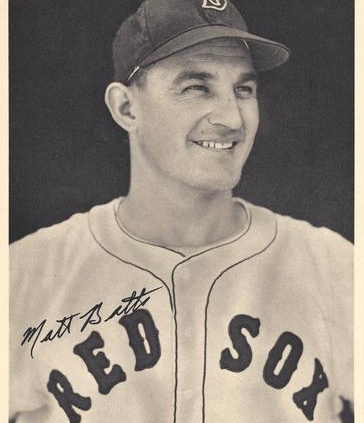

Matt Batts

Ten years a backup catcher for five major league teams, Matt Batts was born and raised in San Antonio, Texas. He lived in the north part of the city at the time, but San Antonio has grown so much since he was born on October 16, 1921, that where he lived would be nearer the middle of the city today. His earliest baseball memory is of playing on the gravel streets of the city. “I was always the one that hit the furthest and all of that.”

Ten years a backup catcher for five major league teams, Matt Batts was born and raised in San Antonio, Texas. He lived in the north part of the city at the time, but San Antonio has grown so much since he was born on October 16, 1921, that where he lived would be nearer the middle of the city today. His earliest baseball memory is of playing on the gravel streets of the city. “I was always the one that hit the furthest and all of that.”

Matt’s father Matthew was a fireman. His mother Margaret died when he was about a year old. Keeping it in the family, Matt’s father married one of his mother’s sisters, Brettie. Matt had no brothers or sisters, though a half-sister Eva came from the union of Matt Sr. and Brettie. She lives in San Antonio today.

From the sandlots, Matt progressed through the city’s schools. ”I played when I was at junior high school, I was quite a hitter. I was pretty good size, you know. Everybody that had a ball club wanted me to play. I would have my bicycle and I’d ride my bicycle across town, or any place to play baseball.” The year he started high school, though, the city discontinued its baseball program due to its expense. Unable to play high school ball, he played American Legion ball and in a few other leagues nearby. He was named to the All-State team in Texas for his Legion ball play. ”I played with a semipro team that played around San Antonio, out in the sticks. They would pay you a few bucks, five dollars or something, you know. One of the fellows that used to play with Chicago, Art Veltman, lived there in San Antonio. He is the one that got the team together.” The teams played around the city, not even traveling to nearby San Marcos, but Batts remembers one road trip when a local sportswriter arranged for a truck loaded with hay in the back and drove the team to Del Rio to play a team on the border.

He started catching in semipro ball, pretty much by accident, really the result of a little clowning around. “We were beating a team pretty bad and we started changing up, you know, different positions, and I told the catcher I wanted to catch, I wanted to see how it was catching. I picked off a runner at first and threw one out at third. I had always had a great arm. I could throw one from home plate over the left field fence.” It’s something he never tried at Fenway Park.

He still holds the high school javelin record for the state of Texas. Batts enrolled at Baylor and played on the freshman baseball team — which was good enough to beat the varsity. He left after about a year and a half. “They about run me off,” he laughs. “One of the reasons I quit at Baylor was because I had signed a major league contract and didn’t tell them about it. I didn’t realize at the time that it was against the rules and regulations. I had a deal with the Boston Red Sox that they would pay my way to school and I could still play football and baseball.”

Indeed, he had been offered a $2,500 bonus and a new car — quite large at the time — by Red Sox scout Uncle Billy Disch, the University of Texas coach. Veltman, who was a Tigers coach and had wanted to sign Matt, was upset to learn he’d left school and had been beaten out. “He was a great, great, great coach. He was one of the better coaches in the country. He had been after me for some time.” Batts signed in 1942 and was sent to Class-C Canton (Ohio) of the Middle Atlantic League. Batts caught 95 games, batting .294 in 483 at-bats, with 10 home runs and 82 RBIs.

The country was at war, and ballplayers were no more exempt than anyone else. “Mel Parnell was there at Canton with me. He was pitching and we were both friends, because he lived in New Orleans and I lived in San Antonio. It was pretty close, you know. Not too far away. We roomed together there in Canton. We became great friends. When we got back home, some boys that I knew real well that had played ball with me there in San Antonio had entered the service at Randolph Field. One of the colonels over there got them to come and get hold of me and see if I wouldn’t sign up instead of just getting drug into anything. With them being there, I said I’d go ahead and join the service.”

Matt enlisted in the Army Air Corps at Randolph Field. He became a crew chief, servicing aircraft, mostly trainer planes for the cadets coming through as prospective pilots. His job was to ensure that everything was in shape with the aircraft, ready to go each morning. He served at Randolph Field for the duration of the war, reaching the rank of sergeant. After he was discharged, the Red Sox sent him to nearby Lynn, Massachusetts, to play in the Class-B New England League in 1946. Despite having lost three years to military service, he improved his production at the higher level of play: he hit .337, drove in 86 runs, and hit 12 homers.

In 1947, he was promoted to Scranton in the Single-A Eastern League but appeared in only eight games there. He’d won the job over the first-string catcher, hitting a grand slam in the ninth inning to win one game — but then didn’t get to catch another game. “You know how politics are in baseball,” he says. ”I sat on the bench, and they let some catcher catch that had been there the year before. About two or three weeks passed, so I got hold of the manager [Eddie Popowski] and told him, ’Look, I want to play ball. I don’t give a damn where it is.’ I wanted to play. He said, well, he couldn’t do anything about it. They wanted this boy to catch and I got to let him catch. So he caught.”

As it happened, the catcher for the Red Sox International League affiliate in Toronto, Gene Desautels, got hurt. The club asked Boston for a replacement and was sent Matt Batts. When Desautels got better, the manager put him back in, but the team’s owner laid it on the line: “You get Batts to catching or you’re gone.” Matt told the manager, Elmer Yoter, that he had no idea why, that he’d never met the owner. It wasn’t the only time Toronto’s owner helped out the 24-year-old catcher. “When I was on one of the road trips, my old Chevrolet caught fire and my wife was all scared to death, called me about it. Some people got it put out for her. The owner took my car and had the durn thing all fixed and everything, and paid for it and never charged me a nickel for it.” As to the owner, Peter Campbell, Matt says even today, ”I never have met him.” Matt’s wife Arlene notes that they were so poor at the time they could hardly afford a gallon of gasoline.

Late in the season, when Toronto’s season was over (Batts hit .262, with seven homers and 40 RBIs), both he and pitcher Cot Deal were summoned to play with the Red Sox. Batts struck out in his first at-bat, pinch-hitting for Harry Dorish on September 10. The following day, he started both games of the doubleheader against the Indians. He was 2-for-4 in the first game with a double and a home run, and 3-for-3 in the second game, all singles. He made a bit of a splash, hitting .500 in 16 at-bats for manager Joe Cronin.

Batts was the backup catcher for Birdie Tebbetts in 1948 and did quite well, hitting .314 in his 118 at-bats. From the time he hit the big leagues, Batts never played anywhere other than behind the plate. He felt he saw an improvement on the team under new manager Joe McCarthy, he told Peter Golenbock in the book Red Sox Nation: “Coming back in ’48, it was more organized than the year before….The difference, in my opinion, was Joe McCarthy. He was super. Oh, yeah. He didn’t say much, but you just felt great with the man there. You had the feeling that you had to play your best at all times. Not that he was forcing you. It was just that you had that good feeling.”

As Birdie’s backup — and roommate for three seasons — had McCarthy consulted either him or Tebbetts before selecting Denny Galehouse as the playoff starter in 1948? He had not, and Batts says that McCarthy never said why he decided on Galehouse. The veteran pitcher had done very well against the Indians in an earlier relief stint, and McCarthy thought the other pitchers were, in Batts’ words, “kind of wore out.” It didn’t work out, but McCarthy was “a great manager. No doubt about it. He was the best that I ever was with.”

Batts really enjoyed the 1948 team and enthused about it to Golenbock: “When you woke up in the morning, you wanted to get to the ballpark to play ball, because you enjoyed it, and you loved the people you were with, loved the manager, loved the coaches, and of course, we had great ballplayers.” He did admit, though, the team was “upset” about McCarthy naming Galehouse: “The whole 25 ballplayers. I don’t think there was one of them that wasn’t upset…. We lost some respect for McCarthy, everybody got kind of down on him because of it.”[fn]Golenbock, Peter. Red Sox Nation, pp. 176-77[/fn]

In 1949, Batts got in more games, but didn’t hit as well (.242 in 157 at-bats.) “I just had to wait my turn,” he says. “The more someone can play, and get up to the plate, and hit every day, every day, every day he can hit better that day, rather than play one day and five or six games later, play another. You’re just hitting and missing. You’re not going to be a good hitter doing that.”

In 1950, Matt got even more work, and improved to .273, but when manager Steve O’Neill came in to take over from McCarthy, it became less enjoyable. “Steve O’Neill didn’t like me for some reason. I thought I was a friend of his, because I knew one of his sons and one of his daughters, you know. Through baseball. When they got him over there, I figured, well, everything’s going to be all right.” It was not. And early in 1951, he was traded to the St. Louis Browns in a complicated deal that saw the Red Sox acquire Les Moss, while sending the Browns $100,000, Batts, Jim Suchecki, and a player to be named later, who proved to be Jim McDonald. It was, Batts remembers, originally meant to be a three-way deal. St. Louis was supposed to trade him on to Detroit, but that didn’t happen until the following February.

He had hoped to get more playing time with St. Louis, but was blocked there by Sherm Lollar. He is blunt about playing for the Browns: ”That was the worst place I ever wanted to play.” He admits, though, that he did well, hitting .302 with St. Louis in 1951. And he had a number of experiences to look back on later — catching Satchel Paige among them. Bill Veeck was the owner and Batts was there for the Eddie Gaedel game.

After arriving in Detroit, Batts served as backup to Joe Ginsberg in 1952, struggling with a disappointing .237 average and a paltry 13 RBIs. When Ginsberg was sent to the Indians in an eight-player trade in June 1953, Batts took over as first-string catcher, and boosted his average to .278, hitting six homers and driving in 42 runs in 374 at-bats, the most he ever had in major league ball. On the flip side, he suffered the misfortune of being the catcher in the June 17, 1953 game when the Red Sox scored 17 runs in one inning. But back on August 25, 1952 he’d enjoyed being the backstop for Virgil Trucks’ second no-hitter of the season.

He missed a lot of time in 1954. He came down ill and was diagnosed as having hemorrhaging ulcers. Never having had stomach trouble of any sort, it was a mystery. “I never had had a stomach ache. I don’t know what it was. I know I bled like a stuffed hog, I know that.” After two days in the hospital, with the Tigers visiting Boston, Batts determined to check himself out. Told he couldn’t leave, he simply absented himself. “I went out the back door, caught me a train and went to Boston, and that’s where they found out that I had lost over 70 percent of my blood and they rushed me to a hospital, to the doctor, and I stayed there 30 days in bed. I had to eat baby food for gosh knows how long. About a year.”

Batts was traded to the White Sox at the end of May, then traded in early December to Baltimore which in turn sold him to Indianapolis in April 1955, before the season began. “I was going to Baltimore with Paul Richards to be his catcher. One practice in spring training, Richards come up with the idea of pitching the ball underhanded in the rundowns, between first and second, second and third, third and home. Well, old dumb-butted me, when the play got to Pesky and I, Richards asked Pesky, ‘How do you like that, Pesk?’ And of course, Pesky was smarter than I was. He said, ‘Oh yes, that’s all right.’ He said, ‘Batts, how’s that with you? Is that all right with you?’ I said, ‘No, I don’t know. They’ve been throwing the ball overhanded for 150 years. Someone’s going to get stung on this game.’ Next day, I was gone.” The Orioles sold him to Indianapolis on April 12.

Even with Indianapolis, he hit only .231, though when he got a shot with the Reds in early July when Hobie Landrith was placed on the DL and Cincinnati purchased his contract, he posted a .254 average. His career pretty much just petered out. He spent most of 1956 in the Southern Association playing for Nashville (other than three plate appearances for Cincinnati), hitting .258. He split time in 1957 between Birmingham and — back where it all began on the gravel streets — San Antonio.

“I just finally retired. I didn’t want to bum around in the minor leagues. I was getting up in age. Being sick like I had been, I didn’t feel like doing too much. I had been going to spring training all these years, and stopping over in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and helping the boys in the kids baseball clinic here. I didn’t have a job in San Antonio or anything.”

He and his wife, Arlene, have two daughters. One of them married the brother of longtime Boston sportswriter Larry Claflin. The family moved to the Louisiana state capital, Baton Rouge. Matt became friends with the sheriff, who initiated a program for juveniles — “instead of the regular deputies arresting juveniles, we would go out and pick them up and talk to them and see if we couldn’t get things straightened out.” He worked in the district attorney’s office, while his wife ran Batts Printing, a business he’d begun with an attorney friend. “We had to buy another press, and then another one. Business got to be so good that I quit the DA’s office and went in to help her, and we made it into quite of a great business. We sold it a few years ago and we just retired. We moved out here to the Country Club of Louisiana. Nicklaus built the course out here, and made it a nice subdivision. It’s all gated and everything, and I do nothing but play golf.”

Matt Batts died at home in Baton Rouge, of natural causes on July 14, 2013. His daughter Denise Claflin said his dedication to baseball was life-long. “When he was 90, he taught my daughter how to throw a baseball because she wasn’t throwing the ball right to the dog. He still threw it to exactly where he wanted.”[fn]Jennifer A. Luna, “Major league catcher Batts loved the game,” San Antonio Express-News, July 17, 2013.[/fn]

Author’s note

This biography originally appeared in the book Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948, edited by Bill Nowlin and published by Rounder Books in 2008.

Sources

Interviews done by Bill Nowlin on March 5, 2006 and April 26, 2007.

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Matthew Daniel Batts

Born

October 16, 1921 at San Antonio, TX (USA)

Died

July 14, 2013 at Baton Rouge, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.