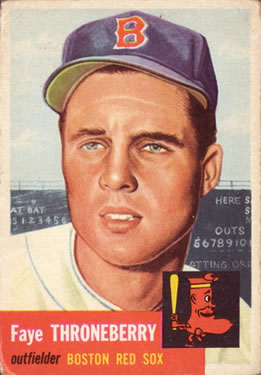

Faye Throneberry

Maynard Faye Throneberry was the decidedly less-colorful — and less-celebrated — of the major leagues’ two Throneberry brothers. His younger brother was dubbed “Marvelous Marv”, a player who gained infamy as a symbol of baseball ineptitude, particularly in the field and on the base paths. Faye (he was never referred to by his first name) was coldly profiled by Washington Post columnist Bob Addie as “the Calvin Coolidge of baseball… a reticent young man who feels cheated if he can’t answer every question with ‘yes’ or ‘no.’”1 Addie’s colleague at the Post, the legendary Shirley Povich, agreed; painting Faye as “workmanlike…less than highly exciting.”2

Maynard Faye Throneberry was the decidedly less-colorful — and less-celebrated — of the major leagues’ two Throneberry brothers. His younger brother was dubbed “Marvelous Marv”, a player who gained infamy as a symbol of baseball ineptitude, particularly in the field and on the base paths. Faye (he was never referred to by his first name) was coldly profiled by Washington Post columnist Bob Addie as “the Calvin Coolidge of baseball… a reticent young man who feels cheated if he can’t answer every question with ‘yes’ or ‘no.’”1 Addie’s colleague at the Post, the legendary Shirley Povich, agreed; painting Faye as “workmanlike…less than highly exciting.”2

Born of German-Irish descent in Fisherville, Tennessee, a rural community about 22 miles east of Memphis, on June 22, 1931, Faye was raised in nearby Collierville with his brother Marv, born two years later. A far better athlete than student — he was held back twice in grade school and eventually dropped out of Collierville High School two years before his scheduled graduation — Faye batted nearly .500 for the high-school baseball team. Moving on to play American Legion ball with the Corbitt Motors team after leaving high school, Faye batted a reported .480 there. By early 1950, he was being heavily courted by big-league scouts.3

Maynard Faye and Marvin Eugene Throneberry’s parents were Walter Hugh Throneberry (1902-1946) and Mary Alice Callicut or possibly Callicutt (1903-1993). Theirs was a farming family; as of the 1920 census, Walter Throneberry worked on his father’s farm. Walter and Mary Alice were married in 1922. Faye and Marv had an older brother, Walter (1923-2000).4

Detroit Tigers scout Howard Camp made the best offer, and on March 18, 1950, Faye Throneberry signed with Camp. Less than a month later, Baseball Commissioner Happy Chandler ruled the contract invalid, in violation of the prevailing rule. The 18-year-old Throneberry was ineligible to sign a professional baseball contract until June 4, “the day after the original class with which he entered High School graduates…and after clubs have been bulletined with respect to his eligibility.”5 Apparently, Mary Throneberry, anxious for the bonus money, advised Camp that “Faye should have graduated from Collierville High School in the Class of June 1949,” taking into account that Faye was two years behind his classmates. 6 Chandler disagreed.

Instead, Faye signed with scout George Digby of the Boston Red Sox in June. “[T]he Yankees made me a very nice offer, but I thought the Red Sox’ offer was just a little bit better,” Faye told the United Press. “Also, the Yankees then had a very, very good outfield and I figured I might have a better chance making the Sox.”7 Boston sent Throneberry to the Single-A Scranton Miners for the next two years. After a modest rookie season in 1950 (.263 with five home runs), he prospered in 1951, blasting 13 home runs and legging out 10 triples, to go along with a .304 batting average for the Eastern League club. Faye was one inch less than six feet tall, with a playing weight of 185 pounds. He batted left-handed and threw right-handed. It was his hitting that won him all the accolades. Grounders “went through him like sand escaping an enlarged sieve,” a sportswriter commented, and fly balls were never routine, either. 8

Throneberry had a productive January 1952, highlighted by his marrying the former Peggy Bobbitt on the 12th. He did not have much time to celebrate, as he had to report to a special early training camp held by the Red Sox in Sarasota, Florida. This camp was designed to “help talented youngsters skip a [minor league] classification on their way to the majors.” Along with Faye at Sarasota were more than 30 other rookies including Dick Gernert, Gene Stephens, and Ted Lepcio.9

Faye greatly benefitted from the early camp. By the time regular Red Sox players reported to Florida in March, he was in top shape. During an early Grapefruit League contest, at least one onlooker was heard to comment, “There’s your new [Enos] Country Slaughter” after watching “the Collierville Flash” in action for just a few innings.10 In an exhibition game against the Yankees, Faye’s snare of a New York drive to deep center field was tagged, “one of the fanciest catches of the Florida season.” 11 Casey Stengel raved, “Now there’s a kid who will make it. There’s a natural-born player. I wish we could have got him….He can really get on his horse.”12 Throneberry also starred in the annual pre-season City Series with the Boston Braves, helping him secure a spot on the Opening Day roster.

The 1952 Red Sox opened in Washington on April 15, with Throneberry batting fifth and playing right field. Despite an 0-for-4, two-strikeout performance at the plate, Faye made “two sparkling catches” and drove in the final run of the afternoon with a long fly ball as Boston’s Mel Parnell blanked the home team, 3-0, before a crowd of 25,869 that included President Harry S. Truman. “I hope I hit better the next chance I get,” commented the rookie after his big-league bow.13 After a 1-for-4 the next day, on April 17 he hit his first major league home run, a grand slam off Washington’s Don Johnson.

In the team’s home opener, Throneberry scored the winning run in the 10th inning of the 5-4 victory. One “H.W. Shortswallow” of the Boston Herald celebrated Faye in verse:

In the tenth, Mrs. Throneberry’s youngster named Faye

Drew a walk, went to second as Goodman made hay

With a single to left. This brought up ol’ Dutch

And again, Mr. Vollmer won the game

—In the clutch!14

Despite the great start, Throneberry was not ready to star in the major leagues, hitting just .216 in April; though he got his average to .306 on May 6 he tailed off to .259 on May 11. “The kid’s failure to connect threatens to get him down,” wrote the Herald’s Bill Cunningham.15 His fellow sportswriter at the Herald, Arthur Sampson, observed, “Throneberry is a youngster of outstanding ability who may be a solid, all-around outfielder some day, but who has a few weaknesses at this stage that he must overcome before he can be considered a definite regular.”16

One of those weaknesses was his work in the outfield, where Throneberry had problems with Fenway Park’s notorious “sun field” in right. “We played just about all night games last year at Scranton, except for Sunday. I’ve got a lot to learn about the wind, the sun, and sunglasses,” he admitted. The Red Sox manager, Lou Boudreau agreed. “Faye’s learning the sun field the hard way. We could work him in the morning, but the sun isn’t right then, of course, so he’ll have to learn it under fire.” 17 His miscue on Gil Coan’s third-inning single on April 21 resulted in a key run, and a 3 -2 loss to Washington at Fenway Park. The error diminished Throneberry’s throwing out the Senators’ Irv Noren at home twice that afternoon with strong throws to the plate.

Ted Williams’ departure for the Marines in April provided a fair amount of playing time in the outfield, but even after a second grand slam — off Cleveland’s Early Wynn at Fenway Park on May 4 — Throneberry continued to struggle. On June 10, hitting just .222, Faye was optioned to Triple-A Louisville. He returned just a few weeks later, and hit well enough to play semi-regularly the rest of the season. His final rookie numbers were .258 with five home runs and 23 runs batted in in 98 games.

In November Throneberry joined the US Army for what turned out to be a two-year hitch. He did his basic training at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, and spent some time in Korea during his stint.

When Throneberry returned for the 1955 season, the Red Sox had an opening in left field. Ted Williams had announced his retirement, though many believed it would be temporary. Throneberry hit well in the spring, and credited a new stance. “I used to bat open, but I closed it,” he said. The results were almost immediate. “I like Throneberry a lot,” announced rookie skipper Pinky Higgins on March 21. “As the situation stands at present, he’d be my left fielder on opening day if Williams was not around… The boy has improved all-around since I had him in the minors [13 games with Louisville in ‘52].18 Throneberry’s play has been the most pleasant surprise of the training season,” he told another reporter. 19

“That Throneberry has improved greatly and really covers the ground,” seconded general manager Joe Cronin. 20 By April, Higgins boldly predicted that “Throneberry will eventually be a great ball player.”21 Faye led all Red Sox batters in hits and RBIs in spring training, batting .285. The press took notice as well. An Associated Press writer rated Faye among the most improved hitters in spring training, a list that also included Hank Aaron and Moose Skowron.22 The Herald opined that while Throneberry “was no Williams…he swings hard and occasionally connects for 400-foot drives. He has far more speed than Williams and has a much stronger arm than Ted.”23

Throneberry was named Boston’s starting left fielder. “Fill the shoes of Ted Williams?” he saidd. “Not me. And that’s not said with any lack of confidence. But you just don’t fill the shoes of a ball player like him. If he came tomorrow, I’d expect to go to the bench.”24 April 1955 was the pinnacle of Faye Throneberry’s baseball career. For the month, he batted .362 with four home runs and 17 RBIs, posted a .424 on-base percentage, and played a solid left field. The Boston media was cautiously optimistic. After a great opening series, Herald cartoonist Vic Johnson dubbed him “fiery Faye Throneberry,”25 but the newspaper later warned, “He’s new. The pitchers don’t know him….But they’re studying him. They’ll be constantly working on him. They’ll feed him everything in their repertoire….They’ll be searching for his weakness, and if he hasn’t one, at least, the spot where he’s weaker. If they find it, word will whizz along the grapevine and he’ll get nothing else. It takes a couple of swings of the circuit to show whether a batter really has it.”26 On April 28, Throneberry’s batting average stood at .412. “I know that I made two of my hits off curveballs,” a self-satisfied Throneberry said with a grin.27

As the calendar turned from April to May, however, Faye began to slump. Facing the Indians pitching combination of Bob Feller and Herb Score in a May 1 doubleheader at Cleveland Municipal Stadium, Throneberry “didn’t come close to a base hit in seven trips to the plate.”28 Neither did too many other Red Sox hitters, but for Faye it started a slump. In the nightcap, he struck out four consecutive times against Score, a left-hander. He also had a terrible time with the sun, missing at least two or three drives hit to left field that should have been easily caught. Worst of all was the lazy, opposite-field fly poked by Larry Doby on an 0-and-2 pitch with two out and two on in the first inning of the nightcap. Faye “romped after this fly uncertainly, slipped to his knee and finally missed connection with the pop altogether as it dropped close to the wall and the left field foul line untouched for a fluke double,” and a pair of RBIs. 29 Boston lost, 2-1.

The worst for Throneberry came on May 7 at Fenway Park. Unsuccessfully diving for a Gil McDougald looping line drive in the fourth inning, Faye landed hard on his right shoulder and had to be removed from the game. At first the injury appeared to be slight, merely a bruise, but X-rays revealed “a slight shoulder separation” according to the team physician, Dr. Timothy Lamphier. 30 Leading Boston in batting average (.282) and RBIs (18) at the time, he remained out of the lineup until mid-June. By that time, Ted Williams had returned and reclaimed his left-field position. Throneberry became a spare outfielder. Playing sporadically the rest of the way, he ended what at first appeared to be a breakthrough season at .257 with six home runs and 27 RBIs in just 60 games for the fourth-place Red Sox.

The 1956 season was a complete washout for Throneberry. After two months in a reserve role, he underwent an emergency appendectomy on June 5. He remained out of action until August and did not start a game until September 30, the Red Sox’ final game of the season. He played just 24 games the entire season, hitting .220 with one home run.

Throneberry was planning to play the same role for the Red Sox in 1957, but after just one at bat (a strikeout) he was dealt (along with pitcher Russ Kemmerer and shortstop Milt Bolling) to Washington for pitchers Bob Chakales and Dean Stone. Washington manager Charlie Dressen hinted that he might use Throneberry in center field, but Dressen was fired one week after the deal. His successor, Cookie Lavagetto, played Throneberry primarily in center but also in both left field and right.

Throneberry finished the 1957 campaign at .184 with two home runs and 12 runs batted in. The next season, he repeated the .184 mark, this time appearing in a mere 44 games.

Perhaps Throneberry’s hitting struggles were due to his vision. He tried wearing glasses in 1959 and although the results were encouraging at first — he was hitting over .300 as late as July 11 as Washington’s regular right fielder — both Throneberry and the Senators slumped after that. Between July 19 and August 5, the club lost 17 straight games; their right fielder’s average dipping to .265. During the team’s slump, which plummeted Washington from fifth place into the cellar, Faye went 14-for-62 and lost his starting role to Lenny Green.

Writer Bob Addie noted another oddity of Faye’s 1959 season. Though he finished the season at .251, Throneberry was the team’s top hitter in night games (ranking 20th in the American League in that obscure category), a surprise, the columnist sarcastically noted, because he “had a tough enough time seeing in the daylight.”31

Throneberry enjoyed a good spring training for the Nats in 1960, batting .380. “I guess the ball is falling in for hits,”32 Faye evenly explained to Addie, who suggested that the outfielder had finally been given the proper eyeglasses. Or, at least, “has more confidence.”33 Manager Lavagetto believed Faye was about to finally realize the potential he had showed with Boston nearly a decade earlier. But Lenny Green again beat him for a starting outfielder’s berth, and Throneberry, whom Addie physically likened to “the candidate for sheriff in the Deep South…out of his baseball uniform,”34 would play most of the 1960 season as a utility man. Overall, he hit .248 with just one home run.

After the 1960 season, Throneberry was selected in the expansion draft by the brand new Los Angeles Angels. After extremely limited duty for the Angles (24 games, 31 at-bats, only five outfield appearances), Throneberry was optioned to Toronto of the International League on July 22. He bounced around the minors for a couple more seasons before he was finally released by the Pacific Coast League’s Tacoma Giants in 1963.

Ten years later, Faye was back in the news, in a fashion. He had become a professional bird dog trainer. Miller’s Miss Knight, a six-year-old white and orange pointer owned by Roger Hayes of Pulaski, Tennessee and trained by Throneberry was named Top US Field Trial Bird Dog of the year in 1973. Miss Knight (and Throneberry) won competitions in Grand Junction, Tennessee and Dallas, Texas. Faye was awarded $500, a plaque, and a bolo tie bearing the gold and silver Top Dog Award Emblem.35

Faye Throneberry died of heart failure at St. Francis Hospital in Memphis on April 26, 1999, and was buried two days later at Fisherville Cemetery. He was 67 years old. Faye was survived by two daughters (Sherry McPeake of Collierville and Karey Shearer of Arlington), a sister (Lurlene Peacock of Corsicana, Texas), a brother, Walter Throneberry of Collierville, and three grandchildren. Peggy Bobbitt Throneberry had passed away in 1994.36

Brother Marvin, whose major-league career lasted from 1955 through 1963, had also died in 1994.

Notes

1 Washington Post, April 7, 1960, D3.

2 Washington Post, May 13, 1960, C11.

3 Christian Science Monitor, April 19, 1955, 12.

4 On his death record in 1946, Walter Throneberry’s occupation is listed as Construction Foreman (the cause of death is not noted.) Thanks to Maurice Bouchard for genealogical research.

5 Baseball: Office of the Commissioner, Decision Nr. 36, 11 April 1950. Document contained in Throneberry’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

6 Ibid.

7 Hartford Courant, April 24, 1955, C3A.

8 The Sporting News, May 14, 1952.

9 The Sporting News, September 10, 1952, 2.

10 Hartford Courant, March 12, 1952, 15.

11 Ibid.

12 Boston Herald, April 14, 1952, 16.

13 Boston Herald, April 16, 1952, 23.

14 Boston Herald, April 19, 1952, 6.

15 Boston Herald, April 26, 1952, 6.

16 Boston Herald, April 28, 1952, 19.

17 Boston Herald, April 21, 1952, 15.

18 Christian Science Monitor, March 22, 1955, 16.

19 Hartford Courant, April 2, 1955, 12.

20 Boston Herald, April 5, 1955, 25.

21 Boston Herald, April 12, 1955, 22.

22 Boston Herald, April 3, 1955, 48.

23 Boston Herald, April 3, 1955: 50.

24 Christian Science Monitor, April 19, 1955, 12.

25 Boston Herald, April 18, 1955, 16.

26 Boston Herald, April 19, 1955, 33.

27 Ibid. Throneberry’s comment was made mid-streak.

28 Boston Herald, May 2, 1955, 14.

2929 Ibidem

30 Boston Herald, May 9, 1955, 13.

31 Washington Post, January 6, 1960, 25.

32 Washington Post, April 7, 1960, D3.

33 Washington Post, April 10, 1960, E5.

34 Washington Post, April 16, 1960, A8.

35 Noranda Monitor, Noranda, Quebec, September 6, 1973, 10. [Miller’s Miss Knight was inducted into the Hall of Fame, the Dogs Field Trial Hall of Fame, that is, in 1981. See http://www.birddogfoundation.com/Pointer_Setter_Hall_of_Fame.htm.]

36 Memphis Commercial Appeal, April 27, 1999, A6.

Full Name

Maynard Faye Throneberry

Born

June 22, 1931 at Fisherville, TN (USA)

Died

April 26, 1999 at Memphis, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.