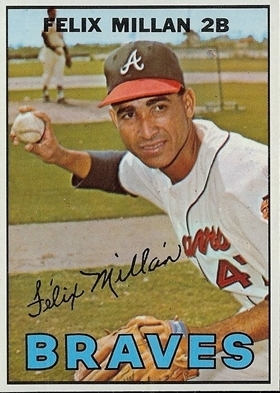

Felix Millan

Baseball fans in the 1960s and ’70s could bet their Cracker Jack that second baseman Félix Bernardo Millán would put the ball in play when he stepped up to bat for the Atlanta Braves or New York Mets. In 6,325 plate appearances, the 172-pound right-handed batter whiffed only 242 times, establishing himself as the National League’s toughest hitter to strike out in four of his 12 major-league seasons.1 Fans also remember the funny way Millán held his bat, choking up so high it looked as if he’d punch himself in the stomach when he swung at a pitch. He obviously did not choke the bat to produce home runs because he hit only 22 in his major-league career. He choked the bat to get hits and move up runners. In 1,480 games, he had 1,617 hits and a batting average of .279. Today some still consider Millán the best second baseman to ever play for the Braves and among the best to play for the Mets.2

Baseball fans in the 1960s and ’70s could bet their Cracker Jack that second baseman Félix Bernardo Millán would put the ball in play when he stepped up to bat for the Atlanta Braves or New York Mets. In 6,325 plate appearances, the 172-pound right-handed batter whiffed only 242 times, establishing himself as the National League’s toughest hitter to strike out in four of his 12 major-league seasons.1 Fans also remember the funny way Millán held his bat, choking up so high it looked as if he’d punch himself in the stomach when he swung at a pitch. He obviously did not choke the bat to produce home runs because he hit only 22 in his major-league career. He choked the bat to get hits and move up runners. In 1,480 games, he had 1,617 hits and a batting average of .279. Today some still consider Millán the best second baseman to ever play for the Braves and among the best to play for the Mets.2

Millán’s story begins in the barrio of El Cerro del Calvario, in Puerto Rico, where he was born on August 21, 1943. An aunt started calling him “Nacho,” mistakenly thinking it was the nickname for Bernardo, his middle name. By the time she learned it was short for Ignacio, Felix was already answering to Nacho, the name his family and friends from Yabucoa continued to call him. Millán was one of those kids who grew up in the sugarcane fields of the Caribbean batting a ball of string with a guava branch and dreaming of someday making it to the big leagues. “I prayed to God that I could make enough money to help my parents,” he said in a 2010 interview.3

Millán was the third of 11 children born to Victor and Anastasia Millán of Yabucoa, Puerto Rico. One baby died at birth and another died at a very young age, leaving a family of nine children. Victor Millán worked at a sugarcane-processing plant during harvest season, earning about 35 cents an hour, while Anastasia took in laundry to help meet expenses. Often, however, there was not enough money to buy food for the large Millán family. To make a little spending money, young Félix found odd jobs such as shining shoes or picking a grass called coitre, which he sold for ten cents a bag to people who raised rabbits.

An extremely shy kid, Félix was painfully embarrassed that he had no shoes to wear to school. To hide his bare feet from the other students he would stretch them as far under his seat as possible, living in constant fear of his teacher calling him to the front of the classroom. When he was 10 years old, his father sent him to live with his grandparents in the rural barrio of Juan Martín, where among other chores he took care of an uncle’s fighting cocks. Living in the country meant the young boy walked almost an hour to and from school every day, giving him a lot of time alone in his own thoughts, usually dreaming of baseball and his hero Lou Gehrig. A baseball field was the one place his shyness disappeared.

In grade school Félix played in a league sponsored by the Yabucoa police department. For lack of high-school baseball in Puerto Rico, during his teen years he played on a local amateur team, where his agility and quick glove soon made him one of the most popular kids in school. Everyone wanted Nacho on their team. After graduating from high school in 1960, with no plans for his future and no money for college, he joined the US Army. He hated Army life, however. Away from Spanish-speaking Puerto Rico for the first time, he was lonesome and homesick. Things finally began to look up for Millán when he discovered that Army bases had baseball teams. After he made the team, Army life was not so bad for Félix. Letters from a young woman in Puerto Rico also helped. Sensing correctly that Félix missed his home land, a friend suggested that he write to a girl named Mercedes “Mercy” Garcia. In time the two were exchanging letters three or four times a week and were looking forward to his discharge in July 1962. Millán may have been anxious to meet Mercy, but her father was not so sure about him. Without their knowledge, he went to Félix’s hometown to personally investigate Mercy’s young suitor. There he discovered that everybody in Yabucoa knew Nacho Millán, the shy kid who dazzled hometown fans on the baseball field. Mercy’s father not only allowed her to continue seeing Félix, he also said yes when the young man asked for permission to marry her. Félix and Mercy were married on December 21, 1962, two kids madly in love and sharing a dream of a career in professional baseball.

Baseball scout Félix Delgado spotted Millán playing first base in Puerto Rico’s Double A4 professional league and signed him for the Kansas City Athletics in 1964. Although Delgado soon switched him to second base, Millán started out playing first base with the Daytona Beach Islanders of the Class A Florida State League. After a year in the Athletics system, the Milwaukee Braves drafted Millán on November 30, 1964, and signed him for only $2,500. He was assigned to their Yakima (Washington) team in the Class A Northwest League, where he met manager Hub Kittle. Millán remembered that at one point when he was batting under .200, Kittle personally took him aside and practiced with him every day until he was hitting over .300. He also credited Kittle for advising him to choke up on the bat.5 Millán moved up the Braves’ minor-league ladder quickly, playing in 35 games for Austin of the Double-A Texas League at the end of the 1965 season.

Millán joined the Braves in the spring of 1966, the club’s first season in Atlanta after moving from Milwaukee. What he remembered most about his first day in Atlanta was meeting his future roommate, Hank Aaron. Approaching the new kid on the team, Aaron invited Millán to stay in his home rather than a hotel his first night in Atlanta. The next morning Aaron handed him a set of car keys. “Take my Camaro,” Hank said. Not only did Aaron loan Millán his car, he asked to room with the Puerto Rican when they played on the road. The two were roommates throughout Millán’s years with the Braves.

Millán, the 27th player from Puerto Rico to make it to the big leagues,6 made his major-league debut on June 2, 1966, getting a single in his first at-bat off Bob Bolin of the San Francisco Giants. Manager Bobby Bragan had benched the struggling veteran second baseman Frank Bolling in favor of Millán, and Félix did not disappoint his skipper. Millán started 21 straight contests and had his first major-league four-hit game on June 7 at Shea Stadium in New York. However, a broken finger sidelined Millán in late June, and he then found it hard to return to the regular lineup with Bolling and Woody Woodward handling the position.

Millán knew something was amiss when new manager Billy Hitchcock invited him to breakfast after only 87 days in Atlanta and only three days shy of receiving a much-anticipated progression bonus. His heart sank as he listened to Hitchcock explain that he’d rather see him playing in the minors in Richmond than sitting on the bench in Atlanta. Brokenhearted, Félix knew better than to argue the point. Sitting across the breakfast table from Hitchcock, he listened politely and kept his mouth shut, not daring to say anything that might jeopardize his future in the big leagues. Millán did his job at Triple-A Richmond, hitting .306 for the remainder of the International League season.

As the 1967 season started, Millán was back with Atlanta, but struggled at the plate and, sporting a paltry .194 average, was sent down at the end of May. Back in Richmond, he teamed up with third baseman Bobby Cox and, as Laurence Leonard reported, the pair created a lot of interest in minor-league baseball, drawing huge crowds and leading their team to the International League pennant in 1967.7 With a .310 batting average, he won the minor-league Player of the Year award.8 The best thing that happened to Millán in Richmond was manager Lum Harris. Probably nobody in his baseball career believed in Millán more than Harris, who later claimed the Puerto Rican to be the best second baseman in the National League.9

Millán was recalled in early September, and raised his batting average to .235. Atlanta was floundering badly in seventh place near season’s end and fired Hitchcock with three games remaining in 1967. Harris was named manager for the 1968 campaign a week later and took Félix with him. Soon the second baseman was getting a fair amount of attention by the press. “He can hit, he can hit and run, bunt for a hit, sacrifice and finagle a base on balls. He can run and slide and he can scramble back up and run some more,” wrote Gary Ronberg.10

It was those skills that earned Millán the nickname Kitten or Kit for short. In his homeland they called him “El Gatito.” The English moniker evolved to Cat, which stuck for the rest of his career. Félix “Cat” Millán had a way of playing the game without attracting a lot of attention. As Lum Harris told Ronberg, “He’s the type of player that you never realize is around until the game is over. Then you look up and he’s got two hits, an RBI, stolen base, and he’s been in on two double plays.”11 During his first full season in the majors, Millán was batting .309 at midseason before finishing at .289, just missing the Top 10 in the league, during the “Year of the Pitcher.”

From 1969 to 1971, Félix was named to three straight All-Star teams, playing in two of the midsummer classics (1969 and 1971). He also won Gold Gloves in the same years his children (a son, Bernardo, in 1969 and daughter, Femerlie, in 1972) were born. Millán was the first Brave to play in all 162 games of a regular season (1969), the same year he achieved career highs in RBIs (57) and home runs (6). Defensively, during the 1969 season he led National League second basemen with a .980 fielding average, 373 putouts, and 444 assists.

Never hailed as a home-run hitter, Millán hit his only major-league grand slam on April 8, 1969, against San Francisco Giants pitcher Gaylord Perry. That year he helped the Braves take the top spot in the National League West and go to the first-ever National League Championship Series. Although the Braves were favored to win the series, New York’s Miracle Mets surprisingly won the pennant with a three-game sweep of the then best-of-five playoff. Millán hit .333 in the series. During the 1969 NLCS, Wayne Lockwood of the San Diego Union observed, “Millán does his job with a quiet competence in all departments that inspires respect from both sides of the diamond.” 12

In 1970 Félix batted a career-high .310 and scored 100 runs, also a career high. He became the first Brave to go 6-for-6 in a nine-inning game, a team record he held by himself for 37 years until Willie Harris tied it in 2007. The Braves second baseman completed a career high 120 double plays in 1971, had 8 triples, and struck out only 22 times in 577 at-bats, making him the National League’s toughest batter to strike out for the first time.

Even though he won his second Gold Glove the following year, 1972, Millán played in only 125 games because of an injury, and his batting average slipped to .257. At the end of the season, the Braves chose to trade him for some much-needed pitching talent. Millán was not surprised by the Braves’ decision to trade him, and he was elated when he learned where he was going. Manager Eddie Mathews tried to break the news carefully because he knew Félix was loyal to the Braves. As Millán told the story, Mathews apologized as he broke the news that he was going to the Mets. “What’s there to be sorry for?” Félix thought. “Does he know how many Puerto Ricans live in New York?”

Millán was traded, along with pitcher George Stone, for pitchers Gary Gentry and Danny Frisella in what is considered to be one of the best trades the Mets ever made.13 For Millán, from his first day with the club he felt as if he had been with them forever. While the Mets’ 1973 season looked like another in a string of disappointing years after their 1969 world championship, Millán was having the best year of his career. His 16 hits and a batting average of .533 earned him the National League Player of the Week award on June 17. Millán was a key player in the Mets’ remarkable turnaround in the last five weeks of the season. Winning 24 of their last 33 games, they managed to get 82 wins to squeak into the top spot of the NL East. By the end of the season Félix had regained his standing as the toughest man to strike out with only 22 strikeouts in a Mets season record of 638 at-bats. He also led the Mets in games played (153), runs (82), hits (185, a Mets season record), singles (155), triples (4), batting average (.290), hit by pitches (6), sacrifice hits (18, a Mets season record). His .989 fielding average in 1973 was his career high and the third best in the league that season.

New York sportswriters named Millán the team’s Most Valuable Player. Beating the odds by taking the National League pennant three games to two during the best-of-five playoff over heavily favored Cincinnati, the Mets did what naysayers said could not be done and were on their way to the World Series again. But the 1973 Series against the Oakland Athletics was plagued with bad hitting and errors,14 and the Mets’ sure-handed second baseman was no exception. One of the key players responsible for getting the Mets to the World Series made what was probably the most embarrassing error of his career when he misjudged a groundball by Bert Campaneris, allowing it to pass under his glove for a crucial error during the third inning of Game One which led to both Oakland runs in a 2-1 loss for the Mets.

The Series went seven games before Oakland finally won it, with Millán batting just .188. After the World Series, Millán went home to Puerto Rico for what turned out to be the best of the 17 years he played winter ball with the Caguas Criollos. The team took the Puerto Rican League title for the first time since 1968 and went on to win the 1974 Caribbean Series, a feat it had not achieved in 20 years.

Back in the States, Millán continued to be the National League’s toughest batter to strike out in 1974 and again in 1975, achieving that distinction four times in five seasons. In 1974 he broke his own record and led the National League with 24 sacrifice hits, and also led the Mets for the season in singles (121) and hit by pitches (8). Playing 162 games in 1975, he became the first Met to play every game in a regular season (a mark tied by John Olerud in 1999), thus repeating his 1969 achievement with the Braves. He also established Mets season records (all of which have since been broken) with career highs of 676 at-bats, 191 hits, and 37 doubles.

In his Mets career, Millán played nine games in which he had four or more hits. The most famous of these games included a dubious achievement on the part of teammate Joe Torre. Félix batted ahead of him on July 21, 1975, in a game against Houston. Millán hit four singles, which Torre followed with four grounders to give the Astros four easy double plays. Torre set a National League record, hitting into four double plays in a single game, and afterward credited Félix for the “assists.” “I’d like to thank Félix Millán for making all of this possible,” Torre said.15

Millán continued to be the Mets’ leader in several categories in 1976: 139 games, with 531 at-bats, 150 hits, 122 singles, and 7 hit by pitches. He tied for the team lead with 25 doubles and, among players with 500 at-bats, led the team with a .282 batting average. But Millán’s major-league career literally came crashing to the ground on August 12, 1977, at Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium. He had just entered the games as a defensive replacement in the sixth inning during the second game of a doubleheader against the Pirates, and the Mets’ quiet, well-respected second baseman lost his cool in an on-field brawl when Ed Ott tried to break up a double-play attempt. The Pirates had runners on first and second when Mario Mendoza hit a grounder to shortstop Doug Flynn, who flipped the ball to Millán to try for a double play. All of a sudden Millán was on the ground with his face in the dirt, knocked down by Ott, who slammed into him like an NFL linebacker. Millán came up spitting and shouting and, with the ball still in his fist, punched Ott in the face. Millán said he fully expected a return punch. Instead, Ott picked him up and body-slammed him to the ground. The benches cleared, Ott was ejected by home-plate umpire Ed Sudol, and Millán was carried out on a stretcher with a broken clavicle, dislocated shoulder, and severely wounded pride. Ott was later fined $250 by National League President Chub Feeney.

When an offer came for Millán to play in Japan, he was ready to move. He played three seasons (1978-1980) with the Yokohama Taiyo Whales (now the Yokohama BayStars). In 1979 he helped them achieve their best season to date, finishing in second place in the Central Japan League. With a .346 hitting record in 1979, Millán was the first foreigner to claim Japan’s batting title, and he received the Best Nine Award.16

Millán loved playing in Japan, and was well liked there. His quiet demeanor and dedication to the game helped him fit into the culture of Japanese baseball, where players are expected to put their team’s interests ahead of their own.17 However, Félix made a little known and highly unusual request of his managers in his last year with the Whales when he asked to be excused from Friday night and Saturday games for religious reasons. He wished to join his wife, a Seventh-day Adventist, in observing the Sabbath from sunset Friday to sunset Saturday. Initially the Whales said it was impossible but, in true Japanese fashion, agreed to discuss the matter. After a few days, they revealed a plan that avoided loss of face by either party, which is paramount in resolving differences in Japanese culture. Millán’s name quietly disappeared from the Friday night and Saturday lineups, but he was expected to play every Saturday night and Sunday game. When the Whales released him after the 1980 season, Millán had made 1,139 plate appearances with only 52 strikeouts. He had also hit the second grand slam of his professional career. Even though he was approached informally by the club from Nagoya, Félix decided it was time to retire. That feeling lasted about as long as a trans-Pacific flight back to Puerto Rico, and he soon accepted an offer to play with the Red Devils of Mexico City. However, Mexico wasn’t Japan, nor was it the big leagues. After only one year Millán returned to Puerto Rico to retire.

Although officially retired, Millán did not fully leave the game. As of 2014 he continued making appearances for the Mets and Major League Baseball, including trips to Italy and Taiwan as an MLB instructor. In the 1980s he worked as an infield instructor18 for the Mets’ rookie league in Port St. Lucie, Florida, and for a time worked as Latin American coordinator for the Mets’ minor-league system. Millán played for the St. Lucie Legends of the Senior Professional Baseball Association in 1989, hitting .269 in 31 games. For a couple of years, he directed a baseball academy in Savannah, Georgia,19 and as of 2014 continued to be involved with the Félix Millán Little League, established in New York in 1977.20 He was named to the Braves 400 Club’s All-Time Atlanta Braves Team in 2001.21 As of 2014 he lived in Puerto Rico and Florida.

Last revised: June 17, 2015

This biography is included in “Puerto Rico and Baseball: 60 Biographies” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Edwin Fernández.

Sources

Millán, Félix, with Jane Allen Quevedo, Tough Guy Gentle Heart. (West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: Infinity Publishing, 2012).

Millán, Félix, with Jane Allen Quevedo, El Pelotero con un corazón noble (Ringgold, Georgia: Aspect Books, 2013).

Torre, Joe, with Tom Verducci, The Yankee Years (New York: Doubleday, 2009).

Fernandes, Victor, “Millan hoping to produce future major leaguers at academy,” Savannah (Georgia) Morning News, August 18, 1998.

Leggett, William, “Mutiny and a Bounty,” Sports Illustrated, October 29, 1973. sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1087941/index.html.

Baseball Digest

Sports Illustrated

The Sporting News

Baseball Almanac (baseballalmanac.com)

Baseball Reference (baseball-reference.com)

Bleacher Report (bleacherreport.com)

Braves 400 Club (braves400.org)

New York Press (nypress.com )

Retrosheet (retrosheet.org)

SABR Baseball Biography Project (sabr.org/bioproject )

The Baseball Index (baseballindex.org)

Graczyk, Wayne, “BayStars continue burgeoning baseball tradition in Yokohama,” The Japan Times Online, November 20, 2011. (japantimes.co.jp/text/sb20111120wg.html)

Hulka, James, “All-Time Braves Lineup,” Bleacher Report, August 5, 2008. (bleacherreport.com/articles/44585-all-time-braves-lineup).

Madio, Vinny, “New York Mets All-Time Lineup,” Bleacher Report, August 5, 2008. (bleacherreport.com/articles/44494-new-york-mets-all-time-lineup).

Ragus, Jonathan, “The Ultimate Mets Fantasy League,” Bleacher Report, May 28, 2009. (bleacherreport.com/articles/186891-the-ultimate-mets-fantasy-league.)

Stowe, Rich, “MLB Power Rankings: Every Team’s Greatest Second Baseman in History,” Bleacher Report, June 1, 2011. (bleacherreport.com/articles/713346-mlb-power-rankings-every-teams-greatest-second-baseman-in-history).

Notes

1 Sources for player transactions and statistics are Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

2 Shale Briskin, “New York Mets: Top 10 Second Basemen in Team History,” Bleacher Report, June 22, 2011 (bleacherreport.com/articles/736774-new-york-mets-top-10-second-basemen-in-team-history).

3 Felix Millán with Jane Allen Quevedo, Tough Guy Gentle Heart (West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: Infinity Publishing, 2012), 129; Millán with Quevedo, El Pelotero con un corazón noble (Ringgold, Georgia.: Aspect Books, 2013), 106.

4 In this case, “Double A” does not refer to the minor-league classification used in Organized Baseball; it was the name of that particular professional league in Puerto Rico.

5 Ken Ross, “Hub Kittle,” SABR BioProject, SABR.org/bioproj/person/4d152362 (Retrieved November 7, 2010).

6 Baseball-Almanac.com

7 Laurence Leonard, “Ambitious Millan-Cox Duo Braves’ Box-Office Beauts,” The Sporting News, August 26, 1967, 31.

8 Gary Ronberg, “Felix Is One Sweet Ballplayer,” Sports Illustrated, July 22, 1968. (sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1081411/index.htm).

9 Wayne Lockwood, “Felix Millan Close to Perfect Player,” Baseball Digest , October 1969, 56-58.

10 Ronberg.

11 Ronberg.

12 Lockwood.

13 Barry Duchan, “Trades From the Past – Millan and Stone for Gentry and Frisella,” Mikes Mets (mikesmets.com/2007/11/trades_from_the_past_millan_an.html).

14 Ron Fimrite, “Buffoonery Rampant,” Sports Illustrated, October 22, 1973 (sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1087919/index.html).

15 Joe Torre and Tom Verducci, The Yankee Years (New York: Doubleday. 2009), 516.

16 Jim Albright, “Japanese Best Nine Winners,” Baseball Guru (baseballguru.com/jalbright/best9.htm).

17 Robert Whiting, “You’ve Gotta Have ‘wa,’” Sports Illustrated, September 24, 1979 (sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1095410/).

18 Paul Gutierrez, “Links in the Chain,” Sports Illustrated, March 22, 1999 (sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1015386/index.html).

19 Victor Fernandes, “Millan hoping to produce future major leaguers at academy,” Savannah Morning News, August 18, 1998 (savannahnow.com/stories/081898/SPTmillanfeature.html )

20 “Loisaida Little League,” July 4, 2007 (nypress.com/loisaida-little-league/).

21 “Braves 400 Club’s All-Time Atlanta Braves Team” (braves400.org/event_gameboree2001_alltime.html).

Full Name

Felix Bernardo Millan Martinez

Born

August 21, 1943 at Yabucoa, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.