Firpo Marberry

Fred Marberry, one of the best pitchers in baseball for a decade, was the first great hurler to be used primarily as a relief pitcher. He played a large role in Washington’s only World Series triumph, and set many records for relievers that would not be bested for many years. Almost forgotten today, he has been denied larger fame by splitting his career between starting and relieving —had he done one or the other, he might be in baseball’s Hall of Fame today.

Fred Marberry, one of the best pitchers in baseball for a decade, was the first great hurler to be used primarily as a relief pitcher. He played a large role in Washington’s only World Series triumph, and set many records for relievers that would not be bested for many years. Almost forgotten today, he has been denied larger fame by splitting his career between starting and relieving —had he done one or the other, he might be in baseball’s Hall of Fame today.

Frederick Marberry was born on November 30, 1898, on a farm near Streetman, Texas, about 75 miles south of Dallas. His parents, Levi and the former Nancy Bogard, were both natives of Mississippi who migrated westward in the 1880s. Fred was the 10th of 12 children, five of whom died young, before Fred was born. The other seven Marberry children each lived at least 70 years.

Marberry apparently played little baseball as a youngster, spending most of his after-school hours working on the family farm. As a teenager he joined the Streetman town team, usually playing the infield. He was not asked to pitch until 1920, when he was 21 years old and had attained all of his height of 6-feet-1, though not his eventual 210-pound frame.

Marberry had no finesse on the pitcher’s mound. He threw nothing but fastballs, but threw hard enough to earn a contract in 1922 with Mexia, a town 20 miles to the south that played in the Texas-Oklahoma League. He pitched 25 games there (7-11, 2.82) before moving on to Jackson of the Cotton States League (2-2, 3.60), and Little Rock of the Class A Southern Association (0-4, 3.41). He pitched well enough to earn a return trip in 1923 to Little Rock, where he was 11-10 with a 3.50 ERA.

Legendary Washington Senators scout Joe Engel heard enough about Marberry to go to Arkansas to have a look, and he soon signed the big right-hander, bringing him to Washington in early August 1923. For the Senators, Marberry finished 4-0 in 11 games with a 2.80 ERA. He was 24 years old, still having pitched for a only few years.

Early on in Washington, Marberry acquired the nickname Firpo because of his size and facial resemblance to Argentine boxer Luis Firpo. The fighter, dubbed “The Wild Bull of the Pampas,” knocked Jack Dempsey out of the ring in a 1923 title bout before losing in the second round. Marberry never liked the nickname, especially as Luis Firpo’s career fizzled out, but he would be Firpo Marberry for the remainder of his baseball years.

One of the more interesting stories on the 1923 Senators was Allan Russell, previously a pitcher for several years with the Boston Red Sox and New York Yankees, and one of the few pitchers still allowed to throw a spitball. Manager Donie Bush (likely with the urging of Clark Griffith) turned Russell into one of the first full-time relief specialists. He started five games, relieved in 47 (a new record), finished 10-7, and “saved” nine games. (Saves were not recorded in 1923, but were retroactively figured in the 1960s.) Of his 181 innings pitched, 144 came in relief (also a new record), meaning he pitched an average of three innings every time he came in as a reliever. This may have been the best season ever put forth by a relief pitcher up until this time.

Marberry began the 1924 season as an extra starter and as a second reliever to Russell. When the latter hurler struggled to repeat his 1923 success, new Senators manager Bucky Harris turned to Marberry more and more often. He responded sensationally. He pitched in 50 games, 35 in relief, won 11, saved 15 and pitched 195 innings, fourth most on the team. Harris used Marberry as Bush had used Russell the previous year: an average of three innings per appearance and as early as the second inning if needed. Russell finished second in the league with eight saves, and the Senators set an all-time team record with 25.

The Senators won their first American League pennant in 1924, and the Browns’ George Sisler, among others, thought Marberry was Washington’s MVP. In the second game of the World Series, he came into a tie game with two outs in the ninth inning to strike out Travis Jackson, and then watched as the Senators won the game in the bottom of the ninth. By modern reckoning he would be awarded the victory, but the official scorer awarded the win to starting pitcher Tom Zachary. Marberry started and lost Game Three, but pitched well in Games Four and Seven as the Senators captured their first and only World Series title.

At the time, games at Griffith Stadium typically started at 4:00. In the faster-paced games of the time, this meant that “Marberry Time,” as it was soon called, would arrive at about 5:30 or 6:00, with the shadows rolling across the diamond. For a fastball pitcher like Marberry, this was an ideal environment.

Marberry cut quite the figure when he entered a game. Teammate Al Schacht recalled: “Sometimes Bucky would go to the pitcher’s mound just to talk to the pitcher, unsure about whether to take him out. But he’d no sooner get to the mound, and there would be Marberry —out of the bullpen coming in.”1 Ossie Bluege remembered: “You should have seen Fred walk across the outfield when he was coming in to relieve. He moved just as fast as he could and just as determined and as confident as could be.”2

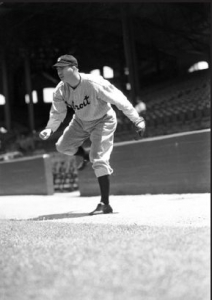

A big man for his time, Marberry stomped around the mound, throwing and kicking dirt, glaring angrily at the batter. He relied on no fancy stuff —he basically just reared back with a high leg kick, and fired the ball to the catcher. When Marberry warmed up between innings, catcher Muddy Ruel caught every pitch in the center of his glove to maximize the noise of his fastball. Along with the sound that could be heard in the opposing dugout, Ruel allowed himself to stagger as each pitch hit his glove.

Washington won the pennant again in 1925, with Marberry playing another large role. This time he was used exclusively as a relief pitcher, setting records with 55 relief appearances and 39 games finished. Marberry pitched only twice in the World Series, and Harris received some criticism for this. In the seventh and deciding game, while a rested Marberry watched, Walter Johnson was allowed to give up 15 hits and 9 runs in a complete-game 9-7 loss.

In 1926 Marberry appeared in 64 contests, extending his relief appearances record to 59. Although not calculated until decades later, he also earned 22 saves, a record that would not be surpassed until Joe Page did so in 1949. Though still effective, Marberry regressed a bit in 1927 (10-7, 4.64) and 1928 (13-13, 3.85), pitching mainly in relief but getting 21 starts over the two seasons.

After the 1928 season, Walter Johnson, who had retired as a pitcher a year earlier, replaced Bucky Harris as manager. Johnson used Marberry both to start and to relieve, and Marberry responded with a 19-12 record (16-8 as a starter) and 11 saves (the most in the league), starting 26 of his 49 games. He logged 250 innings, and his 3.06 ERA was second in the league to Lefty Grove.

Marberry had become enamored of a starting role: “Relief pitching is a job for a young pitcher. His arm can stand the wear and tear of uncertain work. … In my own case, I feel that I have earned the right to a change.”3 He was used in this dual role for the next two years, resulting in records of 15-5 (15-2 as a starter) and 16-4 (13-3 when starting), yet still hurling 34 games in relief over the two seasons.

Although he still had a good fastball, Marberry began using a curveball and changeup in midcareer, which made him all the more effective. In 1932 Johnson used him mainly out of the bullpen again (15 starts and 39 relief outings), and Marberry responded with another excellent season: 8-4 and a league-leading 13 saves.

After the 1932 season, Johnson was fired, and the 34-year-old Marberry was traded with Carl Fischer to the Tigers for pitcher Earl Whitehill. The Tigers skipper, old friend Bucky Harris, used Marberry almost completely as a starter (32 starts and 5 relief appearances), and he finished 16-11 with a 3.29 ERA (fifth best in the league). In 1934 Mickey Cochrane replaced Harris and moved Marberry back to his dual role. He again finished with a solid record: 15-5 in 38 games. Detroit won the American League pennant, but Marberry was hit hard in his only appearance (1⅔ innings, five hits, four runs) in the Series, which the Tigers lost.

After just five games in 1935, Marberry developed a sore arm that led to his release on June 11. Oddly, he was offered and accepted a job as an American League umpire, with no minor-league apprenticeship. He lasted only a short time. “It’s too lonely for me. I like to be around the players and have companionship.”4

In 1936 Marberry accepted a tryout with the New York Giants. Believing that the problem causing his sore arm was his teeth, he had 14 abscessed teeth extracted. Nonetheless, he pitched in only one game for the Giants before being released. He then had a brief return to the Senators (Bucky Harris was managing again), pitching in five games, before leaving the major leagues for good.

Marberry was not done pitching, by any means. He went back to Texas, hooking on that same year with Dallas of the Texas League, compiling a 12-3 record and pacing the circuit with a 2.12 ERA. In 1937 he was 11-4 for Dallas, even managing for a while, before signing on with Toledo of the higher American Association. He finished 7-2 for the Mud Hens, leaving him 18-6 for the season.

In 1939 Marberry began with Toledo again, but after just 14 games, and a 4-7 record, he returned to the Texas League, this time with Forth Worth. He finished the 1939 season with the Cats, and also pitched the next two full seasons for them before drawing his release early in the 1941 campaign. His professional career was finally over at age 42.

Marberry had married the former Mattie Louise Womack on March 11, 1923, and the couple had two children: Peggy Ann, born in 1932, and Fred Jr., born in 1937. The family owned a 600-acre farm near Marberry ‘s boyhood home in Mexia. After his baseball days, he operated a wholesale gas distributorship and, later, ran a recreation center in Waco.

In October 1949 Marberry was in a serious automobile accident in Mexia in which he lost his left arm. The injury did not noticeably slow him down —he even continued to pitch in old-timer’s games. He suffered a stroke and died on June 30, 1976, in Mexia, and was interred there in Bindston Cemetery.

Fred Marberry was a great pitcher in two roles. In 187 starts, he managed a record of 95-51; had he packed these starts into five seasons, 37 starts per year, he would have averaged a 19-10 record. As a reliever, Fred held the single-season (22) and career (101) save records for many years. Since he did both things so well, his managers were never able to stick him in one role and leave him there —he was too valuable to assume a consistent role. Had he started or relieved his entire career, he would likely be one of the more famous players of his era. Either way, he was an outstanding pitcher, and the first of the great relievers.

Sources

Blaisdell, Lowell B., “Marberry, Frederick ‘Firpo,’” Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball. Ed. David L. Porter. (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000).

Frederick Marberry file at National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York.

Hillman, J.R., “Pioneer Relief Pitcher, Firpo Marberry.” Sports Collectors Digest, May 10, 1996.

Thomas, Henry W., Walter Johnson: Baseball’s Big Train (Washington, D.C.: Phenom Press, 1995).

Thorn, John, The Relief Pitcher: Baseball’s New Hero (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1979).

Notes

1 Henry W. Thomas, Walter Johnson: Baseball’s Big Train (Washington, D.C.: Phenom Press, 1995), 187.

2 Thomas, Walter Johnson, 187-88.

3 John Thorn, The Relief Pitcher: Baseball’s New Hero (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1979), 56.

4 Thorn, The Relief Pitcher, 57.

Full Name

Frederick Marberry

Born

November 30, 1898 at Streetman, TX (USA)

Died

June 30, 1976 at Mexia, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.