Barney Gilligan

“Good field, no hit” is an assessment of an athlete with lopsided skills on the baseball diamond. In essence, his contributions are far greater on defense than offense. Many of these men were catchers. In fact, of the ten major-league players with the worst career batting averages (minimum 1,000 at-bats), six were backstops. Barney Gilligan is No. 8 on the list with a .207 mark. He fared much better with the primitive gloves of his era, the 1880s, than with his bat.

“Good field, no hit” is an assessment of an athlete with lopsided skills on the baseball diamond. In essence, his contributions are far greater on defense than offense. Many of these men were catchers. In fact, of the ten major-league players with the worst career batting averages (minimum 1,000 at-bats), six were backstops. Barney Gilligan is No. 8 on the list with a .207 mark. He fared much better with the primitive gloves of his era, the 1880s, than with his bat.

Gilligan, nicknamed Gilly, Gillie, or Mouse in baseball circles, was respected throughout the league for his catching skills, especially his strong arm. He routinely threw to bases when other catchers wouldn’t. Sure, this led to some errant throws, but it also dazzled the spectators and made the opposition cautious. Teammate Cliff Carroll made this assessment: “Rad [Hoss Radbourn] did things no pitcher will ever equal – certainly not under present [1898] rules. He had a catcher, too, who in my opinion was the greatest backstop that ever put on a mask – little Barney Gilligan. Of course, as an all-round ballplayer and a general jollier there never was another like Mike Kelly, but Gilligan as a catcher was the wonder of the day.”

Andrew Bernard Gilligan was born on January 3, 1856, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the sixth child of Ireland-born parents Patrick and Sarah (nee Martin) Gilligan. US Census reports show that Patrick and Sarah were in their 40s by the time of Barney’s birth and that Sarah would have another child at around 50. Andrew was called Bernard or Barney his entire life.

Sarah, born circa 1811, and Patrick, 1814, married on February 27, 1843, in Cambridge. Both were from what is now Northern Ireland. The patriarch supported the family as a laborer. Oddly, Barney and his sister Sarah are not listed with the family in the 1860 US Census.

Gilligan played for independent clubs in 1876 and ’77. Now a full-time catcher, Gilligan and a several teammates made the rounds with more than a few independent, Massachusetts clubs in 1878. In March they joined the Hudson club. Later they may have played with New Bedford. At some point they also joined the Unions of Somerville and the Alerts of Charlestown. By June they were with the Westboro club in a league that also included New Bedford, Worcester, Springfield, Holyoke, Lowell, and Manchester. In late July Westboro fell on hard times financially and sold out to interests in Clinton. (All the communities mentioned are in Massachusetts except Manchester, in New Hampshire.)

Gilligan’s teammates in 1878 included Gid Gardner, who was the main pitcher and sometimes captain; Tim Keefe, who was mainly an infielder and outfielder at this point in his career and would later make his mark as a Hall of Fame pitcher; Dan Cronin, also captain; Joe Quinn; Jerry Sweeney; and future major-league manager and umpire John Gaffney. Third base was manned by Billy Crook. After one of the best games of the season, in Springfield, Crook fell several floors down an airshaft and was killed amid horseplay with Sweeney. Future manager and acclaimed college coach Arthur Irwin took Crook’s place on the roster. The men made between $12 and $18 a week for their ballplaying skills.

In an interview with Frank H. Pope of the Boston Globe in March 1889, Clinton manager George T. Fayeweather described his catcher: “Gilligan’s great forte was foul tips. He was spry as a cat and ‘tip-and-out’ was just what his appetite craved all the time. He, too, was always ready to get to work and took great interest in his play.” In the same article, club president John Corcoran described a system batterymates Gilligan and Gardner devised for startling a batter, delivering the ball when he wasn’t ready – essentially quick-pitching. Pope wrote, “[Gilligan] would turn around as if to walk toward the fence, the batter would wait for him to get in position. Gardner would shoot the ball over the plate. Gilly would turn around and meet it and ‘one strike’ would send a shiver down the spinal cord of the batsman.” Thus, the batter was distracted and unprepared, and even if he swung, it would probably be meekly.

As an example of the pair’s effectiveness, the Fitchburg Sentinel commented in mid-September, “For the Clintons, Gardner pitched his usual fine game. Gilligan supported him in his tricky manner. Gilligan also did some fine batting, making a total of six bases.”

Purchased from Clinton in June 1879, Gilligan joined a National League expansion team, the Cleveland Forest Citys. The club had played the previous season as an independent. The Cleveland fans were initially dismayed to see the diminutive Gilligan take his position behind the bat, but his stellar play soon won the hearts of the crowd, and in fact he became a fan favorite. The fans were impressed with Gilligan’s handling of the speedy Jim McCormick’s pitches. According to the Chicago Tribune after his first game with the club, “Gilligan caught exceedingly well taking some fine pickups.” The Cleveland Leader wrote, “The wiry, agile little Gilligan caught the swift shoots of the big McCormick with an ease that made him a hero with the fans right from the start.” Gilligan, the newspaper added, “hops from side to side to meet McCormick’s twisters, snaps them like the grip of fate, throws to second base with wonderful quickness and precision and picks up foul bounds away off in the crowd and along the fence where no other catcher would think of looking for them. ‘Gillie’ is a brave boy.”

Cleveland finished in sixth place as McCormick and lefty Bobby Mitchell combined for a 27-55 record. Doc Kennedy worked the bulk of the games behind the plate, 46 games to Gilligan’s 27. Barney also appeared in 21 games in left field, batting a meager .171 in a total of 52 games. After the season, he barnstormed with other major leaguers who also called the Boston-area their hometown.

A returnee to the Cleveland lineup, Gilligan didn’t hit a lick again in 1880. In 30 games he virtually matched the previous season with a .172 batting average. Kennedy continued to work most of the games at catcher, 65 to 23. Cleveland as a whole fared much better. McCormick improved his record to 45-28 and led the team to a third-place finish, though a full 20 games behind Chicago, which ran away with the pennant. Gilligan wasn’t listed on Cleveland’s reserved roster at the end of the year.

Barney joined the Providence Grays for the 1881 season, backing up Emil Gross. After Gross went down with an injury in August, Gilligan took over the full-time duties. In all, Gross handled 50 games to Gilligan’s 36. Pitchers Monte Ward and Hoss Radbourn, spelled by Bobby Mathews, carried the club to a second-place finish, nine games behind Chicago. Gilligan batted a weak .219 in 46 games, but he impressed the main pitching corps of Ward and Radbourn, especially the latter, at the end of the year with his handling of their pitches.

In 1882 Gilligan became the club’s main catcher, backed up by Sandy Nava, the majors’ first Mexican-American player, for the first of three seasons. Providence held onto second place again, moving within three games of Chicago, which took its third straight championship. The Grays were in first place as late as September 15. In 1883 Providence again came close, five games behind leader Boston – but in third place. At the end of May Gilligan broke his finger while catching and lost two weeks. Regardless, he played a personal-best (up to then) 74 games at catcher, as he had the confidence of the club’s top pitcher, Radbourn, who started 68 games.

Radbourn was practically a one-man show in 1884, especially after mound mate Charlie Sweeney deserted the team in July. Radbourn pitched nearly every remaining game. His personal catcher, Gilligan, likewise stepped it up, working a league-leading 81 games to Nava’s 27; in fact, Rad favored Gilligan to the point that Nava was let go by September despite the looming postseason. The club directors had also soured on Nava, who hit only .095 – 11 hits in 116 at-bats and none for extra bases. Radbourn started 73 games and won 59 as Providence finally captured the pennant. Gilligan contributed his best season with the bat, setting career highs with a .245 batting average and 38 RBIs.

Providence participated in what amounted to the sport’s first World Series in late October agains the New York Metropolitans of the rival American Association. Radbourn, though worn and battered, won all three games despite the fact that they were all played in New York City. Gilligan caught each game; in fact, Providence used only nine players for the series. Barney made the most of the opportunity, going 4-for-9 with two RBIs, three runs scored, and two doubles.

Again, Gilligan was the team’s main catcher in 1885, working 65 games to Con Daily’s 48. Radbourn and Dupee Shaw each started 49 games but the Grays fell to fourth place, 33 games out, with basically the same lineup as in 1884.

In November Providence management sold out. The roster was picked up by the National League, fronted by Boston’s Arthur Soden, for $6,000. For his efforts and financial outlay, Soden kept Hoss Radbourn and catcher Con Daily for his Beaneaters. Soden chose Daily over Gilligan because the former was only 21 years old and the Boston executive believed that Barney’s arm had seen better days.

In February 1886 the league assigned Gilligan to the expansion Washington Nationals with Providence teammates Cliff Carroll, Paul Hines, Shaw, and Joe Start. Shaw and Gilligan held out in a salary dispute. Sporting Life noted in early April, “Mr. Gilligan and lady have come to adjourn in this city [D.C.] for the season. He has signed his contract.” The Senators may have been an expansion team in the National League, but they weren’t a new club. The team’s lineage dated to the Union Association, a third major league in 1884. In 1885 they held a slot in the Eastern League. The ’86 club was a conglomeration of the Eastern League nine and the Providence players. They were a poor club, ending with a 28-92 record in last place, 60 games out. John Gaffney, Gilly’s old teammate, was brought in to run the club on August 22. Gilligan was named captain and five new players were incorporated from the Hartford club of the Eastern League, including a 23-year-old catcher named Connie Mack, who made his major-league debut in September. Jack Farrell, another former Providence player, was acquired from Philadelphia for the stretch run.

Few around the league agreed with Soden’s assessment that Gilligan’s throwing arm was shot. Three quotes from Sporting Life that season highlight Washington’s delight with their full-time catcher. From June: “Gilligan has caught in thirty championship games, and is as fresh as the first game he caught. Besides playing a grand game behind the bat, he is hitting the ball lively and running the bases well.” In July the paper wrote, “Gilligan has recovered from his injury, and is at it again as hard as ever. He deserves great praise for his work. He tries for everything, and says that the goodwill of the spectators is worth a dozen averages, and he is correct.” In respect to his arm, “Gilligan is about the only catcher who is not afraid to cut a runner off at second with a man at third. He and [Jimmy] Knowles work together well in this particular.”

Gilligan was a tireless worker. He caught in 71 of the club’s games; no one else worked more than 14. He also appeared in 18 games in the field, but not by his choice. According to Sporting Life, “Gilligan does not relish playing in the [out]field. He says it is like being out of the corporation. He delights to take a hand in the interesting part of the ceremony.” His batting average dropped to .190. After the season, he opened a restaurant/bar in the District of Columbia.

Washington didn’t fare much better in 1887, finishing seventh. The 31-year-old Gilligan, nicknamed Mouse in Washington, lost his starting job to Connie Mack and even caught fewer games than Pat Dealy. In June Washington attempted to trade Barney to Philadelphia with Cliff Carroll but deal never went through as the pair raised a fuss because they both owned local saloons.

The team also battled charges of “crookedness” in 1887. Dupee Shaw was accused as early as May. Gilligan, as well, faced similar accusations, but they were unsubstantiated. Washington’s troubles stemmed from another source that became glaringly apparent in early September. According to the New York Times, “[Jack] Farrell and Gilligan failed to put in an appearance to play with Washington yesterday [the 5th]. Manager Gaffney will probably impose heavy fines.” Surprisingly, the disappearance came just days after a correspondent wrote for Sporting Life, “Gilligan is catching in his old-time style and is batting well. His throwing to the bases is quick and accurate, which shows that his arm has not lost its cunning.”

The following week Sporting Life explained of Gilligan’s absence, “During the early part of the week, the club was playing a series of games in New York, and it appears that Farrell and Gilligan broke over the ropes and engaged in a slugging match [drinking binge] …when they were booked to play. For this Gilligan, who was absent one day, was assessed the sum of $25, which was very low considering the offense.” Gaffney probably took it easy on his old teammate. That may have cost the manager. According to the Baltimore Sun, “Owing to the continued defeats of the Washington baseball nine, the management [has] decided on a new course of action. Gilligan and [Ed] Daily have been called home, and [George Shoch] and [Bill] Wright sent to Detroit to play [in their place]. Manager Gaffney will probably be superseded in a short time, and other changes are in contemplation.”

The Brooklyn Eagle presented a harsher assessment: “The Washington club is suffering now from the effects of condoning drunken habits in the ranks of its team. A correspondent of the Philadelphia Times, writing of that club’s affairs says: ‘Had the disposition to indulge in late hours and the flowing bowl been promptly checked months ago several men would not be on the verge of the blacklist and the standing of the club would be far higher. The slips of Farrell and others have been matters of comment for a long time, but a deaf ear has been turned by those in authority [until] the demoralization culminated a week since. As intimated last Sunday, the ax of discipline fell on Farrell, [Pat] Dealy and Gilligan for absence without leave and indulgence in the cup that inebriates.’ ”

Over the winter of 1887-1888, Gilligan was reserved by Washington but the club and catcher fielded offers for his services. Pittsburgh and Kansas City were suitors and Washington sought to trade Cliff Carroll and Barney to Boston for Ezra Sutton. None of the deals panned out and the Nationals eventually released Gilly at the turn of April. The Oshkosh Daily Northwestern relayed the following wire report: “[Cliff] Carroll was released by Washington last week. He and Barney Gilligan are both out in the cold; yet, both are good ballplayers. Fooling with whisky has cost them dearly.”

On April 25 Gilligan signed with Detroit. Gone from Washington, he sold his bar. On the 27th he met the Wolverines in Indianapolis and caught Lady Baldwin, going 1-for-5. It was his last major-league appearance. The Boston Globe summed up his performance: “Gilligan joined Detroit here [Indianapolis], and caught his first game of the season. His backup work was excellent, but his throwing to bases rather weak.” Gilligan hadn’t practiced all spring nor warmed up his arm properly. According to a wire report, “Indianapolis players ran pretty much as they pleased” in the 16-7 rout.

Barney finished his career with a .207 batting average, only 388 hits in 1,873 at-bats. It ranks in the top ten for lowest batting average for a major leaguer with 1,000 or more at-bats. Over parts of 11 seasons, he knocked only 94 of those hits for extra bases.

By June Gilligan had joined Lynn of the New England League, where he played in 11 games. On July 25 Lynn disbanded. Sporting Life reported, “Gilligan wants to play in Boston, but the Triumvirs [three Boston executives including Arthur Soden] say they have no use for him.” At the end of August the weekly commented, “[Gid] Gardner, Arthur Clarkson and Gilligan are playing with an amateur club in Cambridge, Mass. Excessively high salaries will bring many more good players to the same level.” This naturally makes one wonder whether the team was amateur or not. Soon thereafter, Gilly joined Manchester of the New England League. He appeared in three games in Manchester, for a total of 14 games in the New England League in 1888.

In August 1888 Gilligan appealed to the National League for back pay he believed Washington owed him from the latter part of 1887 after he was called home. The case was addressed at a league meeting. According to the Boston Globe, “In the case of Mr. Gilligan who appealed from the action of the Washington club in suspending him without pay during a portion of the season of 1887, after consideration of all the evidence presented, the case was dismissed.” Unsatisfied, Gilligan took the matter to court. When the Nationals hit Boston in September, Barney had their share of the gate receipts attached.

By this time and probably earlier, Gilligan had permanently relocated his residence to Lynn, Massachusetts, near Boston. In 1889 he played for Fitchburg and was also found on the Hyannis roster in July. The Sporting News found Gilligan in 1890 playing for “some jay town in New Hampshire.” He began 1891 with Lynn of the New England League, then joined the Newburyport, Massachusetts, club and then rejoined Lynn. He appeared in three games for Lynn. Sporting Life noted, “Barney Gilligan, the old Providence catcher, is right down to weight and plays a good game for Lynn.” In July, he was catching for the Warren club.

Gilligan retired to Lynn with his wife Sarah, a Canadian eight years his junior. She had immigrated to the United States in 1883; they were married about four years later. The couple had two children, both of whom died young.

Gilligan still listed “professional baseball player” as his occupation in the 1900 US Census. He may well have been playing semipro ball in and around Lynn. It appears that he was training or coaching with the Lynn club as late as 1905. According to Sporting Life in April of that year, “Barney Gilligan who caught Radbourne (sic) and other old-time pitchers … is limbering out daily with the Lynn team at Lynn. He has not yet forgotten the game.” Gilligan was 49 years old at the time.

In Lynn Gilligan worked as a garbage collector for the city sewer department for two decades. On April 1, 1934, at the age of 78, Barney Gilligan died from erysipelas, a bacterial infection of the skin, supposedly acquired after squeezing a pimple on his face. It was the same disease that later killed Miller Huggins. Gilligan was buried in Pine Grove Cemetery in Lynn.

Notes

I found no solid evidence that Gilligan’s first name was actually Andrew, as the reference sites claim. His name may indeed have been Andrew, but his family didn’t call him that, and he is listed in all places of reference that I found as Bernard. The 1920 US Census actually shows a name of Bernard M.

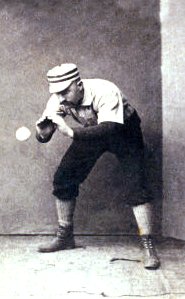

An 1892 Sporting Life reference states, “Smooth, clean shaven faces are the rule in the baseball profession. Quite a number wear mustaches but whiskers of the Andy Gilligan, Jerry Dunn pattern don’t flourish among the followers of the national game. There is not a player or umpire in the business wearing a full set of whiskers.” Just who were Andy Gilligan and Jerry Dunn? I’m not sure. Dunn may have been a boxer or boxing promoter but I can’t locate Andy Gilligan. He doesn’t seem to be the subject of this biography. Pictures of the 1878 Clintons and 1884 Providences show Barney Gilligan clean shaven. There is an 1887 Old Judge trading card from his time with Washington; it shows him wearing a mustache. He also wore a mustache as an aging gentleman. There is a picture in the Boston Globe on May 13, 1925, that shows this.

Sources

Minor league stats were provided by Ray Nemec.

Ancestry.com.

Baltimore Sun, 1887.

Bangor Daily Whig and Courier, Maine, 1888.

Barnstable Patriot, Massachusetts, 1889.

Baseball-reference.com.

Bismarck Daily Tribune, North Dakota, 1888.

Boston Daily Advertiser, 1878.

Boston Globe, 1878, 1888, 1891, 1925.

Brooklyn Eagle, 1874-1875, 1887.

Chicago Tribune, 1879, 1888.

Cleveland Leader, 1879.

Daily Inter Ocean, Chicago, 1879, 1888.

Dewey, Donald, and Nicholas Acocella. Total Ballclubs: The Ultimate Book of Baseball Teams. Wilmington, Delaware: Sports Media Publishing, Inc., 2005.

Egan, James M. Jr. Baseball on the Western Reserve: The Early Game in Cleveland and Northeast Ohio, Year by Year and Town by Town 1865-1900. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2008.

Fitchburg Sentinel, Massachusetts, 1878-1879.

Fort Wayne Gazette, Indiana, 1882.

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, eds. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Second Edition. Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 1997.

Lewis, Franklin A. The Cleveland Indians. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2006.

Logansport Pharos, Indiana, 1888.

Los Angeles Times, 1888.

Lowell Daily Citizen, 1878-1879.

Mitchell Daily Republican, South Dakota, 1886.

Morris, Peter. A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball, The Game on the Field. Chicago, Ivan R. Dee, 2006.

New York Times, 1875, 1883, 1887.

Oshkosh Daily Northwestern, Wisconsin, 1888.

Retrosheet.org.

Society for American Baseball Research. The SABR Baseball List and Record Book. New York: SABR, 2007.

Sporting Life, 1885-1905.

The Sporting News, 1890.

St. Louis Globe-Democrat, 1886-1887.

Washington Post, 1887-1888.

Full Name

Andrew Bernard Gilligan

Born

January 3, 1856 at Cambridge, MA (USA)

Died

April 1, 1934 at Lynn, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.