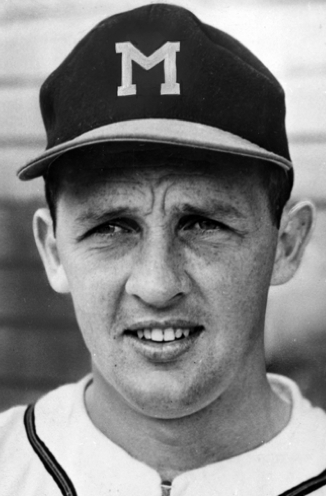

Ernie Johnson Sr.

A right-handed relief pitcher whose major-league career spanned the entire decade of the 1950s, Ernie Johnson retired with a lifetime record of 40-23 and an ERA of 3.77 in 273 games. “Maybe not the stuff of Cooperstown,” remembered Hall of Famer Eddie Mathews, a former teammate, “but damn it, the man could pitch.”1 Johnson’s even greater claim to fame, however, was as a television broadcaster for the Atlanta Braves His 52-year association with the Braves was the longest of any person in the organization.

A right-handed relief pitcher whose major-league career spanned the entire decade of the 1950s, Ernie Johnson retired with a lifetime record of 40-23 and an ERA of 3.77 in 273 games. “Maybe not the stuff of Cooperstown,” remembered Hall of Famer Eddie Mathews, a former teammate, “but damn it, the man could pitch.”1 Johnson’s even greater claim to fame, however, was as a television broadcaster for the Atlanta Braves His 52-year association with the Braves was the longest of any person in the organization.

The youngest of three children, Ernest Thorwald Johnson was born in Brattleboro, Vermont, on June 16, 1924. His father, Thorwald, and his mother, Alina “Inkie” Ingeborg, had emigrated from Sweden in the early 1900s. They were lured to Brattleboro by the Estey Organ Company, a world-famous manufacturer of pipe organs. With many Swedes among its 300 employees, Estey was one of the biggest employers in Vermont around the turn of the century, and the neighborhood where Ernie Johnson grew up, close to the Estey factory, was known as Esteyville. Ernie’s father worked at Estey for 45 years, and also delivered newspapers on Sundays during the Great Depression.

Johnson recalled that he sometimes went along on those delivery runs “just to be with my father and read the sports page.”2 The children of Esteyville were crazy for sports, and Ernie’s first paying job was caddying at the local golf course. “A caddie received 35 cents for nine holes and 60 cents for eighteen,” he remembered. He occasionally played a round when he was not caddying, but for the most part his free time was spent in neighborhood games of baseball, football, or basketball, depending on the season. “We played pickup baseball games over on the hospital grounds and neighborhood teams at Oak Grove School,” Johnson remembered. “We also played baseball and basketball teams at Austine School for the Deaf. I became friends with several of the deaf students” Growing up in Vermont, Johnson never played Little League baseball; in fact, the Little League field in Brattleboro was not built until 1952, ten years after he made his professional debut. Ernie’s first taste of organized sports came in high school. He always had above-average size and was a good all-around athlete, but most felt that his best sport was basketball. His father installed a hoop outside their house, and Johnson recalled that he and his friends played even in the snow.

Yale University was interested in Ernie as a basketball player. Even after he chose baseball as his profession, Ernie stayed in shape during winters by playing semipro basketball in Vermont and professional basketball in Connecticut.

According to most accounts, Johnson was merely an average baseball player until 1942, his senior year at Brattleboro High School. He actually lost his first game that season, 8-1 to a strong team from Greenfield, Massachusetts, but only one of the runs was earned. Ernie bounced back with a win in his next start, taking a shutout two outs into the ninth inning before yielding a two-run homer.

Johnson’s next three games comprise one of the most unusual pitching streaks in the history of high-school baseball in Vermont. On May 8 he pitched a one-hit shutout against Springfield. In his next game, against Bellows Falls on May 13, he pitched another one-hitter, this time taking a no-hitter into the ninth inning before giving up a single. Then on May 20 he took another no-hitter into the ninth inning in a game against Deerfield, Massachusetts. Again his no-hit bid was spoiled, this time by a pair of hits with one out, but he also struck out 20 in what was probably the best game of his high-school career.

For the 1942 season, Johnson pitched all but two of Brattleboro’s games, averaging 12 strikeouts, compiling a 6-3 record, a 1.09 earned-run average, and a .409 batting average, and leading the team with 13 RBIs. At the time, though, almost nobody thought he was a potential major leaguer. When asked about it years later, one of Johnson’s former teammates replied, “It never entered my mind or any of our other teammates’ minds. Baseball players from Brattleboro, Vermont, just don’t make it to the major leagues.”3 One man, however, thought differently. Ray Draghetti, Johnson’s coach at Brattleboro High School, believed his 6-foot-4, 180-pound pitcher had the size and talent to make the majors. After graduation, Draghetti took him to Boston for a couple of tryouts, as described in Bob Dubuque’s article in the June 19, 1942, edition of the Brattleboro Reformer:

“We haven’t been asleep, but just careful in not reporting that Ernie Johnson was down in Boston for a few days trying out with the Red Sox. It got pretty well noised around, but we wanted to wait until the kid got home again to find out what the story was.

“Ray Draghetti, who took Ernie to Boston yesterday to work out with the Braves, said the [Red] Sox were interested in the Brattleboro High School star and let him read the fine print on a contract, which he did not sign. The [Red] Sox wanted Ernie to stay home and put on some beef this summer and go south with them on a farm team in the winter. However, it would appear to be a summer wasted here since there is little prospect of semipro ball. That’s the story to date.”

One week after the tryouts, Casey Stengel’s Boston Braves gave Ernie the choice of traveling with the big-league team and throwing batting practice or signing a contract and reporting directly to the minors. He chose the former, and within ten days he was 100 miles from home, pitching batting practice to a team that included future Hall of Famers Paul Waner and Ernie Lombardi. Before his tryout with the Red Sox, Ernie had never been to a major-league game.

After 2½ weeks of traveling with the Braves, Johnson signed a minor-league contract, receiving $125 per month and a signing bonus of $100. The Braves sent him to Hartford of the Class-A Eastern League, for whom he made his professional debut on August 9, 1942. Johnson pitched in only eight games that summer, posting a 2-2 record and a 2.84 ERA, but one of them stood out in his memory: “My mom was a homemaker, a great mom. She went to Hartford once to watch me pitch and I gave up a three-run homer. The fans started booing. She turned to some of them and proudly said, ‘That’s my boy.’ They slumped down in their seats quietly.”

Before the 1943 season Johnson was drafted into the U.S. Marine Corps. He participated in the Okinawa invasion and was discharged as a staff sergeant in February 1946. His family liked to joke that America was losing the war when he entered the service and had won by the time he was discharged.

Johnson returned to Brattleboro in 1946. That winter, while attending a high-school basketball game, he first noticed Lois Denhard, a cheerleader. They were married a year later. “When we first met, she asked me what I did. I said, ‘Play baseball,’ and she said, ‘No, really, what do you do for a living?’ After she saw my first minor-league check, she asked again.” The next several years were like a roller-coaster ride for the Johnsons. After only one inning of work with Hartford in 1946, Ernie was demoted to Pawtucket of the Class-B New England League. Although he pitched adequately, as attested by his 3.95 ERA, Johnson was 4-7, one of only two losing records in his 14 years as a professional pitcher. He returned to Hartford and posted winning records in 1947 and 1948, and in 1949 he earned a promotion to the Braves’ Triple-A affiliate, the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association. After only 11 innings, however, the Braves demoted him to Class-A Denver. Undaunted, Johnson became one of the best pitchers in the Western League, and his 15-5 record and 2.37 ERA earned him a place on the all-star team.

The Boston Braves invited Johnson to spring training as a non-roster player in 1950. After giving up a home run to Ted Williams in an exhibition game, Johnson remembered manager Billy Southworth saying, “Don’t worry, kid, he’s hit ’em off better pitchers than you.” The resilient Vermonter surprised everyone by breaking camp with the big-league club. For the first time he was earning what he describes as “real money” – $5,000 a year.

Johnson made his major-league debut in Philadelphia on April 28, 1950, becoming the only player from Brattleboro ever to play in the majors. Although he pitched in only 16 games, he managed to hang on with the Braves for most of the season. Johnson was 2-0, but his 6.97 ERA probably accounts for his late-season demotion to Hartford.

The Braves sent Johnson to the minors again in 1951, this time to Milwaukee, but he refused to become discouraged. He went 15-4, led the American Association in ERA (2.62) and winning percentage (.789), and pitched the Brewers to the Governors’ Cup and a Junior World Series victory over the Montreal Royals. Including his five postseason victories, Johnson was a 20-game winner in 1951.

Johnson started the 1952 season with Boston, and this time he was in the majors to stay. Bothered by a sore arm, Ernie pitched mostly in relief and went 6-3 for the Braves. He also received 10 starting assignments and pitched a shutout in one of them – one of only three complete games he pitched in the major leagues.

For the rest of his career Johnson pitched almost exclusively in relief, which was surprising because as a starter his worst inning was usually the first. Also surprising for a reliever was that his best pitch was his palmball, which was designed to induce groundballs, not strikeouts. “He made my job a lot easier,” Eddie Mathews remembered. “His palmball would sink and it kept me busy.”

Before the 1953 season, the Braves left Boston, where they were always less popular than the Red Sox, and headed west for Milwaukee, where Johnson had played minor-league ball just two years earlier. It was the first change of cities for a major-league franchise in half a century, and the Braves’ success in Milwaukee guaranteed that it would not be the last. From 1953 to 1957, in the major-league city with the smallest population, the Braves averaged 2.1 million in attendance, almost doubling their nearest competitor.

Johnson remembered the euphoria of those early years in Milwaukee: “I’ve been in baseball for more than three decades, and I’ve never seen anything remotely close to Milwaukee in the ’50s. They were wild, incredible years. Nobody cared in Boston whether we lived or died. Then, in Milwaukee, the town went bananas. We couldn’t buy a thing – fans would give us everything free. The players were treated like royalty. Every day was a feast.

“The news of the shift had come in spring training down in Bradenton. When we went north to Milwaukee, they had a huge parade and we went downtown. When we got there, I’ll never forget how the people put up a Christmas tree – in April – inside the Schroeder Hotel. They were so beautiful. They said that since we’d missed Christmas with them, they wanted to celebrate it with us now. So there were hundreds of presents under the tree – shaving kits, toiletries, radios, appliances. Just ga-ga from the first day.

“It was like a small town. Some of us lived five minutes from the park. In those first few years we’d go around town, and even when we tried, we couldn’t pay for what we bought – the sponsors wouldn’t let us.” Johnson himself got off to a poor start to the 1953 season – so poor, in fact, that he thought he might be headed back to the minors. But things turned around, and in one stretch of seven days he received credit for three victories. He became a mainstay in the bullpen of a great Milwaukee pitching staff. His 35 relief appearances led the team, and his 2.67 ERA was second on the staff to Warren Spahn’s league-leading 2.10.

Johnson followed up that performance in 1954 by posting a 2.81 ERA in 40 games, establishing himself as one of the premier relief pitchers in baseball. Toward the end of that season the citizens of Brattleboro planned a special day in his honor which was recounted in Vic Harrison’s article “Toast for a Great Guy” in the Brattleboro Reformer.

Though the New York Yankees were the dominant team of the 1950s, the Braves, with future Hall of Famers like Mathews, Spahn, and Henry Aaron, more than held their own. The Braves won the pennant in 1957 and met the New York Yankees in the World Series. Johnson remembered the thrill of pitching in Yankee Stadium: “I remember walking to the mound and all I could think of was, ‘Son, you’ve made it. You’ve finally made it.’ God, I was so happy. I was walking with the ghosts of Ruth and Gehrig – me, just a kid who had lived and died baseball all his life.”

The Braves won the 1957 World Series in seven games, and Johnson played a major role. Pitching in Games One, Three, and Six, he gave up only two hits and one run in seven innings, striking out eight and walking one. The only run he gave up was a homer off the foul pole by Hank Bauer that proved to be the winning run in Game Six, but when asked if he thought it was a cheap shot, Johnson replied with characteristic modesty: “There was nothing cheap about that home run. He hit it so hard it may have bent the pole.”

After the World Series, Johnson returned to Brattleboro for a welcome-home dinner. He was billed as “Brattleboro’s Own World Series Hero,” and family, friends, and local dignitaries attended.4 Among them was Bill Jackowski, a National League umpire from nearby North Walpole, New Hampshire. A story has it that in one game Ernie complained to Bill about his calls on ball and strikes. Jackowski took off his mask and said, “This isn’t the West River Valley League in Vermont. Stop complaining and just throw the ball.” “That [story] may be true,” Johnson said, “but we both had great respect for each other. Billy once told me we were friends off the field, but on the field I don’t know you and it was understood that we both had jobs to do.”

The 1958 season was be Johnson’s last as a player in Milwaukee. Pitching in only 15 games, he once again had a winning record (3-1), but his ERA ballooned to 8.10. Before the season was over, the Braves, who were on their way to another World Series matchup against the Yankees, placed the 34-year-old Johnson on waivers. He remembered it distinctly:

“When the Braves got waivers on me in August, I guess the race was pretty well settled and nobody wanted to pay the $20,000 to claim me along with the salary. Then the Braves were very decent with me and let it be known that I could make my deal or stay with their chain, as I pleased. I know there were stories that I tried to land with the Giants and other National League clubs, but that isn’t so. The first man to call me when I was free was [Paul] Richards and I didn’t look further.”

Richards managed the Baltimore Orioles. Johnson spent his final year in the major leagues with Baltimore in 1959. He pitched respectably, compiling a 4-1 record and a 4.11 ERA, but the Orioles released him after the season. He signed with Cleveland, but arm troubles plagued him in the spring of 1960, and although he appeared on a baseball card that year with Cleveland, he never threw a pitch for the Indians. “They offered to send me to the minors to work things out, but I knew it was time to call it quits.”

Johnson returned to Milwaukee and hosted a television show called Play Ball, in which he and a guest sat around talking baseball and drinking milk. One of his first guests was Joe Garagiola. When Johnson told the affable catcher that he was nervous appearing on television, Garagiola told him to “just be yourself.” It was advice that worked well over the years for Johnson.

For a year Johnson handled the commentary on 20 Braves telecasts and also did some speaking on the banquet circuit, but his main job was selling life insurance for Northwestern Mutual. “I thought I’d be selling insurance the rest of my life,” he recalled. But in 1962 the Braves offered him a full-time job in the front office as an administrative assistant to team president John McHale, and Ernie accepted. “Being in the front office had always been my ambition,” he said. “From the time I broke into baseball, that was what I wanted to do rather than managing or coaching.”

Johnson’s job eventually evolved into that of a full-time broadcaster. He moved with the club to Atlanta after the 1965 season and was named Georgia Broadcaster of the Year in 1977, 1983, and 1986. He received three television Emmys. He retired as a full-time announcer at the end of the 1989 season.

Johnson’s popularity with Braves fans was never more evident than on September 2, 1989, when the Braves held Ernie Johnson Day. The attendance exceeded 42,000, the largest crowd for a Braves home game that entire season. During the pregame ceremony, Johnson received a television set from his fellow broadcasters, a satellite dish and annual use of a condominium in Florida from TBS, and an automobile from the Braves. He also received proclamations from the Brattleboro selectmen and the governors of Vermont and Georgia. “It was fabulous,” Johnson exuded. “… It was the greatest day I have ever had and it is something Lois and the whole family will never forget.”5

By 2000 Johnson was semiretired, living in Alpharetta, Georgia, and spending lots of time with his wife, three children (daughters Dawn and Chris are teachers, and Ernie Jr., following in his father’s footsteps, was a sportscaster for WTBS and on network sports), and seven grandchildren). He still called about 30 games a year on Sports South Network and substituted occasionally on TBS. Over his 32 years in broadcasting, Johnson worked more than 4,100 games, and through it all maintained his grace and gentle humor. For all of the home runs hit by Hank Aaron and knuckleballs thrown by Phil Niekro, nobody spread more goodwill for the Braves than Johnson. “I love baseball,” he once said, “and I think it shows.”

Johnson was inducted into five Halls of Fame: the Braves Hall of Fame, the Atlanta Sports Hall of Fame, the Georgia Radio Hall of Fame, the Georgia TV Hall of Fame, and the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame.

After an extended battle with congestive heart failure, Johnson died on August 12, 2011, in Cumming, Georgia. While going through the many passages from the online tributes Braves fans had posted about his father, Ernie Jr. read one that buckled his knees. It said, “When you heard Ernie Johnson do a game, it was like summertime would never end.”6

An earlier version of this biography appeared in “Thar’s Joy in Braveland! The 1957 Milwaukee Braves” (SABR, 2014), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. It was originally published in SABR’s

“Green Mountain Boys of Summer: Vermonters in the Major Leagues 1882-1993” (New England Press, 2000), edited by Tom Simon.

Sources

In researching this article, the author made use of Johnson’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, the Tom Shea Collection, the archives at the University of Vermont, and several local newspapers.

Notes

1 Atlanta Braves public relations department, no date. Johnson’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

2 All quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from the author’s interview with Ernie Johnson in 1993.

3 Author’s interview with high-school teammate Bob Ratti in 1993.

4 Vic Harrison, Brattleboro (Vermont) Reformer, no date, no page. Player’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

5 Ken Campbell, Brattleboro (Vermont) Reformer, September 5, 1989: 15.

6 Carroll Rogers, “Ernie Johnson, Jr., emotional, grateful, proud following death of his father,” Atlanta Braves with David O’Brien, http://blogs.ajc.com/atlanta-braves-blog/2011/08/13/ernie-johnson-jr-emotional-grateful-proud-following-death-of-his-father.

Full Name

Ernest Thorwald Johnson

Born

June 16, 1924 at Brattleboro, VT (USA)

Died

August 12, 2011 at Cumming, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.