Steve Gromek

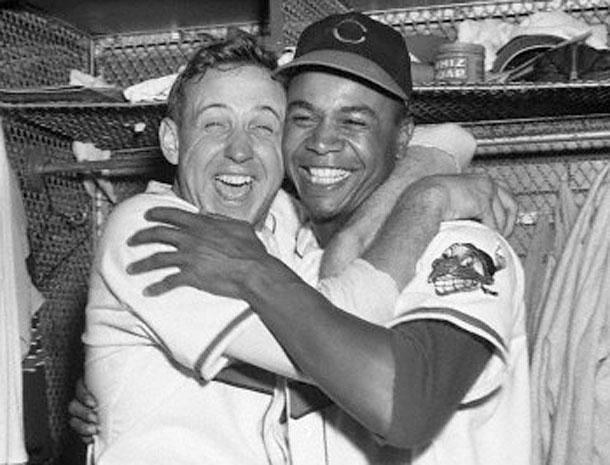

Few Americans had ever seen anything like it — a black man and a white man cheek to cheek. The image greeted readers of many sports pages across the country on the morning after Game Four of the 1948 World Series: the winning pitcher, Steve Gromek, hugging Larry Doby, whose home run was the victory margin in the 2-1 game, both men grinning like fools.

Few Americans had ever seen anything like it — a black man and a white man cheek to cheek. The image greeted readers of many sports pages across the country on the morning after Game Four of the 1948 World Series: the winning pitcher, Steve Gromek, hugging Larry Doby, whose home run was the victory margin in the 2-1 game, both men grinning like fools.

Gromek, the white man, remembered the reaction when he went home to Hamtramck, Michigan, and walked into his neighborhood bar: “I saw a guy I had known for more than 10 years, a guy I had played ball with. I said hello, and he ignored me.” The bartender told Gromek, “‘Oh, Christ, it’s that picture you took with Larry Doby.’ … So then the guy told me, ‘Jesus, you could have just shook his hand.’ But then this other friend of mine says, ‘If I was in Steve’s shoes, and Doby did what he did, I would have kissed him.’”

Doby cherished the photograph for the rest of his life. “The picture was more rewarding and happy for me than actually hitting that home run,” he said.1

In the second year since Jackie Robinson and Doby integrated major-league baseball, writers saw the photo as a moment dripping with symbolism. Gromek and Doby both said it was the most natural thing in the world: two teammates united in celebration.

While Doby stood out because of his color — he and Satchel Paige were the only black players in the Series — Gromek was nearly invisible on the 1948 Indians. Once a phenom compared to Bob Feller, he was eclipsed by the Indians’ new pitching stars after World War II. Baseball’s reserve clause held him hostage in Cleveland as his prime years slipped away.

Steven Joseph Gromek was born in Hamtramck on January 15, 1920, the first child of the former Jozepha Openchowska and Ignatius Adam Gromek, a factory worker. Both parents were Polish immigrants, and their hometown, a tiny enclave surrounded by Detroit, was populated by thousands of their countrymen.

St. Ladislaus High School couldn’t afford a baseball team or a coach, so one of the priests put 15-year-old Steve in charge of the softball and basketball programs. The boy played baseball on neighborhood lots, often staying out until after dinnertime and earning a clout on the ear from his mother. Detroit Tigers scout Wish Egan, watching him play shortstop in American Legion ball, pronounced him too frail at 6-foot-1 and 145 pounds. But the day Cleveland scout Bill Bradley was in the stands, Gromek smacked two hard line drives off the city’s premier teenage prospect, Hal Newhouser. Bradley signed him for the Indians.

The 19-year-old played second base and shortstop in 1939 for Class-D clubs in Logan, West Virginia, and Mansfield, Ohio. He strained his left (non-throwing) shoulder on a hard swing late in the season. When the injury didn’t heal, he began switch-hitting to ease the stress on the shoulder. He was playing close to home at Class-C Flint, Michigan, in 1940, still hurting and not hitting. Manager Jack Knight took note of his strong throwing arm and tried him out as a pitcher.

The position change saved his career. He went 4-0, allowing just five runs in 28 innings. Back in Flint the next year, he won 14 straight before the Indians summoned him to the majors in August. The American League proved tougher than the Michigan State circuit. Quaking in his spikes, Gromek surrendered four runs in four innings in his debut on August 8, a 4-2 loss to the Senators. He started once more, on August 27 against the Athletics, and staggered to his first victory while giving up 11 hits.

It took two more years before Gromek stuck with the Indians in 1944, when rosters were depleted by war. He was draft-deferred because he was the sole support of his family. His father was disabled by rheumatism, and his younger sister had a chronic illness.

He spent the first half of the season in the bullpen before he got a chance to start regularly in July. Twice he took no-hitters into the eighth inning, and on July 25 he struck out 10 Yankees to record his first shutout. The Cleveland Plain Dealer’s Gordon Cobbledick hailed him as “the greatest young pitcher to hit the big leagues since Bob Feller.”2 The writer described the blond 24-year-old as “what your mother used to call ‘a nice looking boy’ [and] ‘a good boy.’”3

Filled out to around 180 pounds, Gromek had converted to a sidearm motion because it gave him more movement on his fastball. With flamethrowers Feller and Tex Hughson gone to military service, an unidentified umpire called him the hardest thrower in the league with a fastball that appeared to rise six inches.4 He won six straight decisions late in the season to finish at 10-9, 2.56, while holding opposing hitters to a .219 batting average.

His success carried over into 1945. After he won seven of his first eight decisions, The Sporting News named him Player of the Week. He won his 12th on August 1 and appeared to have an easy shot at 20 victories. But on the 26th he scored the game-winning run by hurdling over Detroit catcher Bob Swift. Gromek paid for it with a twisted left knee that limited him to one start in the next two weeks. His bid for his 20th win on the season’s final day was nullified when rain washed out the game in the fifth inning. He wound up at 19-9, 2.55, ranking in the league’s top 10 in ERA, strikeout/walk ratio, and fewest base runners (WHIP).

Gromek married Jeanette Kayko after the season. Although the achievements of wartime players were generally suspect, Cleveland News writer Ed McAuley projected that the Indians would have one of the league’s strongest starting quartets in 1946 with Gromek and Allie Reynolds joined by returning servicemen Feller and Red Embree.5

But Gromek acknowledged that he reported to spring training overweight and never found his footing. With his ERA around 4.50 in August, he was pulled from the rotation. He dragged to the finish line with a 5-15, 4.33 record, looking like just another overmatched wartime replacement.

At the end of the season Gromek almost escaped Cleveland for the Promised Land. The Indians, looking to acquire second baseman Joe Gordon from the Yankees, offered New York a choice of Gromek, Embree, or Reynolds. Yankees president Larry MacPhail consulted his star, Joe DiMaggio, and DiMaggio recommended Reynolds, who became a mainstay of the pinstripe dynasty.6

Stuck in Cleveland, Gromek was filed and forgotten. After he suffered another knee injury in the spring of 1947, manager Lou Boudreau parked him in the bullpen and seldom used him. In only 84 1/3 innings, he went 3-5, 3.74. At the end of the lost season, owner Bill Veeck cut his salary by $2,500, but promised him a bonus if he had a big year in 1948.

Not much chance of that. The Indians were assembling a new pitching staff around Feller. Converted outfielder Bob Lemon joined the rotation in 1947, and rookie knuckleballer Gene Bearden was the phenom of 1948. Boudreau had lost confidence in Gromek, partly because he considered the right-hander a one-pitch pitcher. “I had a good rising fastball but not much of a curve,” Gromek said. “Boudreau told me he’d fine me $250 if I ever threw a curve.”7

He was working on what he called a “curving knuckleball.” He had plenty of time to experiment during another year as a mop-up reliever. He started just nine games, most of them in doubleheaders when Boudreau needed an extra arm.

The 1948 Indians were locked in one of the tightest pennant races in history. On August 3 the top four teams — Cleveland, New York, Boston, and Philadelphia — were separated by only .006 in the standings. Gromek pitched his best game of the year in the second game of a Sunday doubleheader on September 19, shutting out the Athletics on three hits. The victory pulled the Indians up to ½ game behind the first-place Red Sox.

Gromek was outstanding in his limited opportunities — 9-3, 2.84 — but he didn’t start again. Boudreau relied on aces Feller, Lemon, and Bearden down the stretch. Boston and Cleveland finished in a tie, and the Indians claimed the pennant in a playoff.

In the World Series against the Boston Braves, Boudreau ran out the Big Three to win two of the first three games. But he had never settled on a fourth starter. Rather than bring Feller back on two days’ rest, he gave the ball to spare-part Gromek for Game Four. “I almost fell off my chair,” the surprised pitcher said.8 He hadn’t started in nearly three weeks and had told his parents that he probably wouldn’t pitch in the Series.

“The way Boudreau explained it was, ‘I’m willing to sacrifice and pitch Gromek, then come back with Feller,’” Gromek recalled, adding, “I knew it wasn’t a compliment. What it did was motivate me.”9 Before a record baseball crowd of 81,897 in Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium, he pitched shutout ball through six innings, allowing only four hits. Boudreau doubled home a run in the first, and Doby’s homer in the third made the score 2-0.

Boston’s Marv Rickert led off the seventh with a homer to cut the lead to a single run. Gromek held it the rest of the way. Finishing strong, he got his only two strikeouts in the ninth, then retired pinch-hitter Bill Salkeld on a fly to right to nail down the biggest victory of his life. Typical for Gromek, the game took just one hour and 31 minutes, and he threw only 98 pitches.

Photographers in the clubhouse captured his joyful hug with Doby. Gromek’s performance gave Cleveland a 3-1 edge in the Series and set up the Big Three to finish it on normal rest. After Feller lost the next day, Lemon and Bearden combined to clinch the championship in Game Six.

A few weeks later, Bill Veeck called to tell Gromek a bonus check was in the mail. It was for $5,000, twice the amount of his pay cut. “I told him he was a real Santa Claus.”10 Steve and Jeanette used the bonus, plus his record $6,772 Series share, to buy their first home. Their first child, Carl, had been born before the season.

Veeck predicted that Gromek would be Cleveland’s top pitcher in 1949. But during the offseason the Indians acquired Early Wynn from Washington. He and rookie Mike Garcia joined Feller and Lemon in the rotation as Bearden turned out to be a one-year wonder. As far as Boudreau was concerned, Gromek was typecast as a second-stringer. He started just 12 times, working 92 innings. “Steve didn’t start enough to work up a good sweat,” Ed McAuley wrote.11

And so it went for the next three years. Buried in the shadow of those stars, Gromek passed his 30th birthday in a dreary routine: a dozen or so starts, a few more relief appearances, never more than 123 innings in a season. It’s not that he was a lousy pitcher. By the end of 1952 he had compiled a career 3.22 ERA, 11 percent better than average, and a 77-66 record. Opponents batted only .239 against him.

It was no disgrace to be a spear-carrier for three future Hall of Famers — Feller, Wynn, and Lemon — and Garcia, who was as effective as his famous mates for a few years. The Indians settled into a perennial second place behind the Yankees. Every year they seemed to believe that they would ride their Big Four pitchers to the top.

Gromek’s name was seldom mentioned in trade rumors. Other teams may have accepted Cleveland’s judgment that he was second-rate. He was not good enough to crack the Indians’ rotation, but too good to trade away for nothing.

Liberation Day came on June 15, 1953, when Cleveland swapped Gromek, shortstop Ray Boone, and pitchers Al Aber and Dick Weik to Detroit for right-hander Art Houtteman, lefty Bill Wight, catcher Joe Ginsberg, and infielder Owen Friend. Heading back to his hometown, the 33-year-old Gromek said, “It’s like starting over. I’m a rookie again.”12

The Tigers had finished last the year before and were on their way to a third straight losing season with the league’s worst pitching and defense. In his first start, Gromek shut out Philadelphia on four hits to earn a spot in the rotation, but the results were uneven. He finished with a 4.51 ERA and 6-8 record with Detroit.

As the Tigers’ Opening Day starter in 1954, Gromek pitched a four-hit shutout to beat Baltimore. He struck out nine using a new sinker that broke like a screwball. (Maybe it was a sinker; Sport magazine named Gromek, without evidence, as one of several pitchers suspected of throwing a spitball.)13 He won his first five starts, all complete games, and pitched 29 consecutive innings without issuing a base on balls.

Gromek and the Tigers were involved in the season’s biggest brawl on Sunday, August 29, in Philadelphia. The trouble started the previous Friday night, when the Athletics’ Marion Fricano beaned Cass Michaels of the White Sox, sending him to a hospital with a fractured skull. Michaels, a Detroiter, was a friend of Gromek’s and several other Tigers. When Fricano relieved in Sunday’s game, Detroit’s Harvey Kuenn thought the pitcher threw at him. It took all four umpires to hold Kuenn back.

Fricano came to bat in the next inning, and Gromek knocked him down. When Gromek’s turn at the plate came in the ninth, Fricano hit him in the back. Gromek charged the mound, waving his bat, then dropped the weapon and the two pitchers wrestled each other to the ground as their teammates rushed the field in an all-out donnybrook. Gromek emerged from the scrum with his shirt shredded.14 He was fined $100, and Fricano was fined $150 and warned about throwing at hitters. (The beaning ended Michaels’ career.)

Gromek was the ace of a losing team. The Tigers were shut out in four of his starts, and he lost other games by 2-1, 3-1, and 3-2. He finished 18-16, 2.74, in a career-high 252 2/3 innings. The only warning sign: He served up 26 home runs, most in the league.

His second chance had come too late. After a strong start in 1955, the 35-year-old Gromek began fighting back problems that forced him to miss several turns. His second half was a disaster as he tried to pitch though the pain, and he was shut down two weeks before the end of the season. Although he finished 13-10, 3.98, the home-run balls came even more frequently; he gave up 26 homers in 181 innings.

The Tigers had developed several rising young pitchers, including Frank Lary, Paul Foytack, and Billy Hoeft, so Gromek spent most of 1956 in the bullpen. His back flared up again the next year, and he appeared in only 15 games before he announced his retirement in August.

Detroit hired him to manage its Class-D club in Erie, Pennsylvania, in 1958. He worked another year for the team as a scout, conducting tryout camps, then began selling insurance for the Automobile Club of Michigan.

The Gromeks’ youngest son, Brian, collapsed during high school baseball practice and died of a cerebral hemorrhage at 16. Sons Carl and Gregory played baseball at Florida State. The Tigers drafted Gregory in the 34th round in 1971 as a shortstop. Like his father, he converted to pitching, and played for four years, rising as high as Double A.

Gromek served as commissioner of the Pony/Colt youth league in suburban Birmingham, where games were played on Brian Gromek Memorial Field. Steve Gromek died at 82 on March 12, 2002.

Photo credit

Cleveland Plain Dealer

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Stephen Glotfelty.

Notes

1 Joseph Thomas Moore, Pride Against Prejudice: The Biography of Larry Doby (New York: Praeger, 1988), 3-4.

2 Gordon Cobbledick, “Gromek’s Two-Hit Pitching Nullified by Errors, Red Sox Win, 1-0,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 1, 1944: 12.

3 Cobbledick, “Plain Dealing,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 3, 1944: 14.

4 Shirley Povich, “Umps Call the Hop on A.L. Pitchers,” The Sporting News (hereafter TSN), August 17, 1944: 10.

5 Ed McAuley, “Cleveland Indians,” TSN, April 18, 1946: 5.

6 Dan Daniel, “Gordon Reveals Rows With MacPhail,” TSN, May 28, 1947: 3.

7 Bob Dolgan, “A Racial Milestone,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 26, 1998: 10-C.

8 Ibid.

9 Russell Schneider, Amazing Tales from the Cleveland Indians Dugout (Kingston, New York: Sports Publishing, 2017), 93.

10 Paul Dickson, Bill Veeck, Baseball’s Greatest Maverick (New York: Walker, 2012), 161.

11 McAuley, “Indians a Vanished Tribe, Without ’48 Zip,” TSN, October 5, 1949: 12.

12 “Shift to Tigers Satisfies Steve,” Detroit Free Press, June 17, 1953: 25.

13 Milton Gross, “Are They Still Throwing the Spitter?” Sport, October 1956, 28.

14 Art Morrow, “Tigers Rout A’s, 14-3, 2-1, Amid Fight Over Beanball,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 30, 1954: 18-19.

Full Name

Stephen Joseph Gromek

Born

January 15, 1920 at Hamtramck, MI (USA)

Died

March 12, 2002 at Clinton Twp; Macomb County, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.