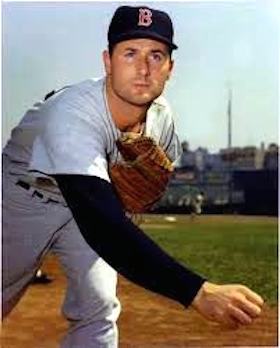

Bill Monbouquette

Bill Monbouquette grew up just a few miles from Fenway Park and was signed by his hometown Boston Red Sox, but his first day with the team, the cops threw both him and his father into a holding cell at the ballpark.

Bill Monbouquette grew up just a few miles from Fenway Park and was signed by his hometown Boston Red Sox, but his first day with the team, the cops threw both him and his father into a holding cell at the ballpark.

“I remember sitting out in the right-field stands at Fenway watching a game with my mom and dad right after I signed. These two guys behind us were swearing and drinking, and they spilled some of the booze on my mother. I looked at my father, he just nodded, and we proceeded to take care of these two guys. The next thing you know two cops came along and they take my father and I into some kind of holding cell in the bowels of the ballpark. This big cop is trying to pronounce my name, and he keeps getting it wrong. I asked him to please call upstairs to Johnny Murphy, the Sox farm director, and when he still can’t pronounce my name I ask if I can talk to him. I get on and say, ‘Mr. Murphy, I’m down here in this holding cell with my dad,’ and then I tell him what happened. He says, ‘I’ll be right down,’ and we get out. That was my first day with the Red Sox!”1

He grew up in a tough neighborhood in West Medford, Massachusetts, and he had a bulldog demeanor as a ballplayer. Both parents were Boston natives. Father Frederick Monbouquette worked as an electrician at night for the H.P. Hood milk company. He and his wife Catherine (Field) had five children: William Charles and Danielle, then Fred Jr., Jackie, and Cathy. The family name was French, and newspapers sometimes dubbed him a “fiery Frenchman,” but three of Bill’s four grandparents were Irish. Only his paternal grandfather was of French origin.2 Bill was fiery, though, and combative, bringing an urban toughness to his game.

Bill was born on August 11, 1936, and he went to Medford High School. He was throwing from an early age. When he was called up to the Red Sox, Catherine Monbouquette said he’d broken his first window—a third-floor window—when he was three years old!3

He was a Boston Braves fan in his youth, though. “You think about how great Jackie Robinson was. I saw him when I was a kid growing up. I saw Jackie play over at Braves Field. We used to go there as Knotholers. That’s where I went. I never came here [Fenway Park].”4

He played cadet and midget ball, American Legion ball, and then high school baseball. He also played semipro ball for the Red Birds of neighboring Everett, Massachusetts. Pitching in high school for the Medford Mustangs, he first made the Boston newspapers in the spring of 1953, when the paper noted him throwing a two-hitter with 12 strikeouts in a game against Quincy.5 With a surname as long as his, the newspapers sometimes abbreviated it in box scores as “M’b’q’te.” He often hit third in the order. Coach Art Terrill called him “our best pitcher; our best outfielder when not pitching; our best hitter….”6 Monbouquette also played on the high school hockey and soccer teams, but eschewed football. He also played for the St. Raphael amateur team.

In August 1954, he represented New England as starting pitcher in the annual Hearst Sandlot Classic at the Polo Grounds in New York on his 18th birthday. He pitched the first two innings and struck out five of the six batters he faced. He was the unanimous choice as the MVP. In his senior year, he pitched in 17 of Medford’s 23 games, was 10-4, and played center field when he wasn’t pitching, batting .375. His high school record was 20-8, and on June 20, 1955, he signed with the Red Sox, the signing credited to Sox scout Freddie Maguire.

He was 5-feet-11, weighed 190 pounds, and a right-hander—though, oddly, he wrote and performed all other functions left-handed. Monbouquette, whose nickname was originally “Farmer,” was assigned to the Appalachian League (Class D) to pitch for the Bluefield, West Virginia Blue-Grays, the Red Sox farm team there. He was 2-4, but had a 3.06 earned run average and made a good showing. There were two games he pitched that both ended in 2-2 ties, one that went 10 innings against Johnson City, and another that went 12 innings against Pulaski.7

His first full season was for Corning, also in Class D, with a 15-7 record and a 2.45 ERA.

The Greensboro Patriots (Class B) were his team in 1957; he was 11-6 (3.77). He also had the opportunity to pitch 32 innings in six games for Class-A Albany. He was 1-1 with a 5.57 ERA. In 1958, his last year in the minor leagues, he pitched in Triple A for the Minneapolis Millers. He was 8-9, but finished with a strong 3.16 ERA. He was brought up to Boston in mid-July. “We need starters,” said Red Sox manager Mike Higgins.

Monbouquette was only 21 years old when he got his first start on July 18. He pitched five innings against the visiting Detroit Tigers. He gave up five runs, three earned, and left with the game tied, 5-5. Billy Martin had stolen home on him in the very first inning; teammate Frank Malzone won the 11-9 game in the seventh with a grand slam. Red Sox pitching coach Boo Ferriss was pleased that, even with the pressure of pitching in his hometown, he only walked one batter in his debut—the first man he faced.

His first two decisions were losses, but they were close games—a 3-1 loss on July 23 at Kansas City (only one run was earned) and a 3-2 loss in Detroit on July 31. On August 5 at Fenway, he got his first win, a complete-game 7-1 decision over Washington. The Christian Science Monitor noted in a headline that the Red Sox “Finally Give Bill Monbouquette Big League Support.”8 By the end of the season, he had pitched in ten games and was 3-4 with a 3.31 ERA, second-best on the team.

Near the end of the season, he entered the United States Army and served in the 182nd Medical Unit at Camp Curtis in Massachusetts from September 21 into July 1959, though he was able to appear in games throughout.

Monbouquette was 7-7 that year with a 4.15 ERA. It was the year that the Red Sox finally became the last team in the majors to desegregate, when they brought Pumpsie Green and Earl Wilson to Boston. “Monbo” had a run-in with coach Del Baker, who was ragging on a player from the opposing team. “He used the N word, and Mike Higgins used the N word, and I told them, ‘I don’t want to hear that’ and then he [Baker] started to give me a bunch of crap, and I said, ‘I’m going to tell you something. I’ll knock you right on your ass. I don’t care if you’re the coach or not.’ I said, ‘You don’t do things like that!’ I grew up in a black neighborhood, West Medford. They were in our house. We were in their houses. There was none of that. To me, there was no sense to that whatsoever.”9 This was no established pitcher speaking up, but a 22-year-old standing up to a veteran coach in the days before multi-year contracts and without a strong Players Association to defend him.

The Red Sox finished in seventh place in 1960, 32 games behind the first-place Yankees. Monbouquette led the team with 14 wins, four more than anyone else. His standout game was a 4-0 one-hitter on May 7. He also pitched in the All-Star Game that year, starting the first of the two games that year. He’d shut out the league-leading Yankees in his last start, but he was shelled in the All-Star Game, giving up four runs in the first two innings and bearing the loss. He was also named to the squad in 1962 and 1963, but pitched in neither.

He won 14 games again in 1961, just one behind Don Schwall, this time his best game a 17-strikeout win over Washington on May 21. It set a Red Sox team record at the time, topping the 15 struck out by Smoky Joe Wood back in 1911, and set a night-game record in the American League.10 President Dwight Eisenhower, who’d attended the game, beckoned him over to shake hands. He came within one K of matching the major-league record at the time, and indeed would have had 18 if Jim Pagliaroni had not dropped a fouled third strike in the eighth. “I had the ball in the webbing of my glove, and it popped out. I felt like digging a hole under home plate and crawling into it.”11 Monbo credited pitching coach Sal Maglie for urging him to warm up an extra four minutes or so before the game and to end the session throwing a lot of breaking balls. He finished 14-14, but six of his losses were one-run games, four of them before the end of May.

The Sox finished dead last in 1962, but Monbouquette won 15 and threw a no-hitter against the White Sox on August 1. A tight 1-0 game, Boston scored its one run in the eighth inning off Early Wynn. He admitted to having been nervous. “I can remember standing on the rubber in the eighth inning—I was really shaking.”12 At the time, he said, “That was the biggest thrill I ever had. That was something very special because I hadn’t won a game in close to two months. I was struggling.”13 He’d lost three of four starts in July. “I had Aparicio 0 and 2 and threw him a slider off the plate. He tried to hold up, and I thought he went all the way. The umpire, Bill McKinley, called it a ball, and as I was getting the ball back from the catcher, someone shouted from the stands, ‘They shot the wrong McKinley.’ I had to back off the mound because I had a little chuckle to myself.

“The next pitch, I threw him another slider and he swung and missed.” When the team arrived home, “the city sent fire engines, lights flashing, to meet the plane at Logan Airport and give him a parade ride home.”14

Monbo’s best year in some regards was 1963, playing under first-year manager Johnny Pesky. The Sox finished in seventh place (76-85), and yet his record was 20-10, fourth in the league in wins, with a 3.81 ERA. The Yankees finished first for the fourth year in a row. He was a “Yankee killer” that year, beating them four times in five starts. On the downside, he led the league in base hits allowed (258) and earned runs allowed (113).

In October, he married a United Airlines stewardess from Edmonton, Alberta named Patricia Overton.15 He’d met her on the team charter the very night he’d thrown his no-hitter; a hockey fan herself, she didn’t really know baseball..

The ’64 Sox finished eighth. Reliever Dick Radatz won a surprising 16 games, but Monbouquette was first among the relievers (despite a losing 13-14 record), with a 4.04 ERA. He again allowed precisely 258 base hits, again leading the league. The old Red Sox record for gopher balls was 31, set by Gene Conley in 1961. Monbo would have set the new record, giving up 34 homers, except that Earl Wilson gave up 37. One of the homers cost him a tough 2-1 loss to the Twins on September 6. It was a complete game one-hitter, but the one hit was a homer in the bottom of the sixth by Zoilo Versalles after Rich Rollins had reached on an error.

In 1965, his 18 losses were the most in the league (10-18, despite an improved 3.70). The Sox slipped another notch down the ladder, to ninth place. In October, the Red Sox traded Monbouquette to the Detroit Tigers, getting three players in return: George Smith, George Thomas, and (more than a year later) Jackie Moore. Red Sox manager Billy Herman talked of Monbo being a real workhouse for the team and explained, “You’ve got to give to get. We need to plug holes in our club and we’re going to go with younger players, especially pitchers.”16 The Boston Herald published a photo of Bill and Patricia Monbouquette looking very happy. He said, “I sort of knew…when you have two bad years, you expect it. It’s a big break for me, and I’m happy…I still think I’m a good pitcher.”17 He told the Globe, “I’ve been awfully tired of playing on a losing team.”18

Bill Monbouquette pitched in 1966 for the Tigers and two games in 1967. He was 7-8, all in 1966, working 16 games in relief and starting just 14. The Red Sox went nowhere in 1966, with no pitcher winning more than Jose Santiago’s 12 wins. The Tigers advanced from fourth place to third. Denny McLain won 20, Mickey Lolich won 14, and Earl Wilson won 13. Monbouquette was a disappointment, with an ERA of 4.73, more than a full run worse than the year before. He’d struggled with control, unable to master his curveball, and after June 14 found himself mainly working out of the bullpen. He did win his 100th major-league game during the season. Understandably, there had been a lot of negative reaction from fandom and pundits in New England, but by the end of the 1966 season, many felt the Sox had made a good trade. Monbo himself said, “It was a wasted year, the most disgusting I’ve had in baseball.”19

The Tigers brought in a new manager (Mayo Smith) in 1967 and a new pitching coach (Johnny Sain). Monbouquette said, “Don’t give up on me…I know I must prove myself all over again, but I felt they gave up on me last summer.” He added, “I’m not a relief pitcher…I can’t relieve. It takes me too long to get warmed up.”20

In fact, his days as a regular starter were over. Before the 1967 season began, the Tigers said he would work out of the bullpen. And there was almost none of that—he threw one inning on April 16 and one on the 22nd. He didn’t give up any runs in either outing, but the Tigers asked him to report to the minors, to Toledo, and he refused, so they placed him on waivers and then gave him his unconditional release on May 10. Tiger starters were pitching so well they thought they could go with 11 pitchers. He told the Globe, “I thought I might be traded, but I never thought I’d be released.”21

He reached out to almost every big-league team, but no one was interested at first. He wasn’t ready to retire to the rug and drapery business he had in Massachusetts. After all, he was only 31 years old. Finally, the New York Yankees gave him a chance to make the team and he pitched for them in a May 26 exhibition game against Syracuse. He signed as a free agent with them on the 31st, replacing Jim Bouton on the staff. He had recovered his control, and threw 133 1/3 innings (10 starts, the first one on August 19, and 23 relief appearances) with a very good 2.36 ERA for Ralph Houk’s ninth-place Yankees.

There were two games of very long relief, both following Yankees starter Fred Talbot. The first was on July 26 in the second game of a doubleheader against the visiting Minnesota Twins. Talbot worked seven innings, allowing just two runs (one earned) but, with the score tied 2-2, he was taken out for a pinch-hitter in the bottom of the seventh. Monbo pitched nine full innings of shutout ball—the eighth through the 16th—before turning the ball over to Joe Verbanic. In the top of the 18th, the Twins scored once off Thad Tillotson and won the game. On August 8 in Anaheim, Talbot was hit by a line drive and had to leave the game. Monbo pitched innings three through nine, all scoreless, preserving the thin 1-0 lead he’d inherited and earning himself the win. The Trenton Evening News called him “the amazing retread who was unwanted by the major leagues just a year ago and now is one of the top right-handers in the league.”22

The moves the Red Sox had made, though, paid off in 1967; they won the pennant.

In 1968, the Yankees gave Monbouquette the opportunity to work as a starter again, and he got off to a very good start with five wins through the end of May and a 3.14 ERA. One of them was in long relief, though, throwing eight innings of two-hit ball in Oakland on April 23. Then he lost three games in a row in June and a fourth on the first of July, and saw his ERA climb to 4.43. The Yankees traded him on July 12 to the San Francisco Giants for another veteran right-hander, closer Lindy McDaniel. “Monbo did a fine job for us,” explained Yankees manager Ralph Houk, “but we needed a short-relief pitcher much more than we needed a distance-reliever spot starter.”23

The Giants didn’t use him much at all. He pitched 12 innings in seven games (giving up four homers in the dozen innings) and was 0-1. On December 21, the Giants assigned him to the Houston Astros on a conditional basis. He pitched in spring training for Houston, but didn’t make the team and had to start looking for a job. On April 9, the Yankees gave him a position as a scout and as a minor-league manager, working for their Appalachian League (rookie league) team, the 1969 Johnson City Yankees.

As a major league batter, Monbouquette didn’t hit much, just .103 in 701 plate appearances (.173 on-base percentage). He drove in 18 runs. One of his at-bats was of historic significance; in September 1965, he was the last major leaguer struck out by Satchel Paige.

He pitched 78 complete games, finishing his career with a 114-112 record (3.68). “My makeup was you had to finish what you start. Even with the greatest reliever I ever saw—and that was Dick Radatz—I used to say to him, ‘If you don’t get him out, I’m going to kick your [butt].’ Here’s a 6-foot-6-inch guy, 270-pound guy. He said, ‘Get up in the clubhouse and crack me a Bud, I’ll be right up.’ And he’d go 1-2-3.”24 He struck out 1,122 batters and walked 462, only 2.1 batters per nine innings.

Looking back on his career, he still held himself to a higher standard: “I should have been a better pitcher. I look back at games I should have won and didn’t because I made a stupid mistake—usually the mistake of trying to pitch too fine. Sometimes you try to nibble the corners—guiding the ball instead of throwing it. That’s wrong; you should be going with your strength.”25 He acknowledged that Fenway Park was a tough place to pitch, with its short left field and the lack of foul territory. “Overall, though, I believe Fenway makes you a better pitcher. You think more, you concentrate more.”26

The Johnson City team came in second in their division. The Yankees made a scout out of Monbouquette, using him for special assignments and crosschecking during 1969 as his Appalachian League schedule permitted and assigning him the southern New England territory starting in 1970. He worked as a scout for the Yankees through 1975.

In January 1976, he was named manager of the New York Mets’ Single-A Midwest League club at Wausau, Wisconsin. That December, he became the Mets’ minor-league pitching instructor. During the offseasons, he was in the retail liquor business.

Monbouquette also served two stints as major-league pitching coach for the New York Mets in 1982 and 1983, and (after a stretch working for the Yankees at Fort Lauderdale) for the Yankees in 1985 and ’86. He worked for the Yankees at Albany, too.

He worked teaching pitching at the minor-league level, working for the Toronto Blue Jays in their system—at Myrtle Beach in 1988, for instance. He was recognized with World Series rings in 1992 and 1993, and then worked from 2000 through 2005 as pitching coach for the Oneonta Tigers, Detroit’s Single-A team in the New York-Penn League. At the end of the 2005 season, he announced his retirement.27

In 2000, he was named to the Red Sox Hall of Fame. After the Red Sox won the World Series in 2004, they were very generous in the number of rings they gave out. One of them went to Bill Monbouquette.

Monbouquette’s first marriage ended in divorce. Monbo’s obituary in the New York Times tells how he got married a second time, to Josephine Ritchie. She was “born down the street from him in Medford, and she turned him down for a date when he first asked her as a teenager. They met again at their 40th-anniversary high school reunion and married in 2005.”28

As a Red Sox player, he was a regular supporter of the Jimmy Fund and frequently visited young children receiving cancer treatment, originally at the urging of teammate Ted Williams. When his battle with leukemia began in 2007, Monbouquette was treated at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, which saved his life with a stem cell transplant in 2008.

He battled leukemia for more than seven years, but ultimately died in Boston on January 25, 2015, from complications of the disease. He was survived by Josephine and three children—Marc, Michel, and Merric—as well as three grandchildren.

Notes

1 Boston Braves Historical Association Newsletter, Fall 2003, 3.

2 The Sporting News, February 29, 1964.

3 Boston Globe, July 15, 1958.

4 Author interview with Bill Monbouquette, August 24, 2014.

5 Boston Globe and Boston Traveler, May 28, 1953. The same day’s Boston Herald noted his 6-0 win, but called it a four-hitter.

6 Boston Traveler, June 16, 1954.

7 Boston Herald, September 11, 1955. One of his losses was a 4-3 loss, in which he gave up just one earned run.

8 Christian Science Monitor, August 6, 1958.

9 Author interview with Bill Monbouquette, April 17, 2009. Monbo remembered being at a banquet in San Antonio during a stint in the service, and Del Baker was at the same event. “He never even said hello to me. That didn’t bother me. I told Ted during spring training, “I thought this was supposed to be a team.” He said, “You’re right.”

10 Boston Globe, May 13, 1961. Nolan Ryan broke the night-game record in 1974.

11 The Sporting News, May 24, 1961.

12 The Sporting News, November 26, 1966.

13 Jon Goode, Boston Globe, July 16, 2004.

14 Stan Grossfeld, Boston Globe, May 16, 2008.

15 The June 14, 1965 Boston Globe tells the story of their meeting and marriage.

16 Boston Herald, October 5, 1965.

17 Ibid.

18 Boston Globe, October 5, 1965.

19 The Sporting News, November 26, 1966.

20 Boston Herald, January 8, 1967.

21 Boston Globe, May 11, 1967.

22 Trenton Evening News, April 29, 1968.

23 Boston Herald, August 1, 1968.

24 Stan Grossfeld, Boston Globe, May 16, 2008.

25 “Where Are They Now?”, Boston Scorebook, 2nd edition, 1981.

26 Ibid.

27 Oneonta Star, August 27, 2005.

28 New York Times, January 27, 2015.

Full Name

William Charles Monbouquette

Born

August 11, 1936 at Medford, MA (USA)

Died

January 25, 2015 at Gloucester, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.