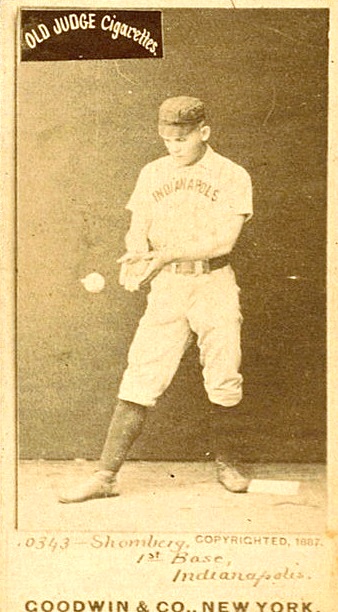

Otto Schomberg

Otto Schomberg was a hitting wonder in his one full year in the big-leagues (1887). Poor fielding and health issues saw him out of the majors after the following season, but the Wisconsin native then became a major-league lumberman with other substantial ventures.

Otto Schomberg was a hitting wonder in his one full year in the big-leagues (1887). Poor fielding and health issues saw him out of the majors after the following season, but the Wisconsin native then became a major-league lumberman with other substantial ventures.

Otto H. Schomberg was born in Milwaukee on November 15, 1864. His father, Henry, (listed as Schoemberg in the 1865 City of Milwaukee Directory) was a cooper, working and living at 710 West Lloyd Street.1

Otto Schomberg first appeared in a City of Milwaukee Directory in 1880 as a laborer, living at 721 7th Street, which was also his father’s address. He was not in the next year’s directory, but appeared in the 1882 and 1883 directories as a machinist.

The young man first appeared in Milwaukee newspapers in 1882, playing first base for the local amateur Arctic Baseball club. In September the club presented their 17-year old first baseman with a gold medal, for being the team member “acquitting himself with the most credit” during the city championship game with the rival Maple Leafs. He also impressed the winning team; the next year Schomberg was playing first base for the Maple Leafs. This strong semi-professional local club played not only local teams but also clubs from other Wisconsin cities and Chicago.

Schomberg was engaged in early 1884 to play first base for the reserve team of the Milwaukee club of the Northwestern League. Clubs in the major leagues and the minor Northwestern League were signing players for these reserve teams to keep as many players as possible out of the hands of the newly formed Union Association. In mid-May the Milwaukee reserve team disbanded. Schomberg had “gained a favorable reputation by his perfect fielding, and [was] in demand.” It was reported the Stillwater (Minnesota) club of the Northwestern League was interested in the well-built lefty, and also that he had been offered $150 a month to play for the Rock Island (Illinois) club. Schomberg turned down the Rock Island offer, preferring to remain in the Northwestern League. The 19-year old signed with Stillwater and played well, “[winning] hosts of friends up there by his fine batting and fielding.” [It must be noted here that Milwaukee newspapers usually spelled Otto’s last name properly — Schomberg — but outside Milwaukee, it was almost always Shomberg].

On August 4, 1884, the Stillwater club disbanded. Conveniently for Schomberg, the Stillwaters had been playing in Milwaukee the previous three days. The Milwaukee Sentinel believed Schomberg was “too good a first baseman and hard hitter to be long without an engagement.” During his time at Stillwater Schomberg had batted .279 (55 for 197) with 14 doubles, 3 triples and 32 runs scored.2 However, he did not play for another minor league club in 1884, again taking over first base for the local Maple Leafs.

For the 1885 season Schomberg accepted a position with the Keokuk (Iowa) club, an alliance club of the Western League. It was reported he would be the first baseman and captain of the team. In June the club joined the Western League, but soon the league disbanded. It was reported that Schomberg went to play at St. Joseph (Missouri).3 However, in August he joined the Leavenworth (Kansas) Reds, where he finished the season.

Schomberg, now considered one of the best left-handed batters in the west, signed with Providence of the Eastern League in 1886, reportedly for $800 for the season. When the Providence team dropped out of the Eastern League in June, Schomberg went to the Utica club in New York. Otto did very well in the International League, leading the batsmen in early July. This caught the attention of “Hustling” Horace Phillips of the Pittsburgh Allegheny club of the American Association, who bought the “splendidly built chap [with] the appearance of a born athlete” for “a good round sum” in early July.

There was no doubt Schomberg was a terrific hitter. Horace Phillips said the 21-year old had the best eye for judging a good ball of any young player he had ever seen, and thought he would turn into a fine big-league hitter by the next season. As opposed to previous accounts, however, it was quickly found that his work in the field was suspect. A report in the Milwaukee Sentinel told of a local player saying that Schomberg was weak on hit balls, and lost his head when he wanted to make an assist. This weakness would soon become more apparent.

When Schomberg came to Pittsburgh, The Sporting News reported that several of the Pittsburgh players spoke highly of his abilities as both a batter and first baseman. Ironically, the one player mentioned by name in the St. Louis weekly was catcher Fred Carroll. In August Schomberg complained that since joining the club Carroll had “acted in a mean manner” toward him. It got so bad at one point that Schomberg thought seriously of asking for his release. When manager Phillips heard of the trouble he asked Schomberg about it, and Otto acknowledged the problems. The Sporting Life told of the events beginning on August 7:

In the meantime someone had informed Carrroll of the inquiries, and he left the supper table and hunted Shomberg up. He found him and accused him of carrying false. This Shomberg denied, and Carroll after applying some language more forcible than polite, hit him. Shomberg immediately retaliated and witnesses say was getting the best of the bout when separated by friends. Phillips immediately suspended Carroll, pending an investigation by the Board of Directors. The Directors met Monday night and revoked the suspension, but fined Fred $50. At this meeting Carroll professed to be very sorry and said that he had struck Shomberg in the heat of passion, and Shomberg and himself shook hands and made it up.

According to The Sporting Life there was more method than madness in Carroll’s remarks, “as the young first baseman began showing evidence of exceeding freshness.” Playing in 72 games for Pittsburgh in 1886, Schomberg hit .272, scored 53 runs and accounted for 29 runs batted in. At first base the 5’ 11”, 175-pounder made 25 errors en route to a .966 fielding average.4

After the season Horace Phillips offered the St. Louis Maroons of the National League Schomberg and $400 for the release of their first baseman, Alex McKinnon. The deal being satisfactory, McKinnon signed with Pittsburgh; at the same time an agent of the St. Louis club signed Schomberg — presumably taking over his $1,800 a year salary. The deal reportedly saved the Maroons $1,500, and the St. Louis management thought Schomberg a better first sacker and a better hitter, who had “a very quiet disposition.” Others agreed, the St. Louis Republican later saying Schomberg could “outplay McKinnon in any department of the game.” Unfortunately, Alex McKinnon never got the time to prove himself, dying of typhoid fever on July 24, 1887.

Schomberg would never get a chance to play in St. Louis. In March 1887 the Maroons were sold to Indianapolis interests for $12,000. Most of the players, including Schomberg, went to Indianapolis.

Otto Schomberg had a terrific year hitting on an awful team. The Hoosiers lost 89 games and only won 37, easily landing in last place. According to the 1887 official National League statistics, Schomberg had a .389 batting average (walks counted as hits in this season), scoring 91 runs. [This has been changed in the record books to a .308 average, separating his 129 hits and 56 walks.] His batting average was eighth best in the league and the best on the Indianapolis team.5 For this accomplishment Schomberg was presented a zylonite ivory bat by the A.G. Spalding & Bros. Company.6

However, Schomberg’s fielding was another story. At first base he committed 55 errors, having only a .958 average, the worst average in the National League for first basemen playing over 100 games. The Sporting Life wrote in September:

Shomberg’s wretched fielding of late has caused much regret. He seems utterly unable to throw a ball across the diamond with any accuracy… Shomberg would be one of the greatest first basemen in the country if he could overcome this one fault. He is a sober, industrious player, and as a batter has but few superiors.

Runners on second base would deliberately break for third when Schomberg had the ball. Hoosier third baseman Jerry Denny was quoted as saying “He can’t throw at all. It is a pity, for Shommy is a great hitter.” Indianapolis President John T. Brush told the press that near the end of the season Schomberg approached him and asked to be played in the outfield. Some of these fielding problems appeared not to be Schomberg’s fault, however. Three years later the St. Louis Globe-Democrat wrote that Denny and Jack Glasscock — the third baseman and shortstop of this 1887 team — were “unquestionably the rankest throwers in the business…they literally killed the prospects of Otto Shomberg.” The paper reported the two threw so savagely to first base that accuracy was out of the question.

Even with these well-known defensive liabilities Schomberg was in demand. In June Al Reach of the Philadelphia National League club tried in vain to induce the Indianapolis directors to sell Schomberg’s rights to him. After the season it was still being reported the Philadelphia club wanted to get him.

But Otto Schomberg had bigger troubles to worry about than poor fielding. In October it was reported that his old trouble, heart disease, was growing worse every day. At least three times during the season he had to take off because of this problem. The report stated: “He is thinking seriously of quitting the business. All the players advise him to do so, as they believe he will some day drop dead on the field.” However, a report in The Sporting Life in January 1888 stated that Otto told a friend he had fully recovered from this heart trouble and was in splendid health.

Schomberg held off signing his 1888 contract with Indianapolis, reportedly wanting a raise to $2,500. However, the Indianapolis correspondent to The Sporting News said the difference between what the player wanted and the club was offering was “quite insignificant and easily adjusted.” Schomberg finally signed in late March. The new season found him in right field, with newly acquired Tom “Dude” Esterbrook at first base. It appears his fielding was not much better in the outfield, as he would be charged with three errors to go with 15 putouts and three assists — for a miserable .857 average. On May 2 Schomberg severely sprained his ankle sliding into second base and had to be carried off the field. This injury kept him out of the lineup for about five weeks. He returned as the club’s right fielder, but soon went back to first base, as Esterbrook was out of the lineup, not hitting much.

While Shommy had been out with this injury, a rumor was about that Indianapolis would release him to Pittsburgh. The Hoosiers’ manager, Harrison Spence, said there were no such plans. He went further, saying the Indianapolis management had an idea of making a pitcher out of Otto. “He exhibits terrific speed, and has one or two good curves.” This did not come about.

Within weeks of rejoining the team Schomberg was out again, this time with malaria. He did come back, but by this time Esterbrook was back at first base and there was no room for Schomberg. On August 17 the Hoosiers signed first baseman Lewis “Jumbo” Schoeneck; they released both Schomberg and Esterbrook, who were expendable. Otto had hit only .214 in the 30 games he played. He returned to Milwaukee and played first base for the amateur Milwaukee Browns.

Otto Schomberg was out of big-league baseball — but getting into the major leagues in the lumber business. In the late 1870s his brother, Henry, along with another man, had bought a lumber operation in the Grand Traverse Bay district of Michigan, with offices in Good Harbor. Shortly after 1880 Henry bought out his partner; later in the decade (no later than 1886) he sold the business to his brothers Otto and Richard. At first Richard managed the operations in Good Harbor. Otto stayed in Milwaukee to handle sales and supplies for the mill and company store at offices in the Marine Block on Ferry Street at Seeboth.

As early as February 1887, off-season reports told of Otto doing well at the business in Good Harbor. The Milwaukee Sentinel of February 10, 1887, told its readers “he had a great head. Some of the other players would do well to follow his example.” By the end of 1887 Schomberg was not only attending to the lumber business in Good Harbor but also acting as the city’s postmaster. He also wanted it known he was making baseball bats, and was expecting to get out 5,000 first-class second-growth ash sticks. The Milwaukee Sentinel of January 23, 1888, gave this detailed report on the local success story:

Shomberg is one of the few players who does not depend upon ball playing for a living. He is the junior member of the firm of Henry Shomberg & Bro., manufacturers of hardwood lumber and cooper’s stock, at Good Harbor, Mich. He writes that he is at present attending to the log scaling of his business and has charge of a gang of 150 men. His firm is doing an immense business and his father and brother are opposed to his going back to Indianapolis in the spring. But he says he wants to play just one more season and show the country what he can do. His physician ordered him to quit using tobacco and assures him that he will never again experience any trouble with his heart, if he leaves tobacco alone. He proposes to follow his physician’s advice and feels confident that he will lead the league in batting.

In February 1889 Schomberg let it be known he would like to cover first base for the Milwaukee team of the Western Association, but the Brewers were satisfied with their first sacker, Tom Morrissey. By the next month Schomberg was saying he would not play ball that season, as he could not afford to neglect his business. However in May he was persuaded to cover first base and captain a new professional team. Milwaukee businessman Rudolph Giljohan organized a club known as the Cream Citys. They played other strong teams that were not in any league, from the area and from as far away as Chicago and Oshkosh. They had a successful season, playing through October.

Schomberg’s baseball career was not over just yet. In June of 1890 he umpired a Northwestern League game in Milwaukee when the regular ump refused to serve any longer after an argument on a disputed call. Otto also played a bit as the Cream Citys first baseman when that club re-formed in June. Later that summer he was the captain and first baseman for the South Side Club of Racine “in an old fashioned game for blood” in that city. A little later the 25-year-old former major-leaguer played with the Belle City Club of Racine in a few games.

1890 marked the end of Otto Schomberg’s playing days, but not his association with baseball in Milwaukee. In 1891 he umpired a Western Association game in Milwaukee, and one more in both 1892 and 1894. In May 1895 the regular umpire failed to show for the scheduled Western League game in Milwaukee and Schomberg officiated. “He was off on balls and strikes in the early part of the game,” the Milwaukee Journal reported. Schomberg umpired another Western League game in June.

In October 1893 it was announced that Otto Schomberg would be the president of the Milwaukee Western League club being organized for the next season. The Milwaukee Sentinel gave the club’s reasons for picking Schomberg: “He was decided upon as an available man on account of his familiarity with baseball, his large acquaintance in the city and his ability to work unceasingly in any enterprise in which he is engaged.” He also owned $400 worth of stock in the incorporated $4,000 franchise. However, within weeks Schomberg resigned, stating that his business engagements for the coming summer made it impossible for him to serve the club in the capacity of president.

The last time Otto Schomberg’s name appeared in the press in connection with baseball was in January 1898. The Milwaukee Sentinel reported that the 33-year old Schomberg had announced his intention to return to the diamond, and offered to play first base for the Brewers should a vacancy occur. When Otto returned from his business interests in Michigan he wrote the newspaper he had no intention of returning to the field. In his words: “The baseball business is all right, but I like the lumber business better.”

By the time that he was chosen as president of the Brewers in late 1893, Schomberg was regarded as “a substantial business man.” In 1894 he went into partnership with two other local lumbermen, Charles and Fred Tegge, under the firm name of Schomberg & Tegge, with yards at 684 Park (today’s West Bruce Street, west of 14th Street). The following year Schomberg & Tegge consolidated with the Page & Landeck Lumber Company. Otto Schomberg was now the general manager of the largest hardwood firm in Milwaukee. In November 1896, Richard, Otto, and his wife Ida Schomberg incorporated the company under the name Schomberg Hardwood Lumber Company, with $15,000 in capital. At its peak the mill in Michigan cut 8,000,000 board feet of lumber per year. The company also ran a hotel, two stores and a saloon in Good Harbor.

Schomberg’s acumen was shown by his novel store promotion. Otto would buy merchandise at bankruptcy or fire sales — for example, a lot of 500 derby hats — and offer them as premiums. Customers who bought at least $10 of goods got a hat. They became quite a hit and all the men in the area were wearing them.

At home Otto was also very busy, within and outside the lumber business. In 1892 he purchased a half-interest in the schooner Hattie Earl, which he enjoyed sailing on Lake Michigan. Later that year, in November, heg married Ida Carter of Milwaukee, and the two built a home the following year at 1213 2nd Street.

Schomberg was also a stockholder in the West Side Bank and a delegate at the Republican congressional convention from the city’s 21st Ward in 1896. The Schombergs were also active in Milwaukee society, Otto being a member of the Bon Ton club, the North Side Literary club and the Millioke club. The latter was a north side social organization boasting to be “a society that will have among its members the better class of its portion of Milwaukee residents, and whose functions shall be affairs in local social circles.” Mrs. Schomberg was active in the Women’s School Alliance and the Social Culture club.

As “elite” as all these clubs and organizations may sound, Schomberg still had a sense of community. In 1898 the Twenty-First District school became the home for night classes of the Manual Training School. Schomberg, along with other businessmen, helped with the cost of outfitting the school.

After 1900 the lumber supply at Good Harbor was decreasing. The end came for the Schombergs in Michigan in 1905 when the yard burned, destroying the mill and about one million feet of lumber. Schomberg sold the mill and the remaining buildings to an employee for $475.

After leaving his Michigan holdings, Otto remained in the lumber business in Milwaukee, became treasurer of the National Leather Goods Company, and dealt in real estate. In 1905 he built the four-story Schomberg Building at 549 North 4th Street. This $36,000 brick building had stores on the ground floor — including office space for the Schomberg Hardwood Company — and apartments on the remaining three floors. [In 1916 this building was turned into the Hotel Delaware.] In 1915, Schomberg built three “beautiful houses” featuring English exterior design at 2723, 2727 and 2729 East Belleview. They were rental property.

In his later years Schomberg built new homes for himself in Milwaukee — 2575 North Lake Drive (1912) and 2757 North Summit (1922)7 — in addition to having a winter home in California. Traveling to California he was able to scout some talent and keep in touch with his old acquaintance Connie Mack of the Philadelphia Athletics, as some letters in the collections of the Milwaukee County Historical Society show.8 Otto Schomberg was also an intimate friend of Milwaukee Brewers owner Otto Borchert.

For the last two years of his life Schomberg was in ill health. While returning from his winter home in California with his wife on a Santa Fe train, Schomberg died of a heart attack in his compartment on May 3, 1927, outside of Ottawa, Kansas. Otto Schomberg was laid to rest at Milwaukee’s Fairview Mausoleum. He was survived by his wife Ida, a son and a daughter.9

Sources

Milwaukee Sentinel, various issues 1882-1898

Milwaukee Journal, various issues 1884-1897, 1915, May 4, 1927

Boston Daily Advertiser, February 23, 1886

Chicago Daily Inter Ocean, various issues 1887-1888

Rocky Mountain News, various issues 1885-1888

St. Louis Globe-Democrat, various issues 1886

St. Paul Globe, August 4, 1884

The Sporting Life, various issues 1885-1888

The Sporting News, various issues 1886-1888

Yenowine’s Illustrated News, various issues 1890 and 1892

City of Milwaukee Directories, 1860 through 1916

National Park Service web site (http://www.nps.gov/slbe/historyculture/goodharbor.htm)

Notes

1 Date of birth taken from Schomberg’s death certificate (a copy provided by the Baseball Hall of Fame). All other references — going back to The Official Encyclopedia of Baseball, Yurkin and Thompson, 1971; and The Baseball Encyclopedia, MacMillan 1974 — state he was born Otto Shambrick on November 14, 1864. No Shambrick is listed in the City of Milwaukee Directories from 1859 on. The Milwaukee County birth records index does not list a Shambrick, Schomberg, or Shomberg having been born in the years 1860 to 1868. The death certificate lists Otto’s father as Henry Schomberg, and makes no mention of the name Shambrick.

2 Personal communication from James Cagley of the Minnesota Historical Society

3 SABR member Mike Welsh took the time to go through the St. Joseph Evening News from June 1, 1885 to August 15, 1885, and could find no reference to Shomberg or Schomberg.

4 Statistics from baseball-reference.com

5 Chicago Daily Inter Ocean, October 22, 1887; baseball-reference.com

6 Historical Messenger of Milwaukee County Historical Society, September 1968.

7 McArthur, Shirley du Fresne. North Point Historic Districts-Milwaukee. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: 1981: 135, 196; Historic Designation Study Report-Epiphany Lutheran Church, date unknown.

8 Historical Messenger of Milwaukee County Historical Society, September 1968

9 Milwaukee Sentinel, May 6, 1927; Otto Schomberg’s death certificate.

Full Name

Otto H. Schomberg

Born

November 14, 1864 at Milwaukee, WI (USA)

Died

May 3, 1927 at Ottawa, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.