Mary Shane

Mary Driscoll was born in Milwaukee and was a member of the baby boom generation. While media descriptions of her would later give an approximate birth year of 1948, based upon a Social Security death index listing and certain inconsistencies in these accounts, it appears that she was actually born on May 17, 1945.

Mary Driscoll was born in Milwaukee and was a member of the baby boom generation. While media descriptions of her would later give an approximate birth year of 1948, based upon a Social Security death index listing and certain inconsistencies in these accounts, it appears that she was actually born on May 17, 1945.

Her father was a former semipro baseball player. By the time Mary was born he was 50 and his playing days were long over, but he continued to coach industrial league baseball. He also imbued his love of the game in his daughter, and Mary’s passion reached new heights when the Braves brought major league baseball to town in 1953: “It was a big occasion when they moved from Boston. I went to the games, sat in the bleachers with my father, waited for autographs.”1 As a result, the girl’s childhood dreams focused around the game.

Mary Driscoll’s earliest ambition was to become a major league second baseman. “I knew it was unheard of then,” she later recalled, “but I thought when I grew up things would change.”2 And like any child, her dreams knew no limitations: “I dreamed of being the best second-base player in the world. In my mind’s eye, I executed that double play over and over again. I dreamed of being a home-run hitter.”3

As Mary grew older, reality forced her to abandon her ambition of playing in the major leagues, but she continued to dream of becoming the Braves’ play-by-play announcer.4 When she graduated from high school and enrolled at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, she had her heart set on majoring in broadcasting and pursuing a career as a sportscaster.

But Mary’s mother advised her to major in “something more sensible. She said [sportscasting] was less common for a girl, and I had to get a real job.”5 At the same time, another aspect of her dream was also succumbing to harsh reality: Milwaukee was on the verge of losing the Braves.

Reluctantly, Mary Driscoll became a history major while also taking journalism courses, with the aim of a teaching career. Soon the young woman who had once dreamed of baseball glory was following a much more conventional life path. She earned her degree from the University of Wisconsin, married a financial consultant named Paul Shane, and accepted a job as a high school history teacher and adviser to the school newspaper.

She and Paul became parents of a son around 1973, and Mary Shane’s dream of a career in baseball must have seemed more remote than ever. But then the sudden death of her sister in a car accident reminded her that life can be cruelly short and led her to reexamine her own life.

Shane came to the realization that she had never lost her love for baseball. Moreover, the supposed security of a teaching career was proving illusory: an oversupply of teachers meant that she had little job security. Coincidentally, the Brewers had brought major league baseball back to Milwaukee in 1970 and Mary Shane decided to pursue her childhood dream of a career in sportscasting. With the support of her husband — “even though,” as she quipped, “he is a football fan” — she quit her teaching position and began doing freelance writing for Milwaukee-area newspapers and magazines.6

In 1975, she applied for a sportscasting job with Milwaukee radio station WRIT and was hired. After waiting expectantly for her first assignment, she recalled, “I was asked to interview the cheerleaders at Marquette University. When they gave me the assignment, my face fell. I couldn’t help it. I was so disappointed. But I did it. And I did the best job I could.” Soon, she was being asked “to cover the Brewers, the Bucks basketball games, and finally the Marquette basketball team — not the cheerleaders.”7

Most of her assignments involved pre-game and post-game reports, which made her gender a significant disadvantage. Access of female reporters to male locker rooms was a controversial topic, as Shane discovered: “Some people were helpful, some were not. I had a couple of rough times. I had to do after-the-game quotes, and the men would keep me waiting outside the locker room for almost two hours while they showered and, I suppose, blow dried their hair. The men were all home and eating dinner by then.” But after deferring her dream for so long, Shane wasn’t going to be put off by another delay: “I waited, I got my story. It wasn’t anything I couldn’t overcome.”8

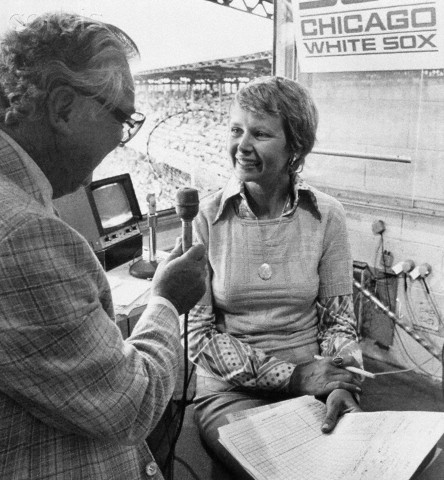

In the summer of 1976, her work brought her to the County Stadium press box for a Brewers game against the visiting White Sox. Sox announcer Harry Caray was surprised to see a young woman in the press box and invited her to do some play-by-play. She did well enough that he asked her to again take the mike the next day and on the Sox’ next visit to County Stadium.

Her appearances caught the attention of the powers-that-be at the Milwaukee Journal and she was offered a job as a sportswriter. Shane accepted, but before she could report for her first day of work, she received a more surprising offer. Charlie Warner, general manager of Chicago’s WMAQ (670), called and asked her if she’d like to join the White Sox broadcast team for the 1977 season.

She was only guaranteed twenty dates in the Sox broadcast booth, which already included Caray, Lorn Brown, and fellow newcomer Jimmy Piersall. Even with the radio and television booths to cover, the position didn’t offer much security. But Mary Shane had already decided that security was an overrated commodity. “I thought for about one split-second,” Shane later recalled, “and said yes.”9

The announcement of her hiring was made in December of 1976 and it attracted widespread attention.10 It was, after all, a historic event. Women had been heard on broadcasts of baseball games as early as 1938, but never before had a woman been hired to do play-by-play for a major league team on a regular basis.11

The media are typically gentle in covering one of their own, and most of the articles about Mary Shane were favorable. But her meteoric rise through the profession also raised questions that also received significant coverage.

Understandably, many accounts focused on her age and lack of experience. Some implied that a man with a comparable background would not have received such an opportunity, while others suggested that it was another stunt by innovative White Sox owner Bill Veeck.

These were legitimate issues, but some of the coverage went still further and appeared to be less about her hiring than the then hot-button topic of women reporters in male locker rooms.12 A UPI piece, for example, informed readers: “A slim, blonde with a soft throaty voice, Mrs. Shane says her sex hasn’t been a big problem in covering sports. She has to wait outside locker rooms to interview most players but Alex Grammas, manager of the Milwaukee Brewers, allows her into his office for post-game interviews.”13 Not only is the description of Shane’s appearance gratuitous, but so was the whole topic of women in locker rooms considering that her new job would have her working in the press box.

But Shane patiently answered all the questions to the best of her ability, knowing all too well that reporters have a job to do and that fielding them was a small price to pay for the chance to fulfill a dream. She took the incessant references to her appearance in stride, joking at one point that she would start her first game by saying, “Hi this is petite, blond Mary Shane, bringing you the White Sox.”14

She was, however, quick to stress that that was just a joke. As she explained to another reporter, one of the burdens of being a pioneer was that she couldn’t afford to joke around: “If the time comes when I’m universally accepted then I can afford to be funny. I think my responsibility is to let people know I do understand the game.”15

She also appreciated that she would be on a very short leash. “Some will be listening very carefully to hear me make a mistake,” she observed, “Some people would be only too happy to say, ‘Sure, you give a woman a chance and she blows it.’ It’s a sobering responsibility.”

But she also expressed confidence that she would be given a fair chance and would win over her critics: “I have found that many people can be won over … if the woman knows what she’s doing. I really can’t afford to make mistakes. I think that’s one of the burdens of doing it. I can’t make the mistakes that men can make … I think it’s extremely important for a woman who has an opportunity like this to do a good job because it can hurt other women. … If I didn’t think I could do it well I wouldn’t have taken it.”16

When asked if she felt that she had gotten special treatment because of her gender, Shane was candid: “Sure, I know being a woman helped, that’s part of it … but in turn I feel the extra responsibility in doing it. And I know when Harry Caray asked me, being a woman may have something to do with it. But if I did a bad job they wouldn’t have asked me back to do it again.”17

Determined to make the most of her opportunity, Mary Shane threw herself into her new job. She quit her job at WRIT and spent the remainder of the winter doing play-by-play on high school basketball games in Milwaukee to familiarize herself with the rhythm and routine of the broadcasting booth.

In February, Mary’s mother moved into her Milwaukee home to help look after her three-year-old son while Mary spent six weeks in Sarasota soaking up the atmosphere of spring training. She took the time to get to know everyone, and attended every practice even though not required to do so. “I don’t want to miss anything,” she explained. “I keep pinching myself to see if I’m really awake. Imagine, me at spring training! I’ve dreamed of this since I was five years old!”18

Jimmy Piersall recalled, “What I remember most about Mary that spring was how hard she worked. I can remember one absolutely awful March afternoon — cold, rainy, everything — she and I were camped out down the left-field line at the Blue Jays’ home park in Dunedin, Florida, working a practice game into a little cassette. I did play-by-play, she did color, but the conditions were totally bush-league, no press box, no heat, no covering from the rain. Still, she pressed on because she wanted to make it so badly.”19

When the season started, initial response was favorable enough that there were reports that other clubs planned to imitate the White Sox’ experiment. The Twins gave a woman named Carol Kerner a chance to work on their broadcasts, and rumor had George Steinbrenner intending to try Pam Boucher on Yankee broadcasts.20

As the weather heated up so did the White Sox, and in early July the surprising club moved into first place in the American League West. With both Chicago clubs atop their divisions, the city’s sports fans were glued to their radios all summer. But by then word had already come down that Mary Shane’s contract was not going to be renewed. And before the season had ended, she had been pulled from White Sox broadcasts altogether.21

What had gone wrong?

Even her defenders concede that Shane had struggled in her new role. Sportswriter Jim O’Donnell saw her as “a victim of inexperience, too much too quickly and no small amount of male resentment,” as well as “an on-air delivery charitably referred to as a ‘high, melodic alto.’”

But her broadcast partner Jimmy Piersall believed that she was also a victim of the fact that Veeck had always been half-hearted toward the idea of a female broadcaster. “She never had a chance,” Piersall recalled. “Even a bad baseball player gets at least one full season to see if he’ll come around. But because of all the in-bred prejudice against a woman covering a baseball team, Mary didn’t even get that. It was a real shame, because I think she had what it takes to make it, and some day the idea of a woman bringing a woman’s perspective to baseball broadcasting will be a tremendous innovation somewhere.”22

With her lifelong dream shattered, Mary Shane could not have been blamed for turning her back on the male-dominated sports world. Instead she chose altering her dream over abandoning it. She and her family moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, where she became a sportswriter for the Worcester Telegram in 1981. She was soon once again breaking barriers, covering the Celtics as one of the few female NBA beat reporters.

Sadly, however, this pioneer was not destined for a long career. Long plagued by heart troubles, on November 1, 1987, Mary Shane died of heart failure at her home in Worcester.23

Sources

Jean Hastings Ardell, Breaking Into Baseball (Southern Illinois University Press, 2005)

Gary Deeb, “Cubs, Sox big winners on TV, too,” Chicago Tribune, July 19, 1977, C1

Richard Dozer, “Sox add woman to radio-TV crew,” Chicago Tribune, December 22, 1976, E4

Paul Giordano, “Baseball opens door for women,” Bucks County Courier Times, January 14, 1977, S2

Carol Kleiman, “Holy cow! She’s made it to the big leagues!,” Chicago Tribune, April 10, 1977, D1

“Milwaukee woman to broadcast Sox games,” AP wire story, Fond du Lac Reporter, January 4, 1977, 16

Peter Morris, A Game of Inches (Ivan R. Dee, 2006)

Jim O’Donnell, “Death stirs memories of broadcast pioneer,” Chicago Daily Herald, November 5, 1987, S5

Clifford Terry, “The mellowing (sort of) of Jimmy Piersall,” Chicago Tribune, June 5, 1977, H22

“Veeck puts femme in radio booth,” UPI: Syracuse Herald-Journal, January 5, 1977, 33

Notes

1 “Milwaukee woman to broadcast Sox games,” AP wire story, Fond du Lac Reporter, January 4, 1977, 16

2 Paul Giordano, “Baseball opens door for women,” Bucks County Courier Times, January 14, 1977, S2

3 Carol Kleiman, “Holy cow! She’s made it to the big leagues!,” Chicago Tribune, April 10, 1977, D1

4 ”Milwaukee woman to broadcast Sox games,” AP wire story, Fond du Lac Reporter, January 4, 1977, 16

5 Giordano.

6 Kleiman.

7 Kleiman.

8 Kleiman.

9 Kleiman.

10 Richard Dozer, “Sox add woman to radio-TV crew,” Chicago Tribune, December 22, 1976, E4. Carol Kleiman, “Holy cow! She’s made it to the big leagues!,” Chicago Tribune, April 10, 1977, D1.

11 Jean Hastings Ardell, Breaking Into Baseball (Southern Illinois University Press, 2005), 202. Peter Morris, A Game of Inches, Volume 2 (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006), 266-67.

12 Ardell, 204-209.

13 ”Veeck puts femme in radio booth,” UPI: Syracuse Herald-Journal, January 5, 1977, 33.

14 Kleiman.

15 Giordano.

16 ”Milwaukee woman to broadcast Sox games,” AP wire story, Fond du Lac Reporter, January 4, 1977, 16

17 Giordano.

18 Kleiman.

19 Jim O’Donnell, “Death stirs memories of broadcast pioneer,” Chicago Daily Herald, November 5, 1987, S5

20 Brainerd [Minnesota] Daily Dispatch, April 14, 1977; Syracuse Herald-Journal, April 19, 1977.

21 Gary Deeb, “Cubs, Sox big winners on TV, too,” Chicago Tribune, July 19, 1977, C1. Jim O’Donnell, “Death stirs memories of broadcast pioneer,” Chicago Daily Herald, November 5, 1987, S5

22 O’Donnell.

23 O’Donnell.

Full Name

Mary Driscoll Shane

Born

May 17, 1945 at Milwaukee, WI (US)

Died

November 1, 1987 at Worcester, MA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.