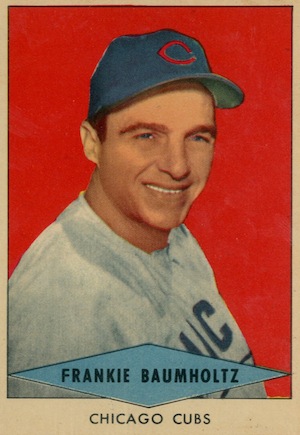

Frank Baumholtz

For most people, spending a decade as a reliable major leaguer with a .290 career batting average would stand as the achievement of a lifetime. But the argument could be made that Frank Baumholtz’s baseball accomplishments ranked third behind a standout basketball career and an impressive record of service in World War II. However you stack them up, the pioneering two-sport star compiled quite a résumé, especially for someone who didn’t even crack the big leagues until he was 28.

For most people, spending a decade as a reliable major leaguer with a .290 career batting average would stand as the achievement of a lifetime. But the argument could be made that Frank Baumholtz’s baseball accomplishments ranked third behind a standout basketball career and an impressive record of service in World War II. However you stack them up, the pioneering two-sport star compiled quite a résumé, especially for someone who didn’t even crack the big leagues until he was 28.

Frank Conrad Baumholtz II was born on October 7, 1918, in Midvale, Ohio, one of five children, three boys and two girls. His parents, Frank and Katherine, emigrated from Central Europe and settled in Ohio.1 Midvale, about 90 miles south of Cleveland, was home to the Robinson Clay Products sewer pipe plant. Frank Sr. was a pipe inspector at the plant, using a hammer to determine whether clay sewer pipes that had emerged from the kiln and cooled were usable.2

The family lived in company housing when Frank was young. They had no electricity and used lamps to light each room. The lamps could be mounted in rings on the walls – rings that, when empty, prompted young Frank to take up basketball in its most primitive form with help from a small rubber ball. Eventually he procured an old sweet-potato basket from a grocery store, knocked out the bottom, and nailed it to a post near his house. Dr. Naismith would have been proud.

With endless practice, Frank quickly became a standout among the neighborhood kids – and not just in basketball. By the time he reached Midvale High School, he also ran the mile and half-mile, threw the shot, and pole-vaulted for the track team, in addition to pitching and playing first base and the outfield for the baseball team.3 He earned 12 varsity letters.

Basketball provided the escape Frank desperately sought. “I wanted to get away, as I got older, from the poverty of the area that we lived in,” he said. “We didn’t have any money, and I was determined that somehow I was going to go to college. … I was determined that I was going to play baseball and basketball. I was determined, and worked at both of them, that I was going to play professional. It happened to all work out in my favor, but it wasn’t just because I wanted to, it’s because I worked at it, and that’s the only reason.”4

Midvale was good enough to play deep into the Ohio state basketball tournament, making it all the way to Columbus, and Frank’s performance caught the eye of college coaches around the region. He ultimately decided he’d rather stay close to home and signed on with Ohio University.

Freshmen weren’t eligible to play on varsity squads in those days, so Baumholtz spent the 1937-38 season on the freshman team coached by Dutch Trautwein. They all moved up together the following season, with Trautwein taking over as varsity coach, and went 12-8 in 1938-39, then improved to 19-6 the next season.

Baumholtz’s junior year was notable in one other key aspect: His future wife, Bettie Marie Bell, finally agreed to go out on a date with him after a lengthy pursuit. He had initially asked her out after spotting her in his first college class, but she declined – and continued to do so on and off for the next two years, citing a boyfriend back home in Cleveland. She finally acquiesced and agreed to accompany him to a hayride. Trautwein happened to be chaperoning the event, and he was surprised to learn from his star player that the two were on their first date, noting that the pair acted as if they’d known each other all their lives. Baumholtz responded that he intended for them to know each other the rest of their lives.5

With his personal life squared away, Baumholtz continued his rise to stardom, and had an unforgettable senior season. The 5-foot-10, left-handed guard led Ohio U. to a 16-3 regular-season mark that earned the Bobcats a spot in the pre-eminent postseason affair of the day, the National Invitation Tournament at Madison Square Garden. Baumholtz left New York sportswriters enraptured with his small-town tale.

Gushed Tim Cohane of the New York World-Telegram: “Baumholtz is a little fellow with great speed and drive, a Hollywood profile and a greater variety of pleasing shots than a techni-color movie. He canned one-handers, two-handers, set shots and lay-ups, three in the first half and six in the second. He has a terrific head start on the Tournament’s Most Valuable Player Trophy.”6

Cohane proved prescient. Baumholtz scored 12 in a 45-43 semifinal win over City College of New York and 19 in a 56-42 loss to coach Clair Bee’s Long Island University Blackbirds in the final, and he was named MVP despite his team’s runner-up status.

If making a career out of pro basketball had been as viable an option then as it is today, Baumholtz might have stuck with the hardwood. But he knew what he had to do if he wanted to become a professional athlete, and his focus shifted back to the diamond. “My love for basketball kind of overshadowed my baseball career,” he said, “but I never forgot the fact that I was going to be a big-league baseball player.”7

The Cincinnati Reds’ area scout was a regular presence at Ohio U. baseball games, and assistant general manager Frank Lane eventually signed Baumholtz and Bobcats teammates Ernie Kish and Ray Farroni on June 1, 1941.8 Baumholtz got $1,000 to sign, and his salary that summer was $125 a month.9

The trio headed to Riverside in the Class C California League, where Baumholtz hit .278 in his first 19 games as a pro before the Riverside franchise folded on June 29. Baumholtz was shipped to Ogden in the Pioneer League to finish out the season, hitting .283 in 74 games there. Nothing spectacular, but not a bad start for a guy known more as a basketball player.

Here a slight detour was in order. The Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 instituted the first peacetime draft in US history. Baumholtz thought he might enlist in the Army or Navy and get his one-year hitch out of the way instead of waiting to be drafted. Like other notable athletes in similar positions, he had been receiving letters from the Great Lakes Naval Training Station, outside Chicago, urging him to join the Navy there while contributing to the burgeoning Great Lakes sports program. On October 8, 1941, Baumholtz enlisted in the Navy. He couldn’t have imagined at the time that he wouldn’t be back in Organized Baseball until 1946. Two months later the US was at war.

In the spring of 1942 Baumholtz went out for the Great Lakes baseball team, which would grow to become arguably the best squad anywhere over the next few years as military commitments depleted major-league rosters. Baumholtz made the team, joining major leaguers like Johnny Lucadello, Joe Grace, Don Padgett, Benny McCoy, and Frankie Pytlak under the direction of Lieutenant Mickey Cochrane. He was in the starting lineup when the Bluejackets opened their season on April 28, and he tripled and scored in a 13-4 rout of Indiana University.10

Baumholtz was in line to make the roster11 for a July 7 benefit game between an Army-Navy all-star team and the American League All-Stars at Cleveland Municipal Stadium. But on July 2 he was commissioned an ensign and received orders to report to the Armed Guard School12 at Naval Station Treasure Island in San Francisco. This was where Baumholtz’s path diverged from that of many of the ballplayers who joined the armed forces in World War II. Many of the more established players spent their time in physical-education programs and staging exhibitions to boost the morale of other troops. But the combination of Baumholtz not yet being established as a major-league player and the fact that he had a college degree, which helped him gain his commission, put him on track for the kind of combat duty that many Great Lakes players never had to face.

The Armed Guard was responsible for protecting merchant ships from attack by enemy planes, ships and submarines. Armed Guard officers led Navy gunnery teams of about two dozen that worked in concert with the civilian seamen they were assigned to protect – “a kind of doctor, chaplain and commanding officer at the same time,” as a Navy history put it.13 Aside from a short break that allowed him time to rush home to Cleveland and marry Bettie Bell, Baumholtz spent much of the period from late 1942 through the spring of 1944 on ships making convoy runs across the Atlantic.

By the summer of 1944, Baumholtz was a lieutenant commanding a new Landing Craft Infantry (Large) vessel. LCI(L)-633, launched a week after the June 6 D-Day landings in Normandy.14 On June 25 LCI(L)-633 embarked from Pier 42 in New York en route to the Pacific. Baumholtz and his ship – later converted to mortar duty and redesignated LCI(M)-633 – saw action in the final two major battles in the Pacific, providing fire support off Iwo Jima in February 1945 and Okinawa two months later. The 633 took a hit from a Japanese mortar at Iwo Jima but did not suffer major casualties. The crew witnessed more than enough of the war’s horrors close at hand. Baumholtz recalled being about 1,500 yards from the USS Birmingham when a kamikaze hit the cruiser, essentially knocking it out of commission through the end of the war.

In late August, with the war over, Baumholtz was given command of LCI Group 61.15 He had the opportunity to take a flotilla of ships back to Japan to serve with the occupying force, but he also had enough “points” accumulated to be discharged from the Navy. With very little contemplation, he chose to muster out and was back home in Ohio around the end of the year. But his war didn’t end for some time.

“People that were at Iwo Jima and Okinawa, it took me years and years to block those out of my mind, there were so many things that were happening,” Baumholtz recalled. “… Everything I blotted out of my mind except at night. Bettie used to say to me, ‘Wake up,’ and I’d say, ‘What?’ and she’d say, ‘You’re reliving the war.’ I’d say, ‘What do you mean reliving the war?’ She’d say, ‘You’re ordering your crew around, telling them to do this and do that, so and so’s here and you’ve got to do this and do that. You’re fighting the war in your sleep.’ It took a few years.” 16

It did not take long for Baumholtz to resume his athletic career. Days after returning home following his discharge, he got a call from the general manager of the Youngstown Bears of the National Basketball League, a forerunner to the NBA consisting mostly of teams in Midwestern cities. Baumholtz quickly settled into the Bears’ lineup and ended up averaging 10.5 points in 26 games, good enough to be named second-team all-NBL. But he didn’t finish the season with Youngstown.

He also had let Warren Giles, the Reds general manager, know he was out of the service and back to playing basketball and asking about his status with the Reds. He quickly received a reply reminding him he was still Cincinnati property and to report to spring training as scheduled. He did, leaving the Bears for the final dozen or so games of the season, and ended up breaking camp with Cincinnati after spring training. He stayed with the team for a month but did not play for Bill McKechnie’s club and finally was dispatched to Columbia of the Sally League in May.17

Baumholtz, 27, was the oldest player on the team, but he didn’t show much rust from his years away from the game. He hit .343 in 119 games for Columbia, second only to 21-year-old Ted Kluszewski (.352) among the regulars, and racked up 43 doubles and 13 triples along the way. That showing was sufficient to put him on the radar of the Reds brass heading into the winter – which, once again, Baumholtz spent on the court.

The Cleveland Rebels were an original member of the Basketball Association of America, which began play in the fall of 1946, and Baumholtz was a natural fit as one of six Ohio natives on the roster.18 He starred from the outset, scoring a game-high 25 points in the Rebels’ season-opening win against the Toronto Huskies.19 Baumholtz played 45 games for the Rebels that winter – making $4,000 for his trouble20 — and once again was named second-team all-league. His 14.0 points per game ranked as the eighth-best average in the BAA.

Even in the midst of another successful basketball season, though, the Reds were expecting big things from the two-sport standout. New manager Johnny Neun told the Associated Press in late January that he considered Baumholtz the top candidate to start in center field for Cincinnati. Neun even cited Baumholtz’s choice of offseason employment as a positive, saying, “He’s got to be pretty strong to take that pounding in pro basketball.”21

Baumholtz saw 1947 as a do-or-die year for his major-league aspirations. His basketball credentials were well-established, but he wasn’t keen on the prospect of continuing to bail on his teams before the end of the season to report to spring training, only to be stuck in the minors – essentially messing up both sports, as he put it.

Sure enough, that was the year Baumholtz finally established himself. Leading off for the Reds on Opening Day against the defending World Series champion St. Louis Cardinals, Baumholtz went 2-for-4 with a double and an RBI in his major-league debut. He went on to lead the National League with 711 plate appearances and ranked in the NL’s top five in hits (182), doubles (32), and triples (9) on his way to finishing a distant fifth behind Jackie Robinson in Rookie of the Year voting.

Baumholtz finished with a .283 batting average – a disappointment, as that year-end number was his lowest since it stood at .273 on April 23. He hit just .215 with a .585 OPS (slugging average plus on-base percentage) in September. Baumholtz’s explanation for the late fade was the stress of off-field problems. Bettie suffered a ruptured appendix late in the season and had to be hospitalized for weeks; for a while, he feared she wouldn’t survive. Shortly after that, her father died.22

It’s fair to say the Reds might have had another theory about the drop-off in Baumholtz’s performance: fatigue. Shortly before the season ended, Warren Giles called Baumholtz into his office. In his hands, upside down, was a check. The Reds wanted Baumholtz to stop playing basketball in the offseason, and they were prepared to pay him to agree.

Reports at the time suggested that the payoff was more than $6,000,23 but Baumholtz recalled years later that it was between $7,500 and $10,000. Either way, between that bonus and an increase in his baseball salary from $4,000 to $10,000 for the following season, he agreed to hang up his sneakers.24

Easing his offseason load didn’t help Baumholtz get out of the gate strong in 1948. He started the team’s first 21 games, but his average was down to .212 on May 9. Two days later the Reds acquired veteran outfielder Danny Litwhiler from the Boston Braves and made him their starter in right field. Banished to the bench, Baumholtz now saw most of his action as a pinch-hitter or defensive replacement.

He started to show signs of life at the plate in a few starts in June and regained his starting spot in early July. Riding a 12-game hitting streak, he was hit on the right elbow by a Larry Jansen pitch leading off the July 19 game against the New York Giants. X-rays were negative,25 but it was six days before Baumholtz was back in the starting lineup.

Those types of little, nagging injuries – some from being hit by a pitch, some from crashing into outfield walls – would pop up with some regularity throughout Baumholtz’s career. He wouldn’t approach the playing time he got as a 28-year-old rookie in 1947 for the rest of his big-league career.

In early August, on their way to a seventh-place finish on the heels of a fifth-place showing the year before, the Reds fired Johnny Neun and named Bucky Walters manager for the balance of the season. Walters re-signed for the 1949 campaign, but wouldn’t find much use for Baumholtz.

One of the few bright spots for the Reds in 1948 was the play of Hank Sauer, who pounded out 35 home runs in his first full season in the majors. Through the first six weeks of the 1949 season, though, both Sauer and Baumholtz were struggling at the plate. Bauer was hitting .237 with just four homers in 42 games, while Baumholtz was at .235. On June 15, the day of baseball’s trade deadline, the pair were dealt to the Chicago Cubs for Peanuts Lowrey and Harry “The Hat” Walker.

The change of scenery didn’t do much for Baumholtz. Two days before the trade, Frankie Frisch had replaced Charlie Grimm as manager of the Cubs. Frisch started Baumholtz only sporadically and the outfielder slumped to a .229 average to close the season, the worst year-end number of his career by more than 40 points. Decades later, Baumholtz repeatedly used the word “devastated” to describe his initial reaction to the trade and its aftermath,26 but the biggest shock was yet to come.

Hoping for a fresh start in 1950 as the Cubs went through spring training on Catalina Island, Baumholtz was stunned when Frisch told him he wouldn’t be making the trip back east with the Cubs. Instead, he would spend the entire year with Los Angeles of the Pacific Coast League – a demotion that ultimately got his career back on track.

Baumholtz caught fire at the plate from the very beginning with the Angels, embarking in late April on a 33-game hitting streak. “And they said he couldn’t hit!” Angels manager Bill Kelly enthused after Game 29 of the tear.27 Baumholtz hit .460 over the 33-game span.28

That early momentum propelled Baumholtz to a campaign that saw him easily win the PCL batting title with a .379 average. Though he flirted with .400 much of the season, the Cubs never did call him back. The following summer, with the outfielder finally back in Chicago and playing regularly, The Sporting News said Baumholtz’s “banishment to Los Angeles in 1950 is looked upon as one of the biggest rocks of the several of which the Bruin brass have been guilty.”29

Eighty games into the 1951 season, the Cubs fired Frisch and installed Phil Cavarretta as player-manager. Baumholtz later called Cavarretta the best manager he ever played for,30 and by this point it was clear he was back in his comfort zone. At the plate he was back around .300, and his offensive numbers at the end of the season were nearly identical to those from his rookie campaign four years earlier.

His major-league bona fides re-established, Baumholtz went on to have the best offensive season of his career in 1952, contending for a batting title into the final weeks of the season – but not without more trouble from the injury bug.

Baumholtz injured ligaments in his right shoulder attempting to make a shoestring catch at the Polo Grounds on May 17, and was sidelined for two weeks.31 Five days after returning to the lineup, he was hit in the right hand by a Warren Spahn pitch, breaking a metacarpal32 and sidelining him for six more weeks.

With their team finally back in the first division, Chicagoans did not take kindly to losing their top hitter. Shortly after Baumholtz was knocked out of commission, Spahn received a letter that included a clipping of a news account of the incident and threatened to “make good” on Baumholtz’s injury. “I’ll get you somehow,” the letter read. “You can be handled.” The letter was forwarded to the FBI, and when the Braves returned to Wrigley Field for a mid-July series, Spahn was assigned a three-man protective detail of Chicago police officers. The officers drove him between the hotel and the ballpark and one sat in the Boston dugout during the games.33

Baumholtz returned to the lineup shortly after Spahn escaped that trip to Chicago unscathed, and after a brief lull at the plate he was back above .300 again by mid-August. A month later, the unthinkable: Baumholtz found himself within striking distance of Stan Musial, who had been cruising toward his third consecutive batting title.

The Cubs’ final six games of the season were against the rival Cardinals, though with an unwieldy five-day gap between the series at Wrigley and the season-ending set at Sportsman’s Park. (The Cardinals hosted the Reds for three during that span.) On September 20, after the middle game of the series in Chicago, Baumholtz stood at .332 and Musial’s average had dipped to .333. But that was as close as Baumholtz got; he went 2-for-14 in the Cubs’ final four games to finish at .325, while Musial went 11-for-26 in seven games to hit the wire at .336.

The end did not come without a bit of a sideshow, though. In the season finale, September 28 in St. Louis, Harvey Haddix walked Cubs leadoff man Tommy Brown to open the game. Baumholtz was up next, and Musial came trotting in from center field to take the mound, with Haddix going to right field and Hal Rice shifting to center. Ensuring that the stunt was all in good fun, Baumholtz switched around to bat right-handed. He grounded Musial’s first pitch to third, where Solly Hemus booted it for his 29th error of the season. Everyone was safe – from out, from injury – and the Cardinals returned to their conventional alignment after the lone major-league mound appearance of Musial’s career.34

Baumholtz had one big offensive season left, hitting .306 and racking up 36 doubles in 1953. That was the first of consecutive seasons that saw Baumholtz, at age 34 and 35, serve as what passed for the wheels in the Cubs outfield. He spent more time in center field than he had in recent years, and was flanked by Sauer and Ralph Kiner, neither of whom was getting paid for his work with the leather. Chicago’s defensive alignment became a favorite talking point of sportswriters of the time and the legend of poor Frankie in perpetual motion around the Wrigley Field grass would persist for decades.

A chance hotel encounter with a Chicago Tribune reporter in 1969 led to a newsman’s throwaway line about how playing between the two sluggers drove Baumholtz out of baseball, though Baumholtz defended his pal Sauer’s fielding.35 Seventeen years later, he gave the same newspaper almost the same quote on the matter: “People always kid me about the way I had to run my legs off making catches for Kiner or Sauer, but it wasn’t that tough. When Sauer played left field, he was a pretty good outfielder.”36

Baumholtz went 15-for-37 as a pinch-hitter in 1955,37 establishing a late-career niche that he continued after being sold to the Phillies in December of that year. He appeared in 76 games in 1956, starting only 12 of them. Along the way he recorded 27 hits – all of them singles. That was pretty much the end of the line for Baumholtz, who went hitless in a pair of pinch-hit appearances for the Phillies in 1957 before hanging it up at the age of 38. He finished his career with a .307 average as a pinch-hitter.38

In the end, Baumholtz could be secure in his status as a good player in what has often been called the golden age of the sport, with the likes of Musial, Ted Williams, and Joe DiMaggio among his contemporaries.

“My greatest thrill in major-league baseball was the fact that I played in an era when the greatest major-league baseball players played, or ever will play again,” he said. “That, I will never forget.”39

Like most of his peers, Baumholtz worked in the offseason throughout his career. A connection in Chicago led to a job with the John Morrell Meat Company that kept Baumholtz busy in the winter the last few years of his career, and he transitioned to that work full-time after retiring from baseball. He worked for Morrell for years, and was elected president of the Associated Grocery Manufacturers’ Representatives of Cleveland in 196940 before moving on to Marquardt Brothers Inc. the following summer.41

In 1965 Baumholtz was inducted as one of eight inaugural members of the Ohio University Athletics Hall of Fame. He joined the university’s board of trustees in 1979 and served for 11 years, including a term as chairman. On February 4, 1995, Ohio U. retired Baumholtz’s number 54 basketball jersey, making him the first Bobcats athlete to have his number retired.42

Frank and Bettie had a son and two daughters, all of whom followed in their parents’ footsteps by graduating from Ohio U.

Bettie died of cancer on April 27, 1980, in Cleveland. Frank continued to live in Cleveland through the 1990s before moving to Florida to be near his daughters.

Frank Baumholtz died of complications from colon and liver cancer on December 14, 1997, at a nursing home in Winter Springs, Florida.43 He was 79.

Notes

1 The 1940 US Census lists both of Baumholtz’s parents as being born in Yugoslavia, which did not become a country until after World War I. Frank Sr.’s World War II draft registration card from 1942 lists his birthplace as Austria, indicating the family likely came from a German-speaking area of what is now Slovenia but was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the time of his birth.

2 Frank C. Baumholtz, interview by William J. Marshall. December 10, 1992, Baseball Commissioner Oral History Project, Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History, University of Kentucky Libraries. (Hereafter cited as Baumholtz interview).

3 Baumholtz interview.

4 Baumholtz interview.

5 Baumholtz interview.

6 Tim Cohane, “Ohio U. Defeat of Duquesne Scrambles Court Ratings,” New York World-Telegram, March 19, 1941.

7 Baumholtz interview

8 “Reds sign 2 Cleveland Boys Playing at Ohio U.,” Associated Press via Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 2, 1941.

9 Baumholtz interview

10 “Sailors Defeat Indiana Nine in First Game, 13-4,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 29, 1942.

11 “Two Great Lakes Stars Find Navy a Door to Big Leagues,” Associated Press via the Washington Post, July 4, 1942.

12 Ninth Naval District World War II War Diaries, 1941-1945, accessed via Fold3.com.

13 Navy Department Library, http://history.navy.mil/faqs/faq104-1.htm, accessed October 26, 2013.

14 http://navsource.org/archives/10/15/150633.htm, accessed November 8, 2013.

15 LCI Flotilla 21 War Diary, August 31, 1945, accessed via Fold3.com.

16 Baumholtz interview

17 Baumholtz interview.

18 “Six Ohioans Add Punch to Rebel Cage Squad,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 28, 1946.

19 Alex Zirin, “Baumholtz Nets 25 as Rebels Win,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 4, 1946.

20 Baumholtz interview.

21 “Rebels’ Baumholtz is Reds’ No. 1 Center Field Candidate,” Associated Press via Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 27, 1947

22 Baumholtz interview.

23 Jack Ledden, “$6,000 Holiday From Basketball for Frankie,” The Sporting News, February 4, 1948.

24 Baumholtz interview.

25 “Larry Jansen Pitch Puts Baumholtz on Sidelines,” The Sporting News, July 28, 1948.

26 Baumholtz interview.

27 John B. Old, “Biff-Bang Baumholtz Gets Okay from L.A.,” The Sporting News, May 31, 1950.

28 “Baumholtz’ Hitting Skein Ends at 33 Games in Row,” The Sporting News, June 7, 1950.

29 Ed Burns, “Rush Uncorks Victory, Frisch Smiles – Once,” The Sporting News, June 13, 1951.

30 Baumholtz interview.

31 Edgar Munzel, “Baumholtz Injury Fails to Trip Cubs,” The Sporting News, June 18, 1952.

32 Ibid.

33 Roger Birtwell, “Spahn Guarded by Chicago Police Following Threat,” The Sporting News, July 23, 1952.

34 “Musial Now Pitching – With Bat Rival Up,” The Sporting News, October 8, 1952.

35 Richard Dozer, “Sox Remember Baumholtz and His Bat,” Chicago Tribune, May 10, 1969.

36 Bob Logan, “Baumholtz Covered a Lot of Ground,” Chicago Tribune, July 7, 1986.

37 L. Robert Davids, “New Records for Pinch Hitters,” Baseball Research Journal, 1977.

38 Ibid.

39 Baumholtz interview.

40 “Grocer Group Elects Baumholtz,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, December 24, 1969.

41 “Baumholtz Joins Marquardt Bros.,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 10, 1970.

42 “Baumholtz, only Bobcat athlete with retired number, dies at 78,” Ohio University Today, Spring 1998.

43 Alana Baranick, “Frank C. Baumholtz, Played in National League,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, December 24, 1997.

Full Name

Frank Conrad Baumholtz

Born

October 7, 1918 at Midvale, OH (USA)

Died

December 14, 1997 at Winter Springs, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.