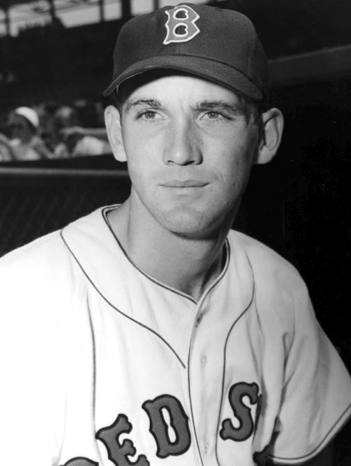

Frank Sullivan

Former Red Sox pitcher Frank Sullivan wore uniform number 18 with distinction before later Sox pitchers Jason Johnson, Tomo Ohka, and Daisuke Matsuzaka were born. During his eight seasons with the team, Sullivan won 90 games and was named to two American League All-Star teams. As of the end of the 2009 season, his career win total with the Red Sox ranked 15th in club history.

Former Red Sox pitcher Frank Sullivan wore uniform number 18 with distinction before later Sox pitchers Jason Johnson, Tomo Ohka, and Daisuke Matsuzaka were born. During his eight seasons with the team, Sullivan won 90 games and was named to two American League All-Star teams. As of the end of the 2009 season, his career win total with the Red Sox ranked 15th in club history.

To say Frank Sullivan has led an interesting life would be an understatement. He has traveled the world, practiced with the Boston Celtics, graced the cover of The Saturday Evening Post, and played the Old Course at St. Andrews. After his baseball career was over, he moved to Kauai in the Hawaiian Islands with his great pal, former Red Sox catcher Sammy White. Sullivan had never set foot on Kauai before.

Frank had a very adventuresome career in the major leagues as well. His first full year in the majors was with the 1954 Boston Red Sox, a team that won only 69 games. Sullivan achieved a very respectable 15-12 record for a Red Sox team that had a winning percentage of .448.

Sullivan had another excellent adventure with the 1961 Philadelphia Phillies. “I shudder whenever I think of that team,” he offered from his home in Lihue, Kauai. “We had lost five straight games and then we went out and won one. Right after that we lost 23 games in a row. That one win broke up an amazing losing streak.”

Franklin Leal Sullivan was born in Hollywood, California, on January 23, 1930, and grew up in nearby Burbank. “I grew up during the Depression, but my father always had a good job and he was always encouraging me to play sports. He had been a pretty good athlete and he wanted me to compete. Leal Earl Sullivan was a machine operator, an independent contractor who worked for a cannery in Glendale, California. He was a native Californian. Frank’s mother was Olive L. Franklin, born in Albuquerque in the New Mexico Territory (before statehood). Frank had an older sister, Carol. As a teenager he played some baseball, shot some hoops, and chased pretty girls. His father pushed him toward sports,

“I remember one time I got a job at a service station and he showed up there and said, ‘Go play ball.’ He didn’t want me working. I was a big kid, but I was coordinated, so I did well. Actually basketball was my first love then, and baseball was kind of filler.

“I had an offer of a basketball scholarship to Stanford, and I was leaning in that direction, but Red Sox scout Jack Corbett saw me pitch and he wanted to sign me. Jack saw me pitching American Legion ball, but there was another left-handed pitcher named Frank Sullivan, and I think he showed up thinking he would see him. I went to Boston with Jack to talk about signing a contract.”

This was in 1948. “We flew to Boston for a tryout at Fenway Park. We were staying at the Somerset Hotel in Kenmore Square, and we ran into Red Sox pitchers Mickey McDermott and Chuck Stobbs. They invited me to join them. I took my first cab ride ever, to downtown Boston, and I followed Mickey into the Arrow shirt store. Mickey bought a dozen new shirts, put one of them on, and left the one he was wearing in the store. That’s when I made the decision to sign a pro baseball contract if it was offered.”

Sullivan’s early days in the minor leagues were painful. “I didn’t have a lot of success, and to tell you the truth, I was homesick. I had to do some growing up fast.” He appeared in eight games that year, four each with the Oroville Red Sox, a Class D club in the Far West League, and the San Jose Red Sox, Class C in the California League. His combined record was 1-4 with a 7.67 earned run average. He was just getting his feet wet.

In 1949, Frank got in a full year with San Jose, 172 innings of pitching, and posted a 12-10 record with a strong 2.83 ERA. In 1950, with the exception of five innings thrown for the Double-A Birmingham Barons, Sullivan pitched for Scranton Red Sox (Single A) with a 3-6 record (6.29 ERA). A bad arm kept him from pitching more than 83 innings for Scranton.

Sullivan’s nascent professional baseball career was interrupted after the 1950 season by two years of service with the Army in the Korean War. He spent 4½ months on the front line in combat. It was an experience that made a lasting impression on him. He was awarded the Combat Infantryman Badge and was honorably discharged as a staff sergeant in 1952.

“I didn’t really become a pitcher until 1953, when I was with the Red Sox farm club in Albany, New York, in Class A ball. That was also the year I discovered I wasn’t considered a prospect. I had experienced a little arm trouble and I went to our manager, Jack Burns, to tell him I was fine and that I wanted to pitch. He said, ‘I know you’re fine, and I want to get you in there, but the Red Sox told me I have to pitch the prospects.’ But he did work me in and I pitched pretty well.

“It was around that time that my catcher, Len Okrie, came out to the mound and said, ‘Stop worrying about what you are doing out here, and start worrying about what is happening at home plate.’ It was as if a light went on for me. From that point on I was a different pitcher.”

Sullivan performed well for Albany, 9-6 with a 1.73 ERA. “Later that season Jack Burns was in Boston attending a meeting at Fenway Park. Red Sox manager Lou Boudreau said, ‘Don’t we have anyone in our organization who can throw strikes?’ And Jack said, ‘I’ve got a guy who can throw strikes.’ That’s when I was on my way to Boston.”

Baseball writers often referred to Frank Sullivan as the Boston Skyscraper, because at 6-feet-7 he was one of the tallest pitchers in major-league history. “My father was 6 feet and my mother was 5-5, but I was always tall. I found it to be a big advantage as a pitcher, especially coming in sidearm the way I usually did.”

Sullivan made his major-league debut on July 31, 1953, against the Tigers in Fenway Park. He entered the game in the fifth inning. He pitched two innings, giving up no hits and no runs, while walking one and striking out one. He was not involved in the decision. He appeared in relief 14 times that year. “The best thing for a pitcher is to come up as an unknown,” he said. “I had made the jump all the way from A ball so the hitters didn’t know anything about me. And I could throw my slider for strikes. They would be looking for a fastball and I would come in with a slider for my out pitch.” Sullivan’s first major-league win came on September 13, 1953, in relief of Mel Parnell against the White Sox in Boston. He gave up the lead in the top of the eighth, but the Red Sox rallied for two runs in the bottom of the frame, to make a winner of the rookie pitcher.

Frank started the 1954 season in the bullpen for the Red Sox, but a teammate’s misfortune created a spot for him in the starting rotation. On April 24, Senators pitcher Mickey McDermott, whom the Red Sox had dealt to Washington the previous December, broke southpaw Parnell’s left wrist with an errant pitch. The 24-year-old Sullivan took advantage of this opportunity, putting together 15 wins, tops among Red Sox pitchers. He led the staff in ERA, innings pitched, complete games, and strikeouts.

Sullivan pitched well at the beginning of the following season, and his strong start earned him a spot on the 1955 American League All-Star team. The American League jumped out to an early lead in the first All-Star Game played in Milwaukee, but Sullivan was called in to squelch a National League rally in the eighth inning. “When I was walking in from the bullpen in center field, Mickey Mantle said, ‘Sully, you better shut them down or we’re going to miss the cocktail hour.’ I was too nervous to reply.” He might have shut down the NL, but an error allowed an inherited runner to score and the game went into extra innings.

“I got out of the inning and then I shut them down in the ninth, tenth, and eleventh. I was pitching to guys like Musial, Mays, and Aaron, but I managed to hold them. Then Musial came up for the second time and hit a ball into the right-field stands. My catcher, Yogi Berra, came up to me later in the locker room and said, ‘I should have told you he was a high fastball hitter.’”

Frank continued his winning ways in the second half of the season, and the Red Sox nipped at the Yankees’ heels in the American League pennant race before running out of gas in mid-September. Sullivan led the American League in games started and innings pitched, and his earned run average of 2.91 was fifth best in the league. His 18 wins tied for the American League lead and led the Red Sox staff for the second year in a row.

Like most pitchers before the era of the designated hitter, Sullivan enjoys talking about his hitting prowess. His favorite hitting memory is his only triple, hit in the bottom of the second inning on April 17, 1955, off Orioles starter Saul Rogovin. “The ball hit the top of the left-field wall and bounced away. And I think the left fielder fell down. I went sliding into third base and they almost threw me out. After I dusted myself off, our third base coach, Jack Burns, shook my hand and said, ‘I want to introduce myself. I’m the third base coach. You haven’t spent a lot of time here.’” Sullivan drove in two runs with the three-bagger as the Sox trounced Baltimore, 14-5.

Sullivan was quick to share credit for his pitching success with his batterymate and longtime friend, Sammy White. “Sam was my first roommate with the Red Sox and we hit it off right away. We were so attuned that Sam would only give me signs for the first three innings of a game. By then we would have established our pattern and he didn’t have to give me a sign. He knew what was coming and I knew he would be ready for the pitch I would throw. It was almost uncanny.”

In 1956, Sullivan compiled a career-best winning percentage of .667, which ranked seventh in the American League and second (Tom Brewer was 19-9) for the Red Sox. He was named to the American League All-Star team for the second successive year, though this time he did not pitch.

In the mid-’50s if the front office told you to drive to Stockbridge, and bring your uniform, that’s exactly what you did. On an off day in 1956, Sullivan, Sam White, and Jackie Jensen were told to motor west to the western Massachusetts town. “When we got there we were greeted warmly by a small, slim man, whose name meant nothing to me. He posed us and took a number of pictures, explaining that the background would be the locker room we used in Sarasota, Florida, for spring training. I remember ragging on Jackie Jensen on the way back, saying the trip was all his idea, and the photographer didn’t seem to know what he was doing.

“The following March, I pick up The Saturday Evening Post, and there we were on the cover. The man was an illustrator, not a photographer, and if you look closely, you’ll see we are wearing street shoes, not spikes. The cover was titled ‘The Rookie’ and the man’s name turned out to be Norman Rockwell.”

The 1956 Red Sox finished fourth in the American League for the fourth straight year. Sullivan’s earned run average of 3.42 and his 33 pitching starts led the Red Sox pitching staff. His 14 victories were second to teammate Tommy Brewer’s 19.

The break after the 1956 season is one of Sullivan’s favorite memories. “In the past, I had always gone home to California to work or gone to Mexico to pitch winter ball. Sam [White] convinced me to stick around and make personal appearances around New England. We were so in sync that we developed a pretty good presentation and I think we were making more than we did playing ball.

“This one time we were booked to speak way up in Presque Isle, Maine. We get there and they have us scheduled in a very large auditorium, before a huge audience. We were on between a tap dancer and a banjo player. I was a little overwhelmed since we usually appeared in a more intimate setting, but Sam assured me he would take care of everything.

“He stood before the microphone and announced, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, my name is Sam White and I am a catcher for the Boston Red Sox. Normally I would be here to talk to you about baseball, but not tonight. Tonight I am here to introduce the funniest man I know. In fact, he is so entertaining that I am coming down to sit with you.’ And with that, he left the stage. Fortunately winter in Presque Isle is pretty boring. Nobody threw anything.”

Frank also made a significant contribution to a Boston sports team during this eventful offseason. “It was the season that Bill Russell joined the Celtics, and Jack Nichols was the other center. (Nichols) was finishing up dental school and he told Red Auerbach that he could play in the games but he didn’t have time to practice. Nichols had played college basketball with Sam White, and Jack asked me if I would replace him in practice.

“I said I would, and two things happened every practice. Every time I was chosen to be on one team for a scrimmage, the other team clapped, and I would end up trying to guard Tom Heinsohn, who was the NBA’s Rookie of the Year that season. Auerbach used me all pre-season and asked me to think about playing two sports, but I told him I was already maxed.”

The 1957 Red Sox improved to third place in the American League, trailing the pennant-winning Yankees and the second-place Chicago White Sox. Apparently Sullivan’s winter training with the Celtics was offset by his time on the banquet circuit, as his personal win total held at 14. That win total ranked seventh in the American League, and his complete-game total of 14 ranked fourth. His ERA of 2.73, fifth in the league, topped the Red Sox staff that year, and his 240? innings pitched led the team as well. The ERA figure was helped by the three shutouts he recorded in 1957, matching the mark he’d posted in both ’54 and ’55.

It was in this time period that Sullivan became a sailor. “I bought a 38-foot ketch-rigged sailboat in Westerly, Rhode Island. Somehow I managed to sail it back to Winthrop (near Boston). Looking back on it, it probably would have been good to take a lesson or read a book. I decided to sail down to spring training before the next season. I wish I could say I sailed down, but the truth is, we kind of bumped our way south.

“I finally made it to the Florida Keys, not without incident, and I docked at the marina in Islamorada. I called my teammate, Ted Williams, who came down to pick me up. We had a lot of laughs as I related my trip down. He had predicted that I would never make it.

“I spent one day helping Ted with a carpentry project and learned that the greatest hitter in baseball history didn’t own a tape measure. He picked me up the next morning with a boat in tow when it was still pitch-black. The sun was just rising as we reached the launch ramp, and I jumped out of the car looking to buy a case of beer. The next thing I knew he had the boat in the water and he was hollering, ‘Get over here, Bush, or I’m fishing alone.’

“We fished all day and his concentration was unreal. All we had with us was an apple apiece and some water. Ted worked every minute we were out there and I have never been more exhausted after a day of fishing. But just think, I spent eight years watching the best hitter and I even got to fish with the best fisherman.”

In 1958, the Red Sox finished third again. Sullivan continued his consistent pitching ways with 13 wins. It was his fifth straight season of double-digit win totals for the Red Sox. His 10 complete games tied Tommy Brewer for the team lead in that category.

After the 1958 season, Sullivan agreed to deliver a 42-foot Chris-Craft powerboat to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, for George Page, who owned the Colonial Country Club in Lynnfield, Massachusetts. He selected Sam White as his crew. White was selected more for his pleasant company than for his seamanship.

“I was told that Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey owned an island off the South Carolina coast. The closer we got to South Carolina, the better the idea of stopping by to say hello to Mr. Yawkey sounded. I located Cat Island, and after a quick stop we called and we were graciously invited for a visit. Two World War II Jeeps met us at a long pier and we were driven to the main complex. Mr. Yawkey personally showed us his private game preserve. They treated us to a great dinner and we all had many laughs. The evening came to an end shortly after Mr. Yawkey gave Sam some hitting advice, using a broom as a bat.”

The big change for the Red Sox in 1959 was a shift in their spring training headquarters. The team had trained in Sarasota, Florida, since 1933, but in 1959, spring training was shifted to Scottsdale, Arizona. “I hated training in Arizona,” Sullivan recalled. “You couldn’t raise a sweat, you couldn’t get loose. And there was nothing to do in Scottsdale.

“I was pitching against the Cubs in Mesa, Arizona, and the mound was terrible. I just couldn’t get comfortable. I felt a tweak in my back and I knew I was in trouble. I felt back spasms all the way back to Scottsdale. Then we broke camp, and flew to New York to open the season. It was raining there, but I wanted to get my running in. The next thing I knew I was very sick and I was diagnosed with pneumonia. They sent me back to Boston by train, and I stayed in Sancta Maria Hospital in Cambridge until I recovered.”

Frank Sullivan never did get on track during the 1959 season. He ended with a record of 9-11, his first losing season in seven years in the major leagues. The following season was worse, as his record fell to 6-16. On December 15, 1960, he was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies for 6-foot-9 pitcher Gene Conley. Some have dubbed it the tallest trade in major-league history. Conley stood out among baseball players because of his parallel career as an NBA player for the champion Boston Celtics.

“The Red Sox sent me a telegram, ‘You have been traded to the Phillies, good luck.’ I remember saying to the telephone operator who read it to me, ‘Honest?’ I was destroyed. I talked to George Page, whom I considered my second father, and he advised me to tell the Phillies that I wasn’t sure I wanted to play any more because I could make more money working for George.

“When Gene Mauch, who managed the Phillies called that evening, I told him I was going to call it quits and stick with my offseason job. He said, ‘How much do you need, Sully?’ That’s when I realized I wasn’t prepared with an answer, and I told him $25,000. He replied, ‘That’s easy, Sully. You got it.’ Now you know why most players have agents.”

The 1961 season was Frank Sullivan’s worst in the major leagues. He won three games and lost 16, playing for a Phillies team that lost 107 games in a 154-game season. “We were terrible,” Sullivan recalled. “Our best hitter batted .277. I was awful, but Robin Roberts was 1-10, and he’s in the Hall of Fame.” Sullivan also had six saves to lead the Phillies.

After starting the 1962 season with a 0-2 record, he was released by the Phillies and signed immediately by the Minnesota Twins. “I got to play for my great friend Sam Mele, who had been a teammate on the Red Sox. He was one of the best managers I ever had.”

Sullivan rebounded nicely for the Twins, going 4-1 in 21 relief appearances during the balance of the 1962 season. His tenure with the Twins started magnificently. He did not allow an earned run until his sixth appearance, a streak of 12? innings. His ERA remained below 1.00 until he gave up five earned runs in an inning of work against his old mates, the Red Sox.

Sullivan was used exclusively in relief again to start the 1963 season. However, after just 10 appearances and 11 innings, the Twins released him. After 11 seasons in the major leagues, his professional baseball career was over.

“It’s a big adjustment for a player when his career ends. All those years, for seven months each season, you walk into the clubhouse and there’s a fresh uniform waiting for you. And then, just like that, it’s over.” After his release, Sullivan went to work for Henry Hinckley, a noted sailboat builder, for the rest of that summer and fall in Southwest Harbor, Maine.

“I did a number of different things over the next year or so. Then one day Sam White said, ‘We ought to go someplace totally different and start over.’ That appealed to me, and an island seemed to make sense to both of us. We thought a little bit about the Caribbean, but that didn’t feel right. Finally, we settled on Kauai in the Hawaiian Islands.”

Kauai is the oldest and northernmost of the main Hawaiian Islands. It is about a 20-minute flight from Honolulu. It is 550 square miles with a permanent population of a little over 50,000. It is also Frank Sullivan’s vision of paradise.

“Sam had been to Kauai for one day on his way to Japan with a barnstorming team. They played a game in Hanapepe, but didn’t stay overnight. I had never been there. From Maine, I wound my way to Kauai in February of 1964. We got a job with a helicopter company working construction. We built landing pads at different locations throughout the island. I had no idea what a hard worker Sam was. He would stick a cigar in his mouth and work all day.”

Asked if there were many Red Sox fans on Kauai, Frank laughed heartily. “Shortly after we got here, Sam and I put on a clinic for a bunch of little leaguers. I was throwing to Sam behind the plate, and we were really humming. When I walked off the field, this little kid said, ‘Who do you play for?’ I said proudly, ‘I played for the Red Sox.’ He looked me over and replied, ‘So do I.’ I knew at that moment that I was a long way from Boston. It was very humbling.

“My wife-to-be, Marilyn, joined us after about three months and she got a job as an executive secretary at the Kauai Surf Hotel. After a year of working construction, I took over the beach concession for the Kauai Surf. A couple of years later, I became the assistant golf pro there, and eventually I became the head pro.

“In 1978, Sam and I got certified by the PGA, and I’ve been the director of golf for a number of courses here over the years. I’ve been a golf consultant to the Grove Farm Company for almost 10 years now.”

Sam White died on Kauai in 1991. “Sam was my close friend for almost 40 years. I enjoyed every minute I spent with him,” Sullivan said. “He was like a brother to me.”

Frank looks back fondly on his years in Boston. “Those were wonderful years. I loved that city and the fans were great. I got to play for eight years with Ted Williams, and watch the greatest hitter ply his craft. He could tell you if he hit one seam, or two seams, of a ball that was coming at him at 100 miles per hour.”

He enjoys watching the games that are televised in Kauai, but gets mildly annoyed with the color commentators. “I’m amazed when I hear commentators like Tim McCarver and Joe Morgan telling the viewers exactly what is going through the minds of the players. I can remember standing on the mound at Fenway and thinking, ‘Damn, this is a nice day! What could be better? Here I am facing Mickey Mantle and he’s smiling at me.’ Of course I found out later that Mickey, and a bunch of his teammates, had spotted my VW Beetle behind the Kenmore Hotel, lifted it up on the sidewalk, and deposited it behind a telephone pole next to a brick wall. But there was no way that any announcer could have guessed what I was thinking.”

Frank and his wife, Marilyn, celebrated their 41st wedding anniversary in March 2007. They have a son, Mike, and a granddaughter, Kea, who beats Frank regularly at cards, and a grandson, Pono. Frank’s son Mark, from his first marriage, lives in Maggie Valley, North Carolina, and he has three children, Summer, Lauren, and Kevin.

In May 2005, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston exhibited the original painting of Norman Rockwell’s “The Rookie.” Frank and Marilyn traveled from their home on Kauai to take part in the museum”s public celebration of the well-known Saturday Evening Post cover. During that visit, this author had the pleasure of hosting Sullivan at his first major-league baseball game in more than 40 years. Frank was impressed by the extensive renovations to Fenway Park and the enthusiasm of the sold-out crowd.

During the five-year period 1954-1958, Sullivan was among the elite pitchers in major-league baseball. He averaged 15 wins per season, and was named to two American League All-Star teams. In 1957, his WHIP (walks and hits per nine innings) of 1.055 was a major-league best. Sullivan ranks in the top 20 among all Red Sox pitchers in eight important career categories.

In November 2008, Frank Sullivan was inducted into the Red Sox Hall of Fame at a ceremony in Boston. In 2009, his book Life Is More than Nine Innings was published by Editions Limited of Honolulu. Unlike many former ballplayers who can be hard to reach, Sullivan enjoys corresponding with people about baseball and would be pleased to receive e-mail at watash@hawaiiantel.net.

Sources

This biography is an adaptation of an article that originally appeared in Red Sox Magazine (2004:2). It is also based on innumerable conservations and e-mails with Frank Sullivan since 2004, including May 9, 2005 at Fenway Park, which was the first major-league game Frank had attended since 1963, and a visit at his home in Lihue, Hawaii, from January 31 to February 7, 2007.

Boston Red Sox Media Guide, 2009.

Frank Sullivan, Life Is More Than 9 Innings (Hawaii: Editions Limited, 2008).

Full Name

Franklin Leal Sullivan

Born

January 23, 1930 at Hollywood, CA (USA)

Died

January 19, 2016 at Lihue, HI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.