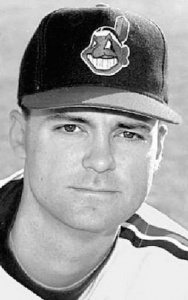

Steve Olin

When pitcher Steve Olin entered games at Cleveland Stadium, the organist would play the Beatles’ “Yellow Submarine” in recognition of the righty’s unusual low side-arm delivery.1 Indians general manager John Hart once described Olin as a 16th-round afterthought, a guy designated only to fill out a Class A roster. But Mike Hargrove, who managed Olin in the minors and with Cleveland, said, “When you got to know Steve, you were impressed with his courage and determination.”2

When pitcher Steve Olin entered games at Cleveland Stadium, the organist would play the Beatles’ “Yellow Submarine” in recognition of the righty’s unusual low side-arm delivery.1 Indians general manager John Hart once described Olin as a 16th-round afterthought, a guy designated only to fill out a Class A roster. But Mike Hargrove, who managed Olin in the minors and with Cleveland, said, “When you got to know Steve, you were impressed with his courage and determination.”2

Olin rose rapidly through the minors, and after pitching parts of three seasons in the big leagues from 1989 through 1991, he got 29 saves for the Indians in 1992. Like most submariners, he didn’t throw hard – but he had a heavy sinker, and so he was a pronounced ground-ball pitcher who seldom gave up homers.3

On March 22, 1993, however, Olin’s life was cut short in one of baseball’s better-known accidents. He and his teammate, fellow pitcher Tim Crews, both perished when Crews’ power boat crashed into a dock. Olin, who was just 27, “was one of baseball’s most promising young relief pitchers. . .the only thing stopping him from becoming a dominant closer was his inability to get left-handers out.”4

Steven Robert Olin was born on October 4, 1965 in Portland Oregon. He was one of three children (sisters Heather and Joell) born to Gary and Shirley (née Carstens) Olin. At a young age, young Olin developed his sidewinding pitching form while skipping rocks across lakes in his native state. Rick Wolff, the Indians’ roving psychological instructor, once said that Olin remembered how every coach – from Little League to high school – told him he could never make it to the majors as a submarine pitcher. “Oli just told them he wasn’t going to change his style,” Wolff said. “He said he made it on his own terms.”5

Olin was the pitching star at Beaverton High School, and kept sharp during the summer months pitching for Maletis in American Legion ball. His high school coach, Mike Bubalo, also managed the Maletis club.

After graduation from high school, Olin enrolled at Portland State University. He was thrown into the starting rotation as a freshman. In a doubleheader against Gonzaga, the young frosh hurler led the Vikings to a 9-2 win. He went the distance in a five-strikeout performance that raised his record to 6-1. “I think Steve’s doing well,” said PSU coach Jack Dunn. “All season we’ve thrown him to the lions. He goes out there and goes after them.”6 From then on, he was a mainstay for the team. During his four-year career, he was 29-24, with 31 complete games.7

As a senior, he shut out archrival University of Portland in the second game of a doubleheader, scattering five hits, striking out 10. “We played a good first game, and then the great equalizer took the mound,” University of Portland coach Terry Pollreisz said of Olin. “He didn’t throw a lot of good-hitting pitches. It was a whale of a game. Almost every pitch was a judgment pitch for the umpire. What he threw were great influence pitches. You either were influenced to swing or influenced not to swing.”8 Almost prophetically, Dunn said, “I’ve always said I think he’s a pro prospect as a reliever.”9

The Cleveland Indians selected Olin in the 16th round of the free agent draft on June 2, 1987. Olin reported to Burlington (North Carolina) of the Appalachian League. He was impressive in 25 games pitched, striking out 75 in 57 1/3 innings while walking just 17. His record was 4-4 with a 2.34 ERA. Olin was promoted to Class A in the 1988 season, splitting the season between Waterloo of the Midwest League and Kinston of the Carolina League. Between the two, Olin racked up 23 saves to go with a 2.34 ERA and 93 Ks in 96 innings. Apparently, Dunn knew what he was talking about with regards to Olin as a relief pitcher.

After the season, Olin married the former Patti McKelvey on November 5, 1988. The couple had three children, daughter Alexa, and twins, Garrett and Kaylee. Olin was deeply devoted to his family.

In 1989, Olin leapfrogged the AA level of the minor leagues, landing in Colorado Springs of the AAA Pacific Coast League. Rick Adair, the pitching coach in Colorado Springs, convinced Sky Sox skipper Mike Hargrove to make the unusual promotion.10 The young right-handed hurler again excelled, picking up 24 saves to go with a 4-1 record. “Olin does the job for us day in and day out,” said Hargrove. “If you’re looking for reasons, it’s because he has a unique delivery, an 84 to 86 mph fastball with good movement, an excellent slider and he throws strikes.”11 For his work at Colorado Springs, Olin was rewarded with the Rolaids Relief Award for the PCL in 1989.

After Greg Swindell went on the disabled list with an elbow problem, Olin was promoted to the Indians in late July, making his major league debut on July 29 against Boston. He threw 2 2/3 innings of scoreless relief. Cleveland manager Doc Edwards planned to use Olin in middle relief – but he added, “If Jonesy (Doug Jones) is not available, I’ll use the kid (Olin) as a closer.”12

Olin was sent back to Colorado Springs on August 1, but recalled a week later. He remained with the Indians for the remainder of the season. He picked up his first major league save on August 9, 1989 against New York at Yankee Stadium. He pitched 3 1/3 innings of scoreless relief of starter Rod Nichols. “I kind of had a feeling I would be back,” said Olin. “Doc (Edwards) and Mark (pitching coach Mark Wiley) told me they wanted me back. I wasn’t that disappointed going down.

“You have to go out and throw strikes. I didn’t want to let myself get caught up in all the hoopla of being in Yankee Stadium. It’s easy to see how things can get to you.”13 In September, John Hart replaced Edwards as the Indians manager. General Manager Hank Peters was retiring soon and Hart was being groomed to replace him. It was believed that by taking the reins of the club, Hart would get a better understanding of where things stood with regards to the talent. John McNamara was hired as the Indians manager in 1990.

If Olin had an Achilles heel, it was that he – like many pitchers with his type of delivery – had difficulty against left-handed batters. Although right handed-hitters only batted .209 against the rookie, left-handed batsmen hit .333. Olin made the Indians out of spring training in 1990. In early June, however, he was sent down to Colorado Springs for a month to develop a second pitch and to work on pitching to left-handed batters. “We want him to work on another pitch, a change-up or a slider, that will help him get left-handers out,” said McNamara.14

Early in Olin’s career, comparisons were made between him and Dan Quisenberry, the submarine-style relief ace of the Kansas City Royals. Quisenberry was winding down his career in 1990 with San Francisco. In spring training, Quisenberry was asked about the Tribe’s young side-arm pitcher. “I’ve seen a lot of young submariners in the last 10 years,” said Quiz. “Most of them have a tough time making it over the hump. But Olin has a very fluid motion. He has command of his breaking ball and already has a change-up. That puts him ahead of the game. Submariners have a tough time throwing a breaking ball. A lot of them don’t know exactly what they’re supposed to do. But Olin’s breaking ball is better than the one I’ve pitched my career with.”15

The Indians dealt Buddy Black to Toronto on September 16, 1990. They were short a starter, and chose Olin to take the hill the next evening against Milwaukee. They informed him of the assignment approximately 15 minutes before game time. “When they told me, my heart jumped in my throat,” said Olin. “I haven’t made a start since 1987 when I started at Portland State University. After the first couple of innings, I finally settled down. The score was tied 2-2, and I just told myself to think of it as another relief appearance. I just wanted to hold the tie.”16 He did more than hold the tie, as Olin – in his only start as a pro – went seven innings before giving way to Doug Jones. The Indians offense did just enough to back Olin in the 4-2 victory.

Cleveland finished in fourth place in the American League East Division in 1990 with a 77-85 record. They had rising stars including Albert Belle, Sandy Alomar Jr., Carlos Baerga and Olin to go with Greg Swindell, Tom Candiotti, Doug Jones and Brook Jacoby. Optimism was high, but the Indians fell to last place and lost 105 games in 1991. Mike Hargrove replaced McNamara on July 5.

Jones was having a particularly rough season. He had been a dependable closer for the Indians over the previous three years, but he was 1-7 with an ERA of 7.47 and six saves when he accepted a demotion to AAA Colorado Springs. From mid-May through mid-July, Olin also punched the clock at the Indians’ AAA affiliate to work on his mechanics and self-confidence. When he returned, Olin posted 17 saves from July 19 to the end of the season. However, he was still having trouble retiring left-handed batters – they hit .330 off him.

In the offseason, the Indians designated Jones for assignment. He eventually signed a free agent deal with Houston. His departure cleared the way for Olin to be the Indians’ closer for the 1992 season. “We want to build the bullpen around Steve Olin,” said Rick Adair, by then the pitching coach in Cleveland. “But he’s got to work his slider in to left-handers, not his fastball. And he’s got to get people out early in the count. We don’t want him pitching to people deep in the count.”17 Hargrove was a bit more succinct. “Steve has to throw strikes consistently. He has to believe in himself. And he’s got to pitch to left-handers effectively before he can be stamped a closer.”18

The Indians improved in 1992, tying for fourth place in their division with New York with a 76-86 record. Newcomer Kenny Lofton led the league in stolen bases with 66, though only Belle and Baerga hit over 20 home runs and 100 RBI. Charles Nagy was the only starter to post more than 10 wins on the pitching staff (17). Olin saved 29 games out of 36 opportunities. He ranked eighth in the American League in saves. He set a club record with appearances by a right-handed pitcher with 72. He posted an ERA of 2.34. But he still faced a steady diet of left-handed batters, who hit .324 off him. His final win came on September 9, 1992 at Milwaukee. Robin Yount’s single to right field off Jose Mesa was the 3,000th hit of his magnificent career. Olin entered the game in the eighth inning and pitched 1 2/3 scoreless innings. Cleveland was trailing 4-3 headed into the final frame. But they scored two unearned runs to win the game, 5-4. Olin raised his record to 8-4 with the victory.

Since 1947, the Cleveland Indians had called Tucson, Arizona home during spring training. In 1993, the club moved its headquarters to Winter Haven, Florida. In an effort to bolster their staff, the Indians signed starting pitchers Mike Bielecki and Bob Ojeda and reliever Tim Crews to free agent contracts.

The Indians had an off day on March 22, 1993 – their only one scheduled during that exhibition season. Many players took advantage of Winter Haven’s proximity to Orlando, and spent the day at Disney World. Crews, being the new addition to the team, invited the team to his home for a cookout. Crews lived on a 45-acre ranch off Little Lake Nellie in central Florida. Crews invited the whole team, but only Ojeda, Olin and strength coach Fernando Montes accepted.

The Olin family got lost trying to find the ranch. Patti Olin pleaded to just turn around and go home, but Steve was adamant that they would find it. The day stretched into evening. “So right after dinner we all kind of cleaned up, walked outside, and we all rode down and hitched the trailer up to get ready to launch the boat,” said Montes. “We forgot something up at the house and Perry Brigmond, who was a friend of Tim Crews, had just arrived prior to us going down. And the question was, OK, who is going to go up and get it? Nobody kind of volunteered, so we played this child’s game. We called rock, paper, scissors, and I don’t recall what my actual one ended up as but, in all I ended up losing.”19

Crews, Ojeda and Olin climbed into the 18-foot bass boat, and circled around the lake. A neighbor’s dock, which extended more than 50 yards, sat on the far side of the lake. As Crews accelerated, the front of the boat rose up, blocking their vision. As soon as the boat planed out, it was now under the dock. It was too late. The accident occurred in three feet of water. “We heard this loud thump and a crash,” said Montes. “And it was silence, utter silence. I knew without any hesitation that Steve Olin had passed.”20

“They almost turned around and came back to Winter Haven,” said Bob DiBiasio, Indians Vice President of Public Relations. “It’s a terrible thing to happen, especially when you consider how Steve almost didn’t go to the cookout because he got lost trying to find the Crews’ farm. But he promised Alexa a horseback ride as one of her birthday presents and he was going to see that she got it.”21 Alexa Olin had turned three years old the day before.

“Steve was more to us than just a pitcher,” said Hargrove. “When things start flying around, you want people who don’t look for holes. You want people who will stand up and take it with you. Steve Olin was that kind of guy. So was Tim Crews.”22

Steve Olin passed away instantly. Tim Crews was airlifted to the Orlando Medical Center, and was pronounced dead the next day. They both died from massive head injuries. Bob Ojeda, who was slouching in his seat, was hurt the least, suffering lacerations on his head. He made a complete recovery and pitched for Cleveland in August 1993.

The investigators at the site found three four-inch posts sheared off. Four factors contributed to the accident: darkness, the boat speed, an unlit dock and alcohol. It was determined that Crews blood-alcohol content was .14, over the legal limit in Florida.

The Indians held a memorial service near their spring training site to honor Olin and Crews. A few days later, Hargrove, Adair and members of the Indians bullpen made the trip to Portland for Olin’s funeral. One of Olin’s favorite songs, “The Dance” by Garth Brooks, was played at the conclusion of the service. Cleveland did not have another off day in spring training for the next seven years.

April 5, 1993 was bound to be an emotional day for Cleveland Indians fans. It was the final Opening Day at Cleveland Stadium. After many decades of calling the mammoth stadium home, the Tribe was moving across downtown to the Gateway District. There, a new open-air stadium would be awaiting them for the 1994 season. Many memories for fans were of the sentimental variety: their first ballgame, a first date, a family outing. But that is what makes memories special; they are exclusive to the individuals who hold them. Unfortunately, not many folks were reminiscing about past winning seasons. Two World Series appearances, the last in 1954, left the remnants of winning baseball to history books and microfilm.

Still, there was a twist to the plot on that cold April day. A capacity crowd of 73,290 braved the 36-degree weather to settle in for the pregame activities. Bob Feller threw out the ceremonial first pitch. The Indians and their guests, the New York Yankees, were introduced to the crowd as they took their place on the respective baselines.

But another part of the Opening Day ceremony left many somber and melancholy. The widows, Patti Olin and Laura Crews, and their families were presented with their husbands’ jerseys. John Hart, Mike Hargrove, as well as Indians relief pitchers, Kevin Wickander, Derek Lilliquist, Eric Plunk and Ted Power took part in the ceremony at home plate. After a moment of silence, the four relievers gave a “thumbs up” to the heavens before heading out to the bullpen.

“I didn’t know it would be that emotional,” said Wickander, who broke down in Patti’s arms.23 Wickander and Olin were good friends; Olin served as best man at Wick’s wedding. But his locker, right next to Wickander’s in the clubhouse, would remain empty for the entire season. “He had the heart of a lion, the guts of a burglar,” said Hart. “He courageously threw that fringe stuff up there and got people out.”24

Perhaps there was too much emotion for the Indians. Jimmy Key cruised to a 9-1 win, holding the Tribe to three hits over eight innings of work. “Opening Day is something you want to get out of the way, but you want to do it in a positive way,” said Sandy Alomar. “We had to honor Crews and Olin. Their families deserved it. I just wish we could have won.”25

The Indians signed Dave Winfield to a contract on April 5, 1995. Winfield wore the number 31 for the majority of his career. But the same number had also been worn by Steve Olin. Before the Indians issued the number to Winfield, they called Patti Olin as a courtesy. “She said it was OK,” said Winfield. “So every day I wear it, I’ll think of Steve. “Hopefully, in a way, he’ll still be making a contribution to the team.”26

On September 8, 1995, the Indians beat the Baltimore Orioles, 3-2. The victory sent Cleveland to the postseason for the first time in 41 years. During the celebration, Hargrove requested that the song “The Dance” be played over the public address system. “I thought it would mean a lot to anyone who was there (with the Indians at the time of the accident in 1993),” said Hargrove. “For those who weren’t there, it had no significance, but it was still a good song. It was a tribute to those guys, to their families. It was part of our promise to never forget them. We didn’t tell anyone that we were going to do it. For those who knew, there wasn’t a dry eye to be seen. I saw Charlie Nagy, tears rolling down his face.”27

Notes

1 “Music Cue”, Associated Press, December 31, 1992.

2 Sam Donnellon, “Tribe Family in Mourning”, Philadelphia Daily News, March 25, 1993.

3 For his major-league career, his groundball/flyball ratio was 1.43, vs. the MLB average of 0.80. He allowed just 14 homers in 273 innings.

4 “Indians’ luck all bad in Florida”, Associated Press, March 24, 1993.

5 “Cleveland Indians”, Chicago Tribune, March 24, 1993.

6 Jim Beseda, “Vikings sweep Zags, up lead”, The Oregonian, May 5, 1984: E5

7 “Olin never forgot roots in Portland”, Associated Press, March 25, 1993.

8 Nick Bertram, “PSU comes back to split twin bill with Pilots; Cougars Lose Twice”, The Oregonian, May 3, 1987: F10

9 Ibid.

10 Donnellon, “Tribe Family in Mourning”

11 Russell Schneider, “Medina batting just .148”, Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 23, 1989: 9-D

12 Russell Schneider, “Snyder’s Ailment is back”, Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 29, 1989: 3-D

13 Joe Maxse, “Rookie submariner tough on Yankees”, Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 11, 1989: 7-D

14 Russell Schneider, “Reliever Kaiser is called up”, Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 11, 1990: 3-D

15 Paul Hoynes, “Tribe’s Olin passes Quiz’s inspection”, Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 8, 1990: 2-D

16 Paul Hoynes, “Olin bails out Indians,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 18, 1990: 2-D

17 Paul Hoynes, “Finding closer is high priority for Hargrove”, Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 24, 1992: 1F

18 Hoynes, “Finding closer is high priority for Hargrove”

19 ESPN, Outside the Lines, Indians Boating Tragedy, March 18, 2003

20 Ibid

21 James F. McCarty and Paul Hoynes, “The Tribe’s tragedy; ‘They never knew what hit them’”, Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 25, 1993: 1A

22 Paul Hoynes, “Accident stuns teammates; tears hint depth of mourning”, Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 24, 1993: 1E

23 Paul Hoynes, “A poignant time; Thoughts of best friend Olin stir Wickander”, Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 6, 1993: 7E

24 Bud Shaw, “A moonless evening, a quiet lake, a tragedy; Recounting the 1993 deaths of Indians pitchers Steve Olin and Tim Crews”, Cleveland.com, March 22, 2011

25 Paul Hoynes, “Key spoils Indians opener; 73,290 see Yankees win, 9-1”, Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 6, 1993: 1E

26 USA Today, “Winfield to wear Olin’s No. 31”, April 7, 1995, Players File, Baseball Hall of Fame

27 Tim Kurkjian, “In times of despair, Hargrove stands tall”, ESPN.com, March 21, 2003

Full Name

Steven Robert Olin

Born

October 4, 1965 at Portland, OR (USA)

Died

March 22, 1993 at Little Lake Nellie, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.