie Sawyer and compiled a .256 batting average. His 117 bases on balls led the league.

In 1945 Riley returned to a playing manager role for the Bradford (Pennsylvania) Blue Wings in the Class-D PONY League. He tied for the league lead with Carl Sawatski, his catcher, with 13 home runs. Riley walked 121 times, proving that he was still a feared hitter. He came back in 1946 but cut his playing time to 182 at-bats and hit .269 with 4 home runs. He was now 39 years old.

In 1947 Riley led the Schenectady Blue Jays to the Canadian-American League title. He batted just 70 times and hit .257. Tommy Lasorda was a 20-year-old pitcher when he played for Riley in Schenectady in 1948. Lasorda said of Lee’s son, “I used to hold Pat in my lap. Every time I see him now, I think of his father. He looked just like Pat does now. He combed his hair straight back too. He was a tough guy.” Lasorda claimed that Riley once told him the following before removing him from a game: “Know why I couldn’t hit in the major leagues? Because I couldn’t hit left-handed pitchers. If you’d been there, I would have been a star.”12

In 1949 Riley managed Terre Haute of the Three-I League (69-56). His two at-bats were the last in his professional career. In 1950 he managed the Utica Blue Sox to a 64-73 record. In 1951 he managed the Schenectady Blue Jays of the Eastern League to a 73-66 record and in 1952 he managed the Wilmington Blue Rocks of the Interstate League (72-66). On October 22, 1952, the Phillies announced they were trimming their farm system from 12 teams to 9. Riley lost his job. Pat Riley said that upon learning the Phillies had let him go, he went up to the attic and discarded all of his memorabilia.13 He was out of baseball at the age of 44.

Riley then leased the General Electric Athletic Association cafeteria and managed it until 1957. After that he opened Lee Riley’s variety store in Scotia, New York. The store sold gum, cigarettes, and notions, and hundreds of newspapers on Sundays. The lesson that Pat Riley said he learned from his parents was “Live to work. Work to live. My father had to grind it out for six kids. … So, we had the roof over our heads, we had food on the table, and we had hand-me-downs from one another. As soon as I was able to grind it out they got me to grind it out too. Everybody became very independent in the Riley household because we all knew how to work. We watched our parents work, every day. We’d get up at 6 a.m. … open up Lee Riley’s variety store, or when he ran the General Electric Athletic Association, he would open it up, I’d go over and help him. All the kids had to go over sometime during the day and help him.”14

“When Pat became a star basketball player at the University of Kentucky in the mid-1960s, Lee followed his career closely, even though he was 800 miles away and didn’t have the time or money to travel and see his son play. “So my dad used to take his car, his Dodge, and in the winter, he would drive up to the highest hill in [Schenectady’s] Central Park and somehow he could get on the radio WHAS in Louisville and listen to [Wildcats play-by-play announcer] Cawood Ledford. He’d take a six-pack with him and his Camels and whatever Mom made for a sandwich and he’d go up there.”15

In the 1960s the store closed and Riley began to drink. He battled through this and friends helped him get a job as a maintenance man (Lee used the term “janitor”) at Bishop Gibbons High School. After two years he was asked to coach the school’s baseball team. He agreed on the condition that he wear his janitor’s clothes.16 He wanted to teach the kids and for that matter the world a point, and it was that he was the same man whether he wore janitor’s garb with his name patch sewn on it or fancy baseball pinstripes – he deserved the same respect. Every June Notre-Dame/Bishop Gibbons High School in Schenectady presents the Lee Riley Award to the male senior athlete who has shown sportsmanship and dedication to athletic excellence.

Lee Riley died from heart disease on September 13, 1970, in Schenectady, New York, at the age of 64. He is buried in Most Holy Redeemer Cemetery, Niskayuna, New York. His wife, Mary, died on April 21, 2006, at the age of 96.17

This biography originally appeared in “Who’s on First: Replacement Players in World War II” (SABR, 2015), edited by Marc Z. Aaron and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Ira Winderman, “A Job Well Done,” South Florida Sun Sentinel, September 5, 2008, accessed July 5, 2014, at https://articles.latimes.com/2008/sep/05/sports/sp-fame5/2.

2 Tommy Lasorda quoted in Lisa Bowman, “Lasorda Takes a Good Hit,” Dodgers Magazine, n.d., reprinted in Los Angeles Times, July 13, 1988.

3 Riley hit 248 career home runs, according to Baseball America‘s Minor League Register.

4 “Phils Cut Down on Farms, Sever Four Working Pacts,” The Sporting News, November 5, 1952, 6.

5 Francis E. Regan, “Sports Views and Reviews,” Rome (New York) Daily Sentinel, November 28, 1953, 21.

6 Ed Orazeal, “Young Slugger Moves Up,” The Sporting News, November 8, 1928, 2.

7 “Hard Work Brought Riley Up the Ladder,” Ogdensburg (New York) Journal, May 17, 1940, 28.

8 Whitney Martin, “Young Yankees Aped DiMaggio’s Plate Stance,” Associated Press, April 8, 1940, 57.

9 Elmira (New York) Star Gazette, July 12, and July 20, 1933, 10.

10 Rome Daily Sentinel, January 22, 1942, 7.

11 “Revere and Air Depot Clash Sunday for League Flag,” Rome Daily Sentinel, August 14, 1943, 7.

12 Lisa Bowman, “Lasorda Takes a Good Hit.”

13 Mark Kriegel, “The Father Within Pat’s Dad Is Here and Now,” New York Daily News, September 5, 1995, 27.

14 Ira Winderman, “A Job Well Done.”

15 Ira Winderman, “A Job Well Done.”

16 David Halberstam, “Character Study: Pat Riley,” Everything They Had, Sports Writing from David Halberstam, (New York: Hyperion, 2002). Originally appeared in New York Magazine, December 21, 1992.

17 Mary R. Riley obituary, Times-Union, Albany, New York, Accessed on Times-Union.com, March 10, 2014.

Full Name

Leon Francis Riley

Born

August 20, 1906 at Princeton, NE (USA)

Died

September 13, 1970 at Schenectady, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.