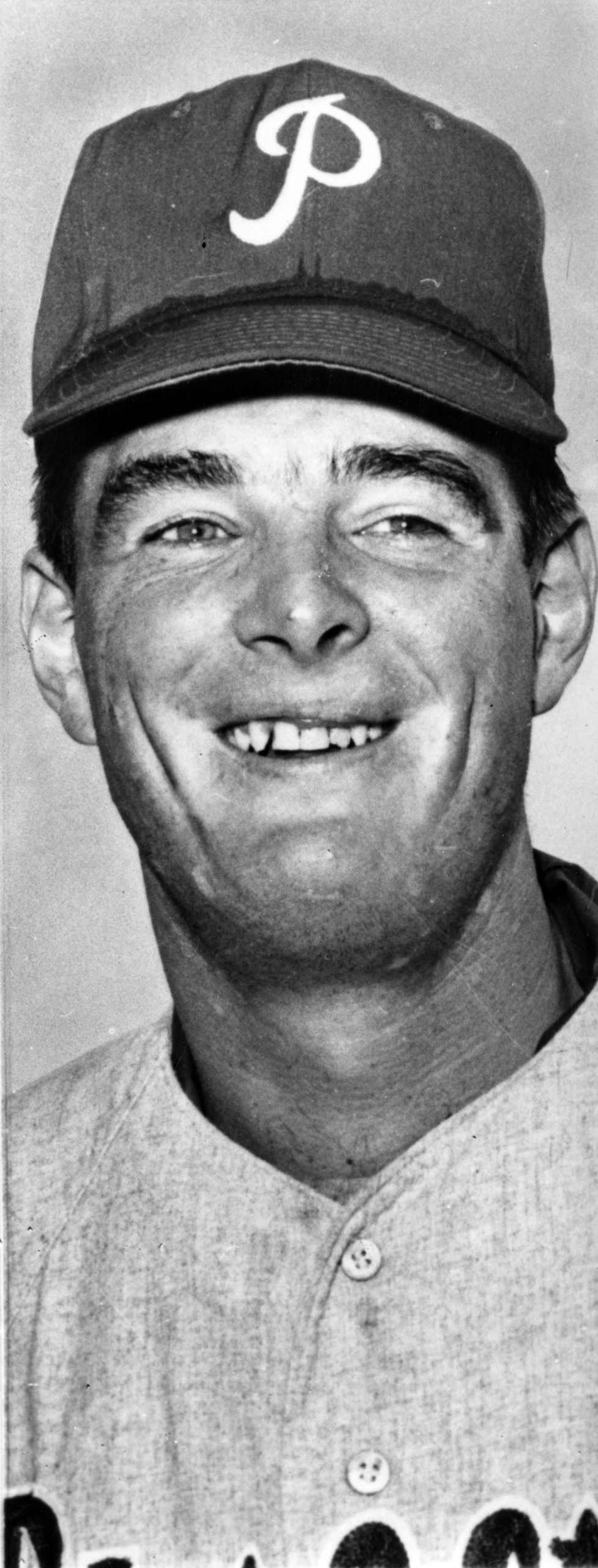

Dennis Bennett

Dennis Bennett, a member of the Phillies’ pitching rotation in 1964 and a fun-loving character on baseball’s stage for much of the 1960s, was blessed with a great left arm and a thirst for the good life. He also overcame several reckless brushes with danger, including a tragic accident, to forge a seven-year big-league career, though not reaching the heights he likely could have.

Dennis Bennett, a member of the Phillies’ pitching rotation in 1964 and a fun-loving character on baseball’s stage for much of the 1960s, was blessed with a great left arm and a thirst for the good life. He also overcame several reckless brushes with danger, including a tragic accident, to forge a seven-year big-league career, though not reaching the heights he likely could have.

Dennis John Bennett was born in Oakland, California, on October 5, 1939, to parents George and Ruth, of German-Dutch descent. There were ultimately five boys and a girl in the Bennett family. The family moved to Yreka, a heavily wooded town in Northern California’s Siskiyou County, when Dennis was 10 years old. (His father liked to hunt and fish, and when a job with the phone company opened up nearer his beloved streams and forests, he took it.) The elder Bennett started the boys’ baseball program in Yreka, and Dennis soon became a star first baseman and hitter. He played Little League and Babe Ruth League baseball before entering high school.

At Yreka Union High School, Dennis lettered in baseball, basketball, track, and football. In his senior year, he won 15 of 16 decisions on the mound and hit .458, playing first base when not pitching. He was, however, not fond of rules. “I can’t remember a single season where I wasn’t suspended for at least one game,” he later recalled.1

Dennis’s off-the-field activities in his youth were atypical. Firefighting was a vital and lucrative occupation in his region, so he often skipped school to go off and join a fire crew (lying about his age). If that wasn’t dangerous enough, he and some friends made extra money in the summers traveling around Northern California to various rodeos, riding saddleback and bareback bronco events. He later recalled, “Sometimes I was hit over the head with bottles or cut up in a fight at a dance, but I was lucky. All those rodeos, I never got banged up.”2

Bennett did not throw particularly hard as a teenager, and few scouts showed any interest in watching the hurler. He garnered a partial scholarship to pitch for Mount Shasta Junior College, pitching a single season for its baseball team. At that point, Bennett was offered a contract by Eddie Taylor, a scout for the Philadelphia Phillies. He was no bonus baby– he would get $500 if he stayed in the organization for 90 days, and $250 a month.

Bennett’s professional career began in Johnson City, Tennessee, in the Appalachian League, where the 6-foot 3-inch, 192-pound left-hander finished 7-3 and led the league with three shutouts and a 1.52 earned-run average and struck out 92 in just 77 innings. The next year he finished 13-13 for Bakersfield in the California League, before spending the 1960 campaign with Asheville, North Carolina (South Atlantic League), where he finished 8-7.

He spent the start of 1961 in Chattanooga (4-2, 4.37) before tearing up his knee. The circumstances surrounding the injury typify the personality of Bennett, always a free spirit. “There was a big hill in right field in Nashville. A bunch of us were standing around, and I challenged John Boozer to a somersault race downhill. It was for $10 and a steak dinner.”3 He lost the bet and jammed the cartilage in his knee. An operation ended his season. He told his manager he got hurt jogging in the outfield.

The next spring Bennett was invited to major-league camp, likely because the Phillies wanted to see how his knee was. Not only was his knee fine, the rest had added several miles per hour to his fastball. He was sent to Triple-A Buffalo (International League), and started 3-1, 2.00 before his recall to Philadelphia in May.

Bennett’s first major-league appearance took place at Chicago’s Wrigley Field on May 12, 1962. The Phillies were leading 8-5 when he took the mound to start the bottom of the fourth inning. He walked his first batter, Lou Brock, before inducing a double-play groundball. After three scoreless innings, Bennett could not escape the seventh, allowing three hits and a walk before being relieved. (Bennett was charged with three earned runs. He was credited with a hold in the 9-8 loss. The pitcher who followed Bennett, Chris Short, was given a blown save.)

After three mediocre starts, Bennett’s first major-league victory was a four-hit shutout that snapped the Los Angeles Dodgers’ 13-game winning streak on June 2. He finished the season 9-9, leading the team with a 3.81 ERA and two shutouts. From August 12 to the end of the season, his ERA was 1.66, highlighted by three consecutive five-hit complete games. Bennett later recalled, “I figured I had a great career ahead of me. I knew I could throw. I wasn’t a complete pitcher or the smartest guy out there, but at that time if you threw hard enough you learned as you went. I was real happy the way everything was going at that point.”4

The Phillies sent Bennett to Arecibo, Puerto Rico, that winter to get ready for a big season. On January 7, 1963, returning to Arecibo from a team picnic, he was involved in a car accident that killed the driver. Bennett was thrown through the windshield, breaking his left ankle, pelvis, and left shoulder blade, and leaving severe lacerations all over his face. He had been sitting with his back against the door and leg up on the seat, talking to the people in the rear seat. According to Bennett, this was his fifth serious car accident and the third time he had been thrown through the windshield. This was the first time he was seriously hurt.

The Phillies were most concerned with Bennett’s ankle, but it was the shoulder injury that would linger, and cause problems throughout the remainder of his career. The doctor in Puerto Rico suggested he would never pitch again, and might not walk. After months in the hospital, Bennett was working out by the end of May and, miraculously, joined the Phillies in late June. By July he was in the rotation, and he pitched very well the rest of the season, finishing 9-5, with a 2.64 ERA. For his efforts he won a local award as the most courageous athlete on the team. The shoulder seemed fine—for now.

Bennett was cocky when assessing his chances for 1964: “There’s no way they can stop me from winning 20. I have always done real well early in the year, but my first two years in the big leagues I haven’t been out there.”5 He elaborated in a July profile Stan Hochman wrote for Sport: “You can’t go out there wondering whether you are going to win or lose. You can’t look at the hitter and say, ‘Geez, that’s Henry Aaron … or geez, that’s Willie Mays.’ Now, I don’t care who’s up there.”6

Bennett’s manager, Gene Mauch, was also unconcerned: “He’s got a big-league fastball and two breaking balls that are better than the average major leaguer. And he believes in himself about 130 percent.”7 Bennett later named Mauch as his favorite manager, a brilliant man that people loved playing for.

Dennis was beginning to acquire a reputation as a free spirit, who enjoyed the nightlife. He was single and spent his evenings doing what single men are wont to do. “You’ll never catch me out the night before I pitch. But I figure a pitcher has two nights to fool around.”8

Bennett started strong in 1964, winning eight of his first 12 decisions through June. His personal highlight took place on June 12 in a game in which he was knocked out of the box by the New York Mets in the third inning. Later in the game, his brother Dave Bennett made his major-league debut, pitching the ninth inning for the Phillies in what turned out to be an 11-3 loss. Dave was just 18 years old, a 6-foot-5 right-hander who possessed none of his older brother’s swagger or brashness. Alas, this was to be Dave’s only major-league appearance.

In the second half of the 1964 season, Dennis’s shoulder, and its still undiagnosed injury, started to bother him and the pain never really went away again. He managed just a 1-7 record in July and August, ironically as his team started pulling away in the pennant race. On September 7 he beat the Los Angeles Dodgers 5-1, and followed with a 1-0 victory over Juan Marichal and the San Francisco Giants. After he followed with a 1-0 victory over the Houston Astros on the 15th, the Phillies had a six-game lead over the St. Louis Cardinals with 17 games to go. Bennett started three more times, losing two, and the Phillies lost a heartbreaking pennant race. By season’s end the pain in his shoulder was constant and tremendous. Bennett finished 12-14, with a 3.68 ERA.

The 1964 Phillies are one of the more famous teams in Philadelphia history, and Bennett’s injury was likely the biggest cause of their collapse. He was the club’s Opening Day starter, and an ace hurler for the first half of the season before the sore shoulder took over. Bennett said he believed the team would have won the pennant “hands down” had his arm stayed healthy, and listed it among his biggest disappointments. He later recalled his shutout of the Giants in September as the best of his career, a game notable for his three strikeouts of Willie Mays. Mays hit just .111 (3-for-27) off Bennett in his career, and Willie McCovey was 0-for-8 with five strikeouts, while their teammate Jim Ray Hart, whom Bennett recalled decades later as a nemesis, managed a more robust .533 with three home runs.

On November 29, 1964, the Phillies dealt Bennett to the Boston Red Sox for slugger Dick Stuart. Bennett was angered by the deal because he felt the team had promised him he would be back with the club. More than that, he knew he was hurt and felt the Phillies knew it. Bennett was speaking at a banquet in Boston that winter and surprised the assembled media and team personnel when he casually mentioned that his sore arm might not be ready for the opening of the season. The Phillies offered to nullify the deal, but the Red Sox were happy to be rid of the enigmatic and controversial Stuart and left it alone.

As a left-hander moving to Fenway Park, Bennett acknowledged, the wall in left field “messed with my mind a little.”9 Balancing that, he believed there were far fewer tough outs in an American League lineup compared with his National League opponents. Bennett pitched adequately for the 1965 Red Sox, starting 18 games and relieving in 16 others, finishing 5-7 for a team that lost 100 games. He started the season on the disabled list, joining the club in early May. During his recuperation, he vowed to host a champagne party for the writers after his first victory, a promise he kept after topping the Kansas City Athletics at Fenway Park on May 31. The thankful writers allowed that they would return the favor after his first shutout.

Bennett’s reputation for zaniness grew. For one thing, he carried several guns with him on the road, and often on his person. He told the story of shooting off several rounds with a gun one quiet spring just over the head of Boston Globe writer Will McDonough, who had written a story Bennett did not like. “So me and Will didn’t see eye to eye for the rest of my time there,” he recalled.10 Then there was the time Bennett shot out the lights in his hotel room, to save getting up and turning the switch.

After the 1965 season Bennett finally underwent shoulder surgery, which kept him on the disabled list until mid-July. A doctor finally isolated the problem— calcium had built up in a crack in the shoulder blade caused by his 1963 accident. Bennett recalled that pitchers tended to throw through such problems back then, but the Red Sox supported his decision to have surgery. Upon his return, he was actually one of the more steady members of the rotation, finishing 3-3 with a 3.24 ERA in 13 starts for an improving club that played .500 ball in the second half.

The next spring Bennett was involved in an incident in Florida that was part of a sad lineage of race relations with the Red Sox. He entered a club in Lakeland with pitchers Dave Morehead and Earl Wilson. While Bennett and Morehead were asked for their drink orders, the bartender turned to Wilson, an African-American, and said, “We ain’t serving you. We don’t serve niggers here.”11 The players left, but word of the incident soon leaked out. The club did not strongly back Wilson, who was traded in June. He won 13 games in the latter half of the season for the Tigers, and 22 the next year.

Bennett later related to Peter Golenbock what these Red Sox teams were like: “You’d have four or five players and some girls, and you’d have a party. And it might go until six, seven in the morning, and maybe you had a day game that day. And the thing was, you’d get on the bus, and [manager] Billy Herman would be sitting in the front seat, and everybody would talk about the party the night before, and Billy would sit there hearing it all, but there wasn’t too much he could do about it because some of your stars were the ones doing the talking, and he didn’t have any control over the ballclub whatsoever.”12

The new manager for 1967, Dick Williams, was different. When Bennett and another pitcher showed up late one day in the spring, Williams publicly called them out and fined them. When Bennett blamed the hotel for failing to give him his wakeup call, Williams ridiculed the players, and Bennett never got out of the new skipper’s doghouse.

Dennis continued to pitch well early in the 1967 season. He started the fourth game of the season, following Billy Rohr’s one-hitter in Yankee Stadium with a five-hit, 1-0 loss to the same Yankees on April 15. On May 1 in Anaheim, he shut out the Angels with a six-hitter, and also hit a three-run home run off Angels starter Jorge Rubio. After surrendering the round-tripper, Rubio hit Reggie Smith with a pitch, then was removed from the game. This was his 10th major-league game, and his last. Bennett was doubly happy about the shutout, as the local writers had promised him a champagne party two years ago with his first such gem. They came through, holding it at the Playboy Club in Boston.

When Bennett beat the Indians’ Gary Bell on June 3, he brought his record to 4-1, with a 2.97 ERA. After a couple of rough starts, he fell to 4-3, and his relationship with Williams deteriorated further. On June 24 the Red Sox traded Bennett to the Mets for minor leaguer Al Yates, who would never pitch for the Red Sox. According to Bennett, Williams had not spoken to him in a few weeks prior to telling him he had been dealt. The pitcher expressed disappointment at the trade, telling the New York writers that he thought a good team was coming together in Boston.

Bennett split two decisions with the Mets, also spending time with their Jacksonville affiliate in the International League. After two appearances for Jacksonville in April 1968, he was sold to the Chicago Cubs organization, which placed him with Tacoma in the Pacific Coast League. He was 9-8 in 19 starts out west, and at the end of July was sold to the California Angels. He finished the season, and his big league career, by dropping all five of his decisions for the Angels.

But Bennett wasn’t through pitching just yet. He spent the next five years in the Pacific Coast League, much of it far removed from the continental United States. He played for Hawaii in 1969 and 1970, tying for the league lead each year in victories (13 and 18) and making two All-Star teams. These Hawaii clubs were great teams, filled with ex-major leaguers. The 1970 team finished 98-48, and was led by Bennett, Gary Bell, Juan Pizarro, and several other former big leaguers.

Bennett spent a year and a half with Salt Lake City before returning to Hawaii for parts of the 1972, and 1973 seasons. At the conclusion of the latter campaign, he finally walked away from the game.

Bennett married Terry, whom he had met in Boston, on January 3, 1970, and the two raised nine children. Having settled in Klamath Falls, Oregon, Bennett operated a restaurant and bar for a few years, worked for several years in a mill, operated another bar, and finally opened a more elaborate club with banquet rooms in 1998. In 2010 he and his wife owned a four-story commercial building in town that housed a boutique, an interior decorator shop, and a hall for banquets and parties.

In the 1990s Bennett was the victim of identity theft – a man in Texas successfully passed himself off as the former major-league pitcher, sticking the real Bennett with tens of thousands of dollars in bills, including $77,000 for open-heart surgery. As he later told researcher Todd Newville, “It caused me a lot of misery for several years. It’s all water under the bridge now, but for about five years, I couldn’t even buy a pack of gum on credit. That’s how bad that guy ruined it.”13

Klamath Falls is a small community when compared with the big metropolises in which Bennett spent his pitching career. His businesses and big family kept him at home most of the time, but he attended many reunions and fantasy camps over the years. He kept many dear friends from his playing days, including Gary Bell, Dave Morehead, Jim Lonborg (his roommate with the Red Sox), and Chris Short, his best friend on the Phillies, who died too young in 1991. He valued all his old baseball memories, and loved getting together with his old teammates and opponents. He returned to Fenway Park in 2007 for several events honoring the 1967 team.

“Baseball was the best time of my life,” Bennett later recalled. “I couldn’t throw without pain for most of the time after the wreck. If I hadn’t cracked my shoulder blade in the accident, I think I would have had one hell of a career.”14 Asked many years later to recount the highlight of his big-league career, he said simply, “Just being there was the highlight. Playing against all those great players.”15

Dennis Bennett passed away on March 24, 2012, at home in Klamath Falls, surrounded by friends and family.

A version of this biography originally appeared in “The 1967 Impossible Dream Red Sox: Pandemonium on the Field” (Rounder Books, 2007), edited by Bill Nowlin and Dan Desrochers. It was updated and included in “The Year of the Blue Snow: The 1964 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2013), edited by Mel Marmer and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Stan Hochman, “He Walks and Talks With a Swagger,” Sport, July 1964.

2 Dennis Bennett, interview with author, May 26, 2006.

3 Hochman, “He Walks and Talks.”

4 Bill Ballew, “Dennis Bennett operates real-life ‘Cheers’,” Sports Collectors Digest, June 16, 1995: 146.

5 Allen Lewis, “Breezy Bennett to Stir 20-Win Whirlwind for Phils, He Says,” unidentified clipping Bennett’s Hall of Fame file, February 1, 1964.

6 Hochman, “He Walks and Talks.”

7 Hochman, “He Walks and Talks.”

8 Hochman, “He Walks and Talks.”

9 Ballew, “Dennis Bennett,” 146.

10 Peter Golenbock, Fenway: An Unexpurgated History of the Boston Red Sox (New York: Putnam, 1992), 288.

11 Golenbock, Fenway, 229.

12 Golenbock, Fenway, 288-289.

13 Todd Newville, “Against The Odds!” Todd’s Baseball Dugout web site (disbanded), retrieved May 2006.

14 Ballew, “Dennis Bennett,” 146.

15 Dennis Bennett, interview with author, February 25, 2010.

Full Name

Dennis John Bennett

Born

October 5, 1939 at Oakland, CA (USA)

Died

March 24, 2012 at Klamath Falls, OR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.