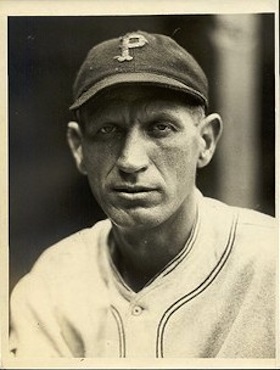

Jewel Ens

The baseball lifer has been around almost as long as the professional game itself. The lifer profile usually begins with a decent, but rarely superabundant, degree of natural playing ability. Thereafter added to the mix are variables like baseball intelligence, leadership skills, a keen eye for judging talent, perseverance, and the ability to function without much public acknowledgment or acclaim. But in the end there is only one indispensible ingredient to achieving lifer status: an abiding passion to remain connected to baseball. Once their playing careers are behind them, those possessing such attributes are prime candidates for scouting, coaching, managing, and front-office positions on both the major- and minor-league level. One lifer who manned all of these posts during his long career in the game is the now largely forgotten Jewel Ens.

The baseball lifer has been around almost as long as the professional game itself. The lifer profile usually begins with a decent, but rarely superabundant, degree of natural playing ability. Thereafter added to the mix are variables like baseball intelligence, leadership skills, a keen eye for judging talent, perseverance, and the ability to function without much public acknowledgment or acclaim. But in the end there is only one indispensible ingredient to achieving lifer status: an abiding passion to remain connected to baseball. Once their playing careers are behind them, those possessing such attributes are prime candidates for scouting, coaching, managing, and front-office positions on both the major- and minor-league level. One lifer who manned all of these posts during his long career in the game is the now largely forgotten Jewel Ens.

Beginning as a teenage infielder in the midlevel minors, Ens gradually ascended, finally assuming the role of major-league utility player, followed by stints as a big-league coach, manager, and scout. He subsequently became a manager in the high minors, ultimately holding the dual job of field skipper-general manager for the Syracuse Chiefs. By the time of his untimely death at age 60, Jewel Ens had logged almost 40 years of uninterrupted service in Organized Baseball.

Jewel Winklemyer Ens was born in St. Louis on August 24, 1889. He was the ninth and final child born to Anton Ens (1846-1910) and his wife, the former Adleheide (Adele) Bartels (1846-1906).1 The parents were Bavarian Catholic immigrants who had settled in St. Louis in 1866. There, Anton supported his ever-growing family by working first as a millwright, thereafter as a sales agent for various local steam-pump manufacturers. According to the 1940 US Census, Jewel finished high school; according to the player questionnaire completed by his son for the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York, Ens had no secondary-school education. Whichever the case, one thing is certain: as a youth, Jewel followed his older brothers onto the sandlots of St. Louis, a turn-of-the-century hotbed for amateur and semipro baseball.2 Primarily an infielder, the righty batting/throwing Ens’s play soon attracted the attention of St. Louis Cardinals scout Jack Ryan. That confirmed in the teenager’s mind the notion that he could make a living playing baseball.

Jewel began his professional career in 1908, signing as a shortstop with the San Antonio Bronchos of the Texas League. But Class C competition proved too fast for the 18-year-old, and after batting .127 (10-for-79, only three extra-base hits) with 14 defensive miscues in 28 games, Ens was released.3 He then returned home to St. Louis and spent the 1909 season playing local semipro ball.4 The following spring, a more physically mature Ens (eventually 5-feet-10½, 165 pounds) proved up to the challenge of Texas League play. Over 134 games about evenly divided between shortstop and third base, Jewel batted .224, with 36 stolen bases,5 for the pennant-winning (82-58) Dallas Giants. The modest BA and a calm, quiet demeanor did little to disguise Ens’s baseball intellect and leadership qualities to observers. In 1911 both Dallas and Jewel would move up, the club being elevated to Class B status, while the now 21-year-old Ens was appointed Dallas field captain. Playing various positions ably (a .941 fielding average spread over 144 games at first base, second, third, and right field), Jewel raised his batting average to .244, with 22 extra-base hits, including the first three home runs of his professional career. He stole 40 bases. Back in Dallas for the third consecutive year, Ens raised both his average (to .270) and his power numbers (38 extra-base hits) in 1912. At season’s end, he received a promotion, drafted by the Providence Grays of the Double-A International League.6

Again, Ens proved unready for a higher level of competition. He hit a disappointing .214 for the Grays, but his defensive versatility proved an asset in a small-roster era. Ens was placed on the club’s reserve list at season’s end, but his days in Providence were numbered. Early into the 1914 season, Ens was demoted, sold to the Chattanooga Lookouts of the Class A Southern Association. There, his batting average revived to .262, with some power (33 extra-base hits). But Ens’s career was headed in the wrong direction. By October he was back in Dallas where he settled in for a five-season run.

Respected and well-liked in Dallas, Ens was greeted with enthusiasm by the locals on his return.7 He responded by playing capably, even breaking the .300 mark in 1918, a season shortened by Jewel’s induction into the US Army.8 Honorably discharged in January 1919, Ens donned his Dallas uniform and batted a respectable .259, with an unexpected 16 homers, that season. But stuck in a Class B minor league and now past age 30, he could not realistically expect that the big leagues were in his future. Ens therefore focused on other ways to stay in the game. In 1920 opportunity presented itself in the form of an offer to become player-manager of a Texas league rival, the Houston Buffaloes. Ens accepted. Regrettably, the Buffs were a sad outfit, covert affiliation with the St. Louis Cardinals notwithstanding. At the close of the season, a 50-101 (.331) record put Houston 59½ games behind Fort Worth in the league standings, and brought Ens’s first chance at managing to an end.

Late in the 1920 season, Ens’s play caught the eye of St. Louis Browns scout Pat Monahan, but the Browns front office declined the $4,000 price tag that Houston placed on purchasing his contract. Then the Cardinals stepped into the breach, acquiring Ens as an offseason insurance policy while third baseman Milt Stock held out. Once Stock signed, Ens became expendable and was optioned to the Syracuse Stars of the International League.9 Back in Double-A ball as a player only, the inexplicable happened. Jewel had a breakout season. He batted .335, with 19 homers among his 59 extra-base hits, for the lowly (64-102) Syracuse club. And for the first time in his 13-year professional career, major-league teams began taking a truly serious interest in Jewel Ens.

Prior to the 1922 season, the Pittsburgh Pirates purchased Ens’s contract from the Cardinals. A 32-year-old rookie, Ens made his major-league debut on April 28, 1922, filling in at second base for an ailing Cotton Tierney. Jewel went 0-for-4 in a 5-3 loss to Cincinnati, but handled four chances flawlessly in the field. The following day he entered the hit column with a single off future Hall of Fame left-hander Eppa Rixey. Ens also stole a base and again played errorless ball in the field during a 7-3 Pittsburgh victory. Thereafter, he served mostly as Tierney’s backup, but also filled in occasionally at the other infield spots. Appearing in 47 games total, Ens batted a solid .296 (42-for-142), with 18 runs scored and 17 RBIs, for the third-place (85-69) Pirates. When not in the lineup, he often manned the third-base coach’s box. All in all, Ens had been a useful addition to the team, and Pittsburgh brought him back for the 1923 season.

For the next three years, Ens was nominally a playing member of the club, but served primarily as a coach for Pirates manager Bill McKechnie. The position was a near-perfect fit for Ens. Pirates players respected his long baseball experience, willingness to assist teammates, and friendly, low-key demeanor, while his insight into game situations, keen powers of observation, and disinclination to call attention to himself made him an asset to McKechnie. As Pittsburgh marched inexorably toward the top of National League standings, Ens received little playing time. In 1923 he saw action in only 12 games, batting .276 (8-for-29). The following season, he was down to five appearances. But a final hurrah awaited Ens. In the second inning of an April 15, 1925, game against Chicago, he blasted a two-run homer off erstwhile teammate Wilbur Cooper. It was his only major-league home run, and the final base hit of Jewel Ens’s four-season playing career. A pinch-running assignment for ejected first baseman George Grantham on June 15 marked the last time that Ens’s name would appear in a major-league box score. For the remainder of the 1925 season, he remained entirely on the coaching lines as the 95-58 Pirates cruised to the pennant. Although technically eligible for World Series play, Ens saw no action in Pittsburgh’s seven-game triumph over the Washington Senators. Still, Jewel Ens could retire from active playing having been a bona fide member of a world championship team. In his time on the Pittsburgh roster, Ens had appeared in only 67 games, but had posted a solid .290 batting mark in limited (54-for-186) at-bats. He had also been a useful infield reserve, and a positive force on the clubhouse.

His playing days behind him, Ens now had to find a way to earn a livelihood. The urgency of the situation increased on November 25, 1925, when Jewel took Mary Elizabeth Campbell (1896-1994) as his bride. In time the couple would have three children: Jewel Jr. (born 1926), Joanne (1929), and James (1933). Happily for the newlyweds, the Pirates were desirous of retaining Jewel’s services, and Ens became a full-time Pittsburgh coach. But the 1926 season proved a disappointment. Beset by injuries, underperformance, and internal strife, the defending world champs finished third, 4½ games behind the pennant-winning St. Louis Cardinals, and the contract of Bucs manager McKechnie was not renewed. His replacement, longtime American League shortstop Donie Bush, retained Ens on the Pittsburgh coaching staff for the coming season,10 a campaign that would see Pie Traynor and the Waner brothers lead the Pirates to another NL crown. Pittsburgh, however, supplied little opposition for the vaunted 1927 New York Yankees of Babe Ruth-Lou Gehrig renown, and was swept in the World Series.

The Pirates continued their erratic path in 1928, falling to fourth place. The following season, the club was back in contention but coming off a bad late-August road trip when skipper Bush abruptly quit. Pittsburgh owner-president Barney Dreyfuss wasted no time appointing coach Ens the new Pirates manager, informing the press, “This is the chance that I have been looking for. I have been watching Ens for a couple of years with the idea that some day, when the chance bobbed up, I would make him the manager. I am not putting him in the job to wind up the year. He is the manager.”11 Taking the reins with his new charges well behind the pennant-bound Chicago Cubs, Ens guided the Bucs to a 21-14 finish and second place in NL standings. A satisfied Dreyfuss thereupon continued Ens as Pittsburgh manager for the 1930 season.

The season would prove a trial for Ens. Injuries to Traynor and Lloyd Waner and a threadbare pitching corps kept the Pirates far off the pace. The club’s final 80-74 log was good for no better than fifth place, leaving Ens’s hold on the manager’s post decidedly tenuous. While the front office decided his fate, Ens and New York Giants coach Dave Bancroft piloted a winter exhibition-game tour of Cuba. When he returned, Jewel was anxious to validate his managerial skills and had the solid support of his players. Then, the signing of former Cubs manager Joe McCarthy by the New York Yankees removed his most formidable rival for the Pirates helm. 12 Ens would be given another chance in 1931. But the third time was not a charm, and Ens was dismissed after piloting the club to a another fifth place (75-79) finish. Although he would remain in the game for another 18 seasons, Jewel would not get another opportunity to manage at the major-league level. He closed the book at 176-167 (.513) for his time as Pirates skipper.

Ens spent the 1932 season as a coach for Bucky Harris, manager of the Detroit Tigers. The club showed dramatic improvement that campaign, posting a 76-75 record that was fully 15 wins better than the previous season’s mark. Thus, Jewel’s discharge from Detroit employ came as a surprise. As observed in The Sporting News, Ens “had a thorough knowledge of the game, was well liked by the Tigers and his work as coach was regarded as satisfactory. When he departed in September to spend the winter in St. Louis, it was though that Jewel would be re-engaged.”13 What followed thereafter was to become a recurring event in Ens’s career. He was immediately hired by a former boss, in this instance Donie Bush, now manager of the Cincinnati Reds. Although engaged as Bush’s subordinate, Ens spent considerable stretches of the 1933 preseason and regular schedule guiding the club while Bush battled various physical and medical problems. And Ens was in charge of the Reds in early June when an on-field brawl with the St. Louis Cardinals precipitated wholesale suspensions by NL President John Heydler, including one imposed on acting field boss Ens.14 Whatever their fighting spirit, the Reds were a bad (58-94) club, finishing in the NL cellar. Manager Bush and his coaching staff, including Jewel Ens, were fired at season’s end.

Another previous boss quickly came to Ens’s rescue. Bill McKechnie, now managing the Boston Braves, added Jewel to his coaching staff for the 1934 season. The following year, Ens returned to Pittsburgh, hired by new Pirates player-manager and longtime friend Pie Traynor. An unidentified 1939 “Thumbnail Sketch” contained in the Ens file at the Giamatti Research Center states that he “was the first man sought by Pie Traynor in his first full season as Pirates manager, and ever since that he has been one of the main props of the Pittsburgh baseball structure. He aids Manager Traynor in all of the club strategy, and as a third base coach he has no superior. [Ens is] recognized everywhere by owners, managers, players and fans as one of the smartest heads in baseball, possessing a vast fund of diamond knowledge.” Jewel suffered along with Traynor when the Pirates lost the 1938 National League pennant to Gabby Hartnett’s storied Homer in the Gloamin’, and was dismissed when new manager Frank Frisch took control of the club a year later.

Once again, the Cincinnati Reds quickly engaged his services. Jewel began the 1940 season as a Reds scout, but was dispatched to Indianapolis in late June to assume command of the Reds’ farm club there. But with the Reds coasting to a second consecutive NL pennant in mid-September, Cincinnati skipper Bill McKechnie had a more pressing assignment for his old third-base coach. He dispatched Ens to scout the Reds’ likely World Series opponent, the Detroit Tigers. And when the Reds prevailed in a close-fought seven-game Series, Ens was among those receiving credit for the triumph.15

Ens spent the remainder of his life in the Cincinnati Reds organization. In 1941 he returned to the coaching lines for the Reds. In the offseason, Cincinnati inked an affiliation agreement with the Syracuse Chiefs of the International League and placed Ens in command of the team. For the next eight seasons, he cultivated prospects for the parent club, winning three IL crowns (1942, 1943, and 1947) in the process. As Ens saw it, his responsibility was twofold: (1) to qualify the Chiefs for the IL playoffs, and (2) “to develop young players into stardom.”16 He was patient with position players and always positive, never hypercritical. With pitchers, he was the same, slow with the hook, preferring that his young hurlers learn to pitch themselves out of tight spots. Among those benefitting from Ens’s tutelage were late 1940s Reds pitching ace Ewell Blackwell and, particularly, future National League MVP Hank Sauer, who credited Jewel with teaching him to curb his temper and molding him into an adequate defensive outfielder.

In 1949 Ens added general manager duties into his portfolio of Syracuse responsibilities. That season the Chiefs finished 73-80 and did not make the IL playoffs. GM-manager Ens immediately set about rebuilding his team, but was hampered by a nagging cold that he caught in early winter. By the time Ens obtained medical help, reputedly the first time that had seen a doctor in 25 years, pneumonia had set in. He was admitted to University Hospital in Syracuse, but his condition only worsened. Then, an aortic aneurism was discovered. A rupture during emergency surgery brought the life of Jewel Ens to its close on January 17, 1950. He was 60. After a viewing in Syracuse, the body was brought home to St. Louis for a Funeral Mass at St. Ann’s Church.17 Interment was at Memorial Park Cemetery in nearby Jennings, Missouri. Survivors included his wife, Mary Elizabeth; children Jewel Jr., Joanne, and James; his brothers Charles, Otto, and Mutz; and his sister, Bertha Ens Poetting.

In the months after his death, Jewel Ens was elected to the International League Hall of Fame. In 1964 he was selected as manager of the all-time Syracuse Chiefs team, and in 2000 a plaque in Ens’s memory was placed on the Syracuse Chiefs Wall of Fame – all fitting tributes to a baseball lifer who dedicated more than 40 years to the game.

Sources

Sources for the biographical information provided herein include the Jewel Ens file, with player questionnaire completed posthumously by his son Jewel, Jr., maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; Ens family info posted on Ancestry.com, and various of the newspaper articles cited below, particularly the Jewel Ens obituaries published in the Syracuse Herald Journal, January 18, 1950, and The Sporting News, January 25, 1950. Unless otherwise noted, statistics have been taken from Baseball-Reference.com. and/or the player transaction cards contained in the Ens file at the GRC.

Notes

1 Jewel’s elder siblings were Bertha and Sophia (born 1871), William (1875), Emil (1878), Charles (1882), Emma (1883), Otto (sometimes given as Adolph, 1885), and Mutz (Anton, 1887).

2 Emil Ens later became a groundskeeper at Sportsman’s Park, while brothers Charley and Mutz played minor-league baseball. Mutz was also a three-game first baseman for the 1912 Chicago White Sox.

3 Baseball-Reference indicates that Ens was also a member of the Texas League Shreveport Pirates during the 1908 season, but the writer could find no stats for Ens with that club.

4 As per the Ens obituary in The Sporting News, January 25, 1950.

5 His stolen base total is taken from the 1911 Reach Guide.

6 As reported in Sporting Life, October 5, 1912. The draft price for Ens was $750.

7 As noted in Sporting Life, December 5, 1914.

8 Jewel and older brother Mutz served together in a St. Louis depot brigade.

9 For more detail on these events, see “Ens Entered the Majors and Couldn’t Get Out,” an unidentified January 30, 1930, news article contained in the Jewel Ens file at the Giamatti Research Center.

10 As noted in the Evansville (Indiana) Courier and Press and Zanesville (Ohio) Independent, December 1, 1926, and elsewhere.

11 As subsequently related by sportswriter Frank Graham in the New York Sun, May 7, 1930.

12 See “Chance to Vindicate Self, Desire of Ens,” The Sporting News, October 23, 1930.

13 From “Ens Not to Return as Aide to Harris; Release of Former Pirate Comes as Surprise,” The Sporting News, November 24, 1932.

14 As reported in the Dallas Morning News and Van Wert (Ohio) Daily Bulletin, June 8, 1933, and elsewhere.

15 See, e.g., “Jewel Ens Was Great Help to Reds in Recent World Series,” Charleroi (Pennsylvania) Mail, October 23, 1940.

16 Syracuse Herald Journal, January 18, 1950.

17 As per The Sporting News, January 25, 1950.

Full Name

Jewel Winklemyer Ens

Born

August 24, 1889 at St. Louis, MO (US)

Died

January 17, 1950 at Syracuse, NY (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.