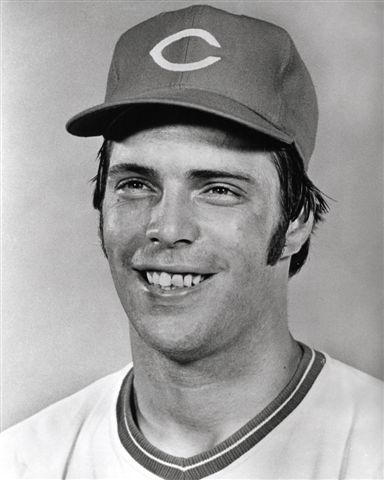

Will McEnaney

In his youth, Will McEnaney was a mischief-maker. In his adulthood, mischief became roistering, somewhat to the detriment of McEnaney’s career as a National League pitcher. Still, he posted a few achievements, including sterling performances as a reliever for the Reds in the 1975 and 1976 World Series.

In his youth, Will McEnaney was a mischief-maker. In his adulthood, mischief became roistering, somewhat to the detriment of McEnaney’s career as a National League pitcher. Still, he posted a few achievements, including sterling performances as a reliever for the Reds in the 1975 and 1976 World Series.

William Henry McEnaney was born, with twin brother Michael, on February 14, 1952, in Springfield, Ohio, one of five children (four boys and one girl) born to Bill and Eleanor McEnaney. Bill worked at International Harvester and Eleanor was a hospital nursing supervisor.

The mirror twins were constant companions. They were identical in every way except that Will was left-handed and Mike right-handed. Their Springfield North High baseball coach, Don Henderson said he could tell them apart by their mannerisms. Mike was more serious, Will was a little “loosey-goosey.” 1

Through youth leagues Will was usually on the mound and although Mike did pitch he was usually behind the plate. They played in the Babe Ruth League, were selected to its all-star teams, and won the 15-year-old state championship.

The mischievous twins often exchanged identities. In school they frequently attended each other’s classes. One time Mike had to answer questions in Spanish (Will didn’t take Spanish) to prove his identity. In a baseball game Will was scheduled to pitch four innings and Mike three, so they persuaded Coach Henderson to allow them swap jerseys. The opposition thought they were facing an ambidextrous pitcher. They were known to exchange identities with female companions, even changing clothes in a restroom during a double date.

Because of his behavior, Will’s high-school baseball career was limited to his sophomore season, when he finished 8-2 with a 0.91 ERA and 122 strikeouts in 69⅓ innings. Then as a junior, he was caught drinking at a drive-in movie and the next year was involved in an altercation at a school basketball game that led to the discovery that he had been drinking. He was suspended athletically both years. Henderson recalled, “Will was a joy to coach. He loved baseball, worked hard and played hard. But off the field he was as ornery as cat dirt.”2

During his high-school years McEnaney played for a summer traveling team. Scouts took notice of Will’s abilities. A call to Reds’ scout Cliff Alexander from umpire and scouting bird dog Warren Barnett brought Alexander to town for a closer look. That night McEnaney pitched five no-hit innings against an adult team, striking out 13. Suitably impressed, the Reds selected him in the eighth round of the June 1970 amateur draft, held the same day as his high-school graduation. “I was out all night with my buddies. The next morning I came home and the morning paper had already come and my mom is saying, ‘You got drafted.’ Hell, I thought she meant the Army.”3

Though his traveling-team coach tried to convince him that he might do better financially in the January Secondary Phase Draft, McEnaney signed with the Reds for a $3,500 bonus. “Growing up I would follow guys like Frank Robinson, Vada Pinson, Jim O’Toole, Jim Maloney,” McEnaney recalled. “I thought there would be nothing greater than to play for them one day.”4

Harvey Haddix, the Reds pitching coach in 1969, was a local resident. Bill McEnaney took his son to Haddix’s farm for some advice. Harvey’s advice: “Will, don’t get married until after you finish playing ball. It will distract you…”5 A week later McEnaney left for the Reds’ rookie camp.

“I almost quit in Florida. Ron Plaza, an instructor, drill-sergeant kind of guy, and Russ Nixon ran the camp. All we did was run. Florida in June. I wasn’t used to it, the discipline, constantly being schooled on baseball situations. We would drill, then practice, practice, practice. We didn’t play any games. Just practice and run. I had no idea that it would be like that. I was miserable and homesick, but my dad said, ‘Stick it out.’” Reds scout George Zuraw told him, “You’re just flakey enough to make it to the major leagues.”6 At the end of the camp, McEnaney was sent to the Sioux Falls Packers, with whom he was ineffective, leading the Northern League in losses, hits, and earned runs. His record was 3-10 with a 5.17 ERA in 87 innings.

That fall in the Instructional League, McEnaney began to flourish, posting a 1-0 record and 0.82 ERA in 22 innings. He followed with a breakthrough 1971 season with the Tampa Tarpons of the Florida State League, finishing 14-5 with a 2.44 ERA in 181 innings. “I’ve learned two things this year,” he told a sportswriter back home. “To have patience with my teammates and to throw a strike when I need it.”7 Another fine season followed with the Double-A Trois-Rivieres (Quebec) Aigles, recording an 11-6 record and 2.80 ERA in 138 innings and making the Eastern League All-Star team.

He was assigned to the Triple-A Indianapolis Indians in 1973. Manager Vern Rapp taught him to throw a slider. He also learned to control his temper. Once a poor performance meant a quick shower. In the locker room he destroyed benches and lockers. Rapp, also known for a temper, told McEnaney, “There are other pitchers who would like the opportunity to pitch in the American Association.” “I got the message,” McEnaney recalled. “I decided to curb my temper for fear of hurting my wallet and physical well-being.”

But he continued to frustrate Rapp with other clowning like walking an invisible dog around the stadium. After a tough loss, the manager yelled, “McEnaney, get that damn dog out of here.” He was the “life” of every party. Rapp caught him with a woman in the hotel past curfew and threatened to fine him. He also gave McEnaney some advice: “Get married. … Settle down,” contradicting Haddix’s advice.8

McEnaney’s 1973 statistics were disappointing (9-9 with a 3.92 ERA), though he earned a victory in the league All Star game. The following spring the Reds determined that he would be better suited as a reliever. His fastball and slider were ready, but his curveball was below average. Relieving suited him, as he collected two wins and five saves in 29 appearances for Indianapolis in 1974. McEnaney was called up by the Reds on July 2. “Vern Rapp had a bigger smile on his face when he told me than I did,” he said. 9

The rookie was nervous his first time in the Reds clubhouse, having heard stories about rookie hazing. But a teammate reassured him. Remembered McEnaney: “My shoes were really horrible, all scuffed up, and the cleats were all worn down.” Scolded Peter Rose, “Hey, you can’t wear those. Can you fit into a 9½?” Inside Rose’s locker were 30 pairs of shoes. “Pick out a couple of pair,” Rose said. “Good luck, have fun up here.”10

“A day after I got to Cincinnati they put me in against the Dodgers. I was never more nervous in my life. … I was scared to walk out on the field. The crowd noise was awesome and when I got on the mound and looked around, it was scary. It so happens the first batter I faced was the Dodger pitcher, Tommy John. My first pitch I threw between his legs.”11 McEnaney retired the first three hitters he faced on infield popups and held the Dodgers scoreless on one infield single in two innings pitched. His first save came on July 7 against the Cardinals and he got his first win ten days later in a 12-inning victory in St. Louis.

Although McEnaney was disappointed in the amount of work he received (27 innings), pitching coach Larry Shepard was encouraged. “He does a creditable job for us,” said Shepard. “But he is not comfortable on the mound yet. Will must learn to change speeds on all his pitches.”

McEnaney continued to live the night life to its fullest. Fellow Reds pitcher Pat Darcy remembered, “Sparky called Will McEnaney and me in his office at … spring training. We were roommates. He told us to behave … reminded us about curfew. Merv Rettenmund would call our room and imitate Sparky. … One night we went out, got some beer and some pizza and went back to the room and the phone rang and we thought it was Rettenmund. McEnaney picked it up but it was Sparky. McEnaney said some things. … All I could hear was Sparky yelling!”12

McEnaney got off to an excellent start in 1975. The other left-handed relief pitcher on the club, Tom Hall, was traded in April. By May 6 McEnaney was the only Reds’ reliever with a save.

“I can’t say enough about McEnaney,” said Sparky. He has really done a job for us … has tremendous courage. He is an unusual young man.”13 McEnaney ended the season with 91 innings of relief, five wins, 15 saves, and a 2.47 ERA.

On October 9, two days before the World Series, he and his wife, Lynne, became parents for the first time with the birth of their daughter Faith. He pitched in five World Series games against the Boston Red Sox. The most memorable moments were in the final two games. In the ninth inning of Game Six, with the game tied, runners on second and third and none out, McEnaney came in and intentionally walked Carlton Fisk to load the bases, then got Fred Lynn to fly out into a double play and retired Rico Petrocelli on a groundball. The next evening he was called upon to pitch the final inning of the Reds’ 4-3 victory in Game Seven, retiring the Red Sox one-two-three. McEnaney jumped into catcher Johnny Bench’s arms, creating a memorable photo that appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated.

That winter McEnaney was in demand on the banquet circuit, and he made so many speeches that his teammates nicknamed him Face. He had another contract dispute before the 1976 season. “Had I not been so selfish, I would still be in the majors today,” McEnaney said in 1985. “I wanted a $6,000 raise, and they wanted to give me $1,000.”14

The Reds had another great year but the same couldn’t be said for their erstwhile ace reliever. As he struggled, his role diminished. “Last year I had to learn to adjust to success. This year I have had to learn to handle defeat,” McEnaney said.15 His 4.85 ERA was the worst on the staff, but he turned it around against the Yankees in the World Series with saves in Games Three and Four of the Reds’ sweep, allowing no runs in 4⅔ innings. With the Game Four save, he became the first National League pitcher to finish consecutive World Series on the mound.

In December the Reds traded McEnaney and first baseman Tony Perez to the Montreal Expos for pitchers Woodie Fryman and Dale Murray. Devastated by the deal, the death of his mother, and a painful divorce, McEnaney was soon drinking frequently and experimenting with drugs. “I chose to do it,” he said. “I was not a heavy user, but every time you do drugs you abuse yourself.”16

McEnaney’s pitching improved a bit in 1977, as he posted a 3.95 ERA in 69 games, but not enough to impress Expos manager Dick Williams, who commented, “We did not get anything from our bullpen, especially the left side.” Near the end of spring training of 1978, Montreal sent him to the Pittsburgh Pirates for pitcher Timothy Jones. In June he had pitched just 8⅔ innings and had a 10.38 ERA, prompting his demotion to Triple-A Columbus. Legend has it that brother Mike even dressed for a game and sat in the Clippers bullpen, not endearing him to the Pirates further. At the end of the season, after putting up a 6.24 ERA, he was released.

In December 1978, while driving drunk, McEnaney crashed his car into a house and almost died. Realizing that his life was spinning out of control, he moved to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, to be with his sister, Kathy. There he met the woman who was to become his second wife, Cindy, who introduced him to a psychologist. With Cindy’s support, he said, he became clean and sober. “She constantly told me, ‘You’re better than this. You’re smarter than this,’ ” he said.17 The therapist helped him regain the aggressiveness he needed to be a successful athlete. He signed with the St. Louis Cardinals, and after spring training in 1979 he was sent to their Triple-A team in Springfield, Illinois. He was recalled by the Cardinals a month into the season and pitched in 45 games out of the bullpen with a 2.95 ERA. But he was released at the end of spring training in 1980, ending his big-league career. He hooked on with Nashville of the Southern League and posted a 1.44 ERA in 22 games. McEnaney went to spring training in 1981 with the Detroit Tigers but did not make the club. That season he pitched with Tabasco of the Mexican League, then spent 1982 with Tulsa and Denver in the Texas Rangers’ system.

“Finally Cindy and I decided to chuck it all and get on with our lives,” McEnaney recalled. “I didn’t want to hang on and become an embarrassment to myself or my family. … It was time to look at the facts. I chased dreams that no longer brought in money to support them. I sold cars for a while but that wasn’t me. Then I got into broadcasting”18

McEnaney attended broadcasting school and got a job covering covered the University of Miami Hurricanes for WGBS, a Miami radio station, in 1984. He also became a successful painting contractor.

The allure of playing baseball hit McEnaney twice more. When the Miami Marlins of the Florida State League began playing without a major-league affiliation in 1985, he and 13 other former big leaguers gave baseball another try. He pitched in 39 games. Four years later, in 1989 he signed to pitch for his old Montreal manager Dick Williams, with the West Palm Beach Tropics in the Senior Professional Baseball Association, but spent the entire season on the disabled list.

Later McEnaney owned a bathtub refurbishing business until the economy caused the building industry to decline. Still living in the Palm Beach area with Cindy as of 2012, he worked for Dick’s Sporting Goods and signed on as the scoreboard operator for the Jupiter Hammerheads of the Florida State League. He has three children, Faith, Weston, and Alex.

Last revised: May 1, 2014

This biography is included in the book “The Great Eight: The 1975 Cincinnati Reds” (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Mark Armour. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Notes

1 Don Henderson, interview with author, January 26, 2011.

2 Ibid.

3 Greg Rhodes and John Eraldi, Big Red Dynasty: How Bob Howsam and Sparky Anderson Built the Big Red Machine. (Cincinnati: Road West Publishing, 1997), 173.

4 Tim Archdeacon, “Inside Moves, A New Coat of Paint for Opening Day,” Miami News. 2.palmbeachpost.com/archives, April 7, 1986.

5 Joe Posnanski. Joe’s Blog. joeposnanski.blogspot.com. August 2009.

6 Rhodes and Eraldi, Big Red Dynasty, 176.

7 Springfield Sun, August 13, 1971.

8 Joe Posnanski, Joe’s Blog.

9 Springfield Daily News, July 2, 1974.

10 Rhodes and Eraldi, Big Red Dynasty , 201.

11 Archdeacon, “Inside Moves.”

12 John Ring, “Pat Darcy on Sparky, the Big Red Machine and the ball,” theredsreport.com, January 15, 2011.

13 Springfield Sun, May 6, 1975.

14 Dean Chang, “When Will McEnaney Left Baseball, He Left the Only Life He Knew. Now He`s Back for One Last Shot. Reincarnation of a Reliever,” Sun-Sentinel, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, July 1, 1985.

15 Ibid.

16 Rhodes and Eraldi, Big Red Dynasty, 266.

17 Camille Bersamin, “Will McEnaney, Sports Illustrated, July 17, 2000.

18 Archdeacon, “Inside Moves.”

Full Name

William Henry McEnaney

Born

February 14, 1952 at Springfield, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.