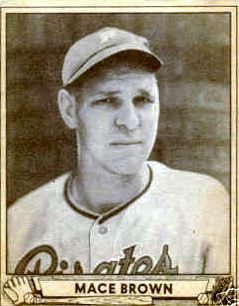

Mace Brown

Mace Stanley Brown was on the leading edge of early relief pitching specialists that began to emerge in the game in the 1930s. The right-hander enjoyed a Major League career that spanned eleven years and three teams but, despite an All-Star game appearance in 1938 and service in the U.S. Navy in 1944-1945, he is best remembered for offering up the pitch in 1938 that became Gabby Hartnett’s “Homer in the Gloamin’.”

Mace Stanley Brown was on the leading edge of early relief pitching specialists that began to emerge in the game in the 1930s. The right-hander enjoyed a Major League career that spanned eleven years and three teams but, despite an All-Star game appearance in 1938 and service in the U.S. Navy in 1944-1945, he is best remembered for offering up the pitch in 1938 that became Gabby Hartnett’s “Homer in the Gloamin’.”

Born May 21, 1909, on a farm just outside North English, Iowa, to Gary (a school janitor) and Justine Brown, Mace had to confine his high school athletic accomplishments to the track oval, not the baseball diamond. His high school did not field a baseball team so, although Brown caught for the town team during the summer, he threw the javelin for his alma mater. His arm earned him a track scholarship to the University of Iowa in 1927.

Persistent presence at the baseball field caught the attention of the Iowa coach, Otto Vogel, who after giving the boy a tryout, put him on a baseball scholarship. He played catcher in 1928, his sophomore year, but in 1929 Vogel moved him to the pitching mound. After using his natural curveball to blank Rice Institute (now Rice University) 6-0, he played one final game behind the plate before becoming a full-time pitcher. Despite his shutout of Indiana in the last game of the season, culminating in a 9-1 record with two saves for Brown, the 21-10 Hawkeyes lost the Big-10 title by one-half game to Michigan.1

That summer, after his junior year, Brown pitched semi-pro ball for a team from Marshall, Minnesota, of the Southern Minnesota League. By accepting money, he forfeited his amateur status and became ineligible for further competition in college baseball. Brown opted not to return to the university to finish college, instead signing with the Cardinals’ organization in 1930. For four years Brown endured an exhausting series of career promotions with stops in towns like Greensboro and Durham, North Carolina; Shawnee, Kansas; Des Moines; and Tulsa.

The time was well spent on the diamond, and invaluable for his personal life. In 1930, he married Susan Vaughn Talley, from Durham. She would be his companion for the next 69 years. The couple had two children, a son, Al, and a daughter, Carolyn, and they ultimately led to five grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren.

It was at Tulsa, however, that his talent finally earned a serious look from the major leagues. His 19 wins and 3.53 earned run average for a Class A minor league affiliate of the Pittsburgh Pirates caught the attention of the latter’s front office, and the major league team signed him after the 1934 season.

On May 21, 1935, his twenty-sixth birthday, Brown made his big league debut for the Pirates, and over the remainder of the season won four games in eighteen appearances. He won seventeen games between 1936 and 1937, achieving an ERA of 4.00, and notched ten saves (awarded retroactively since saves were not recorded as an official statistic until 1969) in the span. It was 1938, however, when Mace earned a tiny share of immortality.

The 1938 season was perhaps Mace Brown’s finest campaign. That year he led the Pirates with fifteen wins, buttressed with five saves (awarded retroactively) and a 3.80 ERA, in a league-leading fifty-one appearances. Brown’s efforts landed him a roster spot on the 1938 National League All-Star team, and he pitched the final three innings of a 4-1 NL victory.

Supported, in part, by Brown’s prowess — at the end of the year, he would finish ninth in National League MVP voting – the Pirates entered the last days of the season leading the NL pennant race by 1 1/2 games. On September 27, the Cubs won to close to one-half game behind first place Pittsburgh, and after eight innings the next afternoon the teams were deadlocked in a game at 5-5. Umpire Jocko Conlan, upon deliberating with his crew after watching the late day sky darken as the inning ended, announced that the game would end after nine innings, regardless of the score. If necessary, it was assumed, the teams could play a doubleheader the next day.

In the fading daylight, the “Gloamin’,” with two out in the bottom of the ninth inning at Wrigley Field, Brown set up the Cub catcher, Gabby Hartnett, with two curves for strikes. “I got him strike one, then a foul ball for strike two, both curves,” Brown recalled in an interview for Pen Men.2 “When he was swinging at one of them, he just looked like a schoolboy, and I said to myself, ‘I’ll just throw him a better one and strike him out.’ Well, I just made a lousy pitch. He hit it to left center up into the seats. I didn’t follow it into the darkness. I knew it was gone.”

Hartnett’s blow ultimately propelled the Cubs into the World Series, and both pitcher and hitter irrevocably into baseball lore. The homer was Homeric, an improbable hit under the circumstances, and the surrounding mythology has only congealed with time. Brown later told George Wine, “Gabby must have swung at what he heard, because it was too dark for him to see the ball.”3

The next two seasons passed quietly. During the span, Brown appeared in 95 games for the Pirates, a mix of starts and relief appearances, yet managed to keep his ERA below 4.00. In 1941, after he’d pitched only one and one-third innings during the young season, the Pirates sold Brown’s contract to the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 22. The reliever did not start a game all year, but did pick up three saves (awarded retroactively) for his new team. In August Brooklyn loaned him to the Cubs’ farm club in Los Angeles, and he was sold to the Boston Red Sox in December.

He pitched well in 1942 and 1943, leading the American League with 49 appearances in 1943, although admittedly against war-depleted rosters, but in 1944 he joined the fight by accepting a commission as a Lieutenant, Junior Grade, in the United States Navy. Sworn in at Raleigh, North Carolina, he reported to the Norfolk Naval Training Station, where he pitched for the base team. He remained in Virginia until the following March, when he was transferred to a Naval Air Station in Hawaii, under the guise of “morale improvement,” and from there was sent to Guam where he served with the Marine Corps Island Command. Duties included touring the Western Pacific Theater with the Navy’s all-star team.4

On January 6, 1946, he was discharged from the Navy. He worked to return to a modicum of baseball conditioning, but at age 36, it was an insurmountable challenge. A nagging spring training elbow injury limited him to eighteen appearances for the Red Sox that season, and on September 10 he pitched in his final regular season game. In his one inning of World Series work, he gave up four hits and three runs to the Cardinals.5 Less than a month later, on October 29, Boston released “number 25” and, soon thereafter, Brown retired as a player.

Overall, he posted a respectable career record of 76-57, with a lifetime ERA of 3.46 over 1075 innings. It was his ground-breaking work as a relief specialist, recorded in his 48 career saves (awarded retroactively), which made him unique among his peers. Of the 387 games in which he appeared, he started only 55, yet pitched well enough to remain employed by various teams for over a decade. By the end of his career, his annual salary approached $12,000.

Despite retiring as an active player, Brown remained in baseball. The next season, 1947, Mace signed on as a scout and instructor with the Red Sox. He remained in that capacity for eighteen years, finally joining the major league club’s coaching staff for the 1965 season. The next year, at age 57, he returned to full-time scouting for Boston, a job he retained until 1979, when he reduced his role to that of consulting. At Sue’s insistence, he finally retired for good in 1989. Among the players scouted by Brown, his most notable discovery was South Carolina slugger Jim Rice, who signed with Boston after being drafted in the first round in 1971.

Now out of the game, Mace and Sue spent the next decade living quietly in their home on Holden Road in Greensboro. He liked to watch the Braves on television, and would sign the regular autograph requests that came his way. “Mace would get five or six items every week that people would send to be autographed,” said Charles Qualls, a former Greensboro resident who now lives in Atlanta. “He signed every last one of them. He told me, ‘I guess it’s because I gave up that home run.’”6

On January 26, 2000, his wife of 69 years, Sue, died in North Carolina. From that day on, big-hearted Mace was cared for and accompanied in his home by his daughter Carolyn until passing away on March 24, 2002, at the age of 92. His funeral was held two days later at the Grace United Methodist Church in Greensboro.

Mace Brown was buried in his Red Sox uniform at the Westminster Gardens Cemetery in Glenwood, North Carolina.

Notes

1 Wine, George. “Honoring Mace Brown” English Valley’s Alumni Online, 2002. http://showcase.netins.net/web/evonline/honoringalumni.html.

2 Cairns, Bob. Pen Men. St Martin’s Press, 1992.

3 Wine.

4 Bedingfield, G. Baseball in Wartime web site.

http://www.baseballinwartime.co.uk/player_biographies/brown_mace.htm.

5 Baseball-Reference.com.

6 Haas, W. KIND-HEARTED MACE BROWN THREW MEAN CURVE; THE FORMER PITCHER, WHO DIED SUNDAY AT 92, MADE TIME FOR FAMILY AND FRIENDS IN HIS MORE THAN 60 YEARS IN BASEBALL. The News & Record (Piedmont Triad, NC). March 26, 2002.

Full Name

Mace Stanley Brown

Born

May 21, 1909 at North English, IA (USA)

Died

March 24, 2002 at Greensboro, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.