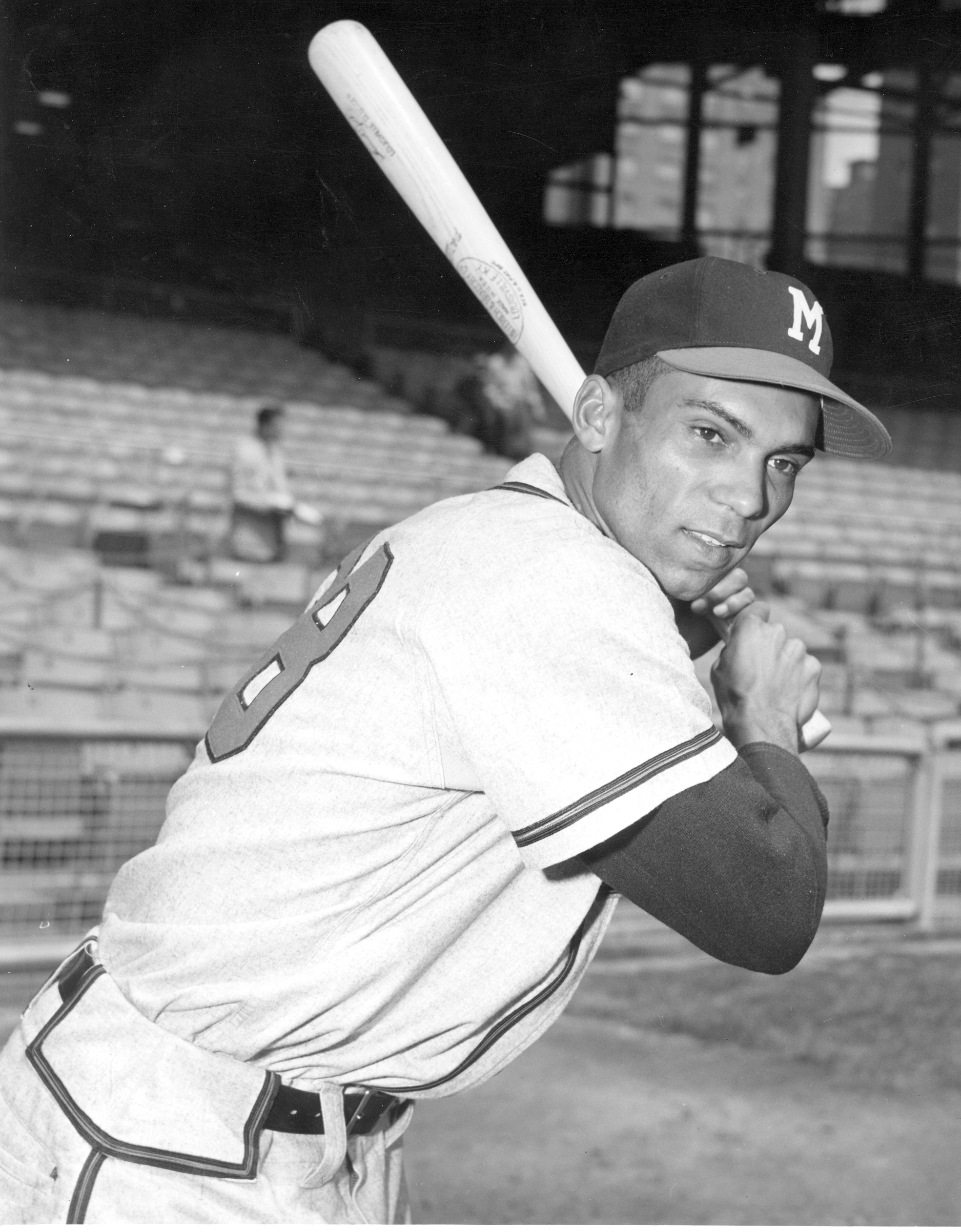

Bill Bruton

Blessed with speed and quickness, Bill Bruton was arguably the fastest man in professional baseball in the 1950s. While prowling center field, he could race back for well-hit long balls and charge in to scoop up potential Texas Leaguers. When batting, he used his speed to intimidate opponents into making throwing and fielding mistakes. He added the important element of speed to the powerful Milwaukee Braves teams of the 1950s.[1]

Blessed with speed and quickness, Bill Bruton was arguably the fastest man in professional baseball in the 1950s. While prowling center field, he could race back for well-hit long balls and charge in to scoop up potential Texas Leaguers. When batting, he used his speed to intimidate opponents into making throwing and fielding mistakes. He added the important element of speed to the powerful Milwaukee Braves teams of the 1950s.[1]

In addition to his speed, Bruton’s development as a player benefited directly from the professional baseball help and advice he received from his father-in-law, Hall of Famer William Julius “Judy” Johnson. Johnson spent 18 years in the Negro Leagues playing third base primarily with the Hilldale Club of Philadelphia and the Pittsburgh Crawfords.[2]

Quiet, thoughtful, and articulate, Bruton also played an important role in sustaining baseball’s initial racial integration progress. Anchored by his religious beliefs, he understood that by becoming a successful professional baseball player he could serve as an important role model for youth as well as grow the popularity of professional baseball. Teammate Hank Aaron once characterized Bruton as “like a father to everyone. (He) really saw what needed to be done. … Just keep playing baseball and the system would change.”[3]

Bruton played for 12 years (1953-1964) in the major leagues for the Milwaukee Braves (eight seasons) and the Detroit Tigers (four seasons). With the Braves he played on two National League champions and in one World Series. After baseball, he went on to a successful 23-year career as an executive with the Chrysler Corporation.

Born on November 9, 1925, in Panola, Alabama, William Haron Bruton grew up in a world of segregated baseball. As a youngster, he had access only to neighborhood sandlot baseball; his schools had no teams. However, he did have the opportunity to watch Birmingham Black Barons games, at which he saw many early black baseball stars including Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson.[4]

After high school Bruton went into the Army and spent six months in the Far East. Upon his return, he went to live with relatives in Wilmington, Delaware. There, he began playing softball on several community teams. He played catcher and batted from both sides of the plate. He found that when he batted right-handed he tended to hit pop flies. When he batted left-handed, he hit more line drives, so he chose to become a strictly left-handed hitter. He also caught the eye of the young daughter of Judy Johnson. With her encouragement, the elder Johnson went to watch Bruton play, and was impressed.

Bruton became equally taken with Johnson. Judy knew many former Negro Leaguers and they would congregate around his kitchen table and tell baseball stories for hours. Bruton took it all in. He loved talking baseball with Judy.

With Johnson’s help, Bruton got a tryout with the Philadelphia Stars, a Negro Leagues team. The Stars released Bruton at the end of spring training, and he began playing semipro baseball and barnstorming.

In 1950 Johnson again talked up Bruton to his friend Bill Yancey, who had played with Johnson in the Negro Leagues. Yancey in turn recommended Bruton to Boston Braves scout Jack Ogden. The Braves invited Bruton to their minor-league spring-training camp. He impressed the Braves enough to be offered a professional contract, and signed immediately.[5]

Bruton was 23 years old when he signed his contract. The veteran Yancey knew his age, but fearing that he might be viewed as too old by the Braves, reported it as 21. According to Yancey, the Braves later changed Bruton’s reported age to 19. His true age was not publicly disclosed until the day he retired from baseball.[6]

In 1950 the Boston Braves sent Bruton to Eau Claire in the Class C Northern League. Utilizing his tremendous speed, Bruton led the league in stolen bases (66), scored 126 runs, and hit .288. He was chosen the league’s Rookie of the Year. In 1951 Boston moved Bruton up to Denver in the Western League (Class B). This time he hit .303, scored 104 runs, and led the league with 27 triples. His performance caught the eye of Braves general manager John Quinn. On a Western trip, Quinn saw Bruton play and pronounced that he would someday be Boston’s center fielder.[7]

How quickly should Bruton, a player with obvious talent and enormous potential, move up toward the major leagues? Many in the Braves organization felt he could neither hit in the high minors nor use his speed effectively in the field. He remained vulnerable to pitcher pickoff moves and did not know how to effectively bunt.[8]

However, Charlie Grimm, manager of the Braves’ Triple-A team, the Milwaukee Brewers, saw a potential big leaguer. At the beginning of 1952, the Boston organization decided to let Bruton try to jump from Class B to Triple-A in one season. It would be a make-or-break situation for him.[9]

During 1952 spring training in Florida, The Sporting News reported an incident that showed the continued importance Bruton attached to his religion. Bruton and his teammates ate dinner together at their boarding house. Bruton requested that they say grace before each meal. Thereafter, pre-meal grace became an everyday practice.[10]

Grimm let Bruton start the season as the center fielder and leadoff hitter. Bruton quickly found that what he had done in Class B would not work in Triple-A. By midseason, it looked as if Grimm had made a big mistake. Nevertheless, Grimm continued to play Billy.

Bruton later acknowledged that Grimm’s patience was critical to his development. “I doubt if I’d even stayed up in Triple-A ball last year if someone besides Charlie was managing Milwaukee (Brewers). I was no help at all to the club. I didn’t hit at all, the first two and a half to three months. But Charlie kept me in the lineup. He stuck with me.”[11]

On May 31 the Braves fired manager Tommy Holmes and hired Grimm. He quickly made several roster moves, including optioning outfielder Jim “Buster” Clarkson to the Brewers. Bruton became friends with Clarkson, a veteran Braves minor-league player who had also played in the Negro Leagues. A college graduate in physical education, Clarkson began schooling Bruton on how to improve his game.

Bruton quickly turned his disastrous season around. He ended up playing in all 154 games and hit .325 for the season. His 211 hits led the American Association. In the last six weeks of the season, he stole 20 bases.

Bruton gave all the credit to Clarkson. “All I know about baseball, I owe to Bus Clarkson,” he said. “He taught me a lot.” After the season, Clarkson invited Bruton to play winter ball for a team he managed in the Puerto Rico League. Again, Clarkson provided Bruton with more baseball insight. This time they focused on his bunting.[12]

Based on his minor-league experience with Bruton and Billy’s good spring training in 1953, Grimm made him the Milwaukee Braves’ leadoff hitter and center fielder. The Braves, who had moved to Milwaukee in the offseason, started the 1953 season with one game in Cincinnati, played in front of an overflow crowd of 30,103. Bruton’s major-league debut was described as “sensational.” Three times he reached into the overflow crowd and caught certain extra-base hits. The Braves won, 2-0. Leading off, Bruton went 2-for-4 with a single and a double. He stole a base. After the game, winning Braves pitcher Max Surkont raved about Bruton, claiming he had been the primary difference between victory and defeat.[13]

The Braves’ next game, in Milwaukee against the Cardinals, marked the return of major-league baseball to Milwaukee after 51 years, and Bruton again provided key plays to help the Braves win. When the Cardinals threatened in the eighth inning, Bruton made a great catch of a Stan Musial blast for the third out. After the Cardinals tied the game in the ninth inning, Bruton hit a walk-off home run. He went 3-for-5. His home run was his only one in 1953.)[14]

Bruton continued to play a great center field. On May 16 the Chicago Cubs’ Hank Sauer, batting with a runner on second base, hit a short pop fly to center field. Bruton raced in and caught the ball at his shoe tops, then flipped it to second base to easily double up the runner. The sensational play prompted comparisons to the fielding of Tris Speaker, who also played a shallow center field.[15]

Described his fielding philosophy, Bruton said he played a shallow center field but had “no problems” going back to catch long flies. If somebody “hit a line drive to the center-field fence, he deserved a base hit,” Bruton said. If it wasn’t a line drive, “I knew I was going to catch it.”[16]

In 1953 Bruton played in 151 games and batted leadoff in all but three. He finished with a .250 batting average and stole a league-leading 26 bases. He had 14 triples. From center field he started five double plays, by catching the ball and picking off an advancing runner before he got back to his base. After the season the Milwaukee Chapter of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America named Bruton the Braves top rookie of 1953. Bruton was also chosen the year’s outstanding athlete from Delaware.[17]

In early 1954 Bruton suffered a string of minor injuries during spring training and in the first week of the season. A foot injury, an ankle injury, a pulled groin muscle, and a virus infection all happened between March 7 and April 18.[18] Still, Bruton starred in the Milwaukee home opener against the St. Louis Cardinals, scoring the winning run from first base on a single and an error. He continued displaying his spectacular, crowd-pleasing speed. In Pittsburgh Hank Aaron hit a fly to deep center field and Bruton scored from second base standing up. During the season, he had a 17-game hitting streak and a 26-game on-base streak.[19] He raised his batting average from .250 to .284. Bruton’s 34 stolen bases led the National League, but he was caught stealing a league-leading 13 times.

In his first two seasons, Bruton’s contribution to the potent Milwaukee offense was clear. The Braves stole 100 bases in 1953 and 1954. Bruton stole 60 of them, and in 1954 set a major-league record by getting 64.8 percent of his team’s stolen bases.[20]

During the offseason, Miller Brewing Company hired Bruton to make speaking appearances. During a trip to Wausau, Wisconsin, Bruton roomed with Bob Allen, the Braves’ media-relations director. At bedtime Billy began praying. When Allen asked him why, Bruton told him that as a kid he dreamed of playing in the major leagues but “knew” it could never happen. Now he was paid to play with Hank Aaron and Warren Spahn. So he thanked God every day for watching over him and his family.[21]

Bruton began 1955 focused on lowering his strikeouts and increasing his walks. He had fanned 178 times and walked 84 times in 1953 and 1954. Bruton slightly widened his batting stance and crouched at the plate to get a better view of the pitch and create a smaller strike zone.[22] He still struck out 72 times and got only 43 walks that season.

The Braves started their 1955 season at home against the Cincinnati Reds. With the game tied at 2-2, Bruton singled and scored the winning run on a triple by Hank Aaron. It was the third year in a row that he had scored the winning run in the Braves’ home opener.[23] For the season he hit .275, led the league with 636 at-bats and scored 106 runs. He recorded personal bests in home runs (9), doubles (30), and RBIs (47). Bruton continued to try to use his speed to disrupt opposing teams, leading the National League for the third consecutive year with 25 stolen bases. He set a Braves record by hitting into only two double plays during the season.

Bruton started the 1956 season slowly. The Braves dropped him to seventh in the batting order, and he hit .459 in his first 11 games of the season.[24]

On June 16 manager Charlie Grimm resigned and was replaced by Coach Fred Haney. The change directly affected Bruton. As a player Haney was also a good base stealer. However, he strongly believed things had changed from when he played. With bigger rosters and more power hitters, he believed, base stealing should be more selective.[25] He decreed that no player could try to steal without his approval. Bruton had only eight stolen bases for the season. Meanwhile Haney highly valued the sacrifice bunt, and Bruton ended with a career-high 18 sacrifices. He finished the season with a .272 batting average for the season. His 15 triples led the NL. On September 23 he hit the first grand slam of his career. On July 11, 1957, Bruton, going for a Texas leaguer in left-center field, collided with Braves shortstop Felix Mantilla and tore a ligament in his right knee.[26] Bruton knew knee surgery would put him out for the year. Many thought he would never play again. He elected to wait and see if rest and other treatment would help.[27] Upset about his future, the intensely religious Bruton began serving as a radio disc jockey for a Sunday-morning hour program of religious music.[28] The Braves won the pennant. As they played the first game of the World Series against the New York Yankees, Dr. Don H. O’Donoghue was operating on Bruton’s knee in Oklahoma City. After the surgery, O’Donoghue predicted that Bruton would be ready for 1958 spring training. Billy was ecstatic.[29] In late January O’Donoghue and the Braves’ team doctor agreed that Bruton’s knee was healing as expected and he was cleared to report to spring training.[30] But Bruton didn’t get into a game until May 25 in Milwaukee. As he approached the plate for the first time, he received a thunderous ovation from the 40,963 in attendance, and then hit the first pitch into right field for a single. Bruton later made a circus catch in center field.[31] For the season he played in 100 games and hit.280.

The Braves again won the pennant, giving Bruton the opportunity to play in his first World Series. In the first game, in Milwaukee, he hit a two-out single in the tenth inning to drive in the winning run against the Yankees. In Game Two Bruton hit a home run to lead off the game in another Braves victory. The Braves lost the Series in seven games, but Bruton hit .412. He later characterized playing in the 1958 World Series as the biggest thrill of his career.[32]

In 1959 Bruton appeared in 133 games primarily as the leadoff hitter (83 games) and hit a career-high .289. On August 2 he became the fourth major leaguer to hit two bases-loaded triples in a game. His hits came against Cardinals left-handers Vinegar Bend Mizell and Dean Stone.[33] Tied during the regular season, the Los Angeles Dodgers and the Braves had a best-of-three playoff for the pennant. The Dodgers swept, and limited Bruton to one hit in ten at-bats.

In November the Braves fired Haney and hired Chuck Dressen as the manager for 1960. The 34-year-old Bruton remained the leadoff man and center fielder, and had one of his best seasons. He hit .280 and led the National League in runs scored (112) and triples (13). He hit a career high 12 home run, had a 27-game on-base streak and a 15-game hitting streak.

Despite Bruton’s 1960 heroics, the Braves dealt him to the Detroit Tigers in a five-player trade. Bruton had spent eight years in Milwaukee and batted.276. For three consecutive seasons (1953-1955), he led the NL in stolen bases. He led the league in triples twice.

Bruton played four years with Detroit before retiring, as a regular the first three years and as a reserve in his final year. He hit .257 in 1961 with a career-high 17 home runs. In 1962 he hit .278 with 16 home runs and a career-high 74 RBIs. He also hit his second grand slam. He posted a .256 average in 1962 and finished with a .277 mark in 1964. In 12 years as a major leaguer Bruton finished with a .273 batting average.

Bruton’s retirement came about after the Chrysler Corporation offered him a job paying $15,000 a year. Although he was making $28,000 as a player, Bruton knew he was close to the end of his playing career. He announced his retirement on September 27 before the final home game of the season. In making the move, he said his priority was his wife and four children. “A chance like this doesn’t come too often,” he said.[34] In his final game in Detroit, before a small crowd, Bruton blasted a home run into the upper deck in right field at Tiger Stadium. Later Bruton’s wife confessed, “That had me scared. … I was afraid that Billy might change his mind.”[35]

On November 21, at a reception in his honor, Chrysler formally announced his hiring for the automaker’s merchandising staff. Tigers vice president Rick Ferrell said, “Bruton is the best player I’ve ever seen retire. Usually, you have to cut the uniform off a guy to make him quit. Billy can still run and throw and hit the ball.”[36]

Bruton spent the next 23 years as an executive with Chrysler, working primarily in the company’s Detroit headquarters. He worked in sales, customer service, promotion, and financing. He later owned a Chrysler dealership. He finished his career as a special assistant to Chrysler president Lee Iacocca. He retired in 1988.

In 1989 Billy returned to Delaware with his wife to live in his father-in-law Judy Johnson’s old residence in Marshalltown. He continued his work with several churches and charitable organizations, particularly the Big Brothers-Big Sisters of Delaware.

With a history of heart problems, Bruton died of an apparent heart attack on December 5, 1995, while driving near his home. He was 70 years old. The State Police said they found him slumped over the wheel of his car, which had hit a pole. He was buried with an American flag draped over his coffin as an acknowledgement of his military service.[37]

This biography is included in the book “Thar’s Joy in Braveland! The 1957 Milwaukee Braves” (SABR, 2014), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. To download the free e-book or purchase the paperback edition, click here.

Notes

[1] Bill James, The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2001), 768.

[2] Tom Tomashek, “Bruton Lauded as quiet force,” The News Journal, Wilmington, Delaware, December 9,1998, A16; Jeff Williams, “Judy Johnson home named historic site,” The News Journal, November 5,1995.

[3] Paula Parrish, “Ballplayer Bill Bruton Dead at 69,” The News Journal, Wilmington, Delaware, December 6, 1995, A-4

[4] Rich Westcott, Splendor on the Diamond (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2000), 257.

[5] Sam Levy, “Bruton’s a Big Man in Milwaukee,” Baseball Digest, July 1953, 60

[6] Watson Spoelstra, “Luncheon Gives Bruton a Fast Sendoff on Career at Chrysler,” The Sporting News, November 21,1964, 9

[7] HOF Bill Bruton Player Clippings File as of September 14, 2012, unidentified author, “Bruton’s Triples in ’51 Sold Quinn,” The Sporting News, December 30,1953, 3.

[8] Sam Levy, “Bruton Helps to Banish Cholly’s Outfield Worries on the Braves,” The Sporting News, April 15, 1953, 17

[9] Roger Birtwell, “Braves Bill Bruton for Picket Post,” The Sporting News, December 24, 1952

[10] Oscar Ruhl, “Ruhl Book,” The Sporting News, April 2, 1952, 14.

[11] Sam Levy, “Bruton’s Big Man in Milwaukee, Baseball Digest, July 1953, 13, 14.

[12] Ibid, 59

[13] Ibid, 60

[14] Sam Levy, “Milwaukeeans Lift Merry Mugs to Braves,” The Sporting News, April 22, 1953, 13.

[15] Ed Prell, “Milwaukee Backing Its Battling Braves in Big League Style,” The Sporting News, May 20, 1953, 6.

[16] Norman Macht, “Billy Bruton Recalls How the Game Was Played in the 1950s,” Baseball Digest, August 1990, 44-48.

[17] “Milwaukee Writers Name Mathews Braves’ Top Star,” The Sporting News, December 9, 1953, 24.

[18] “Injury List Already Higher Than in Entire ’53 Season,” The Sporting News, February 28, 1954, 15.

[19] “Bruton Still a Card Jinx”, The Sporting News, April 28, 1954, 21, Red Thisted, “Banjo Cholly Can’t Keep His Hurlers and Hitters in Harmony,” The Sporting News, June 30,1954, 9 Baseball-Reference.com: Bill Bruton 1954 Gamelogs, Longest Hitting Streak, Longest On Base Streak; Bill Bruton Statistics and History, 1954

[20] “Bruton, Champ Base Thief, Bags His First Steal of Year,” The Sporting News, May 11, 1955, 19.

[21] Tom Tomashek, “Bruton lauded as quiet force,” The News Journal, Wilmington Delaware, December 9,1998, A16

[22] “Bruton Credits Speedy Start to Wider Stance and Crouch,” The Sporting News, May 4, 1955.

[23] “Bruton ‘Mr. Win’ of Braves,” The Sporting News, April 20, 1955, 24.

[24] “Bruton Likes Seventh Spot; Hits .459 in First 11 Games,” The Sporting News, May 16, 1956, 10.

[25] Bob Wolf, “Base Stealing a ‘Lost Art,’ Moans Ex-Speedster Haney,” The Sporting News, March 28, 1956, 23.

[26] Bob Wolf, “Braves Beaming Despite Rash of Aches’ n’ Breaks,” The Sporting News, July 31, 1957, 11. \

[27] Bob Wolf, “Bruton’s Return to Duty Ties Up Hazel Tepee Tale,” The Sporting News, June 4, 1958, 9.

[28] “Tuning In,” The Sporting News, August 21, 1957, 30.

[29] Curt Mosher, “Bruton Undergoes Surgery on Knee, Expected to Be Ready Next Spring,” The Sporting News, October 23, 1957, 14.

[30] “Bruton to Report on Time: Knee Healing Satisfactorily,” The Sporting News, January 29, 1958, 13.

[31] Bob Wolf, “Bruton’s Return to Duty Ties Up Hazle Tepee Tale,” The Sporting News, June 4, 1958,9

[32] Westcott, Splendor on the Diamond, 262.

[33] “Bruton 4th Major Leaguer to Rap 2 Three-Run Triples,” The Sporting News, August 12, 1959, 23.

[34] Watson Spoelstra, “Bruton Waves Bye: Bengals Eye Farms For Flyhawk Talent,” The Sporting News, October 10, 1964.

[35] Watson Spoelstra, “Luncheon Gives Bruton a Fast Sendoff on Career at Chrysler,” The Sporting News, November 21, 1964, 9.

[36] Ibid

[37] Ibid

Full Name

William Haron Bruton

Born

November 9, 1925 at Panola, AL (USA)

Died

December 5, 1995 at Marshallton, DE (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.