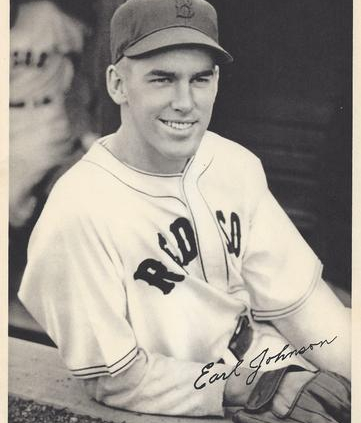

Earl Johnson

Among all the ballplayers who served in World War II, Earl Johnson was the real military hero. Unlike some, he had his better years after the long layoff for the war, peaking in 1947, but began to lose his edge just as the Red Sox entered two seasons (1948 and 1949) when one more win would have made all the difference.

Among all the ballplayers who served in World War II, Earl Johnson was the real military hero. Unlike some, he had his better years after the long layoff for the war, peaking in 1947, but began to lose his edge just as the Red Sox entered two seasons (1948 and 1949) when one more win would have made all the difference.

The “smiling Swedish southpaw” (a phrase found by Jack Kavanagh) was born in Redmond, Washington on April 2, 1919. But he wasn’t Swedish. In fact, his grandfather Hjalmar Johansen was one of the most famous polar explorers from Norway who sought the North Pole with Fridtjof Nansen on the boat Fram. Nansen and Johansen became icebound and had to take dogsleds to survive; they returned a year later and folks thought they were dead. Their return created a major sensation; they became national heroes. Later, Johansen joined in an expedition with Raoul Amundsen to seek the South Pole. An Oslo museum has preserved the Fram for today’s visitors. The family name Johansen was Anglicized to Johnson after arriving in America. Earl was the third of three sons born to George Johansen (who emigrated to the United States from Narvik) and Love Lillian Glass, originally from Canada. The three boys — George, Chet, and Earl — some 16 years later had a sister, Norma Jean. Love Lillian was a homemaker, but worked for a while for Seattle’s Bemis Bag Co. George Sr. played some semipro ball at first base before taking up his life’s work.

“Papa George” Johnson worked as an installer for the Pacific Northwest Telephone Company for 35 years, explains his daughter-in-law Elsie J. Busch, herself of Swedish origin. Elsie’s husband George Jr. was the eldest of the three boys, born in 1914. George Jr. played baseball from grade school on, and for all four years at Seattle’s Ballard High School but graduated in 1933 during the depths of the Depression and earning an income was of immediate necessity. He did play some semipro ball in California, also at first base, but was able to secure a position as lineman with the telephone company. After he and Elsie Granstrom had their first child, George Jr. was able to transfer to inside wiring work working as a PBX installer and no longer needed to climb poles. The couple raised a daughter, Diane, and a son, David. Elsie worked 28 years for an insurance company.

The middle boy Chester was born 16 months before Earl, and had a long career in baseball, ultimately making the major leagues only very briefly near the end of 1946 with the St. Louis Browns. Chet was a left-handed pitcher, like his younger brother, and also played at Ballard High. After graduation in 1935, he worked in the shipyards and attended the University of Washington before finally being scouted and signed by Red Killefer. He began with El Paso in 1939 and played for Tacoma and Bakersfield, as well as three Pacific Coast League teams: San Francisco, San Diego, and Seattle before World War II was over. His brief stay with the Browns only saw him pitch 18 innings in five games, with a 5.00 ERA. He spent 1947-49 with Toledo and Indianapolis in the American Association and then played 1950 through 1956 back in the Coast League with San Francisco and Oakland, and the last five seasons with Sacramento. He won 204 games and lost 215.

Chet was also known for his comical pitching antics in games that were lopsided affairs. “I loved to see the fans have a good time. My purpose, though, was to make the hitters laugh with me or get so mad that they’d lose their concentration and swing at anything I threw.” After baseball, he worked for Seattle Fuel, and later became a salesman for Cudahy Bar-S Meats until his retirement. He also refereed college basketball and football games, and worked with Earl as a pitching instructor at a summer baseball camp in Oliver, British Columbia. Chet and his wife Nancy Lee Rowe had two boys, Bill and Dick — both of whom played ball quite a bit but never to the point of becoming professional — and two daughters, Martha and Theresa.

Earl Douglas Johnson also attended Ballard High. Though in grade school he’d only played softball, he played exceptionally well in high school and was fortunate in being able to receive a baseball scholarship to attend St. Mary’s College in Oakland, California, the college that produced so many major league ballplayers over the years. Pitching at such a showcase school, and at one point winning a reported 24 games in a row, it was no surprise that he caught the attention of scouts from several teams. Earl also played a little semipro ball in Bremerton, Washington in 1939. Red Sox scouts Billy Disch and Ernie Johnson (no relation) are credited with his signing around Christmas time 1939.

He was an imposing 6’ 3”, 200-pounder. Earl was assigned to Boston’s Class-B Piedmont League affiliate in Rocky Mount NC and pitched very well, with a 12-6 record and a 2.67 ERA. He got off to a great start, but Bob Considine wrote that Johnson “was beaten six straight times, trying to win his thirteenth victory for Rocky Mount, and when Heinie Manush, his manager, came up to him one night and said ‘looks like you’ll never win another in this league, kid,’ Johnson thought he was through. But Manush added, ‘So the Sox just phoned me to send you to Boston — so you can win there.’”1

Though still just 21 years old, Earl got a quick promotion to the major league ballclub, simply because (in the words of the Washington Post’s Shirley Povich) manager Joe Cronin “doesn’t know where his next winning pitcher is coming from and can blame his club’s failure to be in the league lead on the worst pitching in the circuit.” By season’s end, no starter had won more than 12 games and the staff ERA was a high 4.89. Yawkey spent some considerable sums trying to buy good pitching, but Povich wrote, “The best young pitcher to come up with the Red Sox in several years is no fancy-priced minor leaguer, but Rookie Earl Johnson, the left-hander Boston signed fresh out of St. Mary’s College in California.”

The young lefty’s major league debut came at Fenway Park in the midst of an eight-game losing streak on July 20, 1940 in relief of Lefty Grove. The Red Sox scored once in the bottom of the first but the veteran Grove was unable to retire a Cleveland batter in the top of the second; he left the game having surrendered four runs. Earl Johnson came on in relief and threw five scoreless innings before the Indians got to him for three runs to break a 4-4 tie. The final score was 9-6 Cleveland. Johnson had walked three and allowed five hits in the six full innings he pitched. He appeared in relief again, and earned his first start in the July 28 doubleheader, beating the St. Louis Browns, 3-1. He walked one and gave up four hits in five innings, relieved by Emerson Dickman.

In his third start, against the Yankees in Boston, Johnson was hit hard off the shin by a batted ball during the first inning and had to leave after completing the inning. The bruise healed quickly enough that he was brought back in the first game of the next day’s doubleheader, throwing three innings in relief and getting the win. Three days later, on August 10, he threw his first shutout, scattering eight hits in 8 1/3 innings before Jack Wilson came on to retire the last two Senators. Povich praised Johnson, as “a loose-jointed blond kid who vaulted into the majors this season.” Only two Senators had reached third base — though Johnson did have to work his way out of a seventh-inning situation which saw the bases loaded and nobody out. His “out pitch” was a “wide-sweeping curve” that he threw to good effect. He got the Senators again, with a five-hit 4-2 win eight days later, sandwiched around a loss to New York. Johnson won a 6-1 four-hitter in Cleveland in mid-September. By season’s end, Johnson had a 6-2 record with a 4.09 ERA. Looking ahead to 1941 spring training, Jack Malaney wrote in The Sporting News that Johnson “finished the American League season in brilliant style.”

With Mickey Harris and Johnson on the Red Sox, Cronin felt free to let Fritz Ostermeuller go. At the end of March, the Sox traveled to Havana for a series of four games, the first against a team of Cuban all-stars and the other three against the Cincinnati Reds. Johnson pitched the first game against the Reds, allowing just four hits in six innings. When May rolled around, he began to hit his stride once more and was pitching well when he came down with a sore arm. He only started once in June, and only lasted three-plus innings. By early July, The Sporting News observed, “Johnson very definitely is on the shelf, and there is no telling when he can get off.” Doctors diagnosed an unusual cause: “He has bad teeth, which were found to be bad, extracted, and they even dug into his jawbone. When the Sox left home last week, he was left behind in the care of the club physician.”

In late August, the same periodical noted that he’d last pitched well on Decoration Day (now Memorial Day); the soreness in his arm had gone away, but he’d been unable to regain his control since rejoining the rotation on the 10th. Johnson’s totals at the end of his first full year in the majors were just 4-5, with a 4.52 ERA. Little did he know that he would miss four full seasons to service in the United States Army. He drew a high number in the draft lottery, and even before Pearl Harbor prompted the massive expansion of the American armed services, he knew the Army was in his future. He was inducted at Seattle on January 5, 1942, and sent a terse telegram to Sox GM Eddie Collins: “Inducted into Army today. Best regards.” Private Johnson was posted to Camp Roberts, California and had made corporal by the summertime — and was pitching well for the Camp Roberts baseball team. For 1942, he was on the National Defense List with the Red Sox, a status he maintained for four full years — more than most ballplayers. And unlike most ballplayers, after going through training, Earl Johnson saw combat duty.

While still in training, he married Jean Taintor in 1943.

Johnson served in the Army, as did Paul Campbell, Tommy Carey, Joe Dobson, Bobby Doerr, Danny Doyle, Dave Ferriss, Al Flair, Any Gilbert, Mickey Harris, Tex Hughson, Roy Partee, Jim Tabor and Hal Wagner. Partee took part in the invasion of The Philippines.

Sgt. Earl Johnson served with the 120th infantry (30th Division) and landed in Europe 21 days after D-Day. “We were a replacement unit,” he told the Providence Journal’s Bill Parrillo. “We had to go through Omaha Beach to get there….The wreckage was still there, the burned-out tanks and half-sunken ships and assault boats that were just so much twisted steel.” Several times, he came across groups of dead bodies — from both sides — still unburied. He was a rifle platoon sergeant, involved in liberating many towns in France and Belgium. Unfortunately, he witnessed the results of the Malmedy Massacre in Belgium, where 150 American prisoners had been killed by Nazis. Johnson fought in five major conflicts and took part (as did later Sox manager Ralph Houk) in the famous Battle of the Bulge. For heroism in combat, Johnson was awarded the Bronze Star, a Bronze Star with clusters, and the Silver Star, and received battlefield commissions promoting him to lieutenant.

Johnson’s citation for the Bronze Star reads: “On September 30, 1944, in Germany, during heavy concentration of hostile fire, a friendly truck was struck by an enemy shell and had to be abandoned. The fact that the vehicle contained vital radio equipment made it imperative that it be recovered before falling into enemy hands. Sergeant Earl Johnson and several other members of his unit were assigned to this hazardous mission. They courageously braved a severe hostile fire and were completely successful in dragging the vehicle over an area in plain view of the enemy.” The Bronze Star with clusters was awarded after he helped urge a tank crew to drive through a minefield on its way to wiping out a German position which had pinned down his men.

“Lefty” Johnson’s Silver Star required another soldier to pitch in relief of the Red Sox southpaw. The two were fighting hedgerow by hedgerow in France when they noticed a German tank laying in ambush — with its hatch open. Johnson threw two hand grenades at the tank — but missed with both. The other soldier — who’d supposedly never thrown a baseball in his life — tossed one and scored a direct hit. “Gee,” Johnson remarked later, “If I only had that kid’s control, what a pitcher I would be.” The blast killed all five German tankers. Johnson’s platoon started the Battle of the Bulge with 36 men, but ended with only 11.

With the war over in 1945, Lt. Johnson was demobilized and joined many other Red Sox veterans coming back for another year of baseball. In Earl’s case, he’d missed four full years — more than anyone else on the Bosox. Unlike many others, he’d not been playing service baseball; he said he hadn’t touched a ball the whole time. Cronin pinned his pitching hopes largely on the returning Tex Hughson, sophomore Dave Ferriss, and Mickey Harris. Jim Bagby looked promising. Of both Bill Butland and Earl Johnson, Jack Hand wrote in the Washington Post late in spring training, both had been “slow rounding into shape because of their war experiences.” Earl told Bill Parrillo that his fastball was gone: “I had to learn how to become a pitcher instead of just a thrower. I developed a slow curve and a changeup and a slider. That first year, they put me in the bullpen; they didn’t like the fact that I couldn’t throw hard anymore.”

Johnson got into it early, and after Ferriss got battered around in the second start of the season, Johnson came on and three 5 1/3 innings of relief, allowing just three hits, and got the win. The “blond southpaw hurler” (Associated Press) won the May 21 game by throwing five full innings of hitless relief and doubling in the winning runs in the eighth inning. Though he started five games during the year, he was primarily used in relief and all five of his wins came as a reliever. Earl finished the season 5-4, with a 3.71 ERA in 80 innings of work.

Preparing for the World Series, as they waited for the National League’s scheduled three-game playoff to resolve the pennant, Johnson started a “warm-up” game to keep the Red Sox in playing shape, as the Sox played against a team of American League All-Stars. Bill Zuber and Jim Bagby each pitched three innings, too, and the Red Sox won, 4-1. His relief pitching had been “strong” early in the season, but had “tapered off alarmingly in the last two months,” wrote Arthur Daley of The New York Times. But Johnson picked up an important tip during the tune-up games, Daley reported, when Hank Greenberg “sidled up” to him on the bench. “Earl,” Greenberg confided, “There’s something I have to tell you now that you’re about to go into the World Series. For the past two months you’ve been telegraphing every pitch you’ve thrown and the boys in our league have been teeing off on you.” Greenberg explained what Johnson had been doing wrong.

During the 1946 World Series, Earl pitched a hitless ninth and tenth innings in Game One and got the win. In Game Six, he allowed the final run of the game pitching to the Cardinals in the eighth inning, but the Red Sox only scored once and lost, 4-1. After Slaughter had scored to put the Cardinals ahead to stay in Game Seven’s eighth inning, Johnson — who probably should have been pitching instead of Klinger — was brought on and got the final out. When he was due up with two outs in the top of the ninth, Cronin had Tom McBride bat for him and McBride grounded into a force play to end the game, and the Series. Johnson was a lifetime .187 hitter with 13 RBIs in 171 career at-bats.

Earl’s brother Chet was about a year and a half older, and also a left-handed pitcher. He made the majors with the St. Louis Browns and appeared in five games during September 1946. He got three starts but no decisions. Though the two were on opposite benches during two games, they never faced each other. Earl started the September 19 game, but Chet’s second start came two days later against the White Sox. Chet’s major league career ended after his start in the final game of the year. Earl went on and had his best year in 1947. His first start of ’47 came on July 12, against Greenberg’s former team, shutting out Detroit, 2-0, on six hits, while going 3-for-3 at the plate.

His next start came on July 19, and in the bottom of the first inning, Johnson surrendered three consecutive singles. The bases were loaded with nobody out. Johnson got out of it, and never allowed another hit for the rest of the game, the only Browns baserunner coming on his one walk. The final was 1-0, Red Sox. Johnson was involved in three more 1-0 games in 1947, and he started every one of them. He lost a two-hitter to the Senators on August 6, 1-0, on an unearned run. Allowing just three singles (“two of them scratchy affairs”), Johnson turned the tables on Washington with a 1-0 win. Then the Yankees got a superior effort out of Bobo Newsom, who held the Sox scoreless and Johnny Lindell hit a walk-off single in the bottom of the ninth for a 1-0 Yankees win on August 16.

Johnson won his 10th game on September 6, a 4-3 win over the Athletics. A week later, on the day that Red Sox veteran and paraplegic war hero Sy Rosenthal was honored with a “Day” at Fenway Park, there was stiff competition between two pitchers who had both seen combat and Johnson beat Bob Feller with a four-hitter, 3-2. Earl finished 1947 with a 12-11 record and a 2.97 ERA, having thrown 142 1/3 innings in 45 games, 17 of which were starts.

In 1948, Johnson was used almost exclusively in relief, though he had one start in April and two in May. Appearing in 35 games overall, he posted a 10-4 record, but with a distinctly higher ERA at 4.53. He’d begun to lose effectiveness. In 1949, he appeared in 19 games with a 3-6 record and a 7.48 ERA. In 1950, he got into just 11 games, was 0-0 and had an earned run average of 7.24. On July 5, Earl was given his outright release to Louisville — though the A.P. reported that he would remain on the Red Sox roster for 12 more days so that he would become a 10-year man and thus eligible for his pension. Boston called up pitchers Willard Nixon and Dick Littlefield.

The Tigers took a chance on Johnson, signing him on November 15, 1950. He pitched just 5 2/3 innings for them in 1951, in six games, with no decisions and with a 6.35 ERA. His last major league game was on June 3, 1951. With two outs in the top of the ninth inning, Johnson was asked to get the third out, but walked one batter and was touched up for two hits, then removed. The Tigers released him on June 15.

Johnson signed with the Seattle Rainiers to play in the Pacific Coast League. He finished out the ’51 season with as 8-3 record (3.43 ERA) in 17 games, seven of them complete games. His last year as a player came in 1952, finishing his career with Seattle working as a reliever; he was 0-2 with a 4.70 ERA.

Earl is listed as a Red Sox scout in the team’s 1953 spring training guide starting that year, and served as a fulltime West Coast scout for Boston until he retired following the 1985 season. At one point, while working with the Red Sox in March 1965, he also served as a pitching coach for the Mexico City Red Devils.

Earl and Jean had two children, Sally and Earl Jr. Neither showed particular interest in baseball. Sally worked in a restaurant in Iowa and Earl Jr. remains self-employed as a general contractor.

When he wasn’t following baseball in the Seattle area, Earl looked after the laundromat he owned in Ballard. Earl’s sister-in-law Elsie Busch recalls all the trouble it gave him at first. “He used to have all these machines and they were spending all their time on repairing them, until he finally took them all out and put in Maytags. It was just like an advertisement. Put in Maytag and you won’t have to call the repairman.” There were 10 or more machines in the laundromat and he owned it until his death. Earl suffered a minor stroke in the early 1990s and died in Seattle on December 3, 1994. His wife Jean survived him until her death in July 2006.

Thanks to Elsie J. Busch and Dick Bresciani for assistance in putting together this biography.

Note

This biography originally appeared in the book Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948, edited by Bill Nowlin and published by Rounder Books in 2008.

Notes

1. Washington Post, March 23, 1941

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Earl Douglas Johnson

Born

April 2, 1919 at Redmond, WA (USA)

Died

December 3, 1994 at Seattle, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.