Harry Brecheen

Harry David Brecheen (pronounced Bruh-KEEN) was born on October 14, 1914, in Broken Bow, Oklahoma. He was the first of three children born to Texans Tom and Lucy (Tyree) Brecheen, who had settled in the small town near the Texas border when Oklahoma was still a territory. By the time Harry was 10, his family had relocated to Ada, then a city of fewer than 8,000 residents in the south-central part of the state. Harry was a scrawny kid and a natural left-hander who fought his teachers’ attempts to make him write with his right hand. More interested in sports than school, little Harry seemingly always had a bat, glove, fishing rod, or gun in his hand while growing up on the family farm on the outskirts of the city.

Harry David Brecheen (pronounced Bruh-KEEN) was born on October 14, 1914, in Broken Bow, Oklahoma. He was the first of three children born to Texans Tom and Lucy (Tyree) Brecheen, who had settled in the small town near the Texas border when Oklahoma was still a territory. By the time Harry was 10, his family had relocated to Ada, then a city of fewer than 8,000 residents in the south-central part of the state. Harry was a scrawny kid and a natural left-hander who fought his teachers’ attempts to make him write with his right hand. More interested in sports than school, little Harry seemingly always had a bat, glove, fishing rod, or gun in his hand while growing up on the family farm on the outskirts of the city.

Brecheen gathered most of his pitching experience in the local junior American Legion league where he supposedly won 65 games and lost just three times. Brecheen idolized Oklahoma native Carl Hubbell and hometown big leaguers Lloyd and Paul Waner, who generously supported baseball in Ada. The Tulsa Oilers of Class A Texas League invited 18-year-old Brecheen to try out with the club during spring training in 1933, but he was no match for seasoned players, many of whom had big-league experience.1 He returned to Ada, married his high-school sweetheart, Vera Caperton, in the fall, and was lucky to find a job in construction during the harsh times of the Depression. Brecheen also pitched in local semipro leagues and soon earned the attention of scouts despite his small 5-foot-10, 160-pound stature. According to St. Louis sportswriter Bob Broeg, Brecheen turned down a $175-a-month contract from the St. Louis Cardinals and a similar offer from the New York Yankees, claiming he could earn money as a semipro.2

Brecheen commenced his grueling eight-year odyssey in the minor leagues in 1935 as a fastball-curveball artist with poor control. With the help of former big-league pitcher and Ada businessman Homer Blankenship, he signed with the Galveston (Texas) Buccaneers of the Class A Texas League but was soon transferred to the Greenville (Mississippi) Buckshots of the Class C East Dixie League. After another shot with the Buccaneers in 1936, Brecheen was sent to the Bartelsville (Oklahoma) Bucs in the Class C Western Association and finished the season with a combined 6-22 record and 132 walks in 266 innings.

No one could have predicted Brecheen’s stunning success in 1937 with the Portsmouth (Virginia) Cubs (Class B Piedmont League). He had learned to throw a screwball a few years earlier from big leaguer and fellow Oklahoman Cy Blanton of the Pittsburgh Pirates, but had been unable to get it over the plate. “I owe an awful lot to (Portsmouth catcher) Dick Luckey,” Brecheen said. “Until I met him, I was just trying to throw the ball past hitters, always trying for strikeouts. But he worked on my control and showed me what it mean to think a game.”3 With his catcher’s patience, Brecheen perfected his screwball so that it broke down and away from right-handed hitters and into left-handers (the opposite break of his curveball). He went 21-6 and walked only 69 in 249 innings. The St. Louis Cardinals, acting on the advice of Eddie Dyer, then the president of the Cardinals affiliate in the Piedmont League, drafted the wiry southpaw.

Brecheen joined an organization that he had once derided as a “chain gang” for its poor salaries and vast farm system.4 He spent two years with the Houston Buffaloes of the Class A Texas League, going 13-10 in 1935 and improving to 18-7 in 1936, including a stretch of four consecutive shutouts and 38 consecutive scoreless innings.5

No team in the big leagues had a farm system as stacked with pitchers as the Cardinals in the late 1930s and early 1940s. Brecheen was also aware that Cardinals boss Branch Rickey preferred big, hard-throwing pitchers, like Mort Cooper and Max Lanier. After a productive spring, Brecheen made the Cardinals’ Opening Day roster in 1940, but the southpaw’s euphoria did not last long. After tossing 3⅓ innings (surrendering one unearned run) in three brief relief appearances, he was optioned to the Columbus Red Birds of the American Association, and didn’t make it back to big leagues until 1943 — the year after Rickey left the club. The years 1940-1942 played like a broken record for Brecheen. “Stymied” (according to The Sporting News) by the surfeit of Cardinals pitchers, Brecheen annually participated in spring training, then was optioned to Columbus, where he posted successive records of 16-9, 16-6, and 19-10.6

Brecheen was back in spring training with the reigning champion Cardinals in 1943 under vastly different circumstances. St. Louis had used its three options on Brecheen, and thus was forced to keep him on the big-league club or sell him. The club’s decision was made easier by World War II, which had already begun playing havoc with the Cardinals’ roster; among other things, the team lost 21-game-winner Johnny Beazley to the military.

Manager Billy Southworth saw the 28-year-old Brecheen as an ideal swingman. In his season debut, Brecheen tossed three innings of scoreless relief against the Chicago Cubs to notch his first big-league win. He extended his string of innings without allowing an earned run to 20⅔ (dating back to 1940) before yielding a run in a tough 1-0 loss on May 31 to the Brooklyn Dodgers in his first start and complete game. Pushed into the starting rotation with the loss of Howie Pollet to the war and Ernie White to injury, Brecheen won four of seven starts in August and limited opponents to a sparkling 1.89 ERA over 57 innings. While the Cardinals cruised to their second consecutive pennant, Brecheen posted a 9-6 record and a career-low 2.26 ERA in 135⅓ innings for the NL’s best staff.

In the Cardinals’ World Series rematch with the New York Yankees, Brecheen pitched three times, all in relief. After scoreless stints of one inning and two-thirds of an inning in losses in Games One and Three, he relieved Lanier to start the eighth inning in Game Four, with the score tied, 1-1. He surrendered a double to the first batter he faced, pitcher Marius Russo, who later scored the deciding run on Frank Crosetti’s fly ball. The Yankees closed out the Series the next game.

Cardinals beat writer Roy Stockton began referring to rookie Brecheen as “The Cat” because of his quick, feline-like reflexes on the mound and excellent fielding.7 “Harry the Cat” became such a recognizable nickname that papers did not need to mention Brecheen’s surname. Brecheen led or co-led the NL with a 1.000 fielding percentage three times (1944, 1948, and 1950), and had four additional errorless seasons (1940, 1943, 1952, and 1953) in which he did not log enough innings to qualify for the crown. He committed only eight errors in more than 1,900 major-league innings.

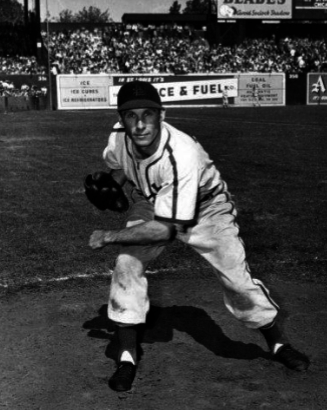

Throughout Brecheen’s career, sportswriters had a field day describing his appearance and small size. With blue eyes, dark blond hair and a weatherbeaten face, Brecheen was a “wiry [and] slender” country boy who felt at home in a Cardinals dugout filled with country boys like Lanier, Al Brazle, and Marty Marion.8 Bob Broeg described Brecheen as a “hollow-cheeked, bandy-legged son of Oklahoma’s red-clay country.”9 One of the most poetic characterizations came from syndicated columnist Red Smith, who saw Brecheen as “a scrawny little scrap of meat, just a fragment of whale bone and rawhide.”10 But Brecheen would not shy away from hitters. “[He] would buzz anybody,” said teammate Chuck Diering. “He was a mean pitcher; a tough competitor.”11

Brecheen got off to a hot start in 1944, shutting out the Chicago Cubs in his season debut and winning 13 of his first 15 decisions through August. He had an unflappable presence on the mound and rarely showed any emotion. “Deadpanned and apparently nerveless,” wrote the United Press’s Stan Mockler, “Brecheen has a reputation for having ice water in his veins.”12 After the loss of All-Star Red Munger to the war at midseason, Brecheen (16-5) formed the league’s most formidable quartet of pitchers with Cooper (22-7), Lanier (17-12), and Ted Wilks (17-4); Brecheen’s 2.85 ERA in 189⅓ innings was the highest of the lot. En route to their third consecutive pennant, the Cardinals became the first National League team to record 100 or more victories in three consecutive seasons. As a child, Brecheen had suffered a broken ankle and had a spinal malformation that kept him out of the war with a 4-F classification.

In October the Cardinals and the St. Louis Browns squared off in the Trolley Series with all games played in Sportsman’s Park, which both teams called home, though the park was owned by the Browns. In an unexpectedly competitive World Series that the Cardinals won in six games, Brecheen tossed a complete-game victory in Game Four, winning 5-1. In trouble for most of the game, he yielded nine hits and walked four, but helped himself by recording three assists and one putout.

Brecheen started the 1945 campaign with two complete-game victories, but then came down with a sore elbow which bothered him for the rest of his career. Limited to just 43⅔ mostly ineffective innings by the All-Star break, Brecheen turned his season around in the second half. No longer capable of both starting and relieving because of elbow pain, Brecheen commenced one of the best stretches of his career, completing 11 of 13 starts (with just one relief appearance), winning 12 of 14 decisions, and carving out a microscopic 1.50 ERA in 113⅔ innings. Brecheen, early-season acquisition Red Barrett (21-9 with St. Louis) and rookie Ken Burkhart (18-8) kept the Redbirds in a tight race with the upstart Chicago Cubs, who eventually won the pennant. With a 15-4 record, Brecheen led the senior circuit with a .789 winning percentage and compiled the league’s third-best ERA (2.52).

Brecheen’s success resulted from exceptional control, a deceptive pitching motion, and his knee-buckling curve and screwball. Dizzy Dean was effusive in his praise of Brecheen: “For a little guy, Brecheen gets a lot on the ball. With the kind of control he’s got, he could thread a needle with the ball. He’s the nearest thing to Carl Hubbell. … Hub had a better screwball, but I don’t think he threw that fast.”13 Brecheen would have been a darling to sabermetricians had such advanced metrics existed. For seven straight seasons (1944-1950) he ranked among the top eight NL pitchers allowing the fewest hits and walks (WHIP) per nine innings and the top ten for strikeout-to-walk ratio. “There’s nobody I’ve seen with a finer pitching motion,” said Brooklyn Dodgers star Pete Reiser. “Brecheen hides the ball well and he has fine deception.”14 Not a hard-throwing or overpowering pitcher like contemporaries Ewell Blackwell of the Cincinnati Reds or Kirby Higbe of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Brecheen threw a “sneaky-quick” side-arm fastball that caught batters off guard.15 “Everybody says my screwball is my payoff pitch, but I really don’t use it that often,” Brecheen once revealed. “It just gives the batter one more delivery to worry about.”16

With the conclusion of World War II, the Cardinals anticipated that pitchers Beazley, Murry Dickson, Howie Krist, Munger, and Pollet would be back with team in 1946; consequently, rumors swirled that Brecheen would be traded before Opening Day. However, when Eddie Dyer replaced Billy Southworth as manager of the club in the offseason, Brecheen was reunited with a strong supporter. “I can’t say that I realized that Cat would become the great pitcher he has,” said Dyer, who had a soft spot in his heart for the hurler he brought to the organization.17 The Cardinals broke camp with what Sporting News publisher J.G. Taylor Spink called “the greatest bunch of hurlers ever assembled on one club.”18

The staff led in the NL in ERA for the fourth time in five years, but not all went according to plan. Lanier and Freddie Schmidt jumped to the outlaw Mexican League in late May, Munger’s return was delayed until late August, and Beazley and Burkhart were plagued by arm woes. Brecheen, battling his own chronic elbow pain, pitched consistently all season, often on five or six days’ rest, and finished with a deceptive 15-15 record. A hard-luck loser, Brecheen got three runs or fewer in 14 of those losses (20 runs total). He finished with the league’s fifth best ERA (2.49) and led the loop with five shutouts. Saving his best for last, he tossed a four-hitter to defeat the Chicago Cubs, 4-1, in the next to last game of the season, thereby guaranteeing the Cardinals a share of the pennant.

St. Louis lost the following day to set up a dramatic three-game playoff against the Dodgers. Brecheen came on in relief of road roommate and good friend Dickson with two outs in the ninth inning, protecting an 8-3 lead in Game Two. After surrendering an RBI single and issuing a walk, Brecheen struck out the last two batters to send the Cardinals to the World Series for the fourth time in five years.

Brecheen’s performance in the World Series against the Boston Red Sox was arguably his crowning achievement in the big leagues. In Game Two he hurled a dominating four-hit, 3-0 shutout to even the Series at one game apiece. He struck out four and knocked in the game’s first run with a single in the third inning. With the Cardinals facing elimination in Game Six, Brecheen limited Boston to just one run in a complete-game seven-hitter to earn the win, 4-1, and set up a winner-take-all Game Seven.

Though Brecheen was suffering from a cold, Dyer called on his diminutive lefty one last time. With no outs in the eighth inning and runners on second and third, Brecheen relieved Dickson, who was nursing a 3-1 lead. He set down two batters then yielded a two-run double to Dom DiMaggio that tied the game, 3-3. But then in the bottom of the eighth, in one of the most memorable plays in the annals of the World Series, Enos Slaughter scored from first on Harry Walker’s double with two outs to give the Cardinals a 4-3 lead.

Brecheen, with his customary wad of chaw in his mouth, gave up two singles to lead off the ninth, but then secured the final two outs with runners on the corners, giving St. Louis its third title in five years. “The Cat’s got a head, heart, and guts,” said Dyer after the game.19 With the dramatic victory, Brecheen became the first left-hander to win three games in one World Series, and the first pitcher of any kind to accomplish the feat since Stan Coveleski of the Cleveland Indians in 1920. Mickey Lolich (1968) and Randy Johnson (2001) are the only other left-handers among the 13 pitchers to win three games in one World Series. “Brecheen is a remarkable pitcher,” gushed The Sporting News. “He doesn’t throw hard and his curveball doesn’t break much. But what a gamester he is.”20

With the addition of a “tantalizing slider” to his pitching arsenal, the hero of the ’46 World Series opened the 1947 season with seven consecutive complete games, winning five of them.21 He was named to the first of two All-Star teams, joining Cardinals starters Marion (SS) and Slaughter (LF) and backups Stan Musial (1B), Whitey Kurowski (3B), and Munger. Brecheen pitched the fourth through sixth innings, yielding five hits and one run. Despite persistent elbow pain since early July, Brecheen won his first three starts after the Midsummer Classic to push his record to 12-5. He struggled the last two months to finish with a 16-11 record while the aging Cardinals fell to second place behind their archrivals, the Brooklyn Dodgers.

At the age of 33 and plagued by an elbow that puffed up like a balloon after every start, Brecheen needed some extra time between starts during the cold weather of the early weeks of the 1948 season. He responded to Dyer’s gift by opening the season with three consecutive shutouts, the third of which was his only career one-hitter, a 5-0 victory over the Philadelphia Phillies. He ran his streak of scoreless innings to a personal-best 32 in his fourth consecutive complete-game victory, 8-3. “I can snap off a sharper curve [and] that gives me an effective counter for batters looking for a screwball,” said Brecheen, who added that he was pain-free for the first time in more than four years.22

The Cardinals were in an exciting pennant race with the Dodgers and Boston Braves, but lacked the pitching depth, long the hallmark of the great Cardinals teams, to overtake their competition. Brecheen won 11 of his last 14 decisions en route to a career year for a second-place club. His 20 wins and 21 complete games trailed only Johnny Sain, and the Cat led the NL in ERA (2.24) and shutouts (7) while surrendering only six home runs in a career-high 233⅓ innings. Surprisingly, Brecheen, who was never a big strikeout pitcher, led the NL with 149 punchouts, including two games with a career-high ten. (He had also struck out ten in a game in 1946). He was named to his second and final All-Star Game, joining starters Musial, Slaughter, and Red Schoendienst (2B), but did not pitch.

With the oldest pitching staff in the big leagues in 1949, the Cardinals mounted their last serious challenge for the pennant until 1964. Brecheen (14-11) and Brazle (14-8) were the grizzled veterans at 34 and 35 respectively; Munger (15-8) was 30 and Pollet (20-9) was the youngster at 28. The 34-year-old Brecheen won three of four starts between September 8 and 25 to maintain the Cardinals’ precarious 1½-game lead over the Dodgers and Phillies. But after emerging victorious so often in close games and races, the Cardinals saw their luck run out. They lost their next four games (including one by Brecheen) and needed a victory and a loss by the Dodgers in the last game of the season to set up another playoff with Brooklyn for the pennant. The Dodgers won. Brecheen made a career-high 31 starts and logged over 200 innings for the fourth consecutive and final time in his career.

As the effects of age and ongoing elbow problems took their toll, Brecheen saw increasing duty out of the bullpen during his last three years with the Cardinals (1950-1952). His workload steadily decreased from 163⅓ to 100⅓ innings. In 1950 he posted his first losing record (8-11) as the Cardinals fell into the second division for the first time since 1938.

Brecheen’s value to the Cardinals, however, could not be measured in wins and losses. Always a student of the game, he mentored prospects and veterans alike. “The Cat has a great knack of working with young pitchers and imparting his knowledge,” said Fred Saigh, who purchased the Cardinals from Sam Breadon after the 1947 season.23 In 1952 Eddie Stanky (the Cardinals’ third manager in three years) named Brecheen “pitcher-coach.”24 Considered washed up as a player, Brecheen surprised his skipper and teammates by winning five straight decisions in midsummer, including his 25th and final shutout (a masterful three-hitter against the Cincinnati Reds) as part of a streak of 24 scoreless innings.

Brecheen was involved in a contractual brouhaha after the 1952 season when he signed with the St. Louis Browns on October 30. The Cardinals, who had placed him on waivers at the end of the season, claimed that the Browns had tampered with Brecheen before his official release, and filed a formal complaint with the commissioner’s office, which was eventually dismissed. “[Browns manager Marty] Marion wanted me over here to pitch for him,” said Brecheen. “Eddie [Stanky] is going to concentrate on using his young pitchers next summer so there would be no place on his pitching staff.”25 It was a fortuitous move with long-term consequences. Though he went just 5-13 for a team that lost 100 games, Brecheen was arguably the Browns’ most effective pitcher, posting a staff-best 3.07 ERA in 117⅓ innings. He retired after the season to become the team’s pitching coach.

In his 12-year big-league career, Brecheen established his reputation as a big-game pitcher. “(He) was a real pressure guy,” said Joe Cronin of the Red Sox. “When he walked out onto the field, you knew a ‘take-charge’ guy was in the game.”26 In addition to his brilliance in the World Series, Brecheen compiled a 133-92 record and impressive 2.92 ERA in 1,907⅔ innings in the regular season. He won 114 games and logged 1,715 innings in eight minor-league seasons.

In 1954 the St. Louis Browns were sold and relocated to Baltimore, where they were renamed the Orioles in honor of the city’s team in the International League. While the Browns were arguably the worst team in American League history, the Orioles developed into a model franchise grounded on fundamentals and smart pitching. During Brecheen’s 14-year tenure as pitching coach, the Orioles’ staff ranked in the top four in ERA (the AL expanded from eight to ten teams in 1961) for ten consecutive years (1957-1966) and led the league four times. In an era defined by hard-throwing strikeout pitchers (especially the 1960s), Brecheen preferred fundamentally sound pitchers with good control. He mentored many young pitchers who eventually became All-Stars, including Jim Palmer, Dave McNally, Steve Barber, Chuck Estrada, and Milt Pappas; and also helped seasoned veterans. He converted 36-year-old Hoyt Wilhelm into a starter in 1959 and the knuckleballer promptly led the league in ERA; under the Cat’s guidance, Robin Roberts, considered washed up in 1961, enjoyed a rebirth. In Baltimore’s four-game sweep of the Los Angeles Dodgers in the 1966 World Series, the Orioles yielded just two earned runs in 36 innings.

As he had every offseason throughout his life in baseball, Brecheen returned to Ada with his wife and son, Steve, in retirement. The couple enjoyed traveling throughout the Southwest. An avid hunter and fisherman, Brecheen never lost his passion and interest for baseball. He participated in occasional reunions and old-timer’s games for the Cardinals and Orioles, and was a fixture at local sandlots mentoring youngsters. In 1997 he was inducted into the Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame.

In declining health in his later years, Harry Brecheen died at the age of 89 on January 17, 2004, at a nursing facility in Bethany, Oklahoma. He had been preceded in death by his wife of 63 years, and was buried at Rosedale Cemetery in Ada.

This biography originally appeared in “Van Lingle Mungo: The Man, The Song, The Players” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Newspapers

New York Times

The Sporting News

Online

Ancestry.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

SABR.org

Other

Harry Brecheen player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

Notes

1 Associated Press, San Antonio Light, April 25, 1933, 6A.

2 Bob Broeg, “Keep Your Eye on the Cat,” Sport, October 1947, 32.

3 Broeg, 33.

4 Broeg, 32.

5 The Sporting News, May 8, 1941, 1.

6 The Sporting News, March 26, 1942, 15.

7 The Sporting News, July 1, 1943, 5.

8 Ibid.

9 Broeg, 31.

10 Red Smith, “Views of Sport. The Cat of the Cardinals,” New York Herald Tribune, May 1948 (undated clipping from Brecheen’s Hall of Fame player file).

11 Gene Fehler, When Baseball Was Sill King. Major League Players Remember the 1950s (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012), 232.

12 Stan Mockler, “The ‘Cat’ o’ Nine Innings,” May 1949 (Unattributed article, player’s Hall of Fame file).

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Broeg, 33.

18 The Sporting News, April 18, 1946, 5.

19 The Sporting News, November 6, 1946, 7.

20 The Sporting News, November 20, 1946, 6.

21 The Sporting News, June 4, 1947, 7.

22 The Sporting News, September 22, 1948, 11.

23 The Sporting News, October 3, 1951, 15.

24 The Sporting News, January 30, 1952, 13.

25 The Sporting News, November 5, 1952, 8.

26 The Sporting News, June 6, 1951, 1.

Full Name

Harry David Brecheen

Born

October 14, 1914 at Broken Bow, OK (USA)

Died

January 17, 2004 at Bethany, OK (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.