Billy George

Late-1880s pitcher Billy George was a flame-throwing but incurably wild left-hander, an early prototype of the Steve Dalkowski model.1 In his rookie season with the 1887 New York Giants, George established an ignominious major-league pitching record that stands to this day – most walks issued by a pitcher in a single game: 16.2 Years later, his hometown newspaper lamented, “(I)f he had possessed control he would have undoubtedly been one of the greatest pitchers of the age. His inability to locate the plate, however, forced him to give up pitching and go to the outfield.”3 When he failed a brief trial in the pasture, George was released to the minors, where he rather quickly developed into a formidable righty batter, twice posting batting averages over .400. Sadly, he was never given a chance to test his batting skills against major-league pitching, spending a decade waiting for the call-up that never came. Retiring from the game after 1899, he spent the final years of his too-brief life as the proprietor of a popular neighborhood watering hole.

Late-1880s pitcher Billy George was a flame-throwing but incurably wild left-hander, an early prototype of the Steve Dalkowski model.1 In his rookie season with the 1887 New York Giants, George established an ignominious major-league pitching record that stands to this day – most walks issued by a pitcher in a single game: 16.2 Years later, his hometown newspaper lamented, “(I)f he had possessed control he would have undoubtedly been one of the greatest pitchers of the age. His inability to locate the plate, however, forced him to give up pitching and go to the outfield.”3 When he failed a brief trial in the pasture, George was released to the minors, where he rather quickly developed into a formidable righty batter, twice posting batting averages over .400. Sadly, he was never given a chance to test his batting skills against major-league pitching, spending a decade waiting for the call-up that never came. Retiring from the game after 1899, he spent the final years of his too-brief life as the proprietor of a popular neighborhood watering hole.

William George4 was born on January 27, 1865, in Bellaire, Ohio, then a rapidly expanding village located directly across the Ohio River from Wheeling, West Virginia. He was the third of four children born to New York native Henry George and his German immigrant wife Veronica (nee Hammell).5 Apart from their Roman Catholic faith, little is known about the family. But by the time of the 1880 US Census, father Henry was no longer a member of the household and presumably deceased, while his three sons, including 15-year-old Billy, were listed as laborers. Thereafter, Billy found work as a glass-blower in a Bellaire glass plant.6

In Billy George’s day, the greater Wheeling area was a baseball hotbed, producing Jesse Burkett, Jack Glasscock, Sol White, and other accomplished professional players. George’s career path took the customary route, beginning with sandlot play as a boy before graduating to faster competition as a teenager. He first gathered press notice as a crack left-handed shortstop-third basemen for the Globes, an amateur nine sponsored by the pool hall where our subject evidently misspent a good deal of his youth; Billy would later become a locally renowned pool shark.7 In 1886 he was one of several Globes players enlisted by the Maple Leafs of faraway Guelph, Ontario, reputedly the best semipro club in Canada.8 By this time, Billy wanted to try pitching, but saw action in the box during only eight of the Maple Leafs’ 62 games.9 Nevertheless, that was sufficient for the New York Giants to sign him for the 1887 season.10 At age 22, the inexperienced George would be making the jump from semipro ranks to the National League.

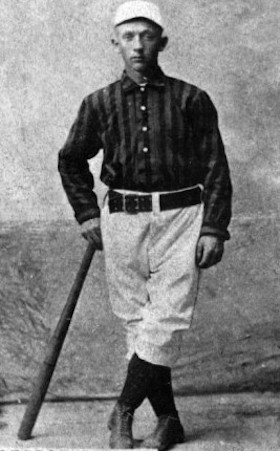

Slightly built (5-feet-8, 150 pounds) with blond hair and a clean-shaven baby face, the Giants’ new pitching recruit was not an intimidating figure in the box. But the fact that he threw very hard with little control unsettled many opposing batsmen. After an unimpressive preseason outing against the Columbia College varsity, Billy George made his major-league debut on May 11, 1887, against Washington. He pitched well in the early innings, but tired thereafter and barely survived a four-run Washington ninth to notch a 9-8 victory. In addition to nine hits, George walked six, hit a batter, and threw three wild pitches. Still, his reviews were favorable, with the New York Tribune acknowledging his “fairly good work,”11 while the New York Herald adjudged that George had “pitched his first championship game in good shape.”12

In his next two starts, George staggered to ugly, high-scoring wins. Then his fortunes reversed. He lost nine straight decisions, with the lowlight being the 16-walk debacle against Detroit on May 27. But rather than release the ineffective youngster, New York brass shuttled George (and fellow rookie hurler John Roach) to the club’s reserve squad, where he gained pitching experience against lesser competition and began to show improvement.13 Given a postseason exhibition game start against Washington, George demonstrated just how far he had come, allowing only four hits, three walks, and no earned runs while striking out 11, in a 5-4 complete-game triumph.14 That outing earned the young lefty a ticket to the Giants’ 1888 spring camp, despite a dismal regular season pitching line. In 13 games, he had gone 3-9, with an unsightly 5.25 ERA/1.991 WHIP (walks plus hits per inning pitched) in 108 innings.

The 1888 New York Giants were a powerhouse that featured no fewer than six future Hall of Famers: Buck Ewing, Roger Connor, Tim Keefe, Mickey Welch, John Montgomery Ward, and Orator Jim O’Rourke. And George jeopardized his chances of gaining a place on the packed Giants roster by remaining in Bellaire nursing an illness for almost the entire preseason. Perhaps surprisingly, he made the club anyway, but saw little game action as the Giants cruised to their first National League pennant. But George pitched well when given the rare chance. On October 2 he concluded the Giants’ sterling 84-47 season with his finest major-league performance, a 6-2 complete-game win over Detroit in which he allowed but six hits and one walk while fanning nine. In limited action overall, Billy had gone 2-1, with an impressive 1.34 ERA/0.861 WHIP in four games pitched. He then found a comfortable viewing spot as the Giants squared off against the American Association’s pennant-winning St. Louis Browns in a postseason best-of-10-games world championship match.

The Giants had clinched the laurels by the conclusion of Game Eight, rendering the final two games meaningless. But the two clubs played on, allowing Billy George a taste of championship-game action. Regrettably, when given the Game Nine starting assignment, he proved unable to show his regular-season form, absorbing a 14-11 battering in 10 innings. The following day, however, George gained a measure of personal satisfaction as the Giants’ first baseman, going 2-for-4 with a double, home run, and four RBIs in another pointless slugfest won by the Browns, 18-7.

This strong final-day plate work may have accelerated plans for a position change by George. Ambidextrous, he had begun throwing righty in late-season practice sessions, perhaps in hopes of improving his prospects to become an everyday player in future.15 But the 1889 season replicated his previous one. George made the Opening Day Giants’ roster, but by mid-May he had appeared in only one New York game – as a left-handed outfielder. He made his farewell appearance in a Giants uniform on May 30, playing the outfield in both games of a doubleheader against Indianapolis and going a combined 4-for-8 at the plate. Billy was then loaned to the Springfield (Illinois) Senators of the Central Inter-State League, batting an eye-catching .330 in 26 games. To no avail. In late June, New York dropped him.

Because his release had been unconditional, George was free to sign anywhere and soon joined the Columbus Solons of the American Association, managed by his former Guelph teammate Al Buckenberger.16 Inserted as an emergency relief pitcher for Columbus on July 3, he was less than a success in his debut, as he was hit hard by Kansas City. Thereafter, throwing-arm miseries necessitated a trip to the famous spa in Mt. Clemons, Michigan, a sabbatical that did not sit well with the Columbus press corps.17 George returned to Columbus in time to play four late-season games in the outfield, botching two of his six fielding chances. In 17 at-bats, he garnered four base hits (.235) and three RBIs. Billy and the Solons then parted ways.

George soon found new employment, signing with the Indianapolis Hoosiers, a National League club piloted by Wheeling buddy Jack Glasscock. With the upstart Players League taking the field for the 1890 season, there would now be 24 major-league teams in need of bodies. But when the National League liquidated the weakling Indianapolis and Washington franchises as a preemptive strike in the looming interleague war, George became an incidental casualty. Unlike Glasscock, Amos Rusie, Jerry Denny, and other Indianapolis stalwarts shipped to the decimated NL New York Giants, there were no takers for George. Unbeknownst to the 25-year-old, his major-league playing days were over.

Although a NL-AA ballplayer for almost three entire seasons, Billy had appeared in a mere 30 games, total. As a pitcher, his log closed at 5-10 (.333), with a 4.51 ERA/1.724 WHIP in 149⅔ innings pitched. He had struck out 78, but walked 103, hit 15 batters, and thrown 26 wild pitches – his lack of control yielding the equivalent of nearly one pitching mishap per inning. Although not given much of an opportunity, his plate work was similarly unimpressive: a .210 BA with only two extra-base hits in 124 at-bats. Meanwhile, his fielding, as both a pitcher (.860 fielding average) and an outfielder (.833), had been lousy.

Still young and unaware of the career minor leaguer-fate in store for him, George regrouped. Staying close to home, he joined the Wheeling Nailers of the Tri-State League for the 1890 campaign. And when second baseman-manager Bob Glenalvin left the club to join the NL Chicago White Stockings in early July, George assumed the post of Wheeling field leader as well.18 He did a creditable job as manager, guiding the Nailers to a (41-34) third-place finish, and a better one as a player. Confining himself to the outfield, he improved his fielding (.933), although his once-powerful left arm had weakened considerably. Conversely, his work with the stick had grown potent. Billy posted a .352 batting average,19 beginning a decade of sustained minor-league batting excellence.

For the 1891 season, George signed with the Portland Gladiators of the independent Pacific Northwestern League. He hated the rainy Portland weather enough to quit the club in early July and was suspended by minor-league baseball’s governing board.20 Reinstated upon his return to Portland a month later, George had batted a robust .337, with 57 extra-base hits, in 96 games by season’s end. The following spring he rejoined Portland and was batting .291 when the club collapsed in early August. Days later, the rest of the PNW League abandoned play. George and various teammates then finished the season with Helena in the Montana State League.21

Over the winter, reports surfaced that the Cincinnati Reds were interested in George. Nothing came of it, but Billy leveraged the situation to extract the Southern League maximum $150-a-month salary when he signed with the Montgomery Colts.22 As it had previously, offseason enthusiasm for endeavors of chance left him in need of funds; Billy did well enough hustling pool, but fared poorly with wagers on the ponies and cockfighting. And by now, he had acquired familial responsibilities: a wife named Mary, and infant daughter Flora. Two more baby girls would follow before the decade was out.23 For the short term, Billy bounced between Montgomery and the Savannah Electrics, (with perhaps a brief turn for the Mobile Blackbirds, too24) before the financially-shaky circuit stopped play in mid-August. At the time, Billy was batting a combined .311 in 78 games. He then went home to Bellaire.

The following year, George attempted to play off two Western League clubs against each other, trying to increase the take for his services. First, he accepted $60 advance money from the Detroit Wolverines. But Detroit neglected to include George’s name on the player list submitted to league President Ban Johnson. George then signed with a WL rival, the Grand Rapids Rippers. Over bitter Detroit protest, Johnson determined that Grand Rapids was entitled to George.25 But when Billy disregarded a Johnson directive to return the advance money to Detroit, he was suspended.26 Restored to the ranks after he paid up, George completed an extraordinary offensive season. In 115 games, he had batted a WL second-best .423, with 70 extra-base hits, 137 runs scored, and 32 stolen bases. Yet, no major-league interest in George was reported during the offseason.

Returning to Grand Rapids to begin the 1895 season, George encored with a second consecutive exceptional batting performance. Traded by the fiscally troubled Grand Rapids club to league competitor St. Paul at midseason, he finished the campaign with a .403 batting average. His WL-leading 241 base hits27 included 89 extra-base knocks. Billy also posted a .620 slugging percentage, scored 169 runs, and stole 38 bases. But again, George strangely attracted no reported interest from major-league clubs. Obliged to return to St. Paul, Billy posted a third straight boffo season, batting .383.28 But still nothing from the majors. Finally, after George had posted yet another gaudy sets of stats for St. Paul in 1897 (.338 BA, a WL-leading 208 base hits, 142 runs scored, 49 SB), the St. Louis Browns took notice, offering outfielder Dan Lally in exchange for George.29 St. Paul accepted, but George’s hopes for a return to the bigs were dashed when St. Louis rescinded the deal several months later.30

Billy George was no longer wanted in St. Paul either, and his professional career began the slide toward its finish. In 1898 he played in the slower Atlantic League, splitting the season between Norfolk and Newark. A salary dispute with management ended his stay in Newark, but in July 1899 it was reported that George had signed with the Wheeling Stogies of the Interstate League.31 But it appears that he saw little or no action with the team.32 His ballplaying days were now over. Although his major-league career had been brief and inconsequential, George had been an outstanding hitter in his 10-year tour of the minors. Using incomplete Baseball-Reference statistics yields a .358 lifetime minor-league batting average. (That would probably be even higher if statistically lost seasons could be figured in.) He had also been an outstanding baserunner, and a passable outfielder.

Once he retired from the game, Billy George led an unremarkable life. He lived with his family in a modest home next door to his aging mother in Bellaire, and operated a billiards parlor. By 1909 he was the proprietor of George’s Café, a popular neighborhood saloon.33 As later recounted in his obituary, “Mr. George’s friends included men of all walks of life. He was one of the most popular men in this city.”34 In early August 1916, he underwent surgery for a ruptured gall bladder. The operation appeared a success, and George was discharged from the hospital several days later.35 But complications soon set in. Rushed back to Wheeling North Hospital, William “Billy” George died there on the morning of August 23, 1916. He was 51. The cause of death was subsequently determined to be peritonitis.36 Following a Funeral Mass at St. John’s Church, his remains were interred at Mt. Calvary Cemetery, Bellaire. Survivors included his wife, Mary, and daughters Flora and Marcelline.

Sources

Sources for the biographical detail contained herein include material from the Billy George player file maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; George family-tree info posted on Ancestry.com; US census data and listings in the greater Wheeling, West Virginia, City Directory, and certain of the newspaper articles cited below, particularly the William George obituary published in the Bellaire (Ohio) Daily Leader, August 23, 1916. Unless otherwise noted, statistics have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 Left-hander Steve Dalkowski was a near-legendary 1960s minor leaguer noted for both extraordinary velocity and atrocious control.

2 Remarkably, less than two months later, the 16-walks-issued mark was tied by Chicago left-hander George Van Haltren (later a near Hall of Fame-caliber outfielder) in a 9-4 Chicago victory over New York. His opposite number that July 16, 1887, afternoon was none other than Billy George himself. Years later, right-hander Bruno Haas of the hapless 1916 Philadelphia A’s equaled the single-game 16-walks record set by George and Van Haltren.

3 Bellaire (Ohio) Daily Leader, August 23, 1916.

4 Modern baseball reference works list our subject as William M. George, perpetuating a nonexistent middle initial first introduced in 1951 by the original edition of the Turkin & Thompson Official Encyclopedia of Baseball. As with many entries in Turkin & Thompson, the provenance of this “M.” is untraceable. And it is contradicted by a slew of government documents published during George’s lifetime that indicate that he had no middle name or initial. The modern identification of him as Bill George is also anomalous. To family, friends, and the baseball world of his time, our subject was known as Billy George, and that is what he is called here.

5 His siblings were Robert (born 1861), John (1863), and Mary (1869). The writer is indebted to reference librarian Stacy Anderson and genealogist Julie A. Kloss of the Belmont County (Ohio) District Library for their help in tracing our subject’s family history.

6 As per Major League Baseball Profiles, Volume 2: The Hall of Famers and Memorable Personalities Who Shaped the Game, David Nemec, ed. (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 487.

7 The Wheeling Register, January 18, 1892, later reported on a much ballyhooed match between “Billy George, the ball player and champion pool player of Bellaire,” and another local hustler named Clearwater. When ball number 150 disappeared into a corner pocket, George’s wallet became $100 lighter.

8 As per the Wheeling Register, February 10, 1886, and an undated circa 1888 New York Clipper article contained in the George file at the Giamatti Research Center.

9 According to The Sporting News, February 9, 1887.

10 According to the Wheeling Register, October 21, 1886, George was signed by Walter Appleton, a junior partner of the Metropolitan Exhibition Company, the Giants’ corporate alter ego.

11 New York Tribune, May 12, 1887.

12 New York Herald, May 12, 1887.

13 As noted in Sporting Life, July 6 and 13, 1887.

14 As reported in Sporting Life, October 23, 1887.

15 As noted by Sporting Life, September 19, 1888.

16 As reported in the Wheeling Register, July 1, 1889, the Kansas City Times, July 3, 1889, and elsewhere.

17 As per Nemec, 488.

18 As reported in the Wheeling Register, July 11, 1890, and Sporting Life, July 19, 1890.

19 Baseball-Reference provides no stats for the 1890 Wheeling club. Billy George’s individual batting and fielding averages for Wheeling were published in Sporting Life, April 4, 1891.

20 As reported in Sporting Life, July 4 and 11, 1891.

21 As per Sporting Life, September 24, 1892.

22 See Sporting Life, February 18, March 25, and April 1, 1893, for the specifics.

23 Time and haphazard recordkeeping have somewhat shrouded Billy George’s domestic situation. In all probability, his wife was Mary Lappert (or Lepperd), a local woman some seven years his junior. And recently posted George family-tree info confirms that Mary George gave birth to a daughter named Marcelline in 1897. But the situation is muddled by West Virginia marriage records which indicate that William George and Mary Lepperd were not married until January 17, 1911. Whatever their legitimacy, daughters Flora and Marcelline lived into their 80s, but nothing is known of the third George daughter except that she died on or about July 29, 1898, as reported in Sporting Life, August 6, 1898. Sadly, no trace of this daughter, including her obituary, could be found in local reportage. In addition, the existence of a fourth George child, name/gender/birth date unknown and perhaps also prematurely deceased, is inferred by a 1930 US Census entry which identifies Mary George as the mother of four children, two living.

24 Baseball-Reference places George with three Southern League clubs during the 1893 season, but the writer found no mention of his Mobile tenure in Southern League reportage.

25 See Sporting Life, February 24, 1894.

26 As per Sporting Life, July 28 and August 11, 1894. Grand Rapids teammate Fred Carroll, who had similarly disregarded a Johnson directive to return $100 advance money accepted from Detroit, was also suspended.

27 As per The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds. (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 2nd ed. 1997), 120. Baseball-Reference credits George with only 240 hits, making Perry Werden of Minneapolis, who also registered 241 base hits that season, the WL hits leader by B-R lights.

28 Baseball-Reference provides no statistics for George in 1896. His batting average for 1896, however, was published in Sporting Life, April 4, 1897. St. Paul teammate Jack Glasscock led the club with a .431 BA.

29 As reported in Sporting Life, October 23, 1897.

30 As per Sporting Life, February 19, 1898.

31 As reported in Sporting Life, 1899.

32 Baseball-Reference includes the 1899 Wheeling Stogies on its itinerary of clubs that George played for, but provides no stats. Tellingly, the Wheeling Register, which followed closely the fortunes of both its hometown club and local players like Billy George, makes no mention of George being a member of the 1899 Wheeling team.

33 The 1909 greater Wheeling City Directory contains an advertisement for “George’s Café: Billy George, proprietor. Stocked with choice wines, liquors, cigars, and local and foreign beers.”

34 Bellaire Daily Leader, August 23, 1916.

35 Ibid.

36 As per the death certificate for William George, dated August 24, 1916. The George death certificate is viewable online via SABR member Frank Russo’s TheDeadballEra website.

Full Name

William George

Born

January 27, 1865 at Bellaire, OH (USA)

Died

August 23, 1916 at Wheeling, WV (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.