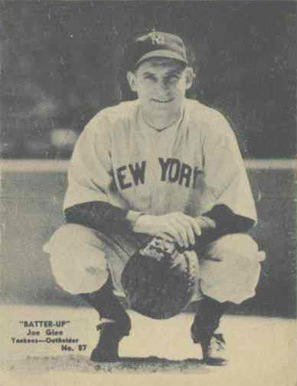

Joe Glenn

Name the catcher who caught both pitcher Babe Ruth and pitcher Ted Williams in regulation major-league ballgames. That’s a decent trivia question. The two sluggers are best known for their batting, but Williams did pitch in one game, on August 24, 1940.

Name the catcher who caught both pitcher Babe Ruth and pitcher Ted Williams in regulation major-league ballgames. That’s a decent trivia question. The two sluggers are best known for their batting, but Williams did pitch in one game, on August 24, 1940.

“My greatest claim to fame was striking out Rudy York with two men on,” Ted wrote in his autobiography. “I gave him a good sidearm curve, it broke about a foot, right over the plate, and he took it. I guess he didn’t know what to expect, whether I would throw it over the backstop or what.”1 Joe Glenn had also caught Babe Ruth, when Glenn was a catcher for the New York Yankees. Ruth broke into baseball as a pitcher, and in his later years he pitched very occasionally. The last game in which he pitched was on October 1, 1933, a complete-game 6-5 win over the Red Sox at Yankee Stadium, on the last game of the season. The catcher was Joe Glenn.

Glenn was born as Josef Guzensky on November 19, 1908, in Dickson City, Pennsylvania.2 His father, also Joseph, was a coal miner. He and his wife, Helena (Majewski), were of Polish ancestry and raised five children in Dickson City, near Scranton. Joe was the oldest boy. He went to the Woodrow Wilson and Lincoln schools, and then to Dickson City High School for two years. Even as a youngster, the Yankees were his team.

Glenn was primarily a pitcher in high school but, like most pitchers in school, played other positions when he wasn’t on the mound. He also played semipro ball around Dickson City and, at least for a while, for the team at St. Thomas College in Pennsylvania (not as a student, but playing on the team.)3 He worked in the coal mines, “taking my baseball where I could find it. You know you can’t even play night ball underground. … Then one day I heard the Syracuse team of the N.Y.P. League was going to play in Scranton the next Sunday.”4 He and a friend hitchhiked to Scranton and directly approached manager Mike O’Neill.

“I thought then that I was a pitcher,” Glenn was quoted as saying. “I had pretty good speed but couldn’t always tell where the ball was going. I started several games for Syracuse but went wild after a few innings, and Mike [O’Neill] had to take me out. He asked me one day, ‘Did you ever catch?’ I told him I used to fool around in most all the positions in high school. Anyway, he handed me a catcher’s glove and told me to see what I could do with it. The next day I bought myself a mask and all other catching paraphernalia. From that time on I was a catcher.”5

Burr’s story says that Glenn didn’t really even know how to stand properly on the pitcher’s mound.

Baseball made a huge difference in Joe Glenn’s life. After working in the coal mines, he had taken a job in a foundry. “For hours each day I had to stand over a fire … and poke at molten lead. That job pulled down my weight and scorched my eyes so much I decided there must be easier ways of earning a living.”6

His playing weight is listed at 175 pounds; Glenn was 5-feet-11, and right-handed.

Glenn’s first year was 1928. He’d broken in initially with the New York Penn-League’s Harrisburg Senators but was let go after an initial trial. His season’s-end stats are shown only in the final listings of the Syracuse Stars. It’s possible that any pitching starts Glenn may have had were in spring training; no pitching is reflected in the season summary. He shows only as a catcher – last in the league in fielding (.910) and near the bottom in hitting (.150, in an even 100 at-bats).

By this time, Joe had already adopted his “Americanized” surname. “It’s easier to pronounce and fits better in a box score,” he later explained.7 He played under the name Glenn, but never legally changed his name. His signing is credited to Yankees scout Paul Krichell.8

In the 1929 season, Glenn played 97 games with Hazleton (the Syracuse franchise had folded), batting .296, and then was sent to Jersey City by the Yankees, where he hit .265 in 14 games. He followed the same pattern for the same two teams in 1930. He still struggled defensively, committing 21 errors in 47 games for Hazleton. In 1931 Glenn played the full season with the Albany Senators, hitting .298 in 114 games. He improved dramatically behind the plate, making only 19 errors in nearly three times as many chances for a .970 fielding percentage.

In 1932 Glenn played for four different teams, three of which led their respective leagues. He started the season with the Newark Bears, appearing in about a dozen games, and then was transferred to the Eastern League’s Springfield (Massachusetts) Rifles. The Bears finished in first place in the International League.

The Eastern League disbanded on July 17 (with Springfield in first place at the time). Glenn was batting .340 when the team folded. The Yankees sent him to Newark, where he played in at least one game, on July 31, but when the Yankees assigned Eddie Phillips to Newark, Glenn was transferred to Binghamton. He appeared in 35 games there, batting .292. Later, he was called up to the Yankees themselves. The Yankees won the American League pennant and then swept the Chicago Cubs in the 1932 World Series.

Glenn made his major-league debut on September 15. He was 0-for-3, with a strikeout and a walk. He caught again on the 16th, and got both his first and second base hits (and was hit by a pitch). They were his only two hits that year; he appeared in six games and had 16 at-bats.

Right after the World Series, Glenn married hometown friend Estelle Moreiko on October 15. The two had three children, Joseph, Patricia, and Geraldine. Son Joseph was named Joseph Vernon Gurzynski, his first name said to be in honor not of his father but of Yankees manager Joe McCarthy, and his middle name in honor of Vernon “Lefty” Gomez.9

There had been some feistiness exhibited in May of the 1932 season, when Glenn threw his bat and a punch at Hartford pitcher Pat Stamey, who he claimed had tried to bean him after surrendering a single, double, and a home run to center field, “one of the longest clouts ever seen at League Park.”10 Police were needed to break up the fracas that followed. Glenn faced a suspension and fine.11

During spring training 1933, he joined a catching staff of Bill Dickey and Arndt Jorgens. Joe McCarthy thought two catchers might suffice so Glenn was assigned to Double-A Minneapolis on April 4. He hit .333, with 17 homers, in 137 American Association games, and was called up again to New York in September. He appeared in five big-league games, with three hits in 21 at-bats.

The Yankees used their final option in February 1934, sending Glenn to Newark. He spent the full year in Newark, with 12 homers and a .265 batting average and.978 fielding percentage.

In 1935 Glenn made the Yankees, stuck with them all season long, and may have saved the life of a woman in October. Glenn was third in the depth chart behind future Hall of Famer Bill Dickey and Arndt Jorgens. He got into 17 games, handling 62 chances with only one error, and batting .233.

After the 1935 season, in Scranton on October 26, Glenn was walking along the street and came across a burning apartment building. He learned that there was a woman trapped on the third floor and rushed in to assist her to safety before the firemen arrived.12

Of the six seasons in which Glenn appeared in Yankees games, 1936 – when he played in 44 games – totaled the most. He had 150 plate appearances and hit for a .271 average. He also hit the only home run of his Yankees years, on May 31 against Lefty Grove of the Red Sox. Lou Gehrig homered for New York as well, and the Yankees won, 5-4. In 1937 and 1938 combined, Glenn appeared in 66 more games. All told, over the six seasons, he got into 138 games for the Yankees, batting .252 with 56 RBIs and hitting the one home run.

Glenn played in two particularly memorable games during 1938 – on April 28, in front of what he said was the largest crowd in Yankee Stadium history, he “gave them something to remember – I hit into a triple play.”13 (Actually, there were fewer than 11,000 patrons – but it was a game-ending triple play, in the bottom of the ninth inning.) And on August 27 that year, he caught Monte Pearson’s no-hitter against the Cleveland Indians.

Bill Dickey played for the Yankees from late 1928 through 1943, spanning Glenn’s entire tenure with the team as one of Dickey’s understudies. The Yanks were in four World Series during Glenn’s years, but Dickey handled all the duties and Glenn never saw postseason play.

On October 26, 1938, Glenn was traded to the St. Louis Browns with outfielder Myril Hoag for pitcher Oral Hildebrand and outfielder Buster Mills. Ed R. Hughes of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote that Glenn was “a good boy … a good young catcher … who did not get much chance with the Yankees, for Bill Dickey was working most of the time.”14 It wasn’t as though Glenn hadn’t been of interest to other teams. As far back as mid-1935, Connie Mack had said, “I want Glenn” – but he wasn’t willing to give up a whole lot to get him. Mack continued, “But the way I will take him is by paying the waiver price. I would never think of letting any of my regular players go for Glenn but I will keep on holding up waivers on him this year, next year and the year after that.”15

The Yankees got “an experienced pitcher in Hildebrand and neither of the two players they gave is likely to be missed.”16 Buddy Rosar filled Glenn’s role as understudy.

As for Glenn, he finally had the opportunity to become the first-string catcher for a big-league club, albeit the last-place Browns. He appeared in 88 games and hit .273, a few points above the team average. He had impressed the Red Sox by homering twice in the July 28 game against them.

Ballplayers were paid only for the months they played, and almost all of them took offseason jobs – when they could find them, which wasn’t always easy during the Depression. The country was coming out of the hard times in 1939, but Glenn realized he could qualify for unemployment compensation and so applied for $15-per-week benefits – which he then planned to donate to the St. Mary’s parish church in Dickson City. Understandably this raised a few eyebrows, but Monsignor Stanley Szpotanski of St. Mary’s said, “Joe promised to help us with every dollar he secured. He felt as long as he had it coming, and we needed money urgently, it would be serving an excellent purpose. I don’t think Joe should be criticized for attempting to do a good turn.”17

Glenn was a holdout for 1940, incurring the wrath of Browns owner Donald Barnes, who proclaimed himself “thoroughly out of patience” with Glenn.18 Glenn appealed to Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis for help resolving the salary dispute. Barnes had been shopping him around, and finally found a taker on April 25, when the Red Sox purchased his contract. The Chicago Tribune put a needle in its headline on the AP story: “Now Joe Glenn Can Hold Out On the Boston Red Sox.”19

Red Sox manager Joe Cronin realized Glenn hadn’t put in any time during spring training and wouldn’t be ready to go right away, but allowed as how “We merely felt that picking up an experienced catcher at this time would bolster our catching staff for the flag fight ahead. It’s a long season and anything can happen.”20 A month later, Glenn got into his first game, and played in 22 total games for the Red Sox, all but two of the 22 in the months of June and July (and, lastly, the August 24 game in which he caught Ted Williams). The Red Sox had been hoping he might hit something like the .273 he’d hit for the Browns; he did not – he hit .128 (6-for-47).

Glenn played for Boston’s Double-A team in Louisville in 1941, for the Oakland Oaks in 1942, and for the Yankees affiliate Kansas City Blues in 1943. When it seemed both Bill Dickey and Rollie Hemsley were going to be called to military service before the 1944 season, the Yankees bought Glenn’s contract and it looked as though he was finally going to get his chance to play regularly for them. Then he got a letter in the mail from the United States Navy.

From April 1, 1944, to November 17, 1945, Glenn served in the Navy. At one point a month after he’d been assigned to the Great Lakes Naval Training Center, a yeoman who worked in public relations for the athletics program sought out Glenn and had a hard time finding him. When he finally met Glenn, he said, “There’s no record of your even being in the Navy.” Then Joe told him, “Try looking for the name of Joseph Guzenski – that’s me.”21 He ended up working on the physical training staff.

After the war Glenn became manager for part of the season for the PONY League’s 1946 Lockport Cubs, for Martinsville and then Moline in 1947 (both clubs finished in last place), for the last-place Moline/Kewanee in 1948, for the second-place Stamford Pioneers in 1949, and lastly for the third-place Carbondale Pioneers in 1950. He occasionally played in some games, from 76 games with Lockport to only 11 with Moline.

After baseball, Glenn became an automobile salesman working for the Russell Motor Car Co. and, later, Burne Olds Co. in Scranton.

Glenn died on Monday morning, May 6, 1985, at his home in Tunkhannock, Pennsylvania, stricken in his sleep – on Sunday night, he had been inducted into the Northeastern Chapter of the Pennsylvania Sports Hall of Fame.22

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Glenn’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Ted Williams, with John Underwood, My Turn At Bat (New York: Fireside Books, 1988), 82.

2 There are several spellings of Glenn’s legal name among the various newspapers.

3 “Glenn, Albany Catcher, Liked By Yankee Club,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, August 27, 1931: 19.

4 Harold C. Burr, “Glenn Bearded Baseball Lion In Dugout Den,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 29, 1933.

5 Fred Lieb, “Cutting the Plate With Fred Lieb,” unidentified newspaper clipping dated March 15, 1933, found in Joe Glenn’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

6 J. Earl Chevalier, “Baseball A Sinecure In Opinion of Glenn,” Springfield Republican, June 19, 1932: 23.

7 Fred Lieb.

8 See, for instance, Richard J. Conners, “Yanks Send Youngsters to Help Bolster Albany,” The Sporting News, February 5, 1931: 7.

9 So explained Joe’s wife in a newspaper column published under her name. See Mrs. Joe Glenn, “My Hubby Plays Baseball,” New York World-Telegram, March 24, 1937.

10 “Rifles Sweep Agents Series,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, May 23, 1932: 10.

11 “McCann To Ask Leniency For Joe Glenn, Fighter,” Springfield Republican, May 23, 1932: 11.

12 United Press, “Joe Glenn, of Yankees, Saves Woman from Fire,” Trenton Evening Times, October 27, 1935: 26.

13 “Where Are They Now?” unidentified 1979 clipping in Glenn’s Hall of Fame player file.

14 Ed R. Hughes, “Yankees Ship Hoag to St. Louis Browns,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 27, 1938: 18.

15 Albert W. Keane, “Calling ‘Em Right,” Hartford Courant, June 17, 1935: 11.

16 John Drebinger, “Yanks Get Hildebrand and Mills From Browns for Hoag and Glenn,” New York Times, October 27, 1938: 29.

17 “Priest Defends Browns’ Glenn,” Boston Herald, January 29, 1940: 12.

18 “Barnes Blasts Catcher Glenn,” Atlanta Constitution, March 8, 1940: 25.

19 Associated Press, “Now Joe Glenn Can Hold Out On the Boston Red Sox,” Chicago Tribune, April 26, 1940: 21.

20 Gerry Moore, “Red Sox Get Catcher Joe Glenn,” Boston Globe, April 26, 1940: 24.

21 Unidentified May 4, 1944, clipping in Glenn’s Hall of Fame player file.

22 “Joseph C. Glenn,” The Tribune (Scranton, Pennsylvania), May 7, 1985: 7. See also Jerry Janowski, “Gehrig Gave Glenn ‘Gabber’ Monicker (sic) during Dicksonian’s Tenure With Yankees,” Mid-Valley News (Olyphant, Pennsylvania), October 21, 1993: 29. Glenn was known to be talkative.

Full Name

Joseph Charles Glenn

Born

November 19, 1908 at Dickson City, PA (USA)

Died

May 6, 1985 at Tunkhannock, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.