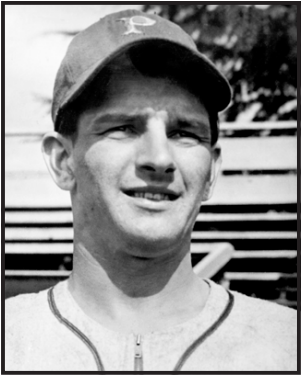

Frankie Zak

When you gaze at the career of wartime Pittsburgh Pirates shortstop Frankie Zak, you see the statistics of an unimpressive backup who played during an era when the game was filled with minor leaguers and 4-F players, those who were physically unable to serve in the military. He had only 240 plate appearances in his short major-league career, hitting .269 with no home runs. He normally would have been a long-forgotten part of the game, primarily known only to members of his family. There is one thing that makes Zak a memorable oddity in the history of the sport: He was an All-Star. The shortstop is almost unanimously considered to be the strangest choice in the long history of the midsummer classic.

Born in Passaic, New Jersey, on February 22, 1922, Zak was a smallish all-around athlete, 5-feet-10 and never weighing more than 150 pounds. His parents, Thomas and Victoria Zak, were Polish immigrants. At the time of the 1930 census, Thomas was listed as a dyer in a dye shop and Victoria worked as an operator in a handkerchief factory. Ten years later, Frankie still lived in the family home in Passaic with his widowed mother, his two older brothers, Fred and Stanley, and their wives, Barbara and Beatrice. Victoria Zak was then working as a laborer in a wire cable factory.

A quick player with little power, Zak did not embrace baseball as his favorite sport, and his professional career was nothing more than a fluke, thanks to a high-school teammate, future major-league umpire Ed Sudol.

Sudol, who was part of the umpiring crew for Jim Bunning’s perfect game in 1964 and Hank Aaron’s memorable 715th home run, in 1974, was in his second season in professional baseball in 1941, playing for the Tarboro Orioles in the Class D Coastal Plain League, when his old teammate Zak paid him a visit. The Passaic native’s timing was impeccable; he learned the Orioles were without a shortstop when he arrived in Tarboro, so the team offered him a contract to play a position he had never played before.

Zak’s first season was adequate. He hit .255, although his power was almost nonexistent; only six of his 55 hits went for extra bases. Regardless of the issues he had in his rookie minor-league campaign, Zak would get an opportunity to advance his new career, partly because the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor and the country was plunged into the Second World War

Many of the game’s best players, both in the major and minor leagues, were either drafted or enlisting in the armed forces, creating a dearth of players. Looking for whatever talent they could find, the Pittsburgh Pirates signed Zak and assigned him to their Hornell (New York) club in the Class D PONY (Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York) League. It was there that the 20-year-old demonstrated that he had potential, raising his average to .271 while showing increased power with 17 doubles and the only two home runs he would hit in his professional career.

In 1943 Zak went to spring training camp with Pittsburgh at Muncie, Indiana, where the Pirates were forced to train due to wartime travel restrictions. Though he didn’t make the team, he was promoted to the Pirates’ top minor-league squad, the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League. The New Jersey native regressed from an offensive standpoint, dropping 25 points to .246 while his slugging went from .328 in 1942 to .267. What he did have in his favor was the fact that he was a patient hitter with a solid .375 on-base percentage, and by 1943 he was developing into an effective fielder, posting a .936 fielding percentage, a full 31 points higher than his previous best.

After helping the Maple Leafs to the pennant in 1943, Zak reached the majors the following season. Even though it’s true that he may have never approached major-league baseball if not for the war, it gave the 22-year-old the opportunity to become a memorable if dubious part of its history.

Three games into the season, Zak made his major-league debut, as a pinch-runner for catcher Al Lopez against the Cincinnati Reds. With the Bucs down by three runs, Lopez had reached on a two-out bunt single, plating Vince DiMaggio to make it 4-2. Manager Frankie Frisch inserted the speedy Zak to run for Lopez. Johnny Barrett then slashed what looked like a hit up the middle but Cincinnati second baseman Woody Williams made a tremendous stop and tossed it to shortstop Eddie Miller for a game-ending force out of Zak.

The pattern continued for the young shortstop over the next month and a half; he played in 11 more games, each time as a pinch-runner or a defensive replacement, and scored five runs without a plate appearance. Finally, as June began, he started against the Brooklyn Dodgers and made the most of the opportunity. Starting shortstop Frank Gustine was in a slump so Frisch decided to give him a break. Zak singled in his first major-league at-bat. Dodgers pitcher Curt Davis had Zak picked off at first, but overthrew first baseman Howie Schultz and Zak went to second on the play. Gustine eventually replaced Zak in the contest but not before he ended a perfect 2-for-2 first start with a fifth-inning single.

Impressed with what he saw, Frisch continued to use his young shortstop over the next nine days. Zak became a spark plug, reeling off 14 hits in 11 games, including a four-hit performance on June 10 that lifted his batting average to sparkling .538. While the nation’s thoughts were with the GIs who had landed on the beaches of Normandy four days earlier, baseball was providing a diversion to a worried country and Zak helped ease the tensions of Pittsburgh on the 10th with four singles, two runs, and an RBI, helping the Pirates to a 9-4 victory over the Chicago Cubs.

Zak eventually cooled down, going 14 at-bats without a hit before an RBI single on June 22. But he continued to be an effective option off the bench for Frisch, hitting .305 with a .387 on-base percentage in 44 appearances going into the All-Star break. Nonetheless, odds were infinitesimal that a utility player like Zak would have any chance at playing in the All-Star Game, which was scheduled for Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field on July 11.

Eddie Miller, who made the game-ending putout on Zak in his first major-league game, had been selected as the backup to starting shortstop Marty Marion for the National League. But Miller was injured and while there were many better options to replace him, including Frank Gustine or even versatile teammate Pete Coscarart, Zak was spending the All-Star break in Pittsburgh while Gustine and Coscarart were not. Since there were travel restrictions in place because of the war, Zak was once again in the right place at the right time and was chosen to represent his league in the midsummer classic.

Despite the fact that Zak had few at-bats and was not exactly the proper choice for such an honor, Pirates fans and players were thrilled that he was selected. Zak had brought an enthusiastic attitude to the franchise in his rookie season. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette writer Al Abrams said of him, “If you happen to sit on the third base side when the Bucs are at home, you can’t help but hearing Frankie chattering away or giving out with those long whistles during every second of action.” Abrams added, “Veterans on this club are amused by the way he rushes to a pitcher in trouble and gives him encouragement. It’s the type of spirit found mostly in high schools and colleges.”1 Zak’s manager at Toronto, future Hall of Famer Burleigh Grimes, likened him to Pee Wee Reese when Reese was a young player.

While Zak never made it into the contest, his inclusion in the All-Star Game made him a footnote in the game’s history. In a 2009 article in Time, Zak was at the top of the list of the 10 worst All-Stars. Sportsonearth.com put him at shortstop on its worst-ever all-star team, noting that after the All-Star Game, “Zak returned to his role as a bench player among wartime replacements, ending his career with 208 official at bats, a .269 average, zero homers, and the distinction of being the weakest player ever to appear on an All-Star roster. He served his country well, though, by preventing a trip that wasn’t really necessary.”2

Unfortunately for Zak, Grimes was wrong; Zak wasn’t anywhere close to Pee Wee Reese in talent, just a spark plug for a brief time during the war. He finished the season with 160 at-bats and a.300 batting average, but batted only 48 more times for the Pirates over the next two seasons while splitting time between Pittsburgh and Kansas City of the American Association.

Even though his major-league career was close to being over, Zak was the subject of two interesting stories in 1945 and 1946. In the fifth inning of the season opener in 1945 at Cincinnati, he called time out at second base to tie his shoelaces. Second-base umpire Ziggy Sears was trying frantically to get the attention of the home-plate umpire and pitcher to tell them time was out. No one noticed, the pitch was thrown, and Jim Russell hit a three-run homer. The home run was disallowed because of the time out and the Pirates ended up losing the game. 7-6.

One day in 1946, at a game in Chicago, Zak was trying to impress the mother of a girl he was dating. According to Al Lopez, who told the story when he was manager of the Indians, “I even knew a fellow whose romance was broken up by a foul ball in the stands. His name was Frankie Zak — a shortstop when I was catching for Pittsburgh — and he fell in love with a Chicago girl. There was only one hitch. The girl’s mother didn’t want her daughter to have anything to do with a professional ballplayer. Frankie thought he knew how to break down a mother’s prejudice. He arranged for the girl to bring her mother to a game. We were in Wrigley Field and it was Ladies’ Day — 20,000 women in the park. And of all those people, who do you suppose got the foul ball in the face? That’s right, the girl’s mother. She was really hurt, too. And that was the end of the romance.”3

After his three seasons with the Pirates, Zak was selected by the St Louis Browns in the Rule 5 draft, then was being sent to the Yankees organization. He played in 1947 for the Newark Bears, in 1948 for the Portland Beavers, and was out of professional baseball after a 1949 season in which he played in 84 games for Oklahoma City, 40 for Portland, and 12 for San Diego.

While Zak’s major-league career was very abbreviated, he and his wife, Helen, remained loyal fans of the franchise; in fact the 77-year old Helen was in attendance for the last Pirates game at Three Rivers Stadium in 2000. Frank had died of a heart attack at the age of 49 in 1972, 16 days before his 50th birthday. After baseball, Zak had worked at United Wool Company in Passaic.4

Even though it may not be greatest way to be remembered, Zak continues to be celebrated as one of the worst All-Star players ever, a spot that he promises to hold down long into the future.

Notes

1 Al Abrams, “Sidelights on Sports,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 13, 1944, 13.

2 Mike Tanier, “Island of Misfit All Stars,” SportsonEarth.com, July 10, 2013.

3 Gary Joseph Cieradkowski, “40. Frankie Zak, My Favorite Player,” Infinite Cardset Blogspot.com, July 30, 2010.

4 Bill Lee, The Baseball Necrology (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 441.

Full Name

Frank Thomas Zak

Born

February 22, 1922 at Passaic, NJ (USA)

Died

February 6, 1972 at Passaic, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.