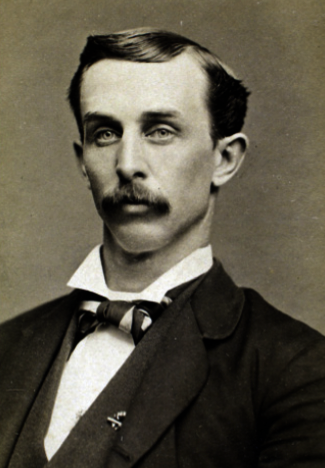

Dave Birdsall

“He was a faithful, conscientious player, who always worked to win and could always be depended upon.”1 To have something very complimentary said about you at your passing is gratifying, but the person who says it can be as telling about your life. This testimonial was made by 1870s star ballplayer (and future Hall of Famer) George Wright upon the death of Dave Birdsall, his friend of more than 30 years and teammate on both the original 1871 Red Stockings and the first Boston championship squad in 1872.

“He was a faithful, conscientious player, who always worked to win and could always be depended upon.”1 To have something very complimentary said about you at your passing is gratifying, but the person who says it can be as telling about your life. This testimonial was made by 1870s star ballplayer (and future Hall of Famer) George Wright upon the death of Dave Birdsall, his friend of more than 30 years and teammate on both the original 1871 Red Stockings and the first Boston championship squad in 1872.

David Solomon Birdsall was born on July 16, 1838, in New York City’s Lower East Side, to Solomon and Sarah Birdsall. He was the oldest of four children, with siblings Eliza Jane, John, and Sarah E. coming later. David’s father is listed as a policeman in the 1860 US census and in the few City Directories in which his name appears. By 1860 David had left the family and was working as a store clerk, living on Second Avenue in 1867, not far from his parents. It is likely he joined the base ball craze sweeping New York City in the 1850s, playing for various neighborhood teams. Officially Birdsall played one game in 1858 at second base for the Metropolitans.2 The 1890 Civil War Veterans Census indicates that David enlisted in the war effort in July 1861 and served four years as a private. Such duties seemed not to interfere with his occasional ballplaying; he “is first prominent with the Harlem team for three years” (1860-62), and the (Bronx) Unions of Morrisania in 1863.3 It was with Morrisania that Birdsall got his reputation as a dependable player. Through the 1860s he caught and pitched for the Unions as they slowly became a respected club. When position-player teammate Charlie Pabor started pitching in the mid-1860s, the Unions improved. In 1866 they compiled a 25-3 record, the same year cricketeer-turned-baseballist George Wright first crossed diamond paths with Birdsall. Wright played nine games for the Unions.

In 1868 infielder Wright played in all 43 Union games as did Birdsall – behind the bat. At 37-6 the Union amateurs ranked behind only the Athletics of Philadelphia (47-3) and New York Mutuals (47-7), while edging out Harry Wright’s Cincinnati Red Stockings by one victory. Morrisania had won 29 straight games before losing 13-12 to the pre-iconic Cincinnati Red Stockings in late August. Harry then coaxed brother George to Porkopolis to help create what became the unbeaten juggernaut Red Stockings of 1869 and most of 1870.

Birdsall also moved in 1869, taking his talents to the Washington Nationals, who finished 13-13 but were only 4-12 against the best amateur clubs.4 The Wrights and Cincinnati (57-0) beat the Nationals 24-8 in June 1869; Birdsall managed one hit. At age 32 Birdsall returned to his Morrisania mates in 1870 and caught 18 games in their 20-19 season (7-18 versus “professional” teams). He met his old friends the Ohio River Wrights on June 15. Asa Brainard surprisingly shut out the usually strong Unions, 14-0. It was the day after the Red Stockings’ extraordinary win streak had been suddenly snapped by the Brooklyn Atlantics, 8-7 in 11 innings. In Brainard’s “chicago” win, Birdsall had one of the five Union hits, walked twice and lined into a double play started by his quick-handed pal George Wright.

Having shown his worth playing with and against the Wright brothers, it is no surprise that when the signings for the new professional league were announced in late January of 1871, Birdsall was inked with the Boston club. The New York Clipper of January 28, 1871, under a story dateline of January 21, listed all team rosters to that date.5 It was the day after Ivers Whitney Adams held his Parker House lunch, announced his grand intention of fielding the finest team in the new National Association and asked some deep-pocket friends to buy stock in it. Starting with manager Harry Wright and his stellar brother George, down to Birdsall, all were in the fold before there was an actual team. It is not difficult to figure that because George and Harry knew of Birdsall’s worth firsthand, they picked him as “insurance” for the Red Stockings roster. Twenty-five years later, at his death, Sporting Life surmised that Boston acquired Birdsall because of “his successful catching of the wild and swift left-handed Pabor” of Morrisania.6

Reasons for employing Birdsall might not have been that evident to the unschooled base ball masses. He was the second oldest Red Stocking (only player-manager Harry Wright was older) and had the slightest physical stature of anyone on the team. At 126 pounds, he did not have a catcher’s physique, but he had been a nimble and notable backstop his entire 12-year amateur career. Cincinnati right fielder Cal McVey would do the bulk of catching for the 1871 Reds, but resting him was of prime importance to the team, and Birdsall was key to that plan. Durable Dave caught the preseason games and most Reds exhibitions, giving McVey days off but allowing the club to make side money. Birdsall, who most often played right field, and Cal often traded positions in some one-sided Association games.

Birdsall batted third in front of cleanup slugger McVey in most of the 1871 games, and his hitting was a surprising plus for the Reds. Except for an early twisted ankle (missed two games), at 33 Birdsall held up well. With all the other better-hitting, younger players in the league, Birdsall (.303) finished second in runs scored (51) to teammate Ross Barnes (66) and third in team hits behind McVey and Barnes. A strategically rested McVey benefited greatly, leading the league in hits (66), finishing second to Athletic star Levi Meyerle in batting average, .492 to .431, and McVey was second in RBIs to New York Mutual pitcher Rynie Wolters, 44 to 43. But with shortstop George Wright injured for half the Reds’ games, the Scott Hastings contract fiasco (his NA Commission-determined ineligibility culminated in forfeits giving Philadelphia two wins in games they lost to Hastings’ Rockford, Illinois, club) and the blowing of four “safe” leads, the Reds finished second to Philly (20 wins to 21), dampening Birdsall’s productive season.

In the very first game, on May 5 in Washington (Olympics), Dave accounted for four runs in the 20-18 win, despite being struck out twice by loser Asa Brainard. On May 29 his four hits and four runs aided a 25-11 win over the Rockford Forest Citys. His “career high” day also came versus Rockford, when on July 10 his five hits and five runs off loser Bill “Cherokee” Fisher helped whip the host Westerners, 21-12. Back at the South End Grounds on September 2, Birdsall scored five runs on three hits against the hapless Cleveland Forest Citys, in a 31-10 victory.

Things changed a bit in 1872 as Birdsall began to wear down. He played in 16 of 48 games and hit just .211. But he was McVey’s energy-saving substitute again, catching two or three games each month, all exhibitions and the final innings of some slaughters, saving Cal from the continuous chore of catching Al Spalding’s speedballs. But reliable Dave still had his offensive moments. On May 9 Birdsall helped pound new Brooklyn Eckfords pitcher Jim McDermott, 20-0, with three doubles and three RBIs, a combined two-hitter for Spalding and Harry Wright. Later Birdsall contributed a run and an RBI to a ninth-inning rally that edged the tough Mutuals, 4-2. The Reds won the first 10 games he played in, giving them a 33-4 record. He caught the year’s finale, against the Eckfords, a 4-3 win for Spalding over Reds nemesis George Zettlein. Dave was an important cog in the first Boston championship season (39-8-1).

Birdsall might have retired in 1873 because of Association-wide faster pitching, but instead stayed on to help his club as best he could. Though much less evident, his “insurance policy” talent was again illustrated, as he caught most of the April exhibitions. It took two young “Jims” bound for stardom to replace him. McVey left Boston and new catcher James “Deacon” White (formerly of Cleveland, inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2013) needed time to get settled.

Birdsall started the first three games of the season and those were the last of the total 48 he played in official Association competition. The defending champion Red Stockings lost two of those first three games before Deacon White stepped in for good and helped capture a second straight NA championship. Bridgeport, Connecticut, native and 1872 Middletown Mansfield budding star James “Orator” O’Rourke replaced Birdsall in right field. Birdsall, however, was a fixture in moneymaking exhibitions throughout the year, playing in more than 20, catching in half of those. On occasion when the opposing team would be minus a player, stalwart catcher Birdsall would fill the toughest position for the amateurs, allowing the game to be played and the gate to be collected.

Birdsall’s final game with his Red Stockings comrades was one of spontaneous fun. In late December, Harry Wright assembled what was left of his team in wintry Boston, gathered some top local amateurs and announced in the Christmas Day Boston Daily Advertiser that there would be a game that morning at the South End Grounds, no admission to be charged. It was to be 10 innings with 10 players to a side. The temperature hovered at 34, and the wind was calm under a partly cloudy sky. On a hard, bumpy, but dry field the Wrights faced the Spaldings as the “pick up” teams battled to an 18-16 Wright brothers victory. The two winning runs appropriately scored in the intended 10th frame. Dave caught Spalding for the final time and scored three runs. Harry, George, and younger brother Sam Wright played with Bob Addy, Charlie Sweasy, and Jack Manning, while Spalding’s group included Birdsall, future National League Beaneaters owner Art Soden, Fred Cone, and Jamaica Plain baseball manufacturer Louis H. Mahn. About 500 hearty holiday souls attended.7

During the 1873 season, “impartial” Dave Birdsall was called upon to umpire one July game, in Brooklyn, as he and the Reds traveled with the Athletics from Philadelphia to Boston. The Atlantics beat the Athletics, 14-7. Choosing to remain a Boston resident, yet no longer a member of the team in 1874, Birdsall kept his hand in the game he loved by umpiring three South End games. Boston won two.

The 1880 US census has Birdsall at 222 Harrison Avenue with his wife and child. He had married a woman (Fanny from either Eastern Canada or Vermont) in 1872. Daughter Carrie (Caroline Sarah) was born on January 8, 1873. There is no Massachusetts record of the marriage or any clue as to what happened to Fanny. The daughter’s birth is recorded under Caroline “Bird.” At her birth the Birdsalls lived on Oxford Street (now part of Chinatown), before moving to 222 Harrison, where Dave would stay until his death.

Proudly listed with the “Boston Base Ball Club” in the City Directories of 1872 and ’73, Birdsall was a clerk starting in 1874 and for the rest of his working days. He was involved in several businesses, the first being with the Melodeon Billiard Hall, then owned by John Henry Flack. There were a dozen pool halls along lower Washington Street then, the Melodeon, a former theater, being the most lavish. Flack was a tournament player in Massachusetts who died suddenly in 1880. He owned a second billiard establishment at which Birdsall also worked.

Birdsall then briefly joined Elisha A. Holbrook at his billiard business before becoming employed by the Old Colony Railroad at its Kneeland/South Street depot/ticket office. In the mid-1880s he hooked up with Causeway Street liquor dealer John M. Benson. By 1894 and until his death, Birdsall was a clerk at 56 Kilby Street, Humphrey Dyer’s restaurant in bustling Liberty Square. Back during his 1870s billiard parlor days on Washington Street, Birdsall’s location was between the sporting-goods stores of both Wright brothers, so he likely saw them frequently.

Only six weeks prior to Birdsall’s death, Sporting Life reported that he had a “recent hospital stay and was hobbling around with the aid of a stick.”8 The prognosis of his “coming out all right” was wrong; Birdsall died on December 30, 1896, leaving his daughter. The New York Clipper ran a nice obituary lauding his playing career and adding that had Birdsall lived in pain since an operation in 1895.9 Birdsall was an Elks Lodge member, and was listed as one of the mourners, and perhaps an usher, at the funeral of baseball icon Mike “King” Kelly in November 1894, since the near-destitute King was buried by that organization.

Dave Birdsall is buried five headstones (15 feet) from Kelly in the Order of Elks Plot at Mount Hope Cemetery in the Mattapan section of Boston. A miffed Sporting Life writer complained that only two old ballplayers attended his funeral, local Jack Manning (1873 and 1875 Reds) and the Stockings’ only third baseman, Harry Schafer, who devotedly came up from his native Philadelphia. A Sporting Life blurb revealed that in 1871 both George Wright and Birdsall met Schafer in New York and they all boated up to Boston to begin training for their first Red Stocking season.10 Over the decades Birdsall’s daughter, Caroline, lived in Boston and Cambridge, working for a clock company until she died in 1951 in Allston.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Retrosheet.org, census information, city directories from Boston and New York, and numerous daily Boston newspapers.

Notes

1 “Another Veteran Gone,” Sporting Life, January 9, 1897: 9.

2 Marshall D. Wright, The National Association of Base Ball Players 1857-1870 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2000), 21.

3 Sporting Life, January 9, 1897: 9. The Morrisania section of the Bronx begins about 0.7 miles east of Yankee Stadium and is bound by Webster and Prospect Avenues (east to west) and 161st St. to 169th St. (south to north). It is less than a square mile.

4 Wright, 251.

5 New York Clipper, “Players Who Have Signed Papers,” January 28, 1871: 338.

6 J.C. Morse, “Recollections Awakened by the Death of Birdsall,” Sporting Life, January 9, 1897: 7.

7 “A Ten Inning Game,” New York Clipper, January 3, 1874: 315.

8 “Another Vet Gone,” Sporting Life, January 9, 1897: 9.

9 New York Clipper, January 9, 1897: 719.

10 “Recollections …,” Sporting Life, January 9, 1897: 7.

Full Name

David Solomon Birdsall

Born

July 16, 1838 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

December 30, 1896 at Boston, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.