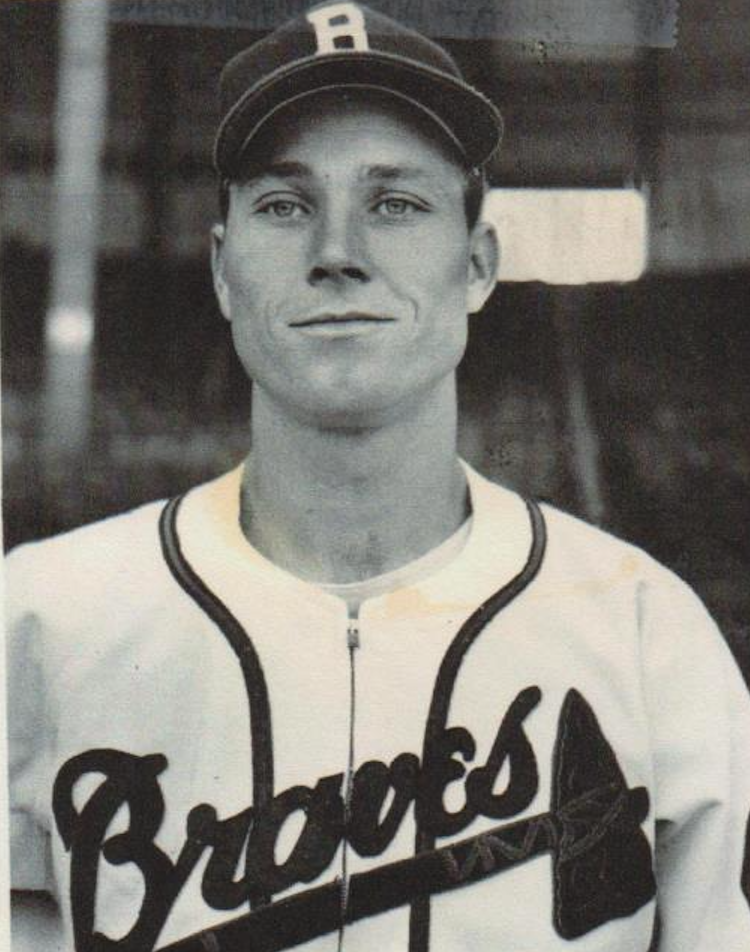

Carden Gillenwater

Had World War II continued indefinitely, Carden Gillenwater might have fashioned a noteworthy major-league career. As a member of the 1945 Boston Braves, he posted solid offensive numbers and led National League center fielders in several fielding categories. But the return of baseball’s elite for the 1946 season soon relegated placeholders like Gillenwater back to the bushes. Apart from a stint as a part-timer for the Washington Senators in 1948, Gilly was remanded to high-tier minor leagues until he hung up his spikes at the end of the 1954 season. Thereafter, he and his wife relocated to Clearwater, Florida, where they operated a chain of retail fabric stores for 25 years. After an active, travel-and-golf-filled retirement, Gillenwater was stricken with ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease) and died in a Florida nursing home in May 2000, just days short of his 83rd birthday.

Had World War II continued indefinitely, Carden Gillenwater might have fashioned a noteworthy major-league career. As a member of the 1945 Boston Braves, he posted solid offensive numbers and led National League center fielders in several fielding categories. But the return of baseball’s elite for the 1946 season soon relegated placeholders like Gillenwater back to the bushes. Apart from a stint as a part-timer for the Washington Senators in 1948, Gilly was remanded to high-tier minor leagues until he hung up his spikes at the end of the 1954 season. Thereafter, he and his wife relocated to Clearwater, Florida, where they operated a chain of retail fabric stores for 25 years. After an active, travel-and-golf-filled retirement, Gillenwater was stricken with ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease) and died in a Florida nursing home in May 2000, just days short of his 83rd birthday.

The memorably-named Carden Edison Gillenwater1 was born on May 13, 1917, in Riceville, Tennessee, a farming hamlet about 60 miles southwest of Knoxville. He was the youngest of the 10 children born to produce merchant William M. Gillenwater (1873-1949), and his wife, the former Florence Carden (1874-1956).2 The 1920 US Census places the Gillenwaters in Jacksonville, Florida, but by the time that their youngest child entered school, the family had permanently settled in Knoxville. A natural athlete, Carden developed into a two-sport (football and baseball) star at Knoxville High School.3

According to an anecdote recorded in Gillenwater’s personal journal, he first met baseball executives as a 15-year-old. Perched in a tree outside a Knoxville ballpark, he caught a Babe Ruth exhibition-game homer barehanded and thereafter surrendered the ball to a Yankees official and the president of the Southern League, mistaking them for plainclothes detectives sent to retrieve it.4 In August 1936 Carden was spotted playing summer baseball by Branch Rickey Jr., son of the visionary St. Louis Cardinals general manager, and invited to attend a local Cards tryout camp. Gillenwater was one of only two prospects (out of a reported 1,500) signed to a pro contract after the tryouts.5

Two months after his belated graduation from Knoxville High in January 1937, the soon-to-be 20-year-old Gillenwater reported to the Cardinals’ spring camp and attracted almost immediate notice. Although young and raw, Carden Gillenwater just looked like a ballplayer. Good-sized (6-feet-1,6 175 pounds) and athletic, the right-handed youngster was blessed with the foot speed and strong throwing arm of a top-notch outfielder and quickly impressed with his defensive skills. But his hitting, particularly a lack of extra-base power, made Gillenwater something of a project. Assigned to the Kinston (North Carolina) Eagles, a Class D affiliate of the St. Louis club, he got off to a good start, batting .301 with a surprising 14 homers (a figure that he would not reach again until the 1944 season).

Jumped all the way to the Cardinals’ Double-A International League farm club in Rochester, Gillenwater continued to progress in 1938. But he showed little power at the plate (only one home run), and was plagued by the minor injuries that would dog his entire career. Two injury-related stints on the Red Wings’ bench were topped off by a midgame trip to a Jersey City hospital in early September for an emergency appendectomy.7 In spite of it all, Gillenwater managed a .278 batting average in 111 games against top-flight minor-league pitching, and St. Louis GM Rickey reportedly saw a “bright future” ahead of his young farmhand.8

Gilly returned to Rochester for the 1939 campaign but seemed to take a step backward. A midseason sinus condition limited him to 99 games, and he hit only .252 with little power (only 17 extra-base hits in 314 at-bats). Dropped down to the New Orleans Pelicans of the Class A1 Southern Association, he rebounded in 1940. He hit .305, with 51 extra-base hits (but only four homers), and played a standout defensive center field. New Orleans sportswriter Val Flanagan wrote that Gillenwater “covers centerfield like a circus tent. He’s as fast as an antelope and can go far back to snag long flies, as many rival batters can testify.”9 Such play earned him a late-1940 season call-up to the Cardinals.10

Carden Gillenwater made his major-league debut in the first game of a September 22 doubleheader against the Chicago Cubs. With the Cardinals cruising to an 8-1 win, manager Billy Southworth sent Gillenwater out to relieve center fielder Terry Moore during the late innings. He then made his debut a complete success by singling off reliever Clay Bryant in his first major-league at-bat. Before the St. Louis season was over, Gilly made six more game appearances, finishing with an underwhelming .160 (4-for-25) batting average and five RBIs. His play in the outfield, however, was flawless, with 12 chances accepted without a misplay.

Gillenwater attended the Cardinals’ 1941 spring camp, but was optioned to Columbus (Ohio) of the Double-A American Association in early April. Days before the season began, Gilly formed an association of a different order: He married 22-year-old Marian King of Knoxville. Their union would be a long (59 years) and happy one, but produced no children.

Gillenwater was so-so in Columbus, batting .265 in 66 games. In mid-July, a four-player swap of Cardinals farmhands brought him back to Rochester,11 where his bating improved marginally (.283 in 42 games). Gillenwater played excellent defense in both venues, but his lack of power (only one home run in 335 at-bats, combined) was becoming a cause for alarm. In the offseason, he was demoted again, sold outright to New Orleans.12

Once the country entered World War II in December 1941, the military draft status of professional ballplayers became a front-office concern. But for the time being, married men like Gillenwater were not immediate conscription targets. He reported to New Orleans for spring training but got off slowly in 1942, set back by surgery in March to remove three bone chips in his throwing elbow.13 He returned to the lineup early in the regular season, but his final stats, a .273 batting average with four homers in 499 at-bats, again failed to impress.

With his career seemingly headed in the wrong direction, Gillenwater revived his prospects with a sterling 1943 campaign. Not only did he remain “one of the finest fielding outfielders in baseball,”14 Gilly began hitting. Despite being sidelined for weeks with a broken hand, he posted a .333 batting average with 30 extra-base hits in 109 games for New Orleans. That September the manpower-strapped Brooklyn Dodgers purchased his contract.15 With the Dodgers well out of pennant contention, Gillenwater was among the club newcomers thrown into action by manager Leo Durocher. In eight games, Gilly batted a meager .176 (3-for-17), but handled himself capably in the outfield. Given wartime conditions, it was enough for Brooklyn to reserve him for the 1944 season.

When the Dodgers reassembled for spring camp, Carden Gillenwater was among a host of roster members classified as 4-F, registrant not qualified for military service.16 The basis for this classification is uncertain. According to New York Times sportswriter Roscoe McGowen, the disqualification was “probably a result of a severe head injury [Gillenwater] suffered while playing centerfield for Rochester in an exhibition game several years ago.”17 A more likely basis for the 4-F classification was the significant hearing loss that Gillenwater suffered after a minor-league beaning by Hod Lisenbee.18 Whatever the basis, Gilly’s exemption from military duty greatly enhanced his chances of sticking with Brooklyn. But with a surplus of outfield candidates in camp, Gillenwater was deemed expendable and was optioned to the St. Paul Saints, the Dodgers’ affiliate in the American Association.

With St. Paul, the now-27-year-old Gillenwater began to flash bat power not previously seen in his seven-year pro career. His 53 extra-base hits included 19 home runs, a new career best, as were his 111 runs scored and 70 RBIs. A .296/.393/.478 slash line also reflected a surge in his offensive production. By late August, Gillenwater was reportedly among the Dodgers’ September call-ups.19 But he saw no 1944 game action for Brooklyn, and in the ensuing offseason Gillenwater was sold to the Boston Braves.20

To prepare for perhaps his last major-league chance, Gillenwater spent the winter of 1944-1945 playing in the Cuban League.21 He reported to Braves spring camp in excellent condition and got off to a fast regular-season start. By Memorial Day, his batting average was in the .340 neighborhood. And while he could not sustain that pace, Gillenwater proved more than adequate as a replacement for outfielder Chuck Workman, shifted to third base for the 1945 season.22 Despite a chest injury that put Gilly on the shelf for the last two weeks of the campaign, he posted excellent offensive numbers: .288/7/72, with a .379 on-base percentage and 13 stolen bases. Defensively, he was even better, leading National League outfielders in putouts (451), assists (24), and range factor (3.43). At season’s end, venerable sportswriter Fred Lieb selected Gilly as the center fielder on his major-league rookie all-star team, remarking, “It’s difficult to know what has kept Gillenwater down all this time. As far back as 1941, he was spoken of as another Terry Moore. Gillenwater has the ability to become one of the greatest centerfielders of baseball, and he is no pushover with the bat.”23

Unhappily for Gillenwater, the greatness projected by Lieb never materialized once the end of World War II returned major-league baseball to former competitive norms. Hampered by spring-training blisters, Gilly got off to a slow start in 1946 and was unable to approach his numbers from the year before. In 99 games against vastly upgraded NL pitching, he batted a soft .228, with only one homer and 14 RBIs in 224 at-bats. The ensuing winter, the Braves released Gillenwater outright to their American Association farm club in Milwaukee.24 But eye-catching stats – Gillenwater batted .312 for Milwaukee and led the AA with 23 homers – rekindled Boston interest in him. With the long-quiescent franchise finally back in pennant contention and looking to fortify the roster for the coming 1948 season, the Braves purchased Gillenwater that October.25 Gilly’s return to Boston, however, was blocked by Commissioner A.B. “Happy” Chandler. Given that Gillenwater had been optioned back to the minors by a major-league club three times during his career, Chandler ruled that Gillenwater could not be sold to Boston until he had first been exposed to the minor-league player draft. Because he had not yet been, the Gillenwater sale to Boston was nullified by the commissioner.26

After the ruling, a disappointed Gillenwater asked Chandler to declare him a free agent, but was disappointed by the commissioner there, as well. Stuck in Milwaukee, Gillenwater got off blazing in 1948, hitting .357 in his first 24 games. His reward: another chance in the majors. In mid-May, he was purchased by the Washington Senators for a reported $30,000.27 Playing mostly against left-handed pitchers, he kept hitting as a new American Leaguer, posting a near-.300 batting average until a crop of painful corns on both feet curtailed his appearances.28 Then in August, a pulled leg muscle idled him further.29 Still, his time with the Senators was not without its bright moments. Early in his tenure, Gilly had three hits, a walk, and two RBIs in a May 20 loss to St. Louis, while his 12th-inning home run off Tommy Byrne was the difference in a 2-1 Washington victory over New York on July 2. But as the Senators receded to seventh place in the AL standings, the value to the club of an injury-plagued, 31-year-old part-time outfielder receded with it. At season’s end, Washington traded Gillenwater to the Cincinnati Reds as part of a deal to acquire Clyde Vollmer, a hot prospect with the Reds’ farm club in Syracuse.30

As it turned out, Gillenwatter never played for Cincinnati. He would spend the next five seasons in the outfield of the Syracuse Chiefs. In 335 major-league games spread over five seasons, he had batted a cumulative .260, with only 11 home runs and 114 RBIs, but a positive walks (153) to strikeouts (138) ratio boosted his career on-base percentage to a respectable .359. And he had been an excellent defensive outfielder. All in all, Gillenwater had been a not-quite-good-enough player for a long-term stay in the big leagues. His talents were better suited for the high minors, where he capped off an almost-2,000-game minor league career with a five-year stint in Syracuse that eventually earned him a plaque on the Chiefs’ Wall of Fame.31

After a one-game appearance for Syracuse in 1954, Carden Gillenwater’s final professional season was completed with the Schenectady Blue Jays of the Class A Eastern League. Upon leaving the game, he and his wife settled in Clearwater, Florida, where they operated Gil-Mar Fabrics, a chain of retail fabric and drapery stores. When they retired from the business world some 25 years later, the Gillenwaters devoted themselves to travel and church work. Carden, an avid golfer, also organized local charity golf events.

As he grew elderly, Gillenwater was stricken with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease), an incurable motor neuron disorder that slowly incapacitates its victims. As the end neared, he was placed in Cypress Palms Assisted Living Facility in Largo, Florida.32 He died there on May 10, 2000, three days short of his 83rd birthday. Upon his passing, Marian Gillenwater remembered her husband of 59 years fondly: “It didn’t matter if it was marbles, golf, tennis, or baseball, sports is all he knew. He was a great person, my best friend. Just a real good guy who loved sports.”33 Funeral services were conducted at St. Paul United Methodist Church in Largo, where Gilly had long been a member. His remains were cremated. Survivors included his wife and several nieces and nephews.

Sources

Sources for the biographical info provided herein include the Carden Gillenwater file maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; US Census, Florida city directory, and Gillenwater family data accessed via Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited below, particularly the Gillenwater obituary published in the St. Petersburg Times. Stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 A West Coast columnist once observed that the name Carden Gillenwater “seems like something dreamed up by a perfume salesman.” See “By the Way, with Bill Henry,” Los Angeles Times, July 10, 1948. Actually, our subject’s uncommon first name was his mother’s maiden name. Years later, Carden purportedly maintained, “They named me after my mother because I was the youngest brother of eight and by that time they’d run out of names,” per an unidentified May 1948 news article in the Gillenwater file at the Giamatti Research Center. His surname was most likely Gaelic in origin, Gillenwater being a corruption of O Giollain, taken from the Irish word for lad. See Gillenwater Surname, Family Crest & Coat of Arms on the House of Names website.

2 The older Gillenwater children were Della (born 1894), Alline (1895), William (1897), Karl (1901), Charles (1904), Paul (1906), David (1910), Phillip (1912), and Max (1915). Claral Gillenwater, a five-game pitcher for the 1923 Chicago White Sox, was no relation.

3 As per an unidentified early-1946 profile contained in the Gillenwater file.

4 As recounted decades later in the St. Petersburg Times, May 14, 2000. See also, Baseball Heaven, My Hero: Carden E. (Gilly) Gillenwater, on the LovedOnes/Memorials.com. website.

5 St. Petersburg Times, May 14, 2000.

6 In the questionnaire that he completed for the Hall of Fame library, Gillenwater listed his height as 6’2”.

7 As reported in the (Jersey City) Jersey Journal, September 10, 1938. The surgery was performed at St. Michael’s Hospital.

8 As per the Jersey Journal, August 9, 1938. Rickey reportedly placed a $10,000 sale price on Gillenwater, while simultaneously informing other clubs that neither he nor pitching prospect Ken Raffensberger was for sale.

9 The Sporting News, May 9, 1940.

10 As reported in the Sacramento Bee, September 11, 1940, and newspapers nationwide the following day. In order to make room on the roster for Gillenwater, the Cardinals ended the comeback attempt of one-time star catcher Bill DeLancey, who was made a coach.

11 Columbus sent Gillenwater and pitcher Ed Wissman to Rochester in exchange for pitcher Charlie Brumbeloe and outfielder Augie Bergamo.

12 As reported in the (Little Rock) Arkansas Gazette and New Orleans Times-Picayune, December 17, 1941.

13 As noted in the New Orleans Times-Picayune, March 14, 15, and 19, and June 28, 1942.

14 New Orleans Times-Picayune, May 27, 1943.

15 As reported in the New Orleans Times-Picayune, Omaha World-Herald, and Washington Evening Star, September 19, 1943.

16 See the Macon (Georgia) Telegraph, February 16 and 20, 1944, and Canton (Ohio) Repository, April 10, 1944.

17 New York Times, February 25, 1945. McGowen reported that Gillenwater “was unconscious for nearly half an hour after being carried to the clubhouse.”

18 As per the May 1948 news article cited in endnote 1, above.

19 As reported in the Baton Rouge State Times Advocate, (Boise) Idaho Statesman, and Rockford (Illinois) Morning Star, August 29, 1945, and The Sporting News, September 7, 1945.

20 As reported in the Boston Herald, Chicago Tribune, and New York Times, February 25, 1945.

21 As per The Sporting News, March 8, 1945.

22 In 1944 Workman had batted a mere .208, with 11 home runs and 53 RBIs.

23 The Sporting News, November 1, 1945.

24 As reported in the Chicago Tribune and Dallas Morning News, January 26, 1947.

25 As reported in the Chicago Tribune and Dallas Morning News, October 7, 1947, and Washington Post, October 8, 1947.

26 As reported in the Cleveland Plain Dealer and Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch, October 29, 1947. For more detail on the Chandler ruling in the Gillenwater case, see The Sporting News, October 29, 1947.

27 As reported in the Dallas Morning News, Los Angeles Times, and New York Times, May 13, 1948.

28 As per The Sporting News, July 14, 1948.

29 As reported in the Boston Herald, August 14, 1948.

30 See The Sporting News, October 6, 1948. Commenting upon the transaction, longtime Washington sportswriter Shirley Povich observed that Gillenwater had not been the answer to the Senators’ outfield needs.

31 Gillenwater was posthumously honored by the Syracuse Chiefs in 2004.

32 As per Gillenwater’s obituary in the St. Petersburg Times, May 14, 2000.

33 Ibid. Marian King Gillenwater died at age 87 in 2005.

Full Name

Carden Edison Gillenwater

Born

May 13, 1917 at Riceville, TN (USA)

Died

May 10, 2000 at Largo, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.