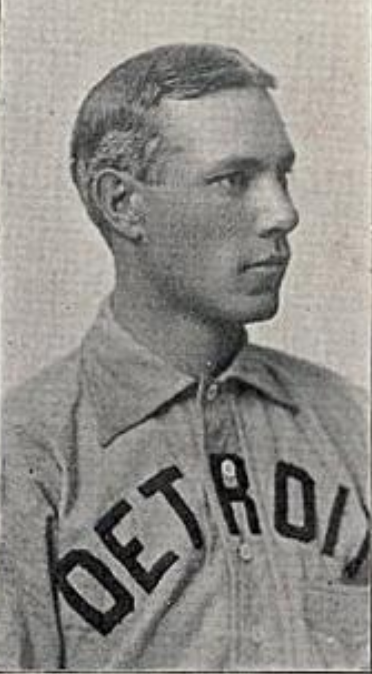

Pop Dillon

Many recognize Pop Dillon as merely a cousin of Hall of Famer Clark Griffith who happened to have a brief major league career. If he’s written about today, it’s usually in that context or in relation to his passing on a young fastballer named Walter Johnson. Dillon was in fact among the top names in California baseball during the first two decades of the twentieth century. He was a hard hitter and one of the top fielding first basemen on the coast. Dillon was also a respected field manager who led his club to four Pacific Coast League pennants. His 1903 nine ranks among the top minor league clubs of all time, with a 133-78 record.

Many recognize Pop Dillon as merely a cousin of Hall of Famer Clark Griffith who happened to have a brief major league career. If he’s written about today, it’s usually in that context or in relation to his passing on a young fastballer named Walter Johnson. Dillon was in fact among the top names in California baseball during the first two decades of the twentieth century. He was a hard hitter and one of the top fielding first basemen on the coast. Dillon was also a respected field manager who led his club to four Pacific Coast League pennants. His 1903 nine ranks among the top minor league clubs of all time, with a 133-78 record.

Dillon matched a still-unbroken major league record on Opening Day 1901 when he placed four doubles. That day, he knocked in the winning run, claiming the victory in the Detroit Tigers’ first game in the major American League. Three years later, he was at the center of a contract dispute that for a time threatened the fragile peace between the Pacific Coast League and organized baseball.

Frank Edward Dillon was born in Normal, Illinois on October 17, 1873. Normal, then known as North Bloomington, was located at the intersection of the Illinois Central and the Chicago & Alton Railroads. Business was booming in the area by the 1880s, as the town became a hub for the canning and shipping of berries, small fruits and vegetables. The Dillon family was among the most prosperous; they operated a profitable horse-rearing business that they brought to the area shortly after the Civil War. Isaiah Dillon and his younger brother Levi began breeding horses in the 1850s, becoming well known throughout the country. They lucratively imported, bred and sold the animals, as one of the nation’s first importers of Norman Draft horses.

Frank was the son of Levi Dillon and Mary Wright Dillon. Mary was the sister of Sarah Wright Griffith. After Sarah’s husband passed away, her family suffered though a harsh decade in the Missouri countryside. Around 1882, she brought her family back to Bloomington to open a boardinghouse and find a better climate for her sickly son Clark. At this time 8-year-old Frank met his 12-year-old cousin Clark for the first time. They soon bonded over their love of baseball, a profession that would establish Frank as one of the top personalities on the west coast and Clark Griffith as one of the leading figures in the game through eight decades.

Dillon grew up in the Bloomington/Normal area, attending local public schools. He then enrolled at Illinois State Normal University, the present-day Illinois State University, in 1892. Founded in 1857, it was the first publicly funded institution of higher education in Illinois. Dillon, a right-handed thrower and left-handed batter, was primarly an outfielder, but he took up pitching at the university. He played right field and was a substitute pitcher.

In the fall of 1893 he transferred to the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He joined the football squad and found a slot in the spring as the baseball team’s second pitcher. He pitched at Madison through 1894, gradually increasing his time on the mound. He graduated from the school in 1896, despite an incident in October 1895 when he was suspended for three months with some other students for mischievously interfering with freshman during their military drills.

After the spring semester in 1894, Dillon joined his first professional team, Peoria in the Western Association, a member of organized baseball. He appeared in 24 games for the club. No longer eligible as a college amateur, Dillon signed with his hometown Bloomington team in the Western International League in 1895, pitching and playing the infield. After nine games, he jumped to Ottumwa in the independent Eastern Iowa League in May with several teammates. He appeared in only five games with the club through the end of July. In early August the Jacksonville, Illinois club in the Western Association collapsed and Bloomington was slated to take their spot in the league. Dillon signed with his hometown team on August 6 but when Springfield, Illinois actually assumed Jacksonville’s slot he joined Dubuque of the same league. He pitched and played outfield with the club through the end of the season, appearing in 19 games.

Dillon spent 1896-97 with Rockford in the Western Association. By this time, he had abandoned pitching altogether and played strictly in the outfield. In 187 games with Rockford he batted a solid .320. Dillon didn’t join his club until June in 1897 because he was teaching and coaching girls’ basketball at Normal University. He also did some teaching at Ohio Wesleyan University over the winter of 1898-99. In 1898 he remained in the Western Association but moved to Rock Island, as the league withdrew from organized baseball.

Dillon began 1899 with Scranton in the Atlantic League, a top minor league. He appeared in 61 games for the club as a first baseman, the position he would play for the next decade and a half. On July 3, just before Scranton disbanded, Dillon and Louis Lippert were traded to Buffalo in the Western League for Bill Massey and Ed Householder. By this time, Dillon was gaining a reputation as a heavy hitter and excellent first baseman. He hit .309 with Scranton and .311 in sixty games with Buffalo. On September 6 he was purchased by the Pittsburgh Pirates for $1,500.

Dillon made his major league debut on the 8th, knocking two hits including a double and scoring twice against Louisville. He played virtually every remaining game for the club. In thirty games he knocked in 20 base runners. Dillon rejoined the Pirates in Thomasville, Georgia for spring training in 1900. However, events over the winter undermined his chances of making the club. Louisville owner Barney Dreyfuss divested from the Colonels and purchased a block of stock in the Pittsburgh Pirates. Soon thereafter, fourteen Louisville players were sold to Pittsburgh in a syndicate deal which netted Louisville little. Among the fourteen that would soon establish a dynasty in Pittsburgh were Fred Clarke, Honus Wagner, Rube Waddell, Tommy Leach, Chief Zimmer, Claude Ritchey and Deacon Phillippe.

Fortunately, none of them were first baseman; however, on April 30 the Pirates purchased Duff Cooley from the Phillies. After only five games, Dillon was released as part of the Cooley announcement. Within a week he landed a job with Detroit in the American League, the renamed Western League. He was the club’s full-time first baseman, hitting .291 in 123 games.

Dillon maintained his position as the American League seized major league status in 1901. On Opening Day April 25, the Tigers’ first official game as a major, he matched a still-unbroken record by hitting four doubles. The Tigers entered the ninth inning down nine runs to Milwaukee. They rallied to win 14-13. Dillon knocked in the tying and winning runs with his fourth double of the day. His teammates carried him off the field in jubilation. In 74 games, all manning first base, he batted .288 and knocked in 42 runs. After the season, Dillon organized a club that barnstormed throughout Michigan.

An appendicitis attack landed Dillon in a Chicago hospital at the beginning of March 1902. He never fully recovered and was mired in a horrible slump. After 66 games with the club, Dillon was batting a meager .206. In July, when John McGraw abandoned his Baltimore club and absconded with much of its personnel, American League owners chipped in to fill the Orioles roster. Detroit sent Dillon, who arrived for the July 19 game. The Orioles used him for only two games, and then gave him his outright release.

In mid-August Dillon arrived in Los Angeles, where he was signed by club owner James F. Morley to play first base for the California League team. Dillon appeared in 83 games, hitting .340. At the end of the year Morley turned over his field management duties to Dillon. The club joined the independent Pacific Coast League in 1903. Cap Dillon, as he was popularly called, hit the ball hard all year, finishing with a .364 batting average and leading the league with 274 hits. The club, one of the best in minor league history, captured the pennant by a huge margin with a 133-78 record. Dillon wasn’t referred to as Pop until around 1911, in recognition of his years at the helm of the Los Angeles franchise and the fact that his hair turned gray by his late 20s.

In September 1903 Dillon resigned with Morley for the 1904 season. In December he also signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers and took $500 in advance money. Although this was not unique in baseball history, it caused quite a stir at the onset of 1904. Problem was, the Pacific Coast League was negotiating to join organized baseball. The Dillon issue became a sticking point, as Morley and the Dodgers manager Ned Hanlon refused to capitulate. Morley, ignoring pleas from other PCL owners, insisted on retaining Dillon even if it meant a continuing war with the major leagues. Hanlon on his part declared that if the player didn’t join Brooklyn there would be no national agreement with the PCL.

The PCL did in fact sign the National Agreement, but Morley and Hanlon refused to settle their dispute. The PCL even voted 5-1 to assign Dillon to Brooklyn. However, Morley persisted and Dillon suited up for Los Angeles on Opening Day March 24, but the umpire refused to allow him to take the field. Even after Morley presented a legal injunction barring the umpire from interfering, the umpire still refused to acknowledge Morley’s claim. Dillon sat on the bench for the contest and agreed to do so until the matter was settled. The umpire was arrested after the game, but the other PCL owners secured him an attorney to plead his case. The matter was then referred to the National Commission, organized baseball’s ruling body. The commission unanimously awarded Dillon to Brooklyn in April, despite the fact that Los Angeles had a prior claim. Morley appealed to the board but he was once again denied in May.

Dillon joined Brooklyn in late April 1904 and was named team captain, part of the original offer from Hanlon. He was a solid, if unspectacular, contributor to the Dodgers. In 135 games Dillon batted .258 with 31 RBI for perhaps the weakest hitting club in the league. Only three other Dodgers knocked in more runs. Teammate Johnny Dobbs at one time described Dillon as the finest hit-and-run man in the game. At the end of the year Dillon appealed to Hanlon for his release so he could rejoin Los Angeles. The deal was made in March 1905, with Morley paying $1,700 for his returning manager and first baseman.

Morley went toe-to-toe with the majors again in 1905. This time he didn’t want to cede his other first baseman, Hal Chase. He claimed Chase was drafted illegally by the New York Highlanders and thus signed him to a contract with the Angels for the upcoming season. Dillon was stuck in the middle of the argument, as this time the opponent was his cousin Clark Griffith, manager of the Highlanders. After barbs were traded in the press Griffith sent a representative to California to pull Chase away.

Dillon made a much-heralded error in February 1906 when he passed on a fireballer from Humboldt, Kansas named Walter Johnson because the young pitcher lacked experience, couldn’t hold runners on and “telegraphed everything he throws.” Johnson, whose family relocated to California in 1902, was set to meet with Dillon again the following year, but the pitcher was too timid to approach the manager while he was playing a game of billiards. Dillon finished his game and left without knowing that Johnson was even in town. Johnson ended up playing ball for a few dollars in Idaho. Eventually, the big, shy country boy had to be virtually dragged to the east coast to join the Washington Nationals of the American League to begin his storied major league career.

The Angels won three more Pacific Coast League pennants under Dillon in 1905 and 1907-08. He remained with Los Angeles as manager through 1915. He was mentioned at least once as a potential major league manager. With the Reds unhappy with their circumstances, rumors surfaced in 1911 that Garry Herrmann was looking at Dillon to possibly replace his manager, Clark Griffith. After Griffith joined the Senators, Dillon was hired as a west coast scout for the club and occasionally held players on the Los Angeles roster as an unofficial farm club.

Dillon played first base regularly through the 1912 season. He continued to pinch hit and play first sporadically for three more seasons. After the 1915 season, the club started looking for a new manager. Seeing the writing on the wall, Dillon retired in November. In nearly 2,200 minor league games he batted a respectable .295 with over 2,300 hits.

Dillon married a fellow Illinoisan, a bookkeeper from Freeport born in May 1880, Blanche Ada Reitzell. They were married in Berkeley, California on August 15, 1903. The Los Angeles club was riding so high at the time, ultimately winning the pennant by 27.5 games, that the Dillons took off for a mid-season honeymoon. They moved to Los Angeles permanently in 1905 after Dillon returned to the club. The couple never had children. The Dillons purchased an apple farm in Yucaipa, California, in San Bernardino County, and retired there after baseball. He played a great deal of golf in retirement. In the 1920s the couple returned to Los Angeles where Dillon found employment as a baker.

Dillon remained close to the game. He coached baseball at Occidental College in Los Angeles in 1917. In 1922 he was part of a group that built and taught at a baseball school/camp in Burbank. The following season he attempted a comeback, trying to land with a club as a coach. It didn’t work out, but he soon became treasurer of the Association of Professional Ball Players of America, an organization formed in 1924 to provide a financial boost to retired needy ballplayers and others associated with the game. He worked for the APBPA from the time of its formation until his death. Remaining in good shape, he hosted and played in numerous old-timers contests benefitting the APBPA.

In 1929 Dillon signed to manage the Ventura club in a new four-team Class-D league; however, the venture never got off the ground. Just before his death, Dillon published a book titled, How to Play Baseball and Inside Baseball.

Frank Dillon passed away after a long illness at age 57 on September 12, 1931 at Fitch’s Sanatorium in Pasadena, California. He was interred at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale.

Sources

Ancestry.com

Baseball-reference.com

Boston Globe

Chicago Tribune

Daily Inter Ocean, Chicago

Daily Review, Decatur, Illinois

Evening News, Lincoln, Nebraska

Hartford Courant

Johnson, Lloyd. The Minor League Register. Durham, North Carolina: Baseball American Inc., 1994.

Johnson, Lloyd and Miles Wolff. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Second Edition. Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 1997.

Los Angeles Times

McKenna, Brian. Clark Griffith: Baseball’s Statesman, forthcoming biography.

Milwaukee Journal

Milwaukee Sentinel

Moberly Evening Democrat, Missouri

Nebraska State Journal

New York Times

Oakland Tribune

Oshkosh Daily Northwestern

Retrosheet.org

Sporting Life

Thomas, Henry W. Walter Johnson: Baseball’s Big Train. Washington D.C.: Phenom Press, 1995.

Washington Post

Full Name

Frank Edward Dillon

Born

October 17, 1873 at Normal, IL (USA)

Died

September 12, 1931 at Pasadena, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.