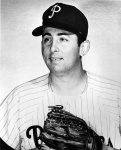

John Boozer

For the 1968 season, the major leagues sought to strictly enforce a rule prohibiting a pitcher from going to his mouth while on the mound. An especially unusual application of the rule took place at Shea Stadium in New York on May 2. Philadelphia Phillies reliever John Boozer entered a game against the New York Mets in the bottom of the seventh inning and went to his mouth before making one of his warm-up pitches.

For the 1968 season, the major leagues sought to strictly enforce a rule prohibiting a pitcher from going to his mouth while on the mound. An especially unusual application of the rule took place at Shea Stadium in New York on May 2. Philadelphia Phillies reliever John Boozer entered a game against the New York Mets in the bottom of the seventh inning and went to his mouth before making one of his warm-up pitches.

“Ball one,” home-plate umpire Ed Vargo exclaimed.

Phillies manager Gene Mauch rushed out to his pitcher’s defense. “What if he does it again?” Mauch inquired.

“I’ll call ball two,” Vargo answered.

“Do it,” Mauch commanded his charge.

Boozer dutifully went to his mouth again, and Vargo called another ball. Mauch instructed Boozer to go to his mouth again, and Vargo called ball three and ejected Boozer and Mauch from the game. Boozer had not even completed his warm-up pitches, much less faced a batter. The rest of the game went off without incident, and the next day National League President Warren Giles decreed that the rule prohibiting a pitcher from going to his mouth on the mound did not apply to warm-up pitches.1 This bizarre incident could not have happened to a more appropriate candidate than Boozer, a genuine eccentric who seemed to revel in his own quirks.

John Morgan Boozer, who spent the second half of the 1964 season working out of the Phillies’ bullpen, was born on July 6, 1938, in Columbia, South Carolina, to John G. Boozer, Jr. and Zela Caughman Boozer. John grew up with his parents and his brother, Thomas, in and around Columbia in an area known as Caughmanville, a community primarily made up of the Caughman family and those who married into it.

Enrolling at Wofford College in Spartanburg, South Carolina, Boozer led the baseball team with 90 strikeouts during his freshman campaign, 1957. After lettering again as a sophomore in 1958, the right-hander, deemed “a touch wild but fast” in a scouting report,2 signed a professional contract with scout A.C. Swails of Philadelphia Phillies in early July.

The 6-foot-3-inch, 205-pound 19-year-old reported to the Brunswick Phillies of the Class D Georgia-Florida League, where he went 3-4 with a 3.67 earned-run average in eight appearances, including five starts. In 1959 he was assigned to another Class D team, the Tampa Tarpons of the Florida State League. Taking the mound as a starter, Boozer posted a 12-15 record with a 3.33 ERA and led the team in starts (27) and innings pitched (208). A highlight for him came in late July when he shut out Palatka 1-0, and drove in the game’s only run.

Boozer went 15-9 for Des Moines of the Class B Three-I League in 1960, and then 1961 turned out to be his best season in professional baseball, 19-9 with a 2.61 ERA for Double-A Chattanooga. He pitched four shutouts in a seven-game win streak that earned him selection to the Southern Association All-Star Game.3 Boozer led Chattanooga in wins and innings pitched (207) as the Lookouts won the pennant (there were no playoffs). He was named the Southern Association’s Rookie of the Year, and was considered a prized prospect in the Philadelphia organization.4 He would never play another game below the Triple-A level.

This is not to say that once Boozer reached the Phillies in 1962 he would be there to stay. Throughout the rest of his career, which lasted until 1969, Boozer split time between Philadelphia and the minors, though he spent all of 1965 in Triple-A and all of 1968 with the Phillies.

In 1962 Boozer went to spring training with the Phillies for the first time. He did not make the club out of camp, and was assigned to Triple-A Buffalo, where he was 8-6. Called up in July, Boozer made his major-league debut on the 22nd, pitching three innings of one-run relief against the visiting Milwaukee Braves. Boozer made eight more appearances for the Phils in 1962 without a decision, and posted a 5.75 ERA.

After the 1962 season Boozer played winter ball in Puerto Rico for the Arecibo club. He earned a spot in the “Gleam Game,” an all-star game pitting imports against natives of Puerto Rico. Boozer struck out four in the final two innings to preserve a 4-1 victory for the imports. He spent most of the 1963 season with the Phillies, with six appearances for the Triple-A Arkansas Travelers (Little Rock). In mid-June, two days after pitching 5? innings in his third start of the season, Boozer made his first relief appearance of 1963 and recorded his first major-league save by throwing 2? innings of scoreless ball to close out the Cardinals in St. Louis. A month later, on July 18, he got his first major-league victory, a 5-1 three-hitter over the Houston Colt .45’s. He finished the season 3-4 with the one save, and posted a career-best ERA of 2.93.

Boozer went to big-league camp again in 1964, but stood in a long line of contenders for jobs on the pitching staff. He told an interviewer, “I’m not going to let it bother me. Except at night when I won’t sleep.”5 He wound up back at Little Rock, and early in the season he was offered as part of a package to the New York Mets in exchange for pitcher Al Jackson and outfielder Frank Thomas.6 The Mets declined that deal but they traded Thomas to the Phillies later in the season for pitcher Gary Kroll and infielder Wayne Graham.

After pitching briefly for the Phillies, Boozer was sent back to Little Rock but was recalled to start the second game of a doubleheader against Cincinnati on July 19. He won, allowing two earned runs in eight innings. Boozer made two more starts the rest of the season, appearing mostly in middle and short relief. He finished the season with a 5.07 ERA. He made four pitching appearances during the Phillies’ epic ten-game losing streak that cost the team the National League pennant. Boozer was the losing pitcher in game five of the losing streak, a 12-inning 7-5 loss to the Milwaukee Braves.

Boozer spent all of 1965 in the minors (9-13, 3.97 ERA for Arkansas), and he made only two big-league appearances in 1966 while going 4-9, 5.40 at San Diego, to which the Arkansas franchise had been moved.

The Phillies had hoped that Boozer, who had won 46 games in his last three seasons in the minors before his big-league debut, would become a major asset to their pitching staff, but it never happened. The big Southerner often seemed content just to be in the majors.7 As he progressed through his 20s, Boozer developed more of a reputation as a flake than as a reliable pitcher. His eccentricities reached far beyond normal baseball tricks such as chewing tobacco and throwing a spitball, both of which he was well known for.

A former teammate, Dick Hall, recalled that Boozer was “a real pen character. … He would bite grasshoppers in half, stick the back half under his tongue and let them hop out of his mouth. And he would eat moths and all kinds of insects. He was always spitting tobacco on the bullpen ceiling. He’d do lovely things. Boozer had a habit of wiping the rubber off with his fingers to get it clean, and then would go to his mouth to clean his fingers.”8

Baseball funnyman Bob Uecker, a teammate of Boozer’s for two years in the 1960s, remembered, “Anything you’d put up, he’d eat it. He’d pick up stuff and eat it. He liked to do it in front of people. It made them sick but it was a big kick for John.”9 Sparky Lyle recalled that Boozer would often spit out a big wad of tobacco and try to catch it in his mouth. Lyle also noted that Boozer would usually miss.10

Sent back to San Diego for the 1967 season, Boozer pitched well, posting a 2.59 ERA in nine starts by the end of May. Desperate for pitching help with newcomer Pedro Ramos and veteran Chris Short on the disabled list, the Phillies brought Boozer back from San Diego on May 31.

His first four appearances didn’t exactly inspire confidence. He started the first game of a doubleheader against the Chicago Cubs on June 6 and was knocked out in the third inning. He came back in relief in the second game and walked the only two batters he faced. He gave up seven runs in four innings of relief three days later against the Pirates, and then, in an appearance against the Atlanta Braves, both batters he faced reached base and scored. Through these four appearances Boozer had pitched six innings, allowed 18 hits and five walks, and owned a lusty 18.00 ERA.

Boozer’s season turned around, however. On June 25 Gene Mauch took a chance on him, pinch-hitting for starting pitcher Dick Ellsworth after three innings in a game against St. Louis. Boozer responded to his manager’s confidence by pitching six innings of one-run relief, striking out seven, and getting the victory, his first major-league win since August 15, 1964. Including the June 25 victory, Boozer went 5-4 with one save and a 2.88 ERA over the rest of the season. Much of his renaissance was due to the work of Larry Shepard, the Phillies pitching coach. Shepard, later the pitching coach for the Big Red Machine teams in Cincinnati, changed Boozer’s fastball grip to create more movement, and worked to change speeds on his curveball. Perhaps more importantly, Shepard urged Boozer to quit trying to be a clown and focus more on baseball.11

The renewed focus on baseball earned Boozer a role on the big-league club for the entire 1968 season, the only season of Boozer’s career in which he did not spend time in the minors. He made 38 appearances for the Phillies, all in relief, posting a 2-2 record with five saves and a 3.67 ERA. Invited to spring training as a nonroster invitee in 1969, Boozer spent April and May at Eugene, his fourth Triple-A club in the Phillies organization. He made his first appearance for the Phillies on June 1, and made 45 more, 44 in relief, before retiring at the end of the season at the age of 30.

With a degree from the University of South Carolina paid for out of his Phillies signing bonus, Boozer returned home to the Caughmanville area and became Lexington County’s first recreation director. He spent the next 15 years developing playgrounds and playing fields for the county.12 Diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease in the early 1980s, Boozer continued to work at the development of the recreation system until late 1985, when his illness worsened. He died at the age of 47 on January 24, 1986, in Lexington. He was survived by his mother, brother, wife Ann, and sons Ian and Curt. He was buried at Pilgrim Lutheran Church Cemetery in Lexington.13 A recreation center in progress at the time of Boozer’s death was named in his honor.14

This biography is included in the book “The Year of the Blue Snow: The 1964 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2013), edited by Mel Marmer and Bill Nowlin. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Notes

1 Baseball Digest, December 1968.

2 Philadelphia Inquirer, January 25, 1986.

3 The Sporting News, July 19, 1961.

4 The Sporting News, July 15, 1967.

5 Philadelphia Inquirer, January 25, 1986.

6 William A. Cook, The Summer of ’64; A Pennant Lost (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2002), 16.

7 John P. Rossi, The 1964 Phillies, The Story of Baseball’s Most Memorable Collapse (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co.), 2005), 92.

8 Bob Cairns, Pen Men (New York: St. Martin Press, 1993), 150.

9 Ibid., 230.

10 Sparky Lyle and David Fisher, The Year I Owned the Yankees: A Baseball Fantasy (New York: Bantam Books, 1990), 119.

11 The Sporting News, July 15, 1967.

12 Philadelphia Inquirer, January 25, 1986.

13 Ibid.

14 The Sporting News, February 17, 1986.

Full Name

John Morgan Boozer

Born

July 6, 1938 at Columbia, SC (USA)

Died

January 24, 1986 at Lexington, SC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.