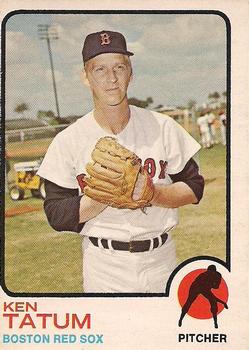

Ken Tatum

Right-handed reliever Ken Tatum was off to a brilliant start in his baseball career, a candidate for American League Rookie of the Year honors with the California Angels in 1969. The award had never gone to a relief pitcher, but Tatum’s stats (7-2, with a 1.36 earned run average) helped give him a Wins Above Replacement (WAR) rating of 4.8. The winner was position player Lou Piniella, with a WAR of 2.1. Interestingly, another pitcher — Mike Nagy of the Boston Red Sox — had been second, with 3.0 thanks to his 12-2 (3.11 ERA) record. Tatum finished fourth.

Right-handed reliever Ken Tatum was off to a brilliant start in his baseball career, a candidate for American League Rookie of the Year honors with the California Angels in 1969. The award had never gone to a relief pitcher, but Tatum’s stats (7-2, with a 1.36 earned run average) helped give him a Wins Above Replacement (WAR) rating of 4.8. The winner was position player Lou Piniella, with a WAR of 2.1. Interestingly, another pitcher — Mike Nagy of the Boston Red Sox — had been second, with 3.0 thanks to his 12-2 (3.11 ERA) record. Tatum finished fourth.

As the Angels’ P.R. staff enthused over his performance in a late September press release, they used a phrase that, seen retrospectively, seems almost eerie. Tatum was said to have been “fracturing records as the bullpen ace of the California Angels.”1 As events transpired, one of Tatum’s pitches the following year struck Baltimore’s Paul Blair in the cheekbone and in the long run may have held back Tatum from pitching inside as effectively as he previously had. The year after that, he himself suffered a broken cheekbone in a freak accident during a pregame practice.

Kenneth Ray Tatum was born in Alexandria, Louisiana, on April 25, 1944. His father Ray was in the Army at the time. “I guess that’s where my dad was stationed,” Ken Tatum said in a July 2018 interview. “My dad’s name was just Ray Tatum. He didn’t have a middle initial or anything. My mother was from Hickory, Mississippi. One day they told me the story that the train was going through Hickory and my dad threw a letter off the train to where my mother lived. The railroad track was right behind the house. That’s how he corresponded with her a few times. I thought that was real unique.

“My real mother passed away when I was 2 years old. I’ve gone back to visit my mom’s grave a few times; she’s buried in Hickory. I was raised by my grandparents. I called my dad ‘Ray’ and I called my grandparents ‘Mom’ and ‘Dad.’” My grandparents lived in Birmingham, so I guess that’s where I was raised. They had five or six uncles and aunts where they lived and they more or less took care of me. That was just when I was younger. Like in the third grade, I was still in my grandparents’ — until my dad remarried. When he married, we moved to a place called Midfield, outside of Birmingham.”2 Ray Tatum worked as an accountant for a trucking firm. After Ray remarried, Ken was joined by two half-brothers.

Ken attended Midfield Elementary School, 15-20 miles southwest of Birmingham, then Jones Valley High School in Birmingham, where he played both baseball and basketball. Tatum grew to become 6-foot-2 and was listed during his major-league career at 205 pounds. He had kept busy throughout his youth and played Little League baseball, Pony League, Colt League, and American Legion ball.

With a baseball scholarship in hand, he graduated from Mississippi State University with a B.S. in Education and a 28-9 record as a pitcher for the varsity. He was All-Southeastern Conference in both 1965 and 1966, leading the conference in ERA in 1966 with a 10-2 record. Mississippi State won the conference title both years. He beat Auburn twice in the 1965 playoffs and beat Tennessee State twice in the 1966 playoffs. He was carried off the field by his teammates after winning the 1965 title but ranked his most satisfying experience as beating two universities from his home state (Auburn and Alabama) twice each in conference play.3

Needless to say, the young starter had attracted the interest of baseball scouts. In the June 1965 amateur draft, he was selected by the Milwaukee Braves in the 21st round. Dixie Walker was the scout at the time. Ken chose not to sign, and to complete his senior year instead. In the secondary draft of January 1966, he was selected by the Detroit Tigers in the sixth round, but again chose not to sign. The timing was better for the California Angels and scout Roy Lee “Red” Smith in the June 1966 secondary draft. Ken was taken in the second round and signed on June 28 with the Angels. On signing with Red Smith, Tatum says, “I didn’t know him personally. . . He just contacted me and we met.”

The Angels sent him to Davenport, Iowa, to pitch for the Single-A Midwest League’s Quad City Angels. In 30 innings over nine games, he was 1-2 (3.30).

Tatum’s first full season of professional baseball was in 1967, pitching 157 innings for the San Jose Bees in the Single-A California League. In 21 starts, he posted a record of 12-6 with a league-leading 2.12 ERA, 141 strikeouts and only 48 bases on balls. He had a 1.000 fielding percentage, handling 40 chances without an error.

Promoted to Double A in 1968, Tatum pitched for the El Paso Sun Kings (Texas League). El Paso won the pennant. Tatum was 11-7 (3.41), and in 1969 was promoted once more, this time to the Triple-A Pacific Coast League. Over the winter, he pitched in Puerto Rico.

Tatum started the 1969 season, going 3-0 for the Hawaii Islanders, though with a 4.50 ERA.

The Angels called him up in May and his major-league debut came on May 28, 1969. The Angels converted him to a reliever and over his six seasons in the big leagues, Tatum only started twice.

The Angels had gotten off to an 11-28 start under manager Bill Rigney and after the May 25 game, Rigney was replaced by Lefty Phillips. Pitcher Rick Clark was optioned to Hawaii and Tatum brought up.

It was Phillips who beckoned Tatum in from the Anaheim Stadium bullpen during the Wednesday night May 28 game against the Cleveland Indians. After the top of the sixth, Cleveland held a 4-0 lead and a pinch-hitter was put in for starter Tom Murphy. Bill Voss singled, another single followed, Jim Fregosi drove in one run, and Bubba Morton drove in two. The score was 4-3 and the Angels were back in the game. Tatum was handed the ball and struck out the first two batters he faced, then induced a fly ball to left field. He was replaced by a pinch-hitter in the bottom of the seventh. The Angels ultimately tied the game in the eighth, and won it in the ninth.

Tatum faced two batters on May 30 and three batters on May 31, retiring all five. He got the win on May 31. He pitched two innings on June 4, and was finally touched for his first hit, a single. He surrendered his first run in his fifth appearance, on May 8, then didn’t yield another run until his 19th appearance, on July 13.

The first time he gave up more than one run was during a lengthy 6 1/3-inning relief stint against the New York Yankees on July 27, but he only gave up two runs in a 5-4 Angels victory that gave Tatum a record of 3-0. By the end of July, he held that 3-0 record, with seven saves, and an ERA of 0.95. An early September relief outing saw a Los Angeles Times writer exclaim, “Ken Tatum is like the guy on the white horse in one of those old Saturday afternoon westerns…the guy who rides into an impossible situation and gets the job done.”4

It was a magical season. He finished with a record of 7-2 with 22 saves in 45 appearances, which ranked second in the league, and an earned run average of 1.36, best for any reliever in the American League. A relief pitcher’s ERA doesn’t reflect inherited runners, but a December 16, 1969, press note said that of the 47 baserunners Tatum inherited in 1969, only 11 scored. “He is the best relief pitcher in baseball,” said Phillips.5 Angels pitching coach Marv Grissom said, “That boy has amazing coolness and that is very important in relievers.”6

Despite his early success, Tatum had said in midseason that he still hoped to become a starter. Belying his relaxed demeanor on the field, he said, “Actually, I’m very nervous. I don’t know the hitters. All I can do is challenge them. I learn something new each time…It’s a dream come true, It was my goal as a little boy.” He said that he wanted to return to being a starter, “but I know that if I keep pitching the way I have, the start will come. Right now, it’s enough of a thrill just being here.”7 By season’s end, he’d changed his mind. “At first I wasn’t happy in the bullpen, but I came to like it…the challenge of it all.” Phillips chimed in, “I think Kenny realized that this was the place he had to be to pitch in the major leagues. It’s where his future is.”8

The Angels had been in last place when Phillips took over and Tatum had been called up. They finished third. Tatum had enjoyed two scoreless streaks of 24 (June 10-July 12) and 17 innings August 8-September 1).

He had also been pretty good with the bat, hitting for a .286 average with a pair of solo home runs in 24 plate appearances.

In spring training 1970, he downplayed mentions of him in the same breath as Hoyt Wilhelm and Ron Perranoski. “That is just a lot of baloney. I had one good year. Any player can have one good year…Look at my minor league record for three years before that…there’s nothing that would indicate that I would have the kind of year I had with the Angels.”9 Come back and see me in five years, he said.

He worried that the strain on his arm would cause problems. Though he worked for the Angels doing public relations work in the offseason that one year, he planned the following year to begin work on a Master’s degree. His expressed hope at the time was to coach college baseball.10 “When I was with Boston, I went to Northeastern University. I got a Master’s there and then I started working on my Doctor degree. I got halfway through that and just quit.” Tatum’s Master’s was in secondary school administration. It was a degree he put to work after baseball.

Tatum had married Rebecca Ann Wrenn in May 1964, and the couple soon had a young son. “We met in the fifth grade,” he said in 2018. “We’ve been married 54 years.” They later had one more son and a daughter.

Tatum’s 1970 season picked up just where 1969 had left off. He was just as good, if not better through April and May, allowing just three runs in his first 20 games. He was 2-1 with eight saves and an ERA of exactly 1.00 at the end of May.

But in the last game of May, on the 31st at home, the Angels had a 6-1 lead over Baltimore. Tatum had thrown two scoreless innings. In the top of the eighth, he hit Boog Powell in the wrist with one pitch and then hit Paul Blair with another. Blair was seriously injured. He had multiple fractures of his nose and eye socket. More than a week later, Blair was still worried that his vision had not come back into focus. He had a 30-minute operation. Tatum visited Blair in the hospital and assured him that the beaning was accidental.11

Los Angeles Herald-Examiner sportswriter Melvin Durslag wrote a strongly-worded piece, admitting that there was no proof Tatum had intentionally hit Blair (there was no reason during the game, and no history between the two that had emerged), but Durslag said, “Irrespective of the evidence in this particular case, it remains the depressing fact in baseball that guys still are throwing fast ones purposely in the direction of other people’s heads.”12

Blair returned after three weeks and went on to continue a successful career. But the shock of seeing what his pitch had done to the Baltimore outfielder may have inhibited Tatum’s ability to pitch inside effectively. In early 1974, he did admit that the Blair incident affected him for a while, but he believed it was behind him. 13

If so, it wasn’t immediate. His 1.00 ERA at the end of May became 1.57 at the end of June, then 2.72 as July closed, and 3.30 at the end of August. Tatum had also suffered from an inner ear infection. He improved a bit by the end of the season, finishing at 2.94. He was 7-4 with 17 saves. He had worked in 62 games. It was still a good second season.

The Angels may have sensed a problem that was perhaps more serious than evident. On October 11, just a week and a half after the season was over, they traded Ken Tatum to the Boston Red Sox. It was a “double Tatum/double Jarvis” trade, with the unrelated Jarvis Tatum and Doug Griffin joining Ken on his way to Boston. The Angels received Ray Jarvis, Jerry Moses, and slugger Tony Conigliaro, who had suffered his own serious injury in an August 1967 beaning.

Ken Tatum was the key to the trade. “We had to get bullpen help,” said GM Dick O’Connell. Tatum was meant to complement left-handed reliever Sparky Lyle.14

Tony C was, of course, a big star in Boston, and had a good year in 1970, playing alongside his brother Billy Conigliaro. O’Connell, however, offered the thought: “The boys are better off separated. I think it’s been a liability having them on the same club.”15

Fans in Boston were irate. Tatum was looking forward to pitching in Boston. After noting that, while Carl Yastrzemski had homered off him once, he’d never had a ball hit off him that struck the left-field wall. “It’s one town I like to pitch in.”16

There was one thing he wanted to learn in Boston, he said, and that was to throw a slider. His previous coaches had told him just to keep firing his fastball. Under Red Sox pitching coach Harvey Haddix, he hoped to get better instruction than he had had in the Angels system. “I’ve always been told to stop messing around with breaking pitches, and throw the ball hard — hard so nobody can see it. Which is all right, but you’d like to set up a hitter once in a while.”17 He acknowledged having difficulty for three weeks after beaning Blair, throwing “nothing but pitches straight overhand” — and getting clobbered until Phillips told him to go back to his natural three-quarters delivery.18

Tatum’s first game for the Red Sox did not go well. On April 8 in Cleveland, he came in to close the game, pitching the bottom of the ninth with Boston nursing a 2-1 lead that disappeared after a single, a hit-batsman, a successful sacrifice, another out, and a two-run game-winning single by Gomer Hodge. By the end of April, though, he had 11 appearances under his belt and, despite a record of 0-2, five saves and a 2.02 ERA. Over the course of the season, that ERA doubled to 4.19 and he had a 2-4 record with only nine saves. He was far from the bullpen savior that the Red Sox had hoped to acquire. The Red Sox gave him one start, on August 17, but he only lasted a third of an inning.

He certainly was not the same pitcher he had been. He’d suffered a major setback on May 23, when he was struck by a “soft liner” during batting practice in Baltimore. He was walking off the field when the ball hit him, fracturing his cheekbone in three places. The freak injury cost him a full month.19 Though the surgery was successful, he suffered terrible headaches for weeks.

In 1972, though struck in the ankle by another batted ball in spring training, Tatum got off to a good beginning, with a 2.20 ERA at the end of May. But a sciatic nerve condition in his left leg and lower back put him on the disabled list for almost all of June and deep into July.

It was an unfortunate year for the Red Sox, too. A labor dispute had caused the schedule to start a little late. The agreement was that each team would play out what remained on its schedule when the season began. The Red Sox played 155 games and were 85-70, but that left them a half-game behind the Tigers, who also lost 70 games but had one more game on their schedule and won it, edging the Red Sox and costing them a trip to the postseason. Tatum’s record was 0-3 with a 3.07 ERA, and just four saves while working only 29 1/3 innings. Had he been healthier and saved one more game (and all else remained equal), the Red Sox would have won.

Tatum spent the 1973 season in the minor leagues with the Pawtucket Red Sox, and not successfully. That the Red Sox were able to get waivers on him was a surprise. In early August, he expressed frustration: “If Boston doesn’t want me, I don’t want them. I can still pitch in the big leagues and I cannot see playing for an organization where I am not wanted. I heard a rumor that Texas wanted me as part of the Sonny Siebert trade, but they would not trade me. It seems like I’m not good enough for Boston, but too good to be traded to some other team.”20

If he had been frustrated with the Red Sox at the time, that feeling passed. He was among the Red Sox alumni invited to the 100th anniversary of Fenway Park in 2012. “I considered it an honor that they invited me. I really did. I appreciated them inviting me. For medical reasons, I couldn’t go. I’ve had colon cancer surgery. I’ve had open heart surgery. It was just a situation where I really couldn’t go. I’m OK now. Everything’s OK. I’m just a little bit slower.

“I’ve got a picture on my phone my son and his son took of Fenway. That’s the wallpaper on my phone. I enjoyed Boston.”

Tatum started 11 games for the Pawtucket Red Sox and relieved in 21. His ERA was the worst of his career at any level — 4.81, and his record was 8-12. He was called up to Boston in September and appeared in one game, working four innings and giving up four runs. On October 26, the Red Sox traded him and Reggie Smith to the St. Louis Cardinals for Bernie Carbo and Rick Wise.

More than 30 years later, Peter Gammons wrote of the effect he believed the Paul Blair beaning may have had on Tatum’s pitching career: “From May 31, 1970, until his major league career ended in 1974, Tatum had a 3.95 ERA and allowed 1.14 homer per nine innings. After he retired, he admitted he pitched with the fear ‘that I might kill someone. I could never pitch on the inside half of the plate again.’”21

Tatum never pitched for the Cardinals, due to a tight muscle in his right forearm in spring training that consigned him to the disabled list, but he did have one more shot in the big leagues when the Chicago White Sox sent Luis Alvarado to St. Louis and acquired Tatum on April 27, 1974. He and Rebecca Ann had just had their third child, Kimberly Ann.

He appeared in nine scattered games for the White Sox in May and June, with a final 10th game on July 1. Working with pitching coach Johnny Sain, he said — clarifying that he did not mean to say anything against Sain, “Everybody that went there, he wanted to teach them how to throw the slider. I think I lost a little bit on my velocity. That may have contributed to what was going on.” His time in Chicago was his last work in the big leagues. He had a 4.79 ERA in 20 2/3 innings, with neither a win nor a loss.

The record shows him sent to the minors and pitching for the Iowa Oaks, where he was 0-2 in eight games, with a 6.92 ERA. He remembers otherwise.22 He was released in September.23

In 1975, though, he gave it one more shot, pitching for the Monterrey Sultanes in the Mexican League. One brief note in The Sporting News reported he had thrown five complete games by late April but had bad luck, with a record of 3-4.24 He didn’t play out the season. “I just got kind of fed up with that. I just quit on the spur of the moment. I was tired. I called my wife and told her to pick me up at Logan Airport there in Boston, and that was it.”

Asked about his last couple years in baseball, Tatum said, “Baseball’s political, like everything else. I loved playing in Boston. People were great. That’s where I bought my first house, in Foxboro. I got traded to St. Louis and that never worked out. I was put on the disabled list in St. Louis and then I was traded to the White Sox. That’s when Chuck Tanner was manager. I don’t know what happened in Chicago. I was pitching so-so there, and then I was sent down to Des Moines. We were ready to go on a road trip to Houston, I think it was on July 4, and while I was at the ballpark they told me I was being sent down. You have to get all your luggage off the bus. When I was sent down to Des Moines, I never pitched again in a ballgame. When I was sent down to Triple A, I never pitched in a game.”

After baseball, Tatum says, “I was in school administration for 18 years. I was an assistant principal and a principal. In Shelby County, about 10 miles outside of Birmingham. That’s where I live now. I’ve been an administrator of a day care for 20-some years now. That’s where I still am. It’s local day care, privately owned. I like it. It keeps me active.” The day care center is in West End, Jefferson County, Alabama, and cares for about 100 children, age six weeks to 12 years.

Ken and Rebecca’s son Kenneth Ray Tatum Jr. served in the United States Air Force and retired as a colonel. “He flew the F-117 stealth bomber and the B-1 bomber. He did pretty well. I think you could pull him up on the internet. My other son, Kevin, he’s a school administrator. My daughter Kimberly has been a housewife. I’ve got seven grandchildren.” And he’s got that photo of Fenway Park as the wallpaper on his phone.

Last revised: August 1, 2018

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Tatum’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee.

Notes

1 Undated press release from the California Angels found in Tatum’s Hall of Fame player file. The date was almost certainly September 24 or 25, 1969, based on its reference to citing his stats through September 23, and looking forward to the Angels beginning their final road trip on September 25.

2 Author interview with Ken Tatum on July 3, 2018. Unless otherwise indicated, all direct quotations attributed to Ken Tatum come from this interview.

3 Career summary produced for the 1970 season. Ken Tatum player file.

4 John Wiebusch, “Tatum Again Rides To Rescue; Angels Blank Chisox, 1-0,” Los Angeles Times, September 5, 1969: 11.

5 John Wiebusch, “No. 1 Relief Pitcher? ‘Tatum!’ Angels Say,” The Sporting News, October 11, 1969: 14.

6 Ibid.

7 Ross Newhan, “Tatum Sleeps A Lot — But Not on Hill,” The Sporting News, July 12, 1969: 19.

8 John Wiebusch, “Tatum Angels’ Bullpen King,” The Sporting News, November 15, 1969: 48.

9 John Wiebusch, “Tatum, Sailing on Cloud 9, Hopes Bubble Doesn’t Burst,” The Sporting News, April 11, 1970: 46.

10 Ibid.

11 “Blair, Orioles Must Wait to Learn If Injury Will Affect His Eyesight,” The Sporting News, June 13, 1970: 17.

12 Melvin Durslag, “Danger in Dusters,” The Sporting News, June 20, 1970: 10.

13 Neal Russo, “Tatum Aims to Put Reddish Tint on Bosox Faces,” The Sporting News, January 12, 1974: 31.

14 Larry Claflin, “Red Sox Give Up Power for Strength in Bullpen,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1970: 13.

15 Clif Keane, “Sox Ship Tony C to Angels in 6-player Deal,” Boston Globe, October 12, 1970: 78.

16 Kevin Walsh, “Fenway Wall Never Worried Ken Tatum,” Boston Globe, October 13, 1970: 25.

17 Clif Keane, “Tatum Fires Fastballs But Dreams of Sliders,” Boston Globe, January 24, 1971: 86.

18 Ibid.

19 Clif Keane, “Tatum’s Cheekbone Fractured,” Boston Globe, May 24, 1971: 19.

20 “Struggle for Tatum,” The Sporting News, August 11, 1973: 38.

21 Peter Gammons, “Gold Glove outfielder Paul Blair passes away at 69,” Gammons Daily, December 27, 2013. http://www.gammonsdaily.com/peter-gammons-gold-glove-outfielder-paul-blair-passes-away-at-69/ Accessed June 30, 2018.

22 Roberto Hernandez, “Mexican Loop Turnstiles Click Like Castanets,” The Sporting News, April 19,1975: 24. The statistics from the Iowa Oaks come from Baseball-Reference.com at https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=tatum-001ken (accessed July 4, 2018) and differ from Tatum’s own clear recollection that he never pitched at all for the Oaks. Asked about this during the July 2018 interview, he said, “I don’t know how I was 0-and-2, because I never pitched in a game.”

23 Hernandez.

24 “Tatum Lasts Route,” The Sporting News, May 3, 1975: 30.

Full Name

Kenneth Ray Tatum

Born

April 25, 1944 at Alexandria, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.