Gene Dale

Of the players officially expelled from Organized Baseball in the early 1920s, Gene Dale was among the least notorious. A lanky right-handed pitcher, Dale had won 18 games for the Cincinnati Reds in 1915 but was no longer a major leaguer at the time of his banishment. Rather, his disgrace emanated from suspected involvement in the rigging of the 1919 Pacific Coast League pennant race, a matter which came to public light several weeks before the eruption of the Black Sox Scandal.

Of the players officially expelled from Organized Baseball in the early 1920s, Gene Dale was among the least notorious. A lanky right-handed pitcher, Dale had won 18 games for the Cincinnati Reds in 1915 but was no longer a major leaguer at the time of his banishment. Rather, his disgrace emanated from suspected involvement in the rigging of the 1919 Pacific Coast League pennant race, a matter which came to public light several weeks before the eruption of the Black Sox Scandal.

An attempt to prosecute the PCL fix participants in the courts was unsuccessful, but league officials responded to dismissal of the criminal case with punitive action of their own, precipitating the near-immediate expulsion of Dale and three other ex-major leaguers from the game. Among other things, this provided an instructive precedent for Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis in dealing with the soon-to-be-acquitted Black Sox. Meanwhile, Gene Dale withdrew into the obscurity which shrouded the remainder of his life.

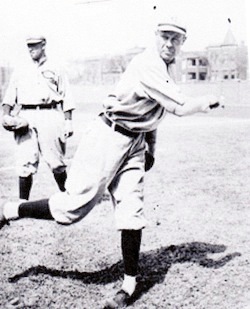

Emmett Eugene “Gene” Dale was born in St. Louis on June 16, 1889, the oldest of five children born to bricklayer Thomas J. Dale (1866-1958) and his wife, the former Sylvia Kahlert (1865-1959).1 Gene attended school through the eighth grade but little else is known about his early life. A willowy 6’3” and 179 lb., Dale began his playing career in 1908 with a team in the semi-pro St. Louis Trolley League, primarily as a right-handed pitcher with a three-quarters-to-sidearm throwing motion.

Fleeting newspaper references suggest that Dale subsequently received tryouts from a number of professional clubs, including the Chicago White Sox.2 In 1910, he signed with the Dallas Giants of the Class C Texas League. Highlights of Dale’s first professional campaign included a two-hit, 2-1 win over San Antonio on June 23, and a 6-1 no-hitter against Houston a month later. By season’s end, the 21-year-old had posted a 10-7 log in 204 innings pitched for the league co-champions.3

Dale’s performance piqued major leagues interest. Whirlwind off-season transactions moved Dale from Dallas to the Boston Red Sox to the Cleveland Naps to the Sacramento Sacts of the Pacific Coast League then back to Boston again.4 That spring, however, Dale did not make the Red Sox roster. Nor did he impress when later given a seven-game trial by the Providence Grays of the Class A Eastern League. Dale then returned to Dallas in the Texas League (which had upgraded from Class C to Class B) for the 1911 season. 5 He went 12-8, with an eye-catching 179 strikeouts, a performance that earned Dale a late-season look from the National League St. Louis Cardinals.

Gene Dale made his major league debut in Boston on September 19, 1911. Sent in by Cardinals manager Roger Bresnahan to protect a sixth-inning lead, Dale pitched two scoreless frames, only to be hammered for four runs in the bottom of the eighth. A ninth-inning St. Louis rally took Dale off the hook and produced a 13-12 Cardinals victory in a 2½ hour contest that Sporting Life labeled “a farce.”6 Four more Dale appearances, including two starts, yielded an unimpressive overall log of 0-2 with a 6.75 ERA in 14 2/3 innings pitched for the Cardinals, and prompted Dale’s return to the Dallas roster at season’s end.

Despite those numbers, Bresnahan liked what he saw from Dale. Accordingly, the Cardinals claimed Dale for themselves during the post-season, thereby preventing the Columbus Senators of the American Association from drafting him.7 Gene started the 1912 season with St. Louis but pitched ineffectively as both a spot starter and reliever. In 19 appearances covering 61 2/3 innings, Dale yielded 76 hits (including four homers) and 51 walks. In August, with his record standing at 0-5, with a 6.57 ERA, Dale was sold to the Montreal Royals of the Class AA International League. There, he finished the season passably, going 4-6 in 10 starts but with a decent walks/hits-to-innings-pitched ratio (1.300).

Dale’s next two seasons in Montreal produced mixed results. In 1913, he was a solid 13-10 as both a starter and reliever for a second-division (74-77) Royals club. The following year, both Montreal and Gene Dale saw their fortunes sink. The Royals were a non-competitive 60-89 in the IL, while Dale went 10-17, surrendering an unsightly 276 hits and 88 walks in 253 1/3 innings pitched.

His mediocre numbers notwithstanding, Dale was about to get another chance in the major leagues. The cellar-dwelling Cincinnati Reds were particularly weak in the pitching department and decided to hold mass auditions during 1915 spring training. Purchased from Montreal, Dale showed enough in camp to make the Reds’ Opening Day roster. He received scant attention once the season started, however, and was on the verge of being released without a trial when veteran backstop Red Dooin persuaded club brass to give Dale a chance to show what he could do.8 Several competent relief outings earned Dale a starting assignment. A 6-0 shutout that left Boston Braves batters “at a loss”9 put Dale in the ever-changing rotation of Reds manager Buck Herzog, who was chronically impatient with his pitching staffs.

Dale continued to pitch effectively despite being plagued by indifferent support,. On July 4, he shut out St. Louis 1-0, driving in the game’s only run himself. Eight days later, Dale whitewashed the Giants, beating Christy Mathewson, 6-0. Key to Dale’s success was mastery of a slow curve “with a sudden outward hop just at the end of the journey,” producing something akin to the celebrated Mathewson fadeaway.10

Although the seventh place Reds were out of the pennant chase early, Dale kept the good work going, finishing the season 18-17, with four shutouts and a sparkling 2.46 ERA. He paced the Reds staff in wins, ERA appearances (49) and innings, (296 1/3). He also had 104 strikeouts. About the only negative were the National League-leading 107 walks that Dale issued. At the mid-year mark, Sporting Life New York correspondent Harry Dix Cole deemed Dale the “only consistently good Reds pitcher,”11 while at year’s end Baseball Magazine pronounced Dale and the Cardinals’ Lee Meadows “the best of all the new pitchers snared by the National League.”12

Sadly for Cincinnati, Gene Dale proved a one-year wonder. In 1916, Dale’s slow curve no longer befuddled NL batters. After being hit hard in several early season starts, Herzog demoted him to the bullpen. Dale made his situation worse, by not handling adversity well; he often complained about a lack of support by Reds teammates. On July 2, Dale took the hill to start the nightcap of a home doubleheader against Pittsburgh and was hit hard again. After five innings the game was called because of inclement weather, leaving the Pirates a 6-1 victor.

In the clubhouse, Dale renewed his complaints about lack of support to an unsympathetic Herzog. The encounter concluded with the Reds manager ordering Dale to remain behind in Cincinnati while the club travelled to St. Louis, Dale’s hometown. Defying orders, the unhappy hurler made his own way home, publicly declaring that he “was through with baseball.”13 As soon as news of Dale’s insubordination reached Reds president Garry Herrmann, Dale was suspended indefinitely without pay.14 Days later, Dale’s contract was sold to the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association. At the time, the Dale log for the 1916 NL campaign stood at 3-4, with a 5.17 ERA in 69 2/3 innings pitched.

At 27, Dale’s major league career was over.. In parts of four seasons, he went 21-28 (.429), with a 3.60 ERA in 442 2/3 innings pitched. Almost all of his good work occurred in a single season, his sterling 1915 campaign with the Reds. His professional playing days, however, were far from done. In time, Dale reported to Indianapolis where he posted a 2-2 mark in six late-season games. In 1917, Gene started the season with Indianapolis but was soon demoted to the Denver Bears of the Class A Western League. A fine 14-5 log there earned Dale a return to Indianapolis where his 4-3 record and 3.04 ERA down the stretch helped the Indians to the American Association pennant.

In the ensuing Junior World Series against the International League champion Toronto Maple Leafs, the good-hitting Dale – he had batted a cumulative .368, with 15 extra-base hits, while pitching for Denver and Indianapolis that season – was the Game 1 right fielder for the Indians. He went two-for-five in an 8-2 Indianapolis victory. He pinch-hit in Game 2, but didn’t get a hit. Gene did not pitch during the Series, won in five games by Indianapolis, but took the mound in a post-Series exhibition game played by the two clubs.

In the ensuing Junior World Series against the International League champion Toronto Maple Leafs, the good-hitting Dale – he had batted a cumulative .368, with 15 extra-base hits, while pitching for Denver and Indianapolis that season – was the Game 1 right fielder for the Indians. He went two-for-five in an 8-2 Indianapolis victory. He pinch-hit in Game 2, but didn’t get a hit. Gene did not pitch during the Series, won in five games by Indianapolis, but took the mound in a post-Series exhibition game played by the two clubs.

Dale returned to Indianapolis for the 1918 American Association season, which was shortened because of World War I. He went 2-3 in 42 innings pitched, but with an outstanding 1.50 ERA. Dale reported for military duty after the season terminated on July 21 and was assigned to an infantry unit at Camp Jefferson, Missouri, a bus ride from St. Louis. When hostilities ended, Dale returned to baseball in 1919 with Indianapolis but was released after two losing efforts. Dale then signed with the Salt Lake City Bees of the high octane Pacific Coast League. Now featuring a shine ball, he went 13-13, with a 4.48 ERA for the Bees. Always a good hitter, Dale also chipped in a .325 batting average with two homers for the third place (88-83) Salt Lake club.

The 1919 PCL pennant race was essentially a two-team affair between the Vernon Tigers and the Los Angeles Angels. Pivotal to Vernon’s ultimate triumph was the capture of nine of 11 late-season games played against Salt Lake that featured three ineffectual outings from Dale. After the season, it was rumored that Salt Lake laid down against Vernon, and an investigation quietly ensued. On August 3, 1920, PCL president William H. McCarthy stunned West Coast baseball followers with the announcement that a number of prominent players, including Salt Lake outfielder Harl Maggert and Vernon team captain/first baseman Babe Borton, had been indefinitely suspended pending further inquiry into game-fixing and gambling allegations. From there, the scandal quickly mushroomed, with other PCL stalwarts, including Gene Dale, being implicated in the affair. The legitimacy of Vernon’s 1919 PCL pennant was placed in serious question, although it was never invalidated.15

Dale had been traded to the Dallas Submarines of the Texas League in exchange for pitcher Eddie Matheson by the time the scandal erupted. When his name surfaced in connection with the burgeoning PCL scandal, Dale denied that he had engaged in any underhanded conduct. As for his late-season losses to Vernon the previous season, Dale insisted that the game outcomes were decided “through better playing by [the Vernon] club.”16 But soon, leaked grand jury testimony put a more sinister cast on Dale’s performance. Among other things, it was revealed that Dale and Salt Lake outfielder Bill Rumler had accepted $500 and $200 checks, respectively, from suspected fix paymaster Borton. The grand jury also came into possession of a suspicious letter that Dale had mailed to Borton near the close of the 1919 PCL campaign. Meanwhile, Borton, fearful of being made the scandal scapegoat, began spreading the blame around. First, he accused Maggert, Rumler, and Dale of accepting payoffs to dump the crucial Salt Lake-Vernon series. Thereafter, Borton implicated no fewer than 27 PCL players in various forms of misconduct.

Safely beyond the subpoena power of a grand jury sitting in Los Angeles, Dale posted a lackluster 15-18 record for Dallas in 1920, but with a fine 2.61 ERA over a yeoman 296 innings pitched. Once the season was over, however, Dale was under pressure to appear before the panel. Texas League president J. Lewis Morris directed the Dallas club to arrange Dale’s appearance before the grand jury, with the league to cover his traveling expenses. If Dale did not appear, he would be barred from playing in the Texas League.17

Dale, however, wanted no part of California. Instead, he retreated home to St. Louis, maintaining, improbably, that he was needed in connection with the 1920 presidential election. The closest thing to testimony the grand jury received from Dale was an affidavit in which he averred that the $500 check from Borton was not a bribe, but the repayment of a loan Dale had made during the suspicious September 1919 series between Salt Lake and the Tigers.18 Dale subsequently reiterated his claim of innocence before a gathering of minor league officials in Kansas City, most of whom were unimpressed.

On December 11, 1920, the Los Angeles County grand jury returned gambling-related criminal charges against Babe Borton, Harl Maggert, Bill Rumler, and Nate Raymond, the West Coast gambler who purportedly bankrolled the underlying game-fixing. Gene Dale, however, was not charged, the grand jury apparently having had jurisdictional concerns in his case.19 The charges, however, were short-lived. Two weeks later, Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Frank R. Willis determined that, while reprehensible, the fixing of professional baseball games was not something prohibited by California criminal statutes. Such conduct was, at most, a breach of the player’s contract with his ball club, a matter for civil courts to deal with. The PCL scandal indictments were therefore dismissed.20

The Willis decision outraged baseball officials. More than a hint of what was in store for the players was embodied in the remarks of PCL president McCarthy. Despite the court’s ruling, the accused players “stand indicted and convicted in the eyes of the Coast League baseball public. If the law cannot punish them, it remains to baseball to do its share … and keep them from participating in the professional ranks,” he declared.21 The action demanded by McCarthy was not long in coming. On January 12, 1921, the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues, then the governing body of minor leagues baseball, formally expelled Babe Borton, Harl Maggert, Bill Rumler, and Gene Dale from Organized Baseball.22 This ruling provided an instructive precedent for Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis in dealing with the soon-to-be-acquitted Black Sox.

Although banned from officially recognized baseball, the 32-year-old Dale still wanted to pitch. In 1921, he hooked on with the Cape Giradeau Capahas, a venerable semi-pro nine. Pitching mostly on Sundays, he drew rave reviews in the local press. At mid-season, the Southeast Missourian praised “the steadiness of Dale [whose work] convinces Cape Giradeau fans that he can be relied upon always but particularly in the pinches.”23 On August 13, 1921, a hurler named Dale pitched four innings of relief for the Newark Bears in a game against International League rival Buffalo, but this Dale was a collegian.24

That winter, “Jean Dale, widely popular hurler of the Capahas” was the guest of honor at a banquet sponsored by the Cape Giradeau Chamber of Commerce, telling admiring fans that the local club would have “first claim on me for 1922.”25 From there, the life trail of Gene Dale grows fainter. Long a bachelor, Dale married an Iowa woman with the unusual first name Glen (maiden name unknown) sometime in 1929. The 1930 US Census lists Gene and Glen Dale living in Chicago, with Gene working as a building laborer. By 1935, he was back in St. Louis living with his parents, the fate of his marriage unclear.26 Dale lived quietly in his hometown, with his parents and brother Lawrence and working as a plater for Steel Products Company of St Louis.

On March 20, 1958, Gene Dale died from complications attending an obstruction of the gall bladder at Barnes Hospital in St. Louis. He was 68. Following funeral services, his remains were interred at Valhalla Cemetery. Without children, Dale was survived by his aged mother, sister Irene Dale Feuerbacher, and brothers Thomas and Lawrence. Brief obituaries published locally took note Gene Dale’s major leagues playing career, particularly his tenure with the Cardinals.27 No mention was made, however, of the ignominious end of his days in organized ball.

Notes

1. The biographical details of this profile have been culled from various sources including the Gene Dale file at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; US Census data, and certain of the newspaper articles cited below, particularly a profile of Dale by Bob Lemke, published in Sports Collectors Digest, September 3, 1993. Newspaper reportage often referred to Dale as Jean Dale, the name that he signed to his World War I draft registration card and reported to later-life census takers. But Gene Dale is how the player is identified in most baseball references and that will be the moniker utilized herein. The younger Dale children were Irene (born 1891), Thomas (1896), Dolly (1902), and Lawrence (1908).

2. The White Sox tryout was apparently based on the recommendation of Sox catching prospect Medric Boucher, according to the Decatur (Illinois) Daily Review, June 9, 1909. Like Dale, Boucher was a St. Louis native and had caught Dale several times during the Fall of 1908.

3. Both Dallas and Houston finished the 1910 Texas League season with an 82-58 mark, but there appears to have been no playoff to determine an outright league champion. See The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds. (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 2d ed., 1997) 169.

4 In time, the National Commission disapproved these transactions and formally reprimanded the Cleveland club, finding that the Naps had acted as a covert agent of the Red Sox rather than in its own interests, thus violating player draft protocols, as per Sporting Life, January 18, 1911. But curiously, the commission took no action when Dale started the 1911 season with the Sox, the club which had instigated the Dale transfers.

5. As noted in Sporting Life, August 11, 1911, and the Syracuse Herald, November 16, 1911. The Dale progression from club to club is also traced in note cards contained in the Gene Dale file at the Giamatti Research Center.

6. Sporting Life, September 25, 1911.

7. As per Sporting Life, October 11, 1911, and the Syracuse Herald, November 16, 1911.

8. As subsequently recounted in the Adams County (Iowa) Free Press, August 28, 1915.

9. The observation of Sporting Life, May 27, 1915.

10. As per Baseball Magazine, Vol. 15, October 6, 1915. Other published comments also rhapsodized about the Dale slow curve, a pitch that “floats over the pan and executes an amazing twist as it reaches the plate,” as per the Fort Wayne (Indiana) News, August 14, 1915, and Sporting Life, August 28, 1915.

11. Sporting Life, July 26, 1915.

12. Baseball Magazine, Vol. 15, October 6, 1915.

13. As reported in the Nevada State Journal/New York Times/Reno Evening Gazette, July 4, 1916, and elsewhere. For a more colorful account of the Dale-Herzog contretemps, see Donald Dewey and Nicholas Acocella, The Black Prince of Baseball: Hal Chase and the Mythology of the Game (Toronto: Sport Classic Books, 2004), 227-228.

14. As reported in the New York Times/Sandusky (Ohio) Star-Journal, July 4, 1916, and elsewhere.

15. A comprehensive account of the PCL scandal is provided in “The Bad News Bees: Salt Lake City and the Pacific Coast League Scandal of 1919,” by Larry R. Gerlach, Base Ball, A Journal of the Early Game, Vol. 6, No. 1, Spring 2012, 35-74.

16. As reported in the Washington Post, August 17, 1920, Ironwood (Michigan) Daily Globe, August 20, 1920, and elsewhere.

17. As reported in the Oakland Tribune, October 20, 1920, Los Angeles Times, October 21, 1920, and The Sporting News, November 4, 1920.

18. Gerlach, 59.

19. See Los Angeles Times, December 11, 1920. The physical absence of a grand jury target from the jurisdiction presents no legal impediment to his indictment. But to the extent that the grand jury felt otherwise, the Dale strategy of remaining outside the territorial limits of California was vindicated.

20. As reported in the Los Angeles Times/New York Times, December 25, 1920, and elsewhere. Six months later, the rationale of the Willis decision was expressly rejected by the Illinois Circuit Court Judge Hugo Friend in response to dismissal motions filed in the Black Sox case. In the meantime, the legislatures of various states, including California, adopted criminal statutes that explicitly outlawed the fixing of professional sporting contests.

21. As quoted in the Los Angeles Times, December 25, 1920.

22. As reported in the Atlanta Constitution/New York Times, January 13, 1921, and elsewhere. In his incisive essay on the PCL scandal, Larry Gerlach deems Gene Dale the most suspect of the Salt Lake players. The case against Bill Rumler, who adamantly maintained his innocence and had a facially plausible explanation for the $200 that he received from Borton, was far less persuasive. In 1929, Rumler was permitted back into the Pacific Coast League. The other three banned players, however, would remain excluded from organized ball.

23. Southeast Missourian, June 24, 1921.

24. As per “Bees’ Pitcher Stung Angels by Throwing Games,” by Bob Lemke, Sports Collectors Digest, September 3, 1993, 111.

25. Southeast Missourian, January 31, 1922.

26. The website of baseball necrologist Bill Lee indicates that Gene Dale’s remains were cremated and scattered on his wife’s grave. But Gene Dale has a headstone at Valhalla Cemetery in St. Louis, and there is no listing for his wife Glen Dale on the Valhalla Cemetery website. See www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=cr&cRid=32067.

27. See St. Louis Globe-Democrat/St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 22, 1958.

Full Name

Emmett Eugene Dale

Born

June 16, 1889 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

March 20, 1958 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.