Lyman Bostock

Often compared to his teammate Rod Carew, Lyman Bostock was second only to Carew as a hitter in the eyes of his Minnesota Twins manager Gene Mauch. Mauch once said he had no doubt that Bostock would eventually win batting titles. With Bostock having hit .323 and .336 during his first two full big league seasons, Mauch’s proclamation of his center fielder’s future hardly seemed bluster. In fact, from 1976-1978 only Carew and Pirates star outfielder Dave Parker hit for a higher cumulative batting average among major league every day players. Bostock’s skills were not limited to the batter’s box. He was an excellent runner and one of the finest defensive outfielders in baseball. In short, he was one of the elite multi-faceted players of the latter half of the 1970s.

Lyman Wesley Bostock, Jr. was born on November 22, 1950 in Birmingham, Alabama. The son of Annie and Lyman Sr., the younger Bostock was raised by his mother and grandmother, as his parents had separated before his birth. According to his uncle, Thomas Turner, Bostock was nicknamed “Red Bone” as a child. “We called him “Red Bone,’” said Turner. “He was a scrawny kid, and he’d get out there in the sun and he’d just turn red. He turned so red, it seemed like he was x-rayed and you could see his bones.”

Lyman Sr. was a gifted first baseman for the Birmingham Black Barons and the Chicago American Giants in the Negro Leagues. Skilled with both the glove and the bat, the elder Bostock passed his talent on to his son, through genes if not tutelage. Lyman Jr. once told New York Times reporter Dave Anderson that his father may have taught Willie Mays how to play, but he hadn’t done the same for his own son.

Beginning in 1947, many of Bostock’s relatives began to move out of Birmingham, some to the steel mills of Gary, Indiana, and others to California. In 1958, Annie moved with Lyman Jr. to Los Angeles with $7 in her pocket. She found work as a technician at a Los Angeles area hospital and spent the next 20 years employed there.

Bostock attended Manual Arts High School in Los Angeles and was an all-Southern League first baseman as a senior. He was recruited by Coach Bob Hiegert to play at Valley State College, now known as California State University-Northridge, where he earned Second Team California Collegiate Athletic Association All Star honors in 1971, finishing with a batting average of .344. He captured first team all conference honors in 1972. Despite his success at the collegiate level, Bostock, a left-handed hitter who threw right handed, was not drafted until the 26th round of the 1972 amateur draft when he was selected by the Minnesota Twins. Bostock’s explanation for the late selection: “They heard I had a bad attitude. They were wrong.”

Bostock’s hitting acumen did not diminish against professional competition. Playing for the Twins’ Pacific Coast League affiliate in Tacoma in 1974, the 6′ 1″, 175-pound Bostock made the All-Star team and finished the season with a characteristically outstanding batting average of .333. The Twins’ plan entering spring training in 1975 was to give Bostock a chance to win the center field job for the big league club. He not only won the center field job, but drew his first comparisons to Carew. He posted a .342 average during the exhibition season and headed north as the Twins center fielder and number two hitter. Bostock’s fielding was equally impressive. He had a tendency to make Willie Mays-style basket catches and explained how that came to be.

“When I was 8 years old, my mother bought me my first glove,” Bostock recalled. “But someone stole it the next day. My mother wasn’t about to buy me another one. But a friend of hers at work gave her a replacement. Unfortunately, it was a left-hander’s model and I’m right-handed. Since it was the only glove I had, I had to use it. It was the only way I could catch the ball. It became a habit, and I still have it.”

On Tuesday, April 8, opening night of the 1975 season, Ferguson Arthur Jenkins took the mound for the Texas Rangers in the midst of a Hall of Fame career. A veteran in his 13th season, in seven of which he had won at least 20 games, and coming off one of the most successful seasons of his career, he faced an equally credentialed opponent in Minnesota Twin Rod Carew as the game began in front of 28,787 fans at Arlington Stadium in Texas. Carew singled to right to start the game. Bostock then stepped into the batter’s box for the first time as a major league player and, facing Jenkins, who had won 174 games as a major league pitcher, calmly drew a base on balls in that debut plate appearance. The Twins would send all nine batters to the plate in that first inning, and score three runs off Jenkins.

Carew again led off the following inning, this time flying out to right. Bostock started another rally with his first major league hit in his first major league at-bat, a single to right field. Jenkins, in an uncharacteristically short performance, would not last through the second inning. Bostock would go on to face Jenkins 33 times in his career, reaching base safely 14 times on eight singles, four doubles, and two walks, for a batting average of .387 and an on base percentage of .424. In his debut game, Bostock reached base three times in six plate appearances and scored all three times.

He finished his rookie season with 369 at bats, posting an average of .282, and an on-base percentage of .332. He missed substantial time after sustaining an ankle injury that required surgery for bone chips, occasioned after a diving catch of a Bert Campaneris fly ball, and subsequent crash into the outfield wall in a game against the Oakland Athletics. This injury was the second of the young season, and exemplified Bostock’s feverish style of play. He had fractured a finger in spring training, causing him to miss most of the latter half of March. He hit .391 during a month in the minors following ankle surgery. Bostock would later miss more time during the 1975 season due to a thumb injury.

After the season ended, Bostock played in the Venezuelan Winter League for Aragua, where once again he found himself among the league leaders with a .353 batting average until he re-injured his ankle, resulting in a premature end to his winter season.

In 1976, in spite of some nagging injuries including a pulled hamstring, Bostock hit .323 with an on-base average of .364 and an OPS of .794. His batting average was fourth best in the American League behind George Brett, Hal McRae, and Bostock’s Hall of Fame teammate, Rod Carew. Bostock also scored 75 runs, drove in 60, and stole 12 bases. He struck out only 37 times in 474 at bats. Midway through the season, journalist Bob Fowler surmised that it appeared “the Twins will have an excellent center fielder for the next decade.” That sentiment voiced the opinion of many in baseball and in the media. Perhaps Bostock was, as he claimed to be, “born to play baseball.”

Bostock played in the Mexican Winter League after the 1976 season. He led his team to the championship, stroking two key home runs in the championship series, in a victory over the team managed by Twins legend Tony Oliva.

Bostock’s breakout season came in 1977. “Rapidly emerging as one of the best hitters around,” was a phrase used to describe Bostock during the campaign. He finished in the American League’s top seven in as many major offensive categories, including second in average (.336), fourth in runs scored (104), and seventh in on base percentage (.389). His OPS was an outstanding .897.

During the season, he tied a major league record for putouts in a nine inning game by a center fielder, with 12, and set an American League record for putouts in a doubleheader, with 17. He helped the Twins set a franchise record for most runs scored in a season. He had become a star, and was the most sought-after player in the free agent market between the 1977 and 1978 seasons.

The new free agency system in major league baseball was turning players into millionaires overnight. After the 1976 season, Reggie Jackson had signed with the Yankees. Now, after the 1977 season, reports suggested that Jackson was helping New York court Bostock into the Yankee fold. Other reports surfaced that the Mets were willing to trade ace pitcher Jerry Koosman in exchange for Bostock, and a chance to sign him for the 1978 season. By the close of the 1977 season, Koosman had won 137 games in 10 seasons for the Mets, and posted ERAs under 3.00 four times, while crossing over 4.00 only once.

When the free agent draft (a process since abandoned) took place, Bostock was chosen by the maximum number of clubs, 13, and was selected in the first round by eight different teams. Twins owner Calvin Griffith claimed that financial considerations prevented the Twins from re-signing Bostock during the season.

Although Minnesota ultimately offered Bostock a sum of money that he found adequate, the manner in which they handled the negotiations had upset Bostock. “That was way more than enough money,” he said, referring to the six-year, $2 million contract the Twins eventually offered.

“If they had offered me that at the beginning of the season, I’d have signed. But by the end I just didn’t want to stay there. I’d be defeating the purpose of what Curt Flood has done for the players. He wanted everybody to be able to enjoy the beauty and the freedom of the game.” Bostock’s disdain for the penny-pinching Griffith was clear. “If it wasn’t for the owner, Minnesota would be a great place to play.”

The collaborative efforts of Reggie Jackson and Yankee owner George Steinbrenner to put Bostock in pinstripes were in vain. Although the Yankees reportedly offered Bostock a quarter of a million dollars more, and San Diego Padres owner Ray Kroc offered him McDonald’s franchises in addition to a hefty contract, Bostock signed a deal with the California Angels that would reportedly pay him $2.3 million over five years, an astounding contract at the time. He had been paid $20,000 by the Twins in 1977.

Gene Mauch, Bostock’s Minnesota manager, called Bostock the second-best hitter in all of baseball behind Rod Carew. Bostock’s departure, along with that of slugging outfielder Larry Hisle in the same free agent class, led to Mauch’s attempt to leave the Twins. So disturbed by the loss of two of his best and most promising players, Mauch badly wanted to go elsewhere, and in 1981, did, in fact become the Angels’ manager.

The 1978 season started poorly for Bostock. So poorly, in fact, that he believed he did not deserve the lucrative contract he had just signed, and demanded that Angels owner Gene Autry keep his money until Bostock started earning it. When Autry refused, Bostock gave the money to charity, reportedly a $50,000 sum.

It was not the first time Bostock had involved himself in charitable pursuits. He had previously helped fund the rebuilding of his mother’s church and purchased sporting equipment for underprivileged youth in Los Angeles. Bostock finished April hitting .147 and by the end of May was only at .209. He would later say that near the end of his slump, he “was almost hallucinating, seeing myself step out of my body at the plate. It’s the way some people think they see Martians.” In June, his bat came alive, and his average for the remainder of the season was well over .300. His final average was .296, with an on-base percentage of .364. That capped a three-year stretch during which Bostock posted the third-highest average in the game, behind only Rod Carew and Dave Parker, and ahead of the elite hitters of the era, including names like Brett, Pete Rose and Bill Madlock, who combined for 10 batting titles in their careers. Bostock garnered slight but well-deserved MVP consideration in both 1977 and 1978. His body of work for that three-year stretch is impressive in and of itself, but consider that those were his first three full major league seasons, and the numbers could have become even more impressive. Hall of Fame pitcher and Angels teammate Nolan Ryan called him “one of the few natural hitters” in the American League.

On September 23, 1978, in the waning days of his fourth big league season, Bostock was riding in the back seat of his uncle’s car through the streets of Gary, Indiana. Bostock had doubled in a losing cause against the White Sox in Chicago earlier that day, as the Angels fell to the Sox, 5-4. Bostock made the final out of the game, then traveled to nearby Gary to visit his uncle Ed Turner. Bostock and his uncle were with two ladies who were long-time family friends, Joan Hawkins and Barbara Smith, the estranged wife of a man named Leonard Smith.

At approximately 10:40 p.m., Leonard Smith drove up to the Bostock car and began to argue with the occupants. Turner tried to drive away from Leonard Smith, but Smith pulled his car alongside the Bostock vehicle at the intersection of Jackson and 5th Street, at a traffic light that had turned red.

There, Smith, evidently in an unwarranted jealous rage, fired a shotgun into the backseat of the car, his buckshot pellets striking Bostock in the right side of the head. Bostock was taken to St. Mary’s Medical Center where doctors worked on him in an effort to save his life for almost three hours. He died at 1:30 a.m. the following morning.

The Angels got the word at their hotel, with teammate Don Baylor learning of the shooting from his wife phoning from California, others from Angels general manager Buzzie Bavasi, who told Baylor and his teammates not to go to the hospital, as there was no hope. It fell to Baylor to pass the word to the team, and hardened ballplayers broke down in tears. Baylor and teammate Joe Rudi sat in the hotel hallway for hours, talking, tearful, unable to sleep, knowing they had to face a ballgame that afternoon.

Manager Jim Fregosi returned to the Angels’ hotel around midnight to find players Kenny Landreaux and Danny Goodwin “standing in front of the lobby. I was about to say that it was a bit late to be going out when I noticed they were both in tears.”1

The following day, when the Angels reported to Comiskey Park to play the final game of their series with the White Sox, they found a swarm of media and Bostock’s locker already empty, his kit in a duffel bag. Angels Designated Hitter Don Baylor, writing about the day in his autobiography Don Baylor, described chasing a photographer away from the empty locker. Fregosi, looking prematurely aged, canceled batting practice, and Max Patkin, the “Clown Prince of Baseball,” scheduled to perform before the game, canceled his act out of respect for Bostock.

Fregosi told reporters, “We’re professionals and this is our business. We’ll play this game like it should be played. Right now, the team has to be secondary. A man has lost his life. A good friend is gone. Lyman Bostock had a super feeling for the game. He was close to everyone. I’ll hold a meeting, but there’s not much I can say. Everyone knows what kind of guy he was.”2

“I ran sprints with (Joe) Rudi and (Bobby) Grich. My head was still pounding. I didn’t want to play and needed to play at the same time,” Baylor wrote.3 “In my first at-bat I hit the ball off the upper deck in left field, my 33rd home run of the season. The Angels equipment manager, Mickey Shishido, took me aside and said, ‘That was for Lyman, you did that for Lyman.’ Mickey did not have to tell me. I knew. But it didn’t seem enough.”

The Angels trounced the White Sox, 7-3, behind Baylor’s home run and Nolan Ryan’s six strikeouts in seven innings. Kenny Landreaux played right field. After the game, the Angels flew home, and had an off-day. Baylor went to the airport to meet Bostock’s wife Yuovene, when she flew in with Bostock’s coffin.

Funeral services were held on September 28, 1978 at Vermont Square United Methodist Church in Los Angeles. Bostock’s popularity was evident in the days following his tragic death. Bobby Grich, an Angel teammate, spoke of Bostock’s outgoing personality. “There were never enough hours in the day for Lyman,” said Grich. “We called him ‘Gibber-Jabber’ because he was always talking. Everyone was crazy about him because he was so outgoing and friendly, always up, always looking on the bright side.”

Angel pitcher Ken Brett spoke at the funeral, telling mourners: “He enlivened our clubhouse and took us out of the darkness of defeat. But he was a winner. He enjoyed life so much because he had so little at the beginning.”

Bostock was buried at Inglewood Cemetery in Los Angeles. The Angels regrouped and won five of their last seven games, staving off mathematical elimination in the American League West until the season’s last series.

To add to the pain, within hours of the shooting, Bostock’s agent, Abdul Jalil, phoned the Angels, demanding part of Bostock’s salary for an unfinished business deal of which the outfielder’s family was unaware. The Angels had already paid Jalil $145,000 to cover his agent’s fee. Bavasi vowed never to deal with Jalil again, and soon traded Jalil’s other three clients on the team: Ron Jackson, Landreaux, and Goodwin.

Bostock’s $2.2 million contract was covered by Lloyd’s of London, but Yuovene Bostock was hit with a significant tax penalty, because Jalil had rejected the Angels’ original recommendation that Bostock take out an insurance policy instead of the team. Had Bostock done so, the benefits would have gone to Yuovene free of tax. Jalil’s decision saved Bostock $10,000 in insurance fees but cost Yuovene about $500,000.

Police reported that Smith, a 31-year-old unemployed steelworker, perpetually followed his wife, and had threatened her earlier that day. He was arrested in his apartment about seven hours after the shooting, and charged with first-degree murder. Smith’s attorney, Nick Thiros, argued that his client was temporarily insane when he committed the crime. In July of 1979, a Lake County, Indiana jury deciding the case declared itself deadlocked, and the presiding judge, James Kimbrough, declared a mistrial.

The case was tried again in November, and this time Thiros convinced a jury to acquit Smith, finding him innocent by reason of insanity. Smith was ordered to undergo psychiatric care in the Indiana state mental hospital in Logansport. He spent less than one year in the hospital. Having been found no longer in need of psychiatric care or commitment, Smith was released in the summer of 1980, during what would have been Bostock’s sixth major league season. Jack Crawford, the Lake County prosecutor, called the case “a legal tragedy” and declared that Smith was “a dangerous person inclined to violence.” The verdict and release pushed Indiana to change its laws to allow those found mentally impaired to also be found guilty and imprisoned.

Nevertheless, less than two years after ending Lyman Bostock Jr.’s career and life, Smith was a free man.

Notes

1 Rob Newhan, The Anaheim Angels, A Complete History, Hyperion, 2000, p. 180.

2 Ibid., p. 181.

3 Don Baylor and Claire Smith, Don Baylor, St. Martin’s Press, 1989, p. 118.

Sources

www.baseball-reference.com

www.retrosheet.com

www.baseball-stats-online.com

Bob Fowler, “Bostock Bat Brings out Grins on Twins,” The Sporting News, 4/5/75, p. 40.

Bob Fowler, “Twins Found Foursome with Future,” The Sporting News, 10/25/75, p. 18.

Bob Fowler, “Twin Bostock Aims for Five-Star Rank,” The Sporting News, 7/3/76, p. 13.

1976 Twins Media Guide

Bob Fowler, “All Fans Alike Oliva Learns They Want Winner,” The Sporting News, 2/26/77, p. 46.

Ken Nigro, “White Sox, Twins Could Be Big Losers of Free Agents,” The Sporting News, , 5/21/77, p. 8, by

Jack Lang, “Doc Seen as Partial Cure for Mets,” The Sporting News, , 10/15/77, p. 16.

Joseph Durso, “44 Players are Drafted – Yankees and Mets Have 13 in Common,” New York Times, 11/5/77, p. 33.

Bob Fowler, “Twins in Deeper Trouble as Mauch Wants Out,” The Sporting News, , 11/19/77, p. 50.

Bob Fowler, “Autry Keeps on Shooting Down Angels’ Targets,” The Sporting News, , 11/19/77, p. 48.

Dick Young, “Jackson in Selling Job,” The Sporting News, , 12/3/77, p. 18.

Dick Miller, “Bostock Ranks Angels’ Halo Ahead of Big Bucks,” The Sporting News, , 12/10/77, p. 47.

Dave Anderson, “Why Bostock Spurned Mets, Yanks,” New York Times, 3/7/78, p. 28.

“The Give-Away Pay Plan,” New York Times, 5/1/78, p. C4.

“Angel Star Bostock Dies in Shooting,” Washington Post, 9/25/78, p. D1.

“Baseball Star Slain; man held,” Bill Grady, Chicago Tribune, 9/25/78, p. 1.

“Man Held in Slaying of Bostock,” John O’Brien, Chicago Tribune, 9/26/78, p.2.

Gary Libman, “Ex-Mates Mourn “Mr. Logic’s’ Death,” Chicago Tribune, 9/26/78, p. C3.

Thomas Boswell, “Praise Pours In — Too Late for Bostock,” Washington Post, 9/26/78, p. E1.

“Bostock Eulogized as “Winner’ by Teammate Brett at Funeral,” Washington Post, 9/29/78, p. E2.

“Jury Deadlocks, mistrial ruled in Bostock slaying,” Chicago Tribune, 7/14/79, p. B3.

“Commitment Hearing is Set: Insanity Verdict in Bostock Case,” Chicago Tribune, 11/17/79, p. 53.

“Man freed in Bostock death to receive psychiatric care,” Chicago Tribune, 12/20/79, p. 14.

“Bostock Slaying Defendant is Slated to Gain Freedom,” New York Times, 6/7/80, p. 14.

“Called a “legal tragedy,’ Bostock killer gains freedom,” Chicago Tribune, 6/21/80, p. S5.

Patrick Reusse, “Ten years Later the Question Lingers: Why?” Minneapolis-St. Paul Star Tribune, 9/25/88, p01CC.

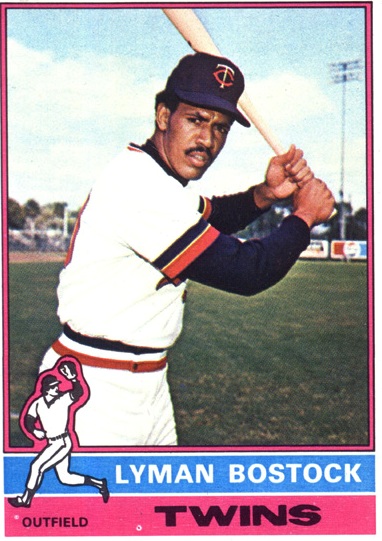

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Lyman Wesley Bostock

Born

November 22, 1950 at Birmingham, AL (USA)

Died

September 24, 1978 at Gary, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.