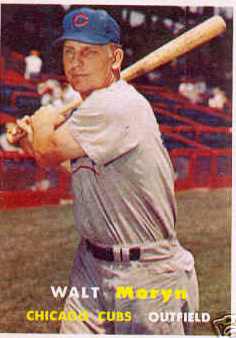

Walt Moryn

Chicago Cubs fans who are old enough will remember Walt Moryn as the blond, 6-foot-2, 205-pound Minnesota native who roamed the Cubs outfield from 1956 to 1960. The burly, left-handed-hitting slugger, known affectionately as “Moose,” averaged 20 home runs a season for a team that never won as many games as it lost. For most fans, however, Moryn will be remembered best for one outstanding moment in a Chicago uniform. It came on Sunday, May 15, 1960, when Moose made “the catch” that preserved a no-hitter for teammate Don Cardwell. The 33,543 people at Wrigley Field that day would never forget it, though some of them would exaggerate the difficulty of the game-ending grab. Moryn himself, for the rest of his life, would not be allowed to forget it, not that he would want to. His heroism that day was the culmination of four-and-a-half years as a Chicago Cub, seasons that were filled with the triumphs and disappointment that defined Walt Moryn as a major leaguer.

Chicago Cubs fans who are old enough will remember Walt Moryn as the blond, 6-foot-2, 205-pound Minnesota native who roamed the Cubs outfield from 1956 to 1960. The burly, left-handed-hitting slugger, known affectionately as “Moose,” averaged 20 home runs a season for a team that never won as many games as it lost. For most fans, however, Moryn will be remembered best for one outstanding moment in a Chicago uniform. It came on Sunday, May 15, 1960, when Moose made “the catch” that preserved a no-hitter for teammate Don Cardwell. The 33,543 people at Wrigley Field that day would never forget it, though some of them would exaggerate the difficulty of the game-ending grab. Moryn himself, for the rest of his life, would not be allowed to forget it, not that he would want to. His heroism that day was the culmination of four-and-a-half years as a Chicago Cub, seasons that were filled with the triumphs and disappointment that defined Walt Moryn as a major leaguer.

Walter Joseph Moryn’s parents, Edward and Sophie Moryn, were of Russian and Polish ancestry. Edward Moryn was born in St. Paul in 1899, the son of Russian immigrants. When he was 16 years old, Edward was riding in an automobile with some friends when the vehicle stalled in the middle of a city street. While the boys were attempting to restart the car, a passing streetcar struck the young Moryn, sending him to the hospital. Surgery and a lengthy recuperation managed to save his leg, but for the rest of his life Edward walked with a pronounced limp. The disability wouldn’t prevent him from earning a living working for the Omaha Railroad Company.

Sophie Dwuznik’s parents had emigrated from Poland, settling in St. Paul, where Sophie was born in 1906. She was working in a meat-packing plant when she married Edward Moryn in January 1924. Their first child, Mary Jane, was born in late 1924. Walter was born two years later, on April 12, 1926.

Walter’s family lived on the west side of St. Paul until he was about five years old, then moved to the Dayton’s Bluff area. They lived in an apartment above Johnson’s Grocery Store at the corner of Earl Street and Hastings Avenue (now Hudson Road). According to his sister, Walter played baseball all day and into the night. “Baseball was his love,” recalled Mary Jane. “I would even play with them when they needed players. He’d sneak out of the house to play baseball.”

The Moryn children attended St. John’s grade school and went on to Harding High School, where Walter excelled in football and basketball in addition to baseball. He graduated in 1944, much to the surprise of his sister, Mary Jane. “School didn’t interest him. When I was doing homework, he’s out playing baseball,” she said.

Walt Moryn had other things on his mind, however. He told Ed Prell of the Chicago Tribune that he enlisted in the U.S. Navy even before he had received his high-school diploma. He trained as a gunner’s mate and served more than two years on an ammunition ship in the South Pacific during the final stages of World War II.

When he left the Navy, Walt was barely 20 with no real sense of where his life was headed. He began taking courses to learn the tool and die trade. Meanwhile, he was playing some amateur baseball with the St. John’s church team in an industrial league. He also played in a softball league.

In August of 1947, Moryn was invited to a Brooklyn Dodgers tryout camp in St. Paul. He had been spotted by part-time Dodgers scout Gerry Flathman, who worked as a St. Paul city parks official. Scout Andy High supervised the tryout and recommended that Brooklyn sign Moryn. In later years, Moryn told Jerome Holtzman of the Chicago Tribune that he attended the tryout on a lark. But his sister felt differently. “He really hoped he would make it,” she said.

After signing with the Dodgers, Moryn’s first assignment was in 1948 with Class D Sheboygan of the Wisconsin State League, where he played for manager Joe Hauser, the legendary minor-league slugger. Eventually, Walt would come to appreciate Hauser’s avuncular nature and benefit from his relaxed approach to discipline. But at first there was some question whether the young Navy veteran had made the right career choice.

“I just couldn’t hit, maybe because I was pressing,” Moryn told Prell. “After about two weeks I was taken out of the lineup, and Hauser put an infielder in right field. I told him I could at least catch a ball, even if I couldn’t hit. I didn’t know it at the time, but he had decided I’d never do.”

It wouldn’t be the last time management would cast doubt on Moryn’s abilities. Throughout his career, Walt was seemingly always on the verge of getting benched. His perceived inability to hit left-handers made him a constant candidate for platooning. Moryn’s defensive skills were a frequent concern. And then, like all power hitters, he would occasionally fall into the dreaded slump.

Unfortunately, this particular slump was coming at the start of a career, and it might have been back to the tool and die had not help come from an unlikely source. Joe Hauser’s wife had taken Walt under her wing. “Mrs. Hauser was wonderful to me and the other young players,” Walt told Prell. Apparently, she had put in a good word or two with her manager-husband, and Hauser reinserted Moryn in the Sheboygan lineup. “It was in the middle of the season that she told me she had told Joe that I’d be a good ballplayer. Her urging saved me from getting fired.”

Moryn would go on to bat .338 at Sheboygan with 12 homers and 123 runs batted in (RBIs) in 124 games. He added 23 doubles and 11 triples in addition to 23 stolen bases, making for a rather auspicious professional debut for the 22-year-old Minnesotan.

Life in the Brooklyn Dodgers organization had its pluses and minuses. On the one hand, Branch Rickey had just begun the Vero Beach experiment that would become Dodgertown. Moryn’s first experience there was a memorable one. “We slept five or six to a room and many a night killed spiders and snakes in our bunks,” Moryn recalled. On the other hand, there was the competition to get noticed in the clamorous circus that was spring training in Florida. “Seven hundred players were in camp and, though I was discouraged, I said to myself, ‘Walt, you’re a long ways from home. You might as well give it a whirl.’”

The real challenge for Moryn, despite his sparkling season at Sheboygan, was not just to get noticed. After all, the Class D Wisconsin League is a far cry from Brooklyn. The road to Flatbush was going to be long and tedious. But once there, how would an ambitious farmhand ever manage to break into a lineup of National League champions? Along the way, with stops in Danville, Mobile, Montreal, and finally, serendipitously, hometown St. Paul, Moryn honed his skills and began to acquire a reputation as a slugger. Back-to-back seasons in the Southern Association at Mobile in 1950 and 1951 produced some big power numbers, including 24 home runs and a league-leading 148 RBIs in 1951, with 63 extra-base hits.

Still, Moryn’s climb up the ladder through the International League (Montreal) and the American Association (St. Paul) seemed headed toward a glass ceiling. “The Dodgers just had too much talent,” Moryn told Chicago sportswriter Jerome Holtzman. “They had Carl Furillo in right, and there wasn’t any room for me or anyone else.” With Duke Snider and Sandy Amoros, Brooklyn’s outfield was settled.

Spring training in 1954 did not go so well for Moryn. He simply couldn’t hit. Andy High, by then the Dodgers’ head scout, said that Walt was hitting the ball “off his knuckles,” resulting in popups and grounders. Roscoe McGowen, in The Sporting News, wrote, “Moryn [is] the last man training camp observers would have expected to make the Dodgers this year—or perhaps in any year. . . . Despite his size and strength, the springtime scribes never had seen him give any demonstration of good hitting in exhibition games.”

So it may have been a surprise when Moryn was called up to the Dodgers from St. Paul on June 27, 1954. “He’s a different hitter now,” High said. Walt had been hitting well for the Saints: 18 homers and 50 RBIs with a .301 average in 71 games. Perhaps it was the home cooking; Moryn’s folks had purchased a house on the east side of St. Paul in the Five Corners area, and Walt lived at home during his time there.

New Dodger manager Walter Alston said he only wanted a left-handed pinch-hitter off the bench, but almost immediately an injury gave Moryn his chance. In the 10th inning of a game against the New York Giants at the Polo Grounds, Snider was hit in the elbow by a pitch from Marv Grissom and had to leave the game. Moryn went to right field and Furillo moved over to center. In his first at-bat Walt grounded a single through the right side of the infield. That first week he contributed a four-hit game, including two doubles, against the Phillies. Then, on July 5, in Pittsburgh, Walt hit his first major-league homer, a two-run shot off right-hander Johnny Hetki. The blast, which capped another four-hit effort, was described in The Sporting News as “Ruthian.” The ball landed “more than halfway back into the upper stands” at Forbes Field and hit with such force that it bounced back onto the field. At that point, Moryn was 12-for-25 as a major league hitter. By the All-Star break, he was still batting .400.

Moryn also showed off his arm that first week. On July 4 in Philadelphia, with the Dodgers nursing a 1-0 lead in the sixth inning, Willie Jones tried to score from second base on a single off the bat of Stan Lopata. Walt, in left field, threw Jones out with plenty to spare. “I still haven’t touched the plate,” Jones said after the game, also crediting Roy Campanella with effectively blocking his path. The Sporting News described Moryn as “a pretty good outfielder with a strong arm.”

Walt’s bat cooled off the second half of the 1954 season, and his playing time was limited. He finished with a .275 average in 91 at-bats, with two homers and 14 RBIs. The Dodgers, defending National League champions, trailed the pennant-winning Giants by five games at year’s end. Brooklyn’s players recognized Moryn’s small but solid contribution by voting him a half-share of second-place money.

Those who thought that Moryn’s 1954 season was a sign of things to come for him and the Dodgers had miscalculated. For Moryn, 1955 proved to be a season of spinning his wheels and waiting for a trade that couldn’t come soon enough.

Except for a brief couple of weeks at the beginning and the end of the 1955 season, Moryn spent the entire year at St. Paul, where he soldiered on, hitting 25 home runs and driving in 88 but batting just .248. One highlight for the Saints, if it could be called that, was a third-inning single that spoiled Omaha pitcher Stu Miller’s bid for a no-hitter on September 3 (it was the only hit off him). His time in Brooklyn was limited to 11 games and only 19 at-bats. His September call-up was a perfunctory one; he could watch the Dodgers celebrate their first World Championship from a distance, but that was all. He wasn’t really a part of it.

So, when on December 9 it was announced that the Dodgers and the Chicago Cubs had engineered a trade that sent Don Hoak and Moryn to the Cubs for third-baseman Randy Jackson, it marked the beginning of a new and promising chapter in Moryn’s career. (Later, the Dodgers sent Russ Meyer to the Cubs in return for Don Elston as part of the deal.)

“When they traded me to the Cubs I was happy because I knew I had a chance to play in the big time,” Moryn told Ed Prell in the Chicago Tribune in 1958. “It’s too bad I didn’t get to Chicago earlier because I think I was ready before 1956.”

Evidence for that assertion was spotty, but very soon Moryn would show that he indeed belonged in a major-league lineup every day. At the time, those involved in the trade would only allow that Moryn was little more than a toss-in. Wid Matthews, the Cubs’ general manager, claimed that the deal was basically Hoak for Jackson. But he did give Walt his due. “Moryn can hit one a mile,” Matthews said. “His average at St. Paul was only .248, but that figure looks a lot heftier when you take his power figures into account.”

The Cubs were treading water in the National League. They hadn’t seen the first division since 1946, and there was no one area that required immediate attention; they were springing leaks everywhere. Only at shortstop, where Ernie Banks seemed to be a fixture, did they look solid. Matthews liked the volatile Hoak’s prospects at third base. He was a holler guy who might ignite a fire under his teammates. But going into spring training in 1956, Moryn still seemed to be an afterthought.

The first indication that he might make a positive contribution to the Cubs’ ledger came in April in the annual two-game, cross-town exhibition against the White Sox. In right field for both games, Moryn put on a hitting exhibition, cranking out seven hits and blasting two home runs. Shortly after, The Sporting News named him “one of the hottest young prospects” in baseball. Maybe only Walt saw the irony: he was already 30 years old.

One man who saw potential in the big Minnesotan was the Cubs’ long-time equipment manager, Yosh Kawano. He took one look at Moryn and was reminded of another left-handed Chicago slugger of recent vintage, Bill Nicholson, who had twice led the league in homers during World War II. “I decided he might be another Big Nick,” Yosh said, “so I gave him Nick’s old number.” Moryn would wear uniform No. 43 for two seasons with the Cubs before switching to No. 7.

The Cubs had traded Hank Sauer, their aging outfield hero, on March 30, making room for Moryn in right field if the Moose could capitalize on the opportunity. He did, almost immediately. Moryn was the one shining light in an otherwise dreary outfield picture for the Cubs. Just before the All-Star break, Walt was hitting .281 with nine homers and 31 RBIs. Chicago manager Stan Hack rotated outfielders Pete Whisenant, Monte Irvin, Eddie Miksis, and Jim King through the lineup trying to find someone else who could hit, with little success. “If we could just get one of them going to help Moryn along a bit, we’d notice the difference immediately,” Hack said.

It was around this time that Chicago fans began picking up on Moryn’s nickname. When and where “Moose” became attached to Walt’s name is probably lost to history. His 6-foot-2, 205-pound frame certainly had something to do with it, as perhaps did the fact that he came from the North Country. He had been known to his Dodger teammates as “Moose,” but it was only when he began playing regularly with the Cubs that fans at Wrigley Field, and then increasingly around the league, originated the “Moose” calls. Other players, Bill Skowron and Walt Dropo, for instance, had been known as Moose. But it was the alliterative power of “Moose Moryn” that grabbed hold in Chicago.

At first, those listening on the radio assumed that Moryn was being booed. Cubs announcer Jack Quinlan claimed to have received hundreds of letters from fans questioning the boos. “That’s the Moose call,” Quinlan would explain on the air. “It goes like this—’C’mon Moooooooose!’”

Much was made in the Chicago press of Moryn’s long, wavy blond hair, long certainly compared to the style of the day when even bankers were sporting crewcuts. There was at least one newspaper reference to him as “the Blond Adonis,” a nickname that, perhaps fortunately, never caught on. But more than two years before a young Bobby Hull established himself as the Blackhawks’ Golden Jet, Moryn was setting the pace on the Chicago tonsorial front.

Moryn ended up leading the 1956 Cubs in games played with 147, finishing the season with 23 home runs, 27 doubles, 67 runs batted in, and a .285 batting average. He demonstrated the strength of his right arm by leading all National League outfielders with 18 assists. Moryn’s contribution, however, wasn’t enough to keep the Cubs from losing 94 games and finishing in last place. It didn’t help that Ernie Banks suffered an injury and missed 15 games at midseason. After three seasons as manager, Hack was fired. In fact, the organization cleaned house, also firing general manager Wid Matthews. Before he left, Matthews revisited the subject of the trade that brought Moryn to the Cubs. “Moryn alone made the trade a success,” Matthews said, although some in the press were grumbling that giving up Jackson was too steep a price.

Over the winter, The Sporting News gave a terse verdict. Moryn was “no speed demon but he has power to spare, judges a fly ball well and no one takes advantage of him on the basepaths. He’s a good team man, well-conditioned always, and a good competitor.”

The new Cubs management team, John Holland in the front office and Bob Scheffing as field manager, were elevated by owner P. K. “Phil” Wrigley from the Los Angeles Angels farm club. It was reputed that they worked well together. In the beginning, it looked like some changes were in store, especially for Moose Moryn. The team wanted to emphasize speed, and, to that end, in spring training Moryn was tried out at first base. Moose had played the position very sparingly in the minors, but he was willing to take instruction from Cubs vice president Charlie Grimm, a long-time standout at first base. When that experiment foundered, Moryn was shifted to left field, where his slowness afoot might not be so noticeable.

While still in spring training, Scheffing unloaded his initial assessment of Moryn. He wasn’t happy with Moose’s defensive abilities. “I’m just trying to find a place where he can catch a baseball,” Scheffing told the reporters at an exhibition stop in San Antonio. “He told me he could play first base and he couldn’t. Then he told me he could play left field and he couldn’t. Frankly, I’m not even impressed with his work in right field and he hasn’t helped us much with his bat. But that doesn’t mean Moryn won’t play ball with us this season.”

Scheffing’s announced solution was to use the left-handed-hitting Moryn in a platoon system; he would play against right-handers but against only certain lefties. The manager claimed to have numbers that showed Moryn couldn’t handle left-handers. Overall, the statistics were on Scheffing’s side. Moryn was a .219 lifetime hitter against southpaws, .239 for the 1957 season. The next year, the average would plummet to .205. But Moose wasn’t happy. He told Ed Prell it was “strictly mental” and he called it “malarkey” that he couldn’t hit left-handers. “I keep in mind that the lefty’s curve is breaking away from me and that the right-hander’s curve is coming toward me. Once you get this in your mind, you have the problem licked.”

Moryn nevertheless played regularly at the beginning of the 1957 season. He was in right field for the opener in Wrigley Field, going 0-for-3 against southpaw Warren Spahn in a 4-1 Cubs loss. But two weeks into the season he was hitting just .200 with one extra-base hit. The Cubs were 3-7 and in last place when they visited Walt’s old team, the Dodgers. The Moose broke out of his slump with two doubles, a walk, and his first and only major-league grand slam, a seventh-inning blast off reliever Clem Labine that gave the Cubs a 9-7 lead. Chicago, however, blew the lead and lost, 10-9, in 10 innings.

In late June, during an 11-game span, Moryn hit .457, slammed five homers, and drove in 18 runs, raising his average for the season from .256 to .303. Now Prell, writing in The Sporting News, called Moryn “a steal” in the Randy Jackson trade. From that point on, Scheffing couldn’t keep Moose out of the lineup.

Another torrid streak in late July elevated Moryn into a tie with Banks for the club lead in RBIs at 56. Walt’s average continued to hover around the .300 mark. During the second half of the season, Moose ran off 14- and 19-game hitting streaks. Veteran pitcher Sal Maglie mentioned Moryn as one of the five or six batters in the league he’d least like to face. Cincinnati lefty Don Gross would agree after facing Moose on August 16 at Wrigley Field. The Cubs had blown a five-run lead when Moryn came to bat in the 12th inning with the scored tied 6-6. With a man on base and one out, he hammered a home run off Gross to send 10,000 fans home happy.

A home run Moryn hit into the right-center field bleachers at Wrigley Field that summer created a mini-controversy. After the game, the Moose admitted it was a handle hit and “besides, the bat broke.” In his column in The Sporting News, Oscar Ruhl used the incident to argue that the baseballs were “souped up.” Apparently, Ruhl didn’t consider that Moryn was strong enough to muscle the ball out of the park, rabbit or no rabbit.

The Moose was the subject of The Sporting News feature column on September 18, complete with a caricature cartoon—something he would never have warranted in his Dodger days. Jerome Holtzman wrote the article, calling Moryn “one of the NL’s foremost power hitters.” Holtzman even put a gloss on Moose’s lack of foot speed: “He seldom gets a cheap hit. Almost all of them are line shots that whistle over the infield.” But the major revelation came when Scheffing confessed that he had been wrong about Moryn. After revealing that Moose was on the trading block until early June, Holtzman quoted the Cubs manager: “He’s proved to me that he’s one of the most underrated players in baseball. I’ll always want him to play for me.”

The amicable feelings were mutual. Moryn credited Scheffing with freeing the slugger to hit the ball where it was pitched. “That’s one of the things I like about Scheffing, he said. “Bob told me that I don’t always have to go for the long ball. I find it’s better that way.” Seven of Moryn’s homers that year were to left field. “I’m looking the pitches over a lot more than I used to,” he continued. “I’m relaxed now and I’m getting more confident all the time.” Finally, Scheffing noted Moose’s ability with two outs and in clutch situations. “To me that’s the best sign of a good hitter,” he said. “He’s best when we’ve got men on base.”

Holtzman’s article closed with a quotation from general manager John Holland: “We’re going to build with the Moose.”

The final 1957 statistics showed Moryn with 88 RBIs and 19 homers in 149 games, with an average of .289, a career best. He reached career highs with 164 hits and 33 doubles. He added 13 outfield assists but committed 12 errors. In several ways, it was Moose’s best season. Yet the Cubs again trailed the rest of the league in the standings, and despite finding a couple of young pitching phenoms in Dick Drott and Moe Drabowsky, the team was still struggling for respectability.

The 1958 season was the high-water mark for the Cubs and Moose Moryn. The team escaped the cellar and, led by Ernie Banks, established a club record for home runs. Moryn contributed a career-best 26 home runs and earned selection to the All-Star team for the only time in his career.

The 1957-58 offseason had been sprinkled with trade rumors involving Moryn. The Giants were interested and floated offers, suggesting the Cubs might be willing to part with their slugger. Meanwhile, Moose was hinting that he might not be satisfied with the contract he had been tendered. The previous year, Cubs owner Phil Wrigley had instituted a radical merit-pay scheme that would reward players in-season for meeting certain performance goals. The Sporting News, in praising the plan, pointed out that ballplayers had always suffered financially by being paid “this year for what they did last year” and cited Moryn as one of the Cubs who benefited from Wrigley’s largesse. Now, the Moose expected to see that recognition reflected in his 1958 salary.

Moryn told Jim Enright of the Chicago American on January 8 that he had yet to sign his contract: “Considering the way I clicked in Mr. Wrigley’s incentive plan last year, I’m not expecting any trouble getting a sizable increase. I certainly wouldn’t ask for it if I didn’t think I earned it.”

Moose also reacted to Scheffing’s proposal to again move him from right field to left. “I don’t care where the skipper plays me as long as I get my three or four swings every game, every day,” Walt told Enright. “I’ll play left, or right, or take tickets in the bleachers if it means I get my regular turns at-bat.”

The Cubs had traded for Lee Walls during the previous season. Now Walls was penciled in as the right fielder. Scheffing let it be known that he felt Moose’s arm wasn’t what it once was. Moryn issued one caveat: “I told him, ‘Bob, you’re the boss, and I’ll play any position you pick for me.’ I did warn him, however, about the perils of playing right field in Wrigley Field. It’s the toughest sun field in the league, and whoever he picks had better be hep to both the sun and the tricky winds.”

Walls would end up playing most of the year in right, and Bobby Thomson, acquired in a trade in April, would patrol center. Moryn became the Cubs’ regular left fielder. He was one of the heroes when Chicago mounted one of its greatest comebacks in years. With the Cubs trailing the world champion Milwaukee Braves 7-0 on May 2 at Wrigley Field, Moose got one back with a solo homer off Gene Conley in the sixth inning. Chicago chased Conley in the seventh and tied the game with a six-run rally. Then in the ninth, with one out, Moryn came to the plate against left-hander Dick Littlefield and drove a home run to right field for a dramatic 8-7 victory.

On Memorial Day 1958, the Cubs hosted the Los Angeles Dodgers in a doubleheader in front of a full house of more than 37,000 fans. In the crowd that day was Sophie Moryn, watching her son play for the first time in the big leagues. In the opener, Johnny Podres took a 2-0 shutout into the ninth when, with one out, Walls homered to cut the lead in half. After the second out, Ernie Banks walked, and the southpaw Podres faced Moryn. Moose lined a double to left, scoring Banks with the tying run. Podres was replaced by Ed Roebuck, and, after an intentional walk, Sammy Taylor singled to center as Moryn raced home with the winning run.

The second game of the twin bill was even more eventful. Don Newcombe started the game for the Dodgers and was handed an early 6-0 lead. But the Cubs fought back. Down 7-1 in the fourth inning, Banks and Moryn slugged back-to-back home runs to cut the margin to 7-3. Moose’s homer was a towering drive into the left-center-field bleachers. Three Cubs runs in the sixth made it 7-6 before Los Angeles scored once in the top of the seventh. Then in the home seventh, Moryn homered to right off Roebuck, and Chuck Tanner followed with a roundtripper to tie the score 8-8. The score was still knotted when Sandy Koufax relieved for the Dodgers in the ninth. Banks led off by drawing a walk, bringing Moryn to the plate.

The Moose had popped up twice and homered twice. He was facing the lefthander Koufax, not yet the most formidable pitcher in the game but certainly one of the most intimidating. The first pitch was a fastball and Moryn swung and missed. Koufax then wasted a curve and Moose shortened up as if to bunt. Koufax came back with a fastball with the count at one-and-one. Moryn was waiting for it and drove his third homer of the game into the left-center field seats, scoring Banks ahead of him, sending Koufax and the Dodgers to a 10-8 defeat, and giving the Cubs a holiday sweep.

“It was the first time in my baseball career I ever hit three homers in one game,” Moryn told the Chicago Daily News after getting a big hug from his mother. Manager Bob Scheffing was delighted with the offensive production from his leftfielder. “I’ve maintained all along that when Banks and Moryn both hit at the same time we’ll score a lot of runs. They proved that, didn’t they?” Scheffing also asserted that the fake bunt set up the pitch Moryn wanted to see. “We wanted him to get a fastball to hit,” the manager said. “That’s why we had him bunting on the second pitch.”

The All-Star Game was to be played in Baltimore on July 8, and for the first time in several years the players, managers, and coaches would be voting to select the non-pitchers for the game. Moryn finished second to the Pirates’ Bob Skinner in balloting for the left-field spot. The American League won 4-3, but the Moose failed to get into the game.

The Cubs staged another dramatic comeback on July 14, and Moryn was one of the heroes. Trailing the Phillies 9-5 in the ninth at Wrigley Field, the Cubs tied the score, but Philadelphia took the lead with a run in the top of the 11th. In the bottom of the inning, Ernie Banks and Sammy Taylor delivered one-out singles to bring Moose to the plate. He doubled into the gap in left-center off Ray Semproch as the tying and winning runs scored.

Games like that were still a rarity in Chicago, however. The Cubs were actually 43-41 after the victory over the Phillies, 2½ games out, in third place. But it was a success that would prove impossible to sustain. Dick Drott and Moe Drabowsky had each pitched more than 200 innings the previous year, and their young arms failed to hold up in 1958. They both suffered from the overwork. The team, in addition, was slow and made a lot of errors. After the respectable start, the Cubs finished the season at 72-82 in a tie for fifth place.

The only real bright spot was the hitting. Banks won the first of his two straight Most Valuable Player Awards by leading the league in homers, RBIs, slugging percentage, and total bases. Moryn’s contribution paled by comparison but still was impressive. His average fell off to .264, but the Moose’s 26 home runs, 26 doubles, seven triples and 77 RBIs reaffirmed his status as a premier slugger in the National League. He scored 77 runs, another career best. And he ran off a 14-game hitting streak in early September during which he averaged .393. Along with Banks’s 47 homers, Moryn’s total combined with Lee Walls (24), Bobby Thomson (21) and Dale Long (20) to help set a team record of 182 home runs that would stand until 1987.

Perhaps for the first time in his career, Moryn arrived for spring training in 1959 confident of a full-time position in a major-league lineup. His abilities were being recognized around the league. A March 25 letter to The Sporting News called Walt “probably the most underrated player in the majors today.” Scheffing had him penciled in as the Cubs’ regular left fielder. Only a pessimist would have noted that by the first week of the season Moose would turn 33.

In May, Moryn married Ruth Resnick in a ceremony attended by many of his Cubs teammates. It wasn’t until July, however, according to The Sporting News, that Moose and his bride bought a one-acre tract in Deerfield, Illinois, where they planned to build a home. No matter how secure he felt after three years in a Cubs uniform, Moryn would wait until after the trading deadline before he committed to a major land purchase in the Chicago area.

There were indications in 1959 that Moryn had earned a reputation as a tough, burly guy who was not to be trifled with. His size was always a factor to be taken into account even for teammates who had no reason to fear his wrath. In a game in San Francisco on April 16, the Cubs were ahead 4-1 in the ninth inning when Ernie Banks walked and Moryn followed with a double, sending Banks to third. Dale Long hit a ground ball to second baseman Daryl Spencer, who booted it momentarily. When Spencer recovered, he looked up to see Moryn heading for third. Banks, however, had hesitated. He told reporters after the game, “All I could think of was to get out of the big guy’s way. So I headed for home.” Banks and Moryn both scored when Spencer threw the ball wildly past third for his second error on the play. The Cubs went on to score seven runs in the inning on their way to an 11-3 victory.

A more serious physical confrontation occurred April 30 in Cincinnati when Moryn and his roommate, Dale Long, fought off three hoodlums around 2:00 a.m. outside of their hotel. Two cab drivers witnessed the incident in which Long apparently dispatched one attacker with a single punch, and the Moose fended off another by pinning his arms together. A year later, in his book, Baseball Is a Funny Game, Joe Garagiola put Moryn on his all-star team of “best fighters in a brawl.” Oscar Ruhl, in his column in The Sporting News, had already recognized Moose as a fellow who could handle himself “fistically.” Mostly, it seems that other players went out of their way to avoid Moryn should tempers flare on the field or off.

Hank Sauer had been impressed with the Moose during the brief time the outfielders were teammates in 1956. “I know one thing,” Sauer said at the time. “We’ll challenge any two guys on the club to a fight. And I’ll just watch, because Walt is big enough to take care of both of them.”

But the Moose was doing little hitting with his bat. The previous August, he had been helped out of a minor slump when Reds slugger Ted Kluszewski suggested a heavier bat. Moryn had been swinging a relatively light 33-ounce model. Kluszewski recommended he move up to 36-ounce lumber. That seemed to work then, but now nothing seemed to help. On July 20, Moose was hitting .219. The next day he hit a double and his ninth homer in an 8-2 win over St. Louis, but he was out of the lineup the day after that against a left-handed pitcher. It would be August 14 before he hit another home run.

Some of the Moose’s troubles were caused by a mouth infection diagnosed as gingivitis. The malady was sapping his energy, causing backaches and headaches, and forcing him to miss some games. It was only after the season that it was revealed that he underwent oral surgery during the All-Star break to correct the problem. Originally, his dentist advised Moryn to wait until the offseason, that the procedure would require at least six weeks to heal. But the pain was becoming unbearable, so Moose elected not to wait.

Meanwhile, the Cubs were flirting with .500 ball. They were getting excellent pitching from youngsters Glen Hobbie and Bob Anderson and some surprising efforts from American League castoff Art Ceccarelli. With Ernie Banks terrorizing the rest of the league’s pitchers, the Cubs were again in the unusual role of contender. They were just 5½ games out of first place on July 21.

But manager Bob Scheffing was playing Moryn less and less. On any given day the Cubs might have Bobby Thomson in left field, or perhaps journeymen Art Schult or Irv Noren. They were also taking a look at a young rookie named Billy Williams. Moryn sat on the bench during back-to-back doubleheaders August 20 and 22 in Philadelphia and Milwaukee, then went 0-for-4 on August 23. He started games only three times in a two-week span toward the end of August, finally hitting his 11th homer, off Don Drysdale, on September 6. He hit another home run on September 9 in the second game of a doubleheader after going 0-for-5 in the opener. Six days later he hit number 13, off Bob Gibson. Moose’s batting average was at .245.

Perhaps it was frustration over his batting woes that led Moryn to go public with his unhappiness. But when he complained August 27 to John Kuenster of the Chicago Daily News that general manager John Holland was dictating the Cubs lineups to Scheffing on a day-by-day basis, he opened up a media hornet’s nest. Kuenster warned Moose that what he was saying, if aired, might jeopardize his job. “I don’t care,” Moryn said. “The way they’ve been using me, I’m not much good to them anyhow.” He claimed Holland was the one who was keeping him out of the lineup. And, Holland, he said, was responsible for creating a negative atmosphere by playing high-stakes poker with some of the players on road trips and spending his off-days at the race track.

“I don’t think [owner Phil] Wrigley knows what’s going on,” Moryn told the Daily News. “Maybe this is one way he’ll find out. [Holland’s] the guy who runs the club, not Scheffing.” Perhaps looking to the future, Moose promised Kuenster a bigger scoop if and when he was traded.

Moryn’s tirade followed a similar critique from his roommate, Dale Long, who had also seen his playing time decreased. On September 9 in The Sporting News, Jerome Holtzman addressed the issue, first by getting Moryn to pretty much retract what he had told Kuenster and then by getting Holland and Scheffing to respond. Holland denied everything and Scheffing defended his boss. Then Holtzman quoted Wrigley: It was “disgruntled players who were having bad years.” The owner did allow that “$100 poker stakes” were out of line.

But Holtzman concluded by quoting an unnamed Cubs veteran: “I think Mr. Holland is going to be pretty busy when they have that inter-league trading. What’s it like in the American League, anyway?”

Walt Moryn had his worst full season as a Cub in 1959, with 14 home runs, 48 RBIs, and a .234 average in 117 games. Still, the Cubs closed out the year with 74 victories and a second straight tie for fifth place. It represented their best back-to-back seasons since 1945-46. Ernie Banks hit 45 homers, drove in 143 runs, and won another MVP Award. Other signs pointed to better days ahead. Yet, on the day after the campaign ended, Phil Wrigley fired manager Bob Scheffing and his entire coaching staff.

Why Scheffing was relieved of his job has remained a mystery, but there was much speculation in the press at the time. Scheffing himself said he expected a raise and a new contract, so it was a complete surprise when Wrigley told him he was being replaced with 61-year-old Charlie Grimm, a pennant-winning Cubs manager in the long-ago past and currently a team vice president. “I’ve always thought we should have relief managers, just like relief pitchers,” the owner said, perhaps foreshadowing his “college of coaches” scheme that would be rolled out two years later.

Chicago Tribune columnist Dave Condon thought Scheffing was a scapegoat, that he was basically taking the fall for John Holland’s shortcomings. Moryn’s criticisms had hinted that Scheffing and Holland were not the smooth-running team they once were, if indeed Holland was writing the lineups. In any event, dissension in the ranks was not a good thing, it was out in the open, and Moose Moryn was principally responsible for putting it there.

Moryn may have been convinced that he was living on borrowed time in a Cubs uniform, but he diligently began preparing for the 1960 season. His wife had given birth to their first child, Michelle Jo Anne, on December 28, and Moose considered himself a true family man now. He arranged to report to spring training 10 days early in order to get down to his playing weight. As a rookie he had played at 205 pounds; now he was closer to 215 or 220. Moryn admitted that he was only now beginning to shake off the effects of the oral surgery back in July. Again, he told The Sporting News, the complications from the infection and the surgery had left him “tired and listless,” and prone to weight gain. He knew he had been sub-par for most of the 1959 season. He was certain 1960 would be better.

Over the winter the Cubs traded away Lee Walls and Dale Long and also dealt some of their younger prospects. They acquired veterans Richie Ashburn, Don Zimmer, and Frank Thomas. Thomas, a right-handed-hitting left fielder, would be competing with Moryn for playing time.

The first week of the season, Moose was on the bench in San Francisco when Grimm called on him to pinch-hit with two outs in the eighth inning against Sam Jones. The one-time Cubs right hander was working on a 6-0 lead and needed just four more outs to record his second career no-hitter. Moryn broke it up in spectacular fashion by launching a home run to deep right field. “I think I did Sam a favor by ruining his no-hitter,” Moose told reporters after the game. “Often after a no-hitter a pitcher goes bad.” Jones retired the last four Cubs to complete the one-hit game and was left to mull over Moryn’s remarks, whether they were humorous or patronizing.

Walt Moryn’s destiny with no-hitters was not ended, however. But first the Cubs front office had more moves to make. Wrigley stunned everybody by ending the Charlie Grimm experiment just three weeks into the season. To replace the manager, the Cubs called on Lou Boudreau, former Indians, Red Sox, and Athletics helmsman, who was currently working as a color analyst for the team’s WGN radio affiliate. Grimm took over for Boudreau in the announcer’s booth. (After a seventh-place finish in 1960, Boudreau asked for a two-year contract, was turned down, and returned to the radio booth, where he stayed until the late 1980s.)

On May 13, the Cubs traded Tony Taylor, a popular young infielder, and catcher Cal Neeman to Philadelphia for first-baseman Ed Bouchee and right-handed-pitcher Don Cardwell. On balance, the Phillies would get the better of the deal. Taylor would go on to a long and successful career while Bouchee would be gone the next year. Cardwell had some success with the Cubs through 1962, but he later went on to pitch well for the Pirates and the Mets. For those looking for immediate dividends, however, the Cardwell acquisition would be hard to surpass.

May 15 was a Sunday and the Cubs were hosting the Cardinals in an afternoon doubleheader. St. Louis won the opener 6-1 behind Larry Jackson’s complete-game performance. Moryn raised his batting average to .333 with two hits plus a pair of walks. Moose was in left field again in the nightcap when Cardwell faced off against Lindy McDaniel.

Cardwell retired Joe Cunningham leading off the game, then walked Alex Grammas. From that point on, he set down 23 Cardinals in a row, getting to the ninth inning with a no-hitter intact. The Cubs scored once in the fifth, Ernie Banks hit a two-run homer in the sixth, and the team added another run in the seventh inning to make it 4-0. Meanwhile, using mostly his fastball, Cardwell had struck out seven while thwarting a lineup that included Ken Boyer, Bill White, and a young Curt Flood. He closed out the eighth inning with a flourish, striking out pinch-hitter Stan Musial.

Now, in the ninth, Cardwell faced two more pinch-hitters. Throwing nothing but fastballs, he got Carl Sawatski on a long fly ball to the wall in right field and George Crowe on a medium-deep fly to center. That brought up Cunningham, a pesky, left-handed slap hitter who seldom failed to make contact. The count reached 3-and-2 and Cardwell came right down the middle with another fastball. Cunningham slashed a low liner to left, a drive that looked certain to spoil Cardwell’s bid for baseball immortality. But Moryn was positioned well, not playing too deep for the singles-hitting Cardinals first baseman. Moving like a runaway freight train, Moose charged in and grabbed the ball ankle-high in one hand, then just kept running to join the rest of the Cubs in the no-hit celebration near the mound.

Cubs television announcer Jack Brickhouse called it this way: “There’s a drive on a line to left field . . . come on, Moose . . . he did it, he did it. Moryn made a fabulous catch and it’s a no-hitter, a no-hitter. And what a catch that Moryn made. Oh brother, what a catch he made!” In later years, it would sometimes be described as a diving catch, but the memory can play tricks. Moryn never tried to embellish the moment—”[I]t was just a matter of do or die,” he said once. “I figured to give it a shot.”—but it was a difficult catch to make. There was no margin for error, and the late afternoon shadows at Wrigley Field could play havoc with a fielder’s vision and judgment.

As a hitter, Moryn had passed his peak. He hovered around the .300 mark for the next four weeks, but his power swing seemed gone. On June 12, he was hitting .287 with two homers and 11 RBIs. Boudreau was playing him regularly, and the Moose would bang out two or three hits once or twice a week, then go 0-for-4. On June 15, at the trading deadline, the Cubs sent Moryn to St. Louis for minor-league infielder Jim McKnight and some cash. The Moose took the opportunity to rip into Cubs general manager John Holland. “He has been trying to get rid of me for three years,” Moryn told the Chicago Tribune. “Frankly, I never thought I’d make it to spring training.” The Tribune raised the possibility that Holland made the deal over Boudreau’s objection. All the manager would say was “I like Moryn . . . he gave me 100 percent.”

Many years later, Jim Brosnan, the pitcher-turned-author who had played with Moose from 1956 to 1958, told author Peter Golenbock that Moryn was a chronic complainer on a team full of malcontents. “Walt Moryn still gripes about everything,” Brosnan said. “He gripes about leaving the Dodgers and coming to the Cubs, where he was a star. He couldn’t make the Dodgers, but he gripes because he could have been on a World Series team.”

Nevertheless, the departure of Moryn to the Cardinals left an emotional hole for the Cubs and Chicago. The Tribune noted that the Moose was as popular with his teammates and fans as any Cub since Hank Sauer. His four-and-a-half years with the club, during which he put up some sizable offensive statistics, earned him respect and admiration second only to Ernie Banks. He had made Chicago his home for himself and his family. Now it was all over.

His first game in a Cardinals uniform was less than scintillating. Moose went 0-for-5 and struck out four times. He would eventually regain his footing in St. Louis with 11 home runs and 35 RBIs in 200 at-bats for a team that finished in third place, nine games out. He hit .448 in August as the Cardinals briefly moved into second place. But for Moryn, it was the beginning of the end. The next June, after appearing in only 17 games with St. Louis, he was sold to Pittsburgh for cash and a minor leaguer. Moose’s final major-league action came with the Pirates, where he hit three homers in 40 games and 65 at-bats, mostly as a pinch hitter.

Moryn’s final major-league career record stands at 101 home runs, 354 RBIs, and a .266 average in 785 games. He had 116 doubles, 16 triples, and a slugging percentage of .446.

After baseball, Moryn went to work for his in-laws’ department store in Villa Park, Illinois. He managed the sporting goods section, selling fishing tackle and hunting gear. Walt and Ruth Moryn divorced in the late 1960s, and he eventually remarried. He and his second wife, Carolyn, had a daughter, Kelly, in 1970. Moryn later ran a tavern and liquor store in Cicero, Illinois. He retired in 1988 and devoted much of his time to a passion for golf. He played in several charity events in the Chicago area.

Moryn was relaxing at home in Winfield, Illinois, on July 21, 1996, when he suffered a fatal heart attack. He was 70. He had recently had a complete physical exam and was given a clean bill of health. “It was a shock to all of us,” his sister, Mary Jane, said.

Among those who remembered Moose was Cardwell, whose no-hitter was nearly overshadowed by the drama of the game-saving catch. “He made me famous,” Cardwell told Jerome Holtzman for an obituary in the Chicago Tribune. “After I threw the pitch, I was leaning down with him and saying, ‘C’mon, Moose, make the catch.’

“He was a good man, a ballplayer’s ballplayer. After the game I told him, ‘Moose, I owe you a beer.’ And he said ‘I’ll take you up on it.’ He enjoyed life. And he enjoyed people. He always drew the biggest crowd.”

Another Cubs teammate was fellow St. Paul native Jerry Kindall, who was just 21 when he first arrived in Chicago fresh from the University of Minnesota. Kindall told Holtzman about his first encounter with the Moose. “I walked into the clubhouse and there was Walt,” Kindall said. “He was wonderful to me. He shepherded me around. He gave the appearance of a very gruff guy, but if you were a teammate, you saw through that in a hurry. He was really a tender-hearted guy.”

Glen Hobbie recalled a shutout he pitched as a rookie for the Cubs in 1958 when Moryn scored early in the game to give him the lead. “When he got back to the bench,” Hobbie said, “he told me, ‘There’s your run! Hold ‘em!’

“And I did. He was the boss.”

A version of this biography appeared in SABR’s “Minnesotans in Baseball” (Nodin Press, 2009), edited by Stew Thornley.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Kelly Tomkowiak, Walt Moryn’s daughter, for her support and assistance in this project

Sources

Telephone interview with Mary Jane (Moryn) Hasselman, November 25, 2007.

Telephone interview with Carolyn Moryn, October 7, 2007.

Books

Castle, George, The Million-to-One Team: Why the Chicago Cubs Haven’t Won a Pennant Since 1945, South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, 2000.

Garagiola, Joe, Baseball Is a Funny Game, New York: Bantam Books, 1960.

Golenbock, Peter, Wrigleyville: A Magical History Tour of the Chicago Cubs, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996.

Palmer, Pete and Gary Gillette, The 2005 ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia, New York: Sterling Publishing, 2005.

Snyder, John, Cubs Journal, Cincinnati: Emmis Books, 2005.

Articles

Chicago American, “Moryn Willing to Play Any Position for Cubs,” James Enright, January 8, 1958.

Chicago Daily News, “Moryn Thrills Mother,” Howard Roberts, May 31, 1958.

Chicago Daily News, “Keeps Me on Bench—Moose,” John Kuenster, August 27, 1959, p. 43.

Chicago Tribune, “Moryn Not Only One Saddened by His Trade,” June 17, 1960.

Chicago Tribune, “The ‘Catch’ Moryn’s Defining Moment,” Jerome Holtzman, July 23, 1996, p. 3.

Chicago Tribune (Sunday Magazine), “Moose on the Loose,” Ed Prell, June 14, 1959, p. 46.

New York Daily News, “Dodgers Get Cubs’ Jackson In Swap for Hoak, Moryn,” Dick Young, December 7, 1955, p. C28.

The Sporting News, July 14, 1954, “Rookie Moryn Falls in Step With Dodgers’ Slug Parade,” Roscoe McGowen, p. 11.

The Sporting News, December 14, 1955, “More Roomers Than Rumors in Chi as Trade Talks Blow Up,” Carl Lundquist, p. 13.

The Sporting News, July 18, 1956, “Weak-Hitting Outfield Still Hobbles Cubs,” Ed Munzel, p. 6.

The Sporting News, January 9, 1957, “Bruins Step Up Campaign For Flyhawk,” John C. Hoffman, p. 10.

The Sporting News, April 17, 1957, “Baker Shines For Bruins in Shift to Third,” John C. Hoffman, p. 25.

The Sporting News, July 3, 1957, “Cubs’ Moryn and Banks in Hit Rampage,” Ed Prell, p. 29.

The Sporting News, July 24, 1957, “A Quick Pay Reward For Players,” p. 12.

The Sporting News, July 24, 1957, “Rabbit Kickback Breaks Moryn’s Bat,” Oscar Ruhl, p. 17.

The Sporting News, September 11, 1957, p. 7.

The Sporting News, September 18, 1957, “Bruins’ Moryn Turns into Bull-Moose Batter,” Jerry Holtzman, p. 3.

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Walter Joseph Moryn

Born

April 12, 1926 at St. Paul, MN (USA)

Died

July 21, 1996 at Winfield, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.