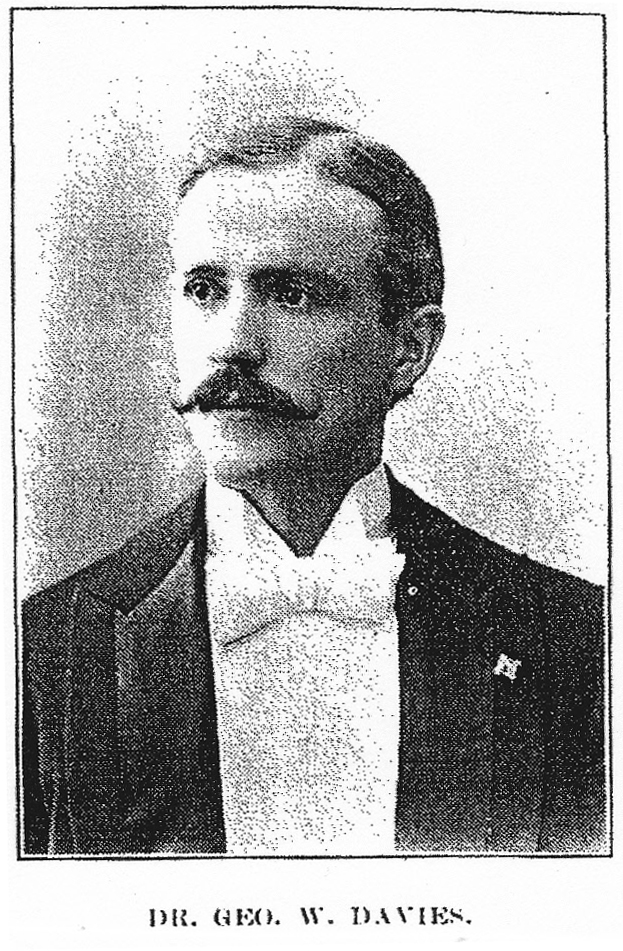

George Davies

By all outward appearances, George Davies was leading the good life in the early autumn of 1906. A dozen years removed from a short but respectable stint as a major leagues pitcher – he had won 10 games for the second-half pennant winning Cleveland Spiders in 1892 — Davies was now an eminent citizen of Waterloo, Wisconsin: an esteemed local physician, a member of various civic and fraternal organizations, and the happily married father of two young children. Family, friends, and neighbors were, therefore, stunned by the death of George Davies, found lifeless in his office on the evening of September 22, 1906. The 38-year old doctor had committed suicide.

By all outward appearances, George Davies was leading the good life in the early autumn of 1906. A dozen years removed from a short but respectable stint as a major leagues pitcher – he had won 10 games for the second-half pennant winning Cleveland Spiders in 1892 — Davies was now an eminent citizen of Waterloo, Wisconsin: an esteemed local physician, a member of various civic and fraternal organizations, and the happily married father of two young children. Family, friends, and neighbors were, therefore, stunned by the death of George Davies, found lifeless in his office on the evening of September 22, 1906. The 38-year old doctor had committed suicide.

An inquest concluded that the cause of death was an overdose of Bromidia, a powerful sedative.1 If the coroner’s jury further determined what caused this sad act of self-destruction, it saw no need to publish it. All that found its way into newsprint was that “the death of George W. Davies is deplored by a large circle of friends. He was himself a friendly man. His nature was genial, his attachments strong. His keen wit and bright intellect made him welcome in every circle. … The entire community extends a heartfelt sympathy to the bereaved wife and little ones.”2 While the Waterloo weekly was silent on the subject, many village residents privately suspected that a drinking problem was the root cause of the tragedy.

The regrettably too-brief life of George Washington Davies began in Portage, Wisconsin on February 22, 1868. He was the sixth and youngest child born to David Charles Davies (1833-1918) and his wife, the former Dorothy Roberts (1833-1887), both immigrants from Wales.3 George’s father was himself a distinguished rural doctor and his children grew up in comfortable circumstances. Around 1869, the Davies family relocated to the nearby town of Columbus, Wisconsin, where George spent his youth. Intelligent and athletic, George excelled in both the classroom and on the baseball diamond, primarily as a right-handed pitcher. Following graduation from Columbus High School in 1885, he enrolled in Ripon College, a small liberal arts institution near Green Bay, where he remained for a year.

Davies entered the University of Wisconsin at Madison in the fall of 1888. At the time, the University did not field an intercollegiate baseball team, having only intra-mural competition between selected nines for each class. Davies served as captain and pitcher for the freshman class team. As an impressed upperclassman later recalled, “Davies, the freshman pitcher, is a rattler, and if he had been there to pitch all the freshman games they would probably be the champions.”4 But by spring 1889, Davies had other pitching chores to attend to, namely, hurling professionally for the Milwaukee Creams of the Western Association.

Possessed of a blazing fastball and an effective overhand curve, Davies’ imposing height (about 6’4’’)5 and less-than-pinpoint control made him an unnerving sight to opposing batsman, standing only 50 feet away at the time. Reporting on an early season three-hit/seven-strikeout victory posted against Minneapolis, Sporting Life remarked that, “Davies, a law student from the University at Madison [sic], was given a trial in the box by Milwaukee and turned out to be a phenom. The Minneapolis men could do nothing with his speedy delivery.”6 Pitching for a losing (56-63) Milwaukee team, Davies went 23-11 (.676), with a 2.83 ERA in 309 innings pitched over the 1889 season. His 210 strikeouts, however, were offset by 155 walks, 16 hit-batsmen, and 17 wild pitches. Still, in the estimation of local Sporting Life correspondent William E. Smith, “Wisconsin’s pride … had cut a wide swath … [and] his work was simply remarkable.”7 At season’s end, Davies returned to his studies at the University of Wisconsin, where he again pitched for his class nine and engaged in a memorable exhibition game duel against the Western Association champion Omaha Omahogs. “Given an enthusiastic welcome” by fellow students, Davies took the box for a picked University nine and faced off against Omaha ace Kid Nichols. Striking out 14, Davies pitched superbly but dropped a 3-2 decision.8

Davies returned to the Creams for the 1890 Western Association season but pitched far less effectively in significantly reduced work. That season also saw publication of the first of several veiled references to a drinking problem that would be printed during Davies’ relatively brief professional playing career. Game accounts make frequent note of wildness, with the June 7, 1890 issue of Sporting Life declaring that “Davies’ work thus far has been very unsatisfactory.” Yet, the following week, Sporting Life correspondent Smith was hailing the work of Milwaukee hurlers Davies, Clark Griffith, and John Thornton as “especially strong,” marred only by a “want of condition on the part of Davies on one or two occasions,” often, if not invariably, sportswriter code language for being drunk.9

Davies regained top form late in the season, backing up a three-hit 5-0 shutout of St. Paul on August 19, with a one-hit 8-1 victory over Lincoln three days later. On the whole, however, Milwaukee was dissatisfied with Davies and released him several weeks before the season was over.10 The authoritative Baseball-Reference.com provides no individual statistics from the 1890 Western Association campaign, but extrapolating box scores published in Sporting Life, the writer estimates Davies’ season log as: 12-9 in 30 appearances, with a 2.00 ERA in 203 innings pitched, and 109 strikeouts countered by 89 walks, six hit batters, and 12 wild pitches.

Although listed under the “Special Student” category in the 1890 edition of the Badger yearbook, Davies apparently left the University of Wisconsin sometime during the 1890-1891 school year without graduating. For the near term, professional baseball would be Davies’ primary concern. Notwithstanding his spotty performance in 1890, both the Chicago White Stockings of the National League and the Northwestern League Spokane Bunch Grassers reportedly expressed interest in the now 23-year old right-hander.11 Davies, however, chose to remain close to home, reconciling with Milwaukee and re-signing with the team (now called the Brewers) for the 1891 season. Through mid-August, he was the best pitcher in the Western Association, going 23-7 (.767), with a 1.73 ERA in 271 innings pitched.

But if Davies’ baseball fortunes were improving, the same could not be said for the game itself. The Players League War of 1890 had left the two surviving major league circuits, the National League and the American Association, in weakened condition – a situation that would redound, ironically, to George Davies’ benefit. Bad feeling between the NL and AA in the off-season led to the latter’s withdrawal from the National Agreement, the pact which obligated one professional league to honor player contracts signed with a team in a rival circuit and to refrain from engaging an unsigned player reserved to another team. The move was ill-considered and would hasten the death of the American Association.

The case of George Davies illustrates the contract instability in baseball that followed.

On August 8, 1891, Patsy Tebeau, player-manager of the NL Cleveland Spiders, paid Davies a discreet visit. With a $500 cash advance on salary in hand, Davies signed a contract to play for Cleveland in 1892. He then returned to pitching Western Association ball, but not for long. In mid-August, the AA’s doddering Cincinnati franchise collapsed. To fill the sudden void in league ranks, the American Association invited the WA Milwaukee Brewers to assume the Cincinnati spot, which it promptly did – causing, in turn, the dissolution of the Western Association a few days later.

On August 18, 1891, the Milwaukee Brewers made a successful AA debut, beating the St. Louis Browns 7-2 behind the strong pitching of George Davies. For the next six weeks, Davies proved his major league mettle, posting a solid 7-5 record, with a 2.85 ERA in 102 innings pitched against American Association competition. For Milwaukee’s combined WA-AA 1891 campaign, Davies went a cumulative 30-12, striking out 197 batters in a yeoman 373 innings pitched. The Brewers, likewise, proved themselves major league-worthy, posting a respectable 21-15 record in their limited AA play, and the club had high hopes of retaining its big leagues status. But through no fault of Milwaukee, the American Association expired after the 1891 season. Some of its sounder operations were then absorbed into a swollen 12-team National League for the coming season. The Milwaukee Brewers were not among the chosen, being left to scramble for an 1892 berth in the newly formed Western League, a shaky minor league circuit that folded the following July.

The bitterness of William Smith, the Milwaukee correspondent for Sporting Life, was uncontainable, and found outlet in the form of censure of George Davies. According to Smith, Davies had signed a new contract with Milwaukee at the time that the Brewers were elevated to the American Association. The pact bound Davies to Milwaukee for the 1892 season, as well. This prompted Smith to label the Cleveland-bound Davies “a despicable contract jumper,” and “an ingrate with a capital I,” the last person whom Smith “thought capable of such a disreputable trick.”12 Davies responded with an unpublished letter to Sporting Life, alleging that Milwaukee had failed to make payments required under his new Brewers deal, thus voiding that contract and allowing him passage elsewhere. In time, the baseball weekly concluded that “from all that can be learned, Davies acted honorably and in good faith, and the Milwaukee club is the only factor to be blamed” for Davies’ defection to Cleveland.13 Regardless, George Davies was finished in Milwaukee and was now a member of the Cleveland Spiders. While he awaited the arrival of the 1892 season, Davies gained employment with a Dr. Stadler, in anticipation of commencing the study of medicine.14

Cleveland had been a 65-74 National League also-ran in 1891, the club more noted for the rowdy on-field behavior inspired by manager Tebeau than anything else. But the Spiders roster was not without playing talent. Outfielder Jesse Burkett and third baseman George Davis were just starting Hall of Fame careers, while shortstop Ed McKean, second baseman Cupid Childs, center fielder Jimmy McAleer, and catcher Chief Zimmer were first-rate players then in their prime. The Cleveland pitching staff was thin, with Cy Young (27-22 in 1891) and Lee Viau (18-17) the only proven winners. Still, just prior to the start of season play, veteran New York Giants star Buck Ewing warned that “Cleveland is the club to keep an eye on. In Davies, they have acquired the cream of the Western [Association] pitchers.”15

An incidental effect of the demise of the American Association was the elimination of post-season inter-league championship play. From 1884 through 1890, the National League and American Association pennant winners had met in a post-season match to determine bragging rights in baseball. To fabricate a semblance of this popular, and sometimes lucrative, clash, the now 12-team National League divided its 1892 regular season into two parts, with the winner of the first half slated to meet the second-half winner (if a different club) in a post-season best-of-nine pseudo-championship series. George Davies started off strongly with his new club, holding Chicago to only four hits in a 5-1 Cleveland victory on April 26. But soon Davies was overshadowed in the Cleveland rotation by Nig Cuppy, on his way to a superb 28-13 rookie season, and John Clarkson, the aging but still formidable veteran acquired early in the season from Boston.

By late-May, Davies was plagued by a sore arm and bad luck. Cleveland finished the first half of the 1892 season in the middle of the pack, 11½ games behind Boston. Prior to the re-start, Davies was reportedly given the obligatory 10-days notice of his release by Cleveland, but the team ultimately chose to keep him, much to the relief of local Sporting Life correspondent Elmer E. Bates, who bemoaned Davies’ ill pitching fortune. As Bates saw it, Davies “is as good a pitcher as we have. It happens every year that one of our pitchers absorbs all the hard luck. It was Davies’ turn to do this the first season. He would pitch a game in which only four or five hits were made off him and lose it, while the next day one of the other pitchers might get touched up for ten or a dozen hits, but would get away with his game all right. Davies is a No. 1 man, and the Cleveland management were wise to keep him on the pay roll.”16

Davies would see little action for Cleveland in the second-half season. As Bates explained to readers, “George Davies, although in almost perfect condition, still haunts the bench. The other pitchers are doing such good work that Tebeau thinks it is wise to let a man who pitched great ball but who had bad luck the first season, lay off until he is urgently needed. Cuppy, Clarkson and Young are all doing splendid work.”17 Behind its sterling pitching trio, Cleveland surged to the second-half crown, its 53-23 record providing a three-game margin over Boston. George Davies did not make a second-half appearance until September 17, pitching in his customary hard luck and dropping a 3-1 decision to New York. In all, Davies contributed only one victory to the Spiders second-half log, an inconsequential win over Cincinnati on September 27.

Combining both halves of the 1892 season, Davies went a lackluster 10-16 (.385) in 215 innings pitched. Yet Bates’ lament about Davies poor pitching luck seems well-grounded. While not in the same realm as the superb numbers registered by Cy Young (36-12, with a 1.93 ERA in 453 innings pitched), Davies’ 2.59 ERA was only fractionally higher than those of Cuppy (2.51) and 17-game winner Clarkson (2.55), while his hits-per-innings-pitched ratio was slightly better than that of Clarkson and comparable to Cuppy’s. Davies did not appear in the post-season series against Boston. Manager Tebeau used only Young, Clarkson, and Cuppy in the box, as Cleveland was swept five games to none, managing only a scoreless tie in the opening contest. Weeks later, it was revealed that Davies “was never in good enough shape to face the Bostons,”18 a phrase which suggests that Davies may have been drinking again.

Combining both halves of the 1892 season, Davies went a lackluster 10-16 (.385) in 215 innings pitched. Yet Bates’ lament about Davies poor pitching luck seems well-grounded. While not in the same realm as the superb numbers registered by Cy Young (36-12, with a 1.93 ERA in 453 innings pitched), Davies’ 2.59 ERA was only fractionally higher than those of Cuppy (2.51) and 17-game winner Clarkson (2.55), while his hits-per-innings-pitched ratio was slightly better than that of Clarkson and comparable to Cuppy’s. Davies did not appear in the post-season series against Boston. Manager Tebeau used only Young, Clarkson, and Cuppy in the box, as Cleveland was swept five games to none, managing only a scoreless tie in the opening contest. Weeks later, it was revealed that Davies “was never in good enough shape to face the Bostons,”18 a phrase which suggests that Davies may have been drinking again.

Davies altered his life’s course in the off-season. Following the path chosen by his father and older brother John, Davies formally embarked upon the study of medicine, enrolling in the University of Illinois College of Medicine in Chicago. For the next several years, he would devote his non-baseball energies to his studies.

But Davies still wanted to pitch, and a number of clubs, including Chicago, were interested in him, his disappointing 1892 season notwithstanding. Davies began the 1893 season with Cleveland, but his pitching career would quickly succumb to a rule change. During the previous winter, the National League had eliminated the pitcher’s box and elongated the pitching distance to 60’6” from home plate. Like many hurlers comfortable with the former set-up, Davies was critical, thinking that no more than an additional five feet was necessary to achieve the goal of increasing the game’s offense.19 The NL batting explosions of 1893, and particularly 1894, may well have proved Davies correct, but he would not be around to say “I told you so” to the game’s overseers. Hit hard in three early-1893 outings from the new pitching distance, Davies (0-2) saw no further action until consigned by Cleveland to the New York Giants on July 1. Davies fared little better with his new club. Although he managed a 1-1 record in five appearances for New York, Davies was again ineffective, giving up 41 hits and walking 13 in only 36 innings pitched.

At the end of the season, the Giants prepared to return Davies to Cleveland pursuant to some quiet understanding between the clubs, but Cleveland did not want him back.20 Davies himself wanted another opportunity to pitch in New York, and had former Spiders teammate George Davis, now also with the Giants and a budding star after a breakout 1893 season, in his corner. Sporting Life reported that “pitcher Davies will not be released by the New York club. He received his salary in full and before leaving for Chicago … he asked Treasurer [and de facto club boss Edward] Talcott to let him have another chance next year. Upon the advice of George Davis, [Giants player-manager John Montgomery] Ward will keep Davies. Davis says the ex-Clevelander can still pitch as well as anybody. Davies will not be reserved but he has promised to be on hand next March.”21

As it turned out, George Davies would not get another chance in New York. Or anywhere else. His professional baseball career was over. During his major leagues career, Davies appeared in only 46 games, going 18-24 (.429), with a 3.32 ERA spread over 369 innings pitched. He struck out 166 batters while walking 127, hitting nine batsmen, and throwing 17 wild pitches. Although the club had no further use for him, the Giants did not officially release Davies. He remained reserved to New York through the 1894 season, with George Davis again counseling manager Ward that it would be a mistake to jettison Davies without giving him a trial. If given plenty of work, Davies “can still pitch winning ball,” opined Davis.22

Meanwhile, King Kelly, managing the Allentown Buffaloes of the Eastern League, publicly expressed interest in signing Davies,23 while Charlie Cushman, Davies’ former manager in the Western Association, placed Davies’ name on the reserve list of the Milwaukee club in the latest incarnation of the Western League after the 1894 season.24 All the while, Davies continued his medical school studies in Chicago. He graduated on April 3, 1895, sending Elmer E. Bates, his Sporting Life champion, a jocular note: “I have my diploma and shall begin killing ‘em off at once, but I still read Sporting Life before I do my medical journals.”25

Following graduation, Davies moved immediately to the village of Waterloo, Wisconsin where he assumed the medical practice of his recently-deceased brother, Dr. John H. Davies. Handsome, personable, and from a highly regarded area family, George Davies thrived professionally, serving patients as both a general practitioner and a surgeon. According to the Waterloo Democrat, Dr. Davies “sleeps in the office and will attend calls at all times of the night.”26 He also immersed himself in community activities, joining various civic and fraternal organizations, while occasionally taking a turn on the mound for the village baseball team. When war with Spain threatened, Dr. Davies was among the locals immediately signing up to join a company of soldiers being organized in Waterloo,27 but he was not called to actual military duty during the brief conflict that ensued.

In February 1899, Davies returned to Chicago to marry Grace Mae Phillips, a pretty 21-year old with relatives in Waterloo. In January 1901, Grace Davies gave birth to daughter Alberta Jane. Mother and baby were “doing splendidly” reported the Waterloo Democrat, “but it is a question whether George will be able to get his face straight again, as he has been smiling continuously since the event.”28 The arrival of son Phillips Sherwood Davies in July 1902 completed the family. The only thing impairing this otherwise happy existence was a remnant from Dr. Davies’ ball playing days – the drinking problem.29

By 1905, the Davies household included widowed mother-in-law Amelia Phillips and her 82-year old mother Laura.30 That same year, Dr. Davies was further licensed in allopathy, an early form of holistic medicine. Thereafter, the historical record is silent until the fateful events of September 22, 1906 were recorded. On that Saturday afternoon, Dr. Davies retired to his office, ostensibly to catch some sleep before the professional demands of the evening arrived. At about 9:00 pm, Grace and her mother entered to bid George good-night and found him lying lifeless on a couch. A fellow doctor summoned to the scene examined the deceased and concluded “that death had taken place not more than two hours before.”31 An empty vial of the potent sleep-aid drug Bromidia was found lying nearby. A coroner’s jury concluded that George Davies had died from “an overdose of medicine taken as a sedative.”32 Given the stigma attached to suicide a century ago, local news accounts of the death did not explore any underlying causes. Dr. Davies’ drinking was no secret to locals, and many quietly believed it to be behind the tragedy.33

Following funeral services conducted by an Episcopal clergyman, George Washington Davies was laid to rest in Waterloo Cemetery. He was survived by his wife and two young children, his father Dr. D.C. Davies, his sister Julia Davies Mitchell, and brothers Lemuel and Robert Davies. Today, the grave of George Davies is marked by a large granite headstone, a silent reminder of an eventful and productive life that came to its end far too soon.

NOTES

1. As reported in the Waterloo (Wisconsin) Democrat, September 28, 1906.

2. Ibid.

3. The biographical details of this profile were derived from US Census data and various publications noted below, particularly the sketches of George Davies that appeared in the Waterloo Democrat Annual of 1897 and the Waterloo Courier, March 15, 1928. The writer is indebted to Joel Zibell, Assistant Library Director, Karl Junginger Memorial Library, Waterloo, Wisconsin for researching and providing the Waterloo archive material. George’s siblings were Julia (1859-1958), Charles (1861-1887), John (1862-1894), Lemuel (1864-1907), and Robert (1866-1908).

4. As related in Sidney Dean Thornley, Diary of a Student at the University of Wisconsin, 1886 to 1892 (Palo Alto, California: Stanford University Press, 1939), 68. The writer thanks University of Wisconsin archivist David Null for bringing this insightful look at late 19th century college life and athletics to his attention.

5. Authorities such as Baseball-Reference and Total Baseball list no height for Davies, but an 1892 Cleveland Spiders team photo shows the “tall Sycamore from Wisconsin” to be a good two inches taller than 6’2” Cy Young. Davies’ listed weight of 180 lb., presumably based upon a guesstimate printed in Sporting Life, December 18, 1890, is likely inaccurate, as the well-built Davies appears heavier than that in the Spiders team photo.

6. Sporting Life, May 25, 1889.

7. Sporting Life, October 3, 1889.

8. Played September 30, 1889, the game was recalled vividly by Sidney Thornley some fifty years later. See Thornley, 68.

9. Sporting Life, June 14, 1890. Sportswriter Smith, however, sought to forestall any fan condemnation of Davies, hastening to describe him as “an honest, reliable player … and what mistakes he does make seem to be unavoidable.”

10. As subsequently noted in Sporting Life, December 19, 1890.

11. Ibid.

12. Sporting Life, November 28, 1891. Further Smith criticism of Davies was published in Sporting Life, December 12 and 19, 1890.

13. Sporting Life, January 2, 1892.

14. As noted in Sporting Life, October 17, 1891.

15. Sporting Life, March 26, 1892.

16. Sporting Life, August 6, 1892.

17. Sporting Life, August 20, 1892.

18. Sporting Life, November 5, 1892.

19. As noted in Sporting Life, November 28, 1892.

20. See Sporting Life, September 2 and 9, 1893.

21. Sporting Life, October 2, 1893. Interestingly, the versatile George Stacey Davis had pitched in a few 1891 games for Cleveland, and he and the similarly-named George Davies are occasionally confused for one another.

22. As per Sporting Life, March 3, 1894, citing a letter from Davis to his friend and mentor John Montgomery Ward.

23. As reported in Sporting Life, March 17, 1894.

24. As per Sporting Life, October 13, 1894.

25. As revealed by Bates in Sporting Life, April 6, 1895.

26. Waterloo Democrat, September 17, 1899.

27. Waterloo Democrat, April 29, 1898.

28. Waterloo Democrat, January 18, 1901.

29. During the research of this profile, the writer’s suspicion that Dr. Davies was a drinker was confirmed by Joel Zibell of the Karl Junginger Memorial Library in Waterloo. At the turn of the last century, Mr. Zibell’s grandmother was a servant/cook in Waterloo who knew Dr. Davies and had occasion to observe him when he was under the influence.

30. As per the 1905 Wisconsin state census.

31. Waterloo Democrat, September 28, 1906.

32. Ibid.

33. Among residents of Waterloo, it was understood, if left largely unspoken, that Dr. Davies’ death was a suicide. Joel Zibell’s grandmother was among the many in the community who privately believed that Davies’ drinking was the cause behind his death, as per e-mail to the writer, October 17, 2012.

Full Name

George Washington Davies

Born

February 22, 1868 at Portage, WI (USA)

Died

September 22, 1906 at Waterloo, WI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.