John Antonelli

John Lawrence Antonelli, Jr.1 was a Memphis native who carved out a full life in baseball despite a series of setbacks, detours, and U-turns. A high-school pitching phenom, he suffered an elbow injury that forced him to become a full-time infielder, where he played for over 1,700 minor-league games. He then fought his way to the major leagues, played a full season, and then was sent back to the minors for good amid the flood of GIs returning from World War II. He was a player-manager at 19, shifted his sights to the field, and then returned to the dugout — twice. He left baseball to support his family, then after 19 years, returned to the game for a second career almost as successful as the first. Through it all, John maintained strong ties to his hometown.

John Lawrence Antonelli, Jr.1 was a Memphis native who carved out a full life in baseball despite a series of setbacks, detours, and U-turns. A high-school pitching phenom, he suffered an elbow injury that forced him to become a full-time infielder, where he played for over 1,700 minor-league games. He then fought his way to the major leagues, played a full season, and then was sent back to the minors for good amid the flood of GIs returning from World War II. He was a player-manager at 19, shifted his sights to the field, and then returned to the dugout — twice. He left baseball to support his family, then after 19 years, returned to the game for a second career almost as successful as the first. Through it all, John maintained strong ties to his hometown.

Antonelli was born on July 15, 1915 in Memphis, Tennessee, to John Antonelli, Sr. and Vivian (Solari) Antonelli. John Sr. ran the Faust Cafe and was a New York native whose parents had emigrated from Italy. Vivian was a Memphis native and daughter of a local grocer. John and Vivian subsequently had two daughters, Vivian, who died in infancy, and Genevieve, who went on to become a physical-education teacher.2

John Jr. was a right-handed batter who stood around 5 feet 10 inches and weighed 165 pounds. His talent was evident from an early age. As a pitcher and roving fielder at the Catholic High School in Memphis, he helped lead his team to four city titles in five years. During the summers he played American Legion ball, where his pitching talent was similarly instrumental in his teams’ successes in local and regional tournaments.3 After completing high school in 1934, Antonelli got his first taste of the life of a baseball vagabond in semipro ball in Louisiana.4 Shortly into his tenure, he injured his pitching arm. “I was really something,” Antonelli later recalled. “I was a pitcher and I tore a nerve in my arm. So I became an infielder-outfielder.”5

He returned to Memphis and in 1935 and signed with the local Chicks of the Southern Association when their third baseman went down with an injury.6 Asked by a reporter if he had gotten a bonus, Antonelli replied, “I don’t think anybody had ever heard of anything like that. Maybe I got a baseball.”7 Again, though, his tenure was short; after three games at Memphis he was released when the injured player returned; he managed only two hits in 11 at-bats. From there he found his way to Lexington (Tennessee) of the Kitty League, where he was asked to play shortstop as well as pilot the team — at the age of 19. Antonelli proved he was up to the task of managing older players, guiding his team to a first-half title while hitting .325 and playing nearly every position.8 The team was known in the press as “Antonelli’s Giants” (despite having no affiliation with the National League Giants.)9 The team’s second half was not as successful, ending with a 19-27 record for a last-place finish.

Antonelli returned to Lexington the following season but handed over the managerial reins to Rip Fanning. In July he was batting .369 and leading the voting for the league’s all-star team, when he was injured in an outfield collision with a teammate.10 Meanwhile, Fanning was having a rough go of it, with the team finishing fourth in the first half. Fanning was let go, and Antonelli replaced him upon returning from his injury.11 He piloted the club to a second-place finish in the second half, missing the title by two games. He also maintained his hitting prowess, finishing the year with a .363 average.

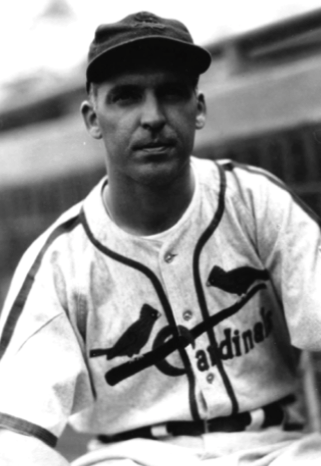

Antonelli’s performance sparked the interest of the St. Louis Cardinals, who bought his contract in 1937 to serve as player-manager of Union City, the Cardinals’ Kitty League entry.12 Antonelli played in 109 games, batting .298 and earning his second straight postseason all-star selection. He also led the club to a league-best 73-46 record. The next spring he was training with Union City alongside the Houston club, a Cardinals A1 affiliate. His play there caught the eye of Houston’s management, who worked out a deal to bring him on as a utility infielder in exchange for pitcher Ed Hurley and outfielder Walter Schuerbaum.13 Houston already had a player-manager, so John would have to temporarily put his managerial aspirations aside. He played in Houston for four seasons, putting up generally solid but unspectacular offensive numbers. He led the league in double plays in 1939 and his versatility made him popular with the fans, who rewarded him with two all-star selections plus one near-miss.

It was during his time in Houston that Antonelli married Amelia Gandi. They had a lot in common; Amelia was also a Memphis native and the child of Italian immigrants, including a father who ran a restaurant. Together they started a family, which included daughters Barbara and Joan. Their timing was fortuitous. With war already under way in Europe, the United States started a peacetime draft in 1940. However, men with families to support were largely exempt from induction. The draft was expanded after the attack on Pearl Harbor, but the deferments for men supporting families remained for much of the war. With the pool of available ballplayers shrinking due to both the draft and voluntary enlistments, John’s value as a ballplayer went up. Not only was there less competition for each roster spot, but also any team signing him could rest assured that he wouldn’t be called away in the middle of the season for military duty.14

Antonelli’s draft status proved to be an advantage in early 1942, when St. Louis’s Double-A club in Columbus traded Morris “Buck” Jones, a single, draft-eligible outfielder, to Houston for Antonelli and first baseman Jack Angle, who was also married.15 John mainly played second and third base at Columbus, and in both 1942 and 1943 he played well enough to keep his job but not well enough to earn a promotion. In 1944, however, he raised his batting average and slugging percentage, earning himself an All-Star selection and a September call-up to St. Louis, where he saw limited playing time. He did not make the World Series roster.

Antonelli stuck with the Cards, making the team in the spring of 1945, but saw action only twice in the season’s first month. Then in May, St. Louis sent Antonelli and outfielder Glenn Crawford to the Philadelphia Phillies for outfielder Buster Adams. It was quite a change, moving from defending World Series champs to perennial cellar dwellers. The Phillies were so bad that in the spring of 1945 three minor leaguers refused to report when Philadelphia bought their contracts.16 For John, though, the Phillies offered regular playing time (125 games over five months), something he was unable to get in St. Louis. His main contributions were strong defense and versatility — he played every infield position. His best performance at the plate came on June 17. Playing both ends of a doubleheader in New York that day, Antonelli punched out six singles in ten at-bats and drove in three runs.

Antonelli joined the Phillies for spring training in Florida in 1946. However, camp was swelled with players returning from the war. With so many players to evaluate, Antonelli got little playing time. When the team broke camp to start the season, it became clear that the there was no place for him on the major-league roster. However, Bucky Harris, who managed the Phillies in 1943, was then the general manager of the International League club in Buffalo, and he was looking for a hard-hitting outfielder and an infielder. So the Phillies sold Antonelli and outfielder Coaker Triplett to Harris’s club in a five-figure cash deal.17

Antonelli’s major-league tenure — eight games in one season and 127 in another — was highly unusual. In fact, since 1900, only one other player has played at least 125 games in a season and recorded so few other appearances: Jim Doyle, who played seven games for Cincinnati in 1910 and 130 for the Cubs in 1911. Hughie Miller, who made it into a single game with the Phillies in 1911 and then 132 games with the 1914 St. Louis Terriers of the Federal League and another seven games with the same team in 1915, had a similar career profile, but no one else is really comparable.18

In Buffalo in 1946, Antonelli saw less playing time than in any other year in his career to that point. Three games into the next season, he was sent to Baltimore, where his playing time and production rebounded. That fall, Antonelli managed the US team in an Inter-American tournament at Caracas, Venezuela.19 He was moved to Double-A Oklahoma City in early 1948, but rather than return to the Texas League, he bought out his contract to return to his hometown Memphis Chicks (now affiliated with the Chicago White Sox.20 On July 9 of that year, Antonelli contributed a single and triple as the Chicks started a game against Nashville with nine straight hits. He ended the year batting. 329 with 32 doubles and 78 RBIs. The next season, though, his production again declined, due in part to injuries, and in November 1949 he was named player-manager of Hot Springs in the Class C Cotton States League. Unlike his first stint as player-manager, this time the 34-year-old Antonelli was the elder statesman, piloting a group of 20-somethings, none older than 26. He made it into only 20 games as a player, but managed his team to a 77-60 record and a postseason title.

As 1951 dawned, Antonelli was offered a chance to move up the ranks as a manager. At the same time, he was offered a full-time sales position with a wholesale liquor distributor. With a young family, John made the choice many players have made before and since, and chose the year-round job in his hometown. He told a reporter at the time: “It’s tough traveling in the lower minors. … I’ve lived more than six months away from home, excepting my two years with the Chicks.”21 Although he kept his hand in with some scouting for the White Sox and conversations with former teammates, Antonelli was largely out of baseball.

While most ballplayers’ stories end there, Antonelli still had a few chapters left to write. The Chicks folded in 1960, but baseball returned in 1968 when the New York Mets moved a Double-A team from Florida to become the Memphis Blues. Will Carruthers, Memphis’s general manager and Antonelli’s high-school baseball coach, was not happy with the team’s performance during that first season. As part of his effort to bring in new blood, he asked Antonelli to come back as a coach. John agreed, starting out coaching first base at home games.22 After his first game, Antonelli said, “It was the first time I had been in a baseball uniform in 19 years. Everything felt kind of funny. But after I got on the field, everything began to fall into place.”23 In the middle of the season, the team’s manager was fired and his replacement was unable to join the club immediately. John managed the Blues during this gap, leading them to a 6-2 record. Later that season his former Catholic High teammates and friends held a commemorative day in his honor prior to a game.

After the end of that 1969 season, the Mets approached John about returning to full-time managerial duties. His daughters had grown up and struck out on their own. But that was not the only factor in his decision. “Working with those kids as a coach really did it,” he told a reporter. “I really love to work with the young ball players.”24 When the Mets formally offered him the Blues’ managerial job for 1970, he accepted.

Antonelli managed in Memphis for three seasons and demonstrated that he still had the ability to get the best from his players, finishing with winning records in two of those seasons. As a manager he was known for his good rapport with his players. In one often-told anecdote, when the Mets called up outfielder Dave Schneck from Memphis, John packed Schneck’s bags and had them ready to go before he delivered the good news back at the team hotel.25 He was also community-minded, initiating the practice of soliciting donations to charity for each of the team’s victories. Even though Antonelli was generally soft-spoken, during games he was not afraid to put on a little show for the fans. “When he’d get to battling an umpire really good, we’d move the ball bag over so he could do his thing,” one of his former batboys told a reporter. “When he’d get thrown out, he’d come over and grab that bag and sling baseballs all over the field.”26

The Mets took notice of Antonelli’s skills. In 1971 they invited him to become an instructor in the Florida Instructional League. In November 1972 Hank Bauer, who had managed the Mets team at Triple-A Tidewater, resigned and the Mets promoted Antonelli to replace him. While his first season resulted in the now-familiar winning record, the 1974 Tides fell to a 57-82 mark. The next year the Mets moved Antonelli back to Double-A and their team in Jackson, Mississippi. There he led his charges to two nearly identical records (65-65 in 1975 and 69-66 in 1976). Then following the 1976 campaign, the Mets hired Bob Wellman, a successful manager from the Phillies system, to take over at Jackson. “I hate to leave Jackson,” John said at the time, “but at my age the day-to-day grind of managing was getting a little tough.”27 Antonelli was kept on as an infield instructor, a job he held until his health began to fail in 1989. He also served as a scout and minor-league coach during that period, with stops in Tidewater, Lynchburg, Little Falls, Columbia, and Kingsport. Soon after the 1990 season began, John died at his Memphis home.28

When he returned to baseball full time in 1970, Antonelli told a reporter, “Sure, I’d like to be a big-league manager. I don’t think I’m too old. I’ve got a lot of good years and this is my career now. I’d like to go all the way to the top.”29 John didn’t make it back to the majors, but plenty of players whose careers he helped would probably consider him tops.

Notes

1 John L. Antonelli the infielder is not to be confused with the pitcher Johnny A. Antonelli, who played more than a decade in the major leagues. Johnny’s biography is part of SABR’s BioProject: sabr.org/bioproj/person/e1774181.

2 Family information is generally based on US Census returns and Memphis City Directories.

3 David Bloom, “A Johnny Antonelli Day and a Lot of Days Past.” Memphis Commercial Appeal, August 12, 1969; Will Carruthers, “Johnny Antonelli Going Up Slowly — But Surely,” Memphis Press-Scimitar, February 12, 1940; Will Carruthers, “Antonelli Hangs Up Baseball Togs,” Memphis Press-Scimitar, February 19, 1951.

4 Will Carruthers, “ ‘Jinx’ Again Lays Heavy Hand on John Antonelli,” Memphis Press-Scimitar, July 27, 1936.

5 Woodrow Paige, Jr., “Antonelli Upped Average Without Swinging a Bat,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, February 15, 1970.

6 Carruthers (1936).

7 Bloom.

8 Carruthers (1936).

9 Richard Worth, Baseball Team Names: A Worldwide Dictionary, 1869-2011 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co, 2013), 161.

10 Carruthers (1936).

11 The Sporting News, August 20, 1936, 12.

12 Richard S. Cox, “Antonelli, Veteran Pilot at 22, New Manager at Union City,” The Sporting News, April 22, 1937, 6.

13 The Sporting News, April 7, 1938, 8.

14 For further discussion of draft deferments and professional baseball during the World War II era, see David Finoli, For the Good of the Country: World War II Baseball in the Major and Minor Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2002).

15 Bob Hooey, “Birds Give Up Bachelor for Two Married Men,” The Sporting News, February 26, 1942, 2.

16 Stan Baumgartner, “Mother Ailing, Caulfield Stays With Oakland,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 11, 1945. See also James D. Szalontai, Teenager on First, Geezer at Bat, 4-F on Deck: Major League Baseball in 1945 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009) for a discussion of the state of the major leagues in 1945.

17 Art Morrow, “Phillies Sell Two, Show Direction of Baseball Winds,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 19, 1946; Cy Kritzer, “Bisons Name Kretlow to Pitch Int, Opener in His 1st Pro Start,” Buffalo Evening News April 17, 1946; Cy Kritzer, “Baseball Bisons Buy Triplett and Antonelli From Phillies,” Buffalo Evening News, April 18, 1946.

18 Author’s analysis of major-league appearance statistics since 1900.

19 “Revolution Greets U.S. Team,” The Sporting News, October 1, 1947, 37.

20 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, March 10, 1948, 28.

21 Carruthers (1951).

22 Bobby Hall, “Blues Spice the Home Dish — John Antonelli Will Coach,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, March 15, 1969, 21.

23 Bill E. Burk, “New Memphis Manager Ends Self-Exile,” The Sporting News, February 7, 1970, 46.

24 Paige.

25 Murray Chass, “Schneck’s Met Debut Like a Movie,” New York Times, July 16, 1972, S2.

26 Bobby Hall, “Friends Remember Antonelli’s Antics,” Commercial Appeal, April 20, 1990.

27 “New Job For Antonelli,” The Sporting News, October 30, 1976, 29.

28 Obituary, The Sporting News, June 4, 1990, 62.

29 Paige.

Full Name

John Lawrence Antonelli

Born

July 15, 1915 at Memphis, TN (USA)

Died

April 18, 1990 at Memphis, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.