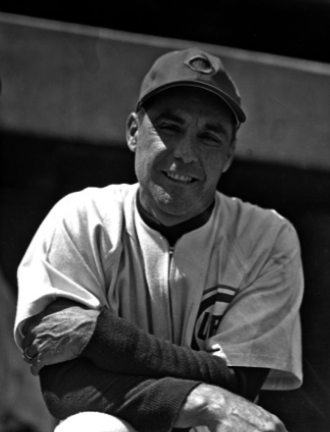

Phil Cavarretta

In 1934, at the height of the Great Depression, 17-year-old Phil Cavarretta helped support his family by playing professional baseball in the Chicago Cubs organization. At the end of his first and only season in the minor leagues, the Chicago native made his first start in the big leagues two months after his 18th birthday and hit a game-winning home run at Wrigley Field, three miles from his boyhood home and high school. For the next 19 years the first baseman/outfielder was a mainstay of the Cubs. A four-time All Star, he won an MVP Award and a batting title, played in three World Series, and was a player/manager for two-plus seasons. His competitive spirit and relentless hustle made him one of the all-time favorite Cubs players. He was, as many have said, “Mr. Cub” before that title was bestowed upon Ernie Banks.

In 1934, at the height of the Great Depression, 17-year-old Phil Cavarretta helped support his family by playing professional baseball in the Chicago Cubs organization. At the end of his first and only season in the minor leagues, the Chicago native made his first start in the big leagues two months after his 18th birthday and hit a game-winning home run at Wrigley Field, three miles from his boyhood home and high school. For the next 19 years the first baseman/outfielder was a mainstay of the Cubs. A four-time All Star, he won an MVP Award and a batting title, played in three World Series, and was a player/manager for two-plus seasons. His competitive spirit and relentless hustle made him one of the all-time favorite Cubs players. He was, as many have said, “Mr. Cub” before that title was bestowed upon Ernie Banks.

Before signing with the Cubs, the left-hander had been a star pitcher and first baseman for Lane Tech High School’s 1933 city championship team and then had led his American Legion team to a national championship later that summer. “I always loved baseball,” said Cavarretta in a 2001 interview, “even in grade school.” (As a youngster he would earn free passes to Wrigley Field by helping clean up the park after a game ended; when that opportunity wasn’t available, he would sneak in.) “I started by playing 16-inch softball. That was a pretty big target and I wish I was hitting that when I played in the big leagues.”1 But the effects of the Great Depression quickly turned the teenager playing for the love of the game into a professional trying to earn a living.

Philip Joseph Cavarretta was born in Chicago on July 19, 1916, the third child of Joseph and Angela Cavarretta, immigrants from Palermo, Sicily. His older siblings were Michael and Sarah. “All we spoke at home was Italian,” said Cavarretta. “I learned English at school.” The family was hit hard by the Depression. “We had a tough time getting anything to eat,” he recalled. “My dad (who had lost his job as a school janitor) couldn’t get a job, my brother couldn’t get a job. Things were so tough I’d go down to the coalyards and pick up the droppings from the coal cars and take them home to put in the pot-bellied stove.”

When he told Percy Moore, his high school and American Legion coach, that he would have to drop out of school to help support the family, Moore arranged for his young star to have a tryout with the Cubs. The high school senior was not greeted with open arms when he showed up at Wrigley Field in the spring of 1934. “I went out there and I must have weighed all of about 150 pounds,” he said. “I’m walking around and, geez, all these players are looking at me and they thought I was a batboy. Someone came up and said, ‘Hey, kid, what are you doing here?’ and I said, ‘I’m here for a tryout.’ (Cubs pitcher) Pat Malone, he was a tough guy, he came up and said, ‘A tryout? You oughta go get something to eat and put some weight on, kid.’ I was scared to death.

“Finally, Charlie Grimm, the Cubs first baseman and manager, came over and said, ‘Go get yourself a bat, take a few swings and we’ll look at you.’ Anyway, I had a real good batting session. One I hit out of the park. They were saying, ‘Look at this guy, he’s whacking that pea pretty good. We’d better sign this kid.’ ”

The Cubs did sign the kid, for $125 a month. Cavarretta’s father had not always been fond of his son’s love of baseball, a game he considered a frivolous waste of time. But his objections disappeared when he saw what his son would be making as a professional ballplayer.

Initially Cavarretta was assigned to the Peoria Tractors in the Class B Central League. In his first professional game, on May 15, 1934, he hit for the cycle and drove in four runs. When that league folded after Cavarretta had appeared in 23 games, he was sent to the Reading Red Sox in the Class A New York-Pennsylvania League.

After hitting .310 in 108 games in the minors, Cavarretta was called up in mid-September while the Cubs were in Boston to play the Bees. After two hitless pinch-hitting appearances on the road, he made his first start in front of hometown fans at Wrigley Field on September 25. In the second inning, the 18-year-old rookie hit a homer off Reds pitcher Whitey Wistert for the only run in a 1-0 win. He then started at first base in the Cubs’ remaining four games, going 8-for-17.

Three games into the 1935 season, Grimm, who had been the Cubs’ first baseman for nine years, turned the job over to Cavarretta, who went on to start 145 games. On September 25 the one-year anniversary of his first big-league home run, he again hit a second-inning homer that provided the only run in a 1-0 win, this time over the second-place Cardinals. That victory, the 19th straight for the Cubs, clinched at least a tie for the pennant. In the Cubs’ six-game World Series loss to the Tigers, Cavarretta played every inning but managed only three singles in 24 at-bats.

Grimm would later claim credit for creating the nickname that would stick with Cavarretta the rest of his career. “When I first saw Cavarretta in the mid-‘30s, I started calling him ‘Philibuck,’” said Grimm. “It just came to me and was inspired, if you can call it that, by my reaction that here was a hard-nosed athlete. Phil liked it.”2 According to Len Merullo, the Cubs shortstop from 1942 to ’47, he and Cavarretta, his road roommate, shared a different nickname. “We were two Italian kids, about the same age and we got along great,” said Merullo. “Our teammates called us ‘The Grand Opera Twins.’”3

Cavarretta was again the starting first baseman in 1936, but in 1937 and ’38 he played primarily in the outfield, the Cubs having acquired veteran Rip Collins. In 1935 Cavarretta had led the NL in errors by a first baseman, and would again in 1943. Grimm later said, “We moved him off first a couple of times and put him in the outfield when we got such experienced first basemen as Rip Collins and Babe Dahlgren. But Phil gradually mastered the position.”4 The Cubs again won the pennant in 1938 but were swept in the World Series by the Yankees, in spite of Cavarretta’s .462 batting performance.

Injuries in 1939 and 1940 limited Cavarretta’s playing time to 22 and 65 games respectively. On May 8, 1939, he broke an ankle sliding into second base. He returned on July 25, but appeared in only seven more games. The following season Cavarretta broke the same ankle, again sliding into second, again against the Giants. According to The Sporting News, the injury occurred during the July 16 game, before Cavarretta drove in both runs in a 2-0 win. The next day Cavarretta scored the Cubs’ only run in a loss to the Dodgers. It was not until July 18 that x-rays revealed the injury.5

In 1944 Cavarretta, who was exempt from military service because of a perforated eardrum, earned the first of four consecutive All-Star selections. (In the 1944 game he set an All-Star Game record by reaching base five consecutive times, on a triple, single, and three walks.) Playing in all but two games that season, he batted .321, fifth in the NL, and tied Stan Musial for the league lead in hits with 197.

The next year Cavarretta reached the pinnacle of his career, leading the Cubs to their third pennant in 11 years with a league-best batting average (.355) and on-base percentage (.449) while driving in a career-high 97 runs. In the Cubs’ seven-game World Series loss to the Tigers he hit .423, with two doubles, one home run, seven runs scored, and five RBIs. Then, in November, he was voted the league’s Most Valuable Player by a wide margin. “It was the kind of a year you dream of,” said Cavarretta. “Everything has to go your way, your line drives have to drop, your broken-bat hits have to drop.”

The Cubs finished third in 1946 before descending into what would become a long stay in the second division. On July 21, 1951, two days after his 34th birthday, the 18-year veteran was named the player/manager of the seventh-place Cubs, replacing Frankie Frisch. The team went 27-47 under their new manager and finished in the cellar.

In 1952 Cavarretta became the first Italian American to manage a major-league club for a full season. That year the Cubs moved up to fifth place with a 77-77 record, their only non-losing record between 1947 and 1962. When I asked him, in 2001, if he was aware of this distinction, the 84-year-old Cavarretta said, “I feel honored. I didn’t know that. That’s great.”6

After the Cubs fell back to seventh place in 1953, Cavarretta’s tenure as manager came to an abrupt end the following spring. On March 29, 1954, within a few days of telling owner Phil Wrigley that the Cubs would probably finish in the second division, Cavarretta became the first manager ever fired during spring training. The dismissal was all the more bitter for him since it came after an exhibition game in Dallas, where at the time he made his home and owned a children’s amusement park.

Wrigley was quoted as saying, “I decided to remove Cav as manager when I learned that he picked everyone else but us to finish in the first division. I did not feel the picture was as bleak as he painted it.”7 However, nearly 50 years later Cavarretta remained convinced that it was the Cubs’ general manager, Wid Matthews, who persuaded Wrigley to dismiss him. “I guess my general manager got to Mr. Wrigley and he (Matthews) didn’t like what I said,” Cavarretta explained in 2001. “We didn’t get along together. I was just being honest with Mr. Wrigley, telling him the truth. Before the meeting was over, Mr. Wrigley said, ‘This is the first time in all the time I’ve owned the club that any manager has spoken to me on these grounds. I’m really glad that we talked.’ I felt pretty good.”

Soon after, Cavarretta was summoned by Matthews. “I figured we were going to go over the roster and see who we were going to keep and who we were going to release. Well,” said Cavarretta with a chuckle, “he released me. I couldn’t believe it.” Wrigley appointed Stan Hack, manager of the Cubs’ Pacific Coast League team in Los Angeles, to replace Cavarretta, then asked Cavarretta to replace Hack in Los Angeles. When Cavarretta declined, his 20-year career with the Cubs was over. His tenure as a Cubs player is surpassed in franchise history only by Cap Anson’s 22 years.

In a story about Stan Hack’s first day as Cavarretta’s replacement, the Chicago Tribune casually announced that “the Cubs yesterday officially retired Phil Cavarretta’s No. 44.”8 For reasons that remain unclear, there never was a formal ceremony to retire the number.9

In a column for mlb.com posted on December 24, 2010, former baseball executive Fred Claire suggested that the time had come for the Cubs to formally retire Cavarretta’s number. “Phil Cavarretta gave his heart and soul for 20 years to the Chicago Cubs,” he wrote. “It seems as though it’s time for the Cubs to give the Cavarretta family the honor it deserves by retiring No. 44. It might even be a nice omen for a team trying to get back to a World Series for the first time since a young man wearing No. 44 was playing first base.”10

Both Claire and Cubs historian Ed Hartig have noted that even though the number was never officially retired, thanks to longtime Cubs clubhouse man Yosh Kawano no Cubs player wore number 44 until the team signed Burt Hooton in 1971. Claire quoted former Cubs manager Joey Amalfitano as saying, “Yosh didn’t want the uniform used because he felt it should have been retired. It was kind of an unofficial retirement of a uniform in honor of Phil.”11

After being fired, the 37-year-old veteran moved across town to play for the White Sox, hitting .316 in 71 games. His playing career came to an end on May 9, 1955, when the White Sox released him after he had appeared in six games.

At 5-feet-11-inches tall and 175 pounds, Cavarretta was hardly the prototypical slugging corner infielder. In 6,754 at-bats he hit 95 home runs (one every 71 at-bats) with a .416 slugging percentage. But he was a solid contact hitter, with a lifetime average of .293 and a .372 on-base percentage. “I was a disciplined, patient hitter,” he said. His .355 batting average in 1945 remains as of 2014 the Cubs’ single-season record for a left-handed hitter, and he ranks in the top ten in franchise history in runs, hits, RBIs, extra-base hits, triples, and walks.

Van Lingle Mungo was the victim of Cavarretta’s sixth career home run on July 22, 1935, at Ebbets Field. Cavarretta’s solo shot in the bottom of the tenth tied the score at 13-13 (Mungo had come on in relief in the eighth inning), but the Dodgers scored in the top of the 11th to win, 14-13. According to Cavarretta’s son, Phil Jr., his father did not have fond memories of Mungo, who drilled him with a pitch in his first full season with the Cubs. “When he got back to the bench,” said Phil Jr., “he expressed his frustration with Mungo to pitcher Charlie Root. ‘Don’t let it bother you,’ said Root. ‘Nobody really likes the guy. I’ll get him for you later.’”12

With his boundless energy, constant hustle, and competitive fire, Cavarretta captured the hearts of Cubs fans. The Cubs’ 1941 yearbook described him as “slim, swarthy, easy-going off the field, but possessed of one of the most fiery competitive temperaments in baseball.” In a 1945 article in The Sporting News, Edgar Munzel wrote: “Phil definitely is a throw-back to the rugged hell-for-leather days. To him the opposition is the enemy and no quarter is asked and none given.” The article quoted Cavarretta as saying: “Hustling was just born in me, I guess. By hustling you look good, you make your ball club look good and you make the fans feel like they’re really getting their money’s worth.”13

It was during the 1938 World Series against the Yankees that Cavarretta got the chance to meet his boyhood hero, Lou Gehrig. “I got on base, I think it was the third game,” he recalled. “He’s holding me on first and I’m peeking at him, thinking, ‘My God, this is my man.’ He finally said, ‘I’ve been watching you and I like the way you play. You’re always hustling.’ Then he said one more thing, and I’ll never forget this as long as I live. He said, ‘Don’t change.’ The rest of my career I always remembered that because I always gave one hundred percent, I always hustled, regardless of the score.”

Andy Pafko, a Cubs outfielder from 1943 to 1951, had the locker adjacent to Cavarretta’s. “I was honored to be dressing next to the great Phil Cavarretta,” he said. “I admired his hustle. He was a real competitor, and one of the most popular players in Chicago.”14

Cavarretta was especially popular with Italian American fans. In 1935, the local Knights of Columbus sponsored Phil Cavarretta Day at Wrigley Field. He recalled that they presented him with “a nice automobile and a 16-gauge shotgun, which I still have.” Even his parents became fans. “Once I went to the Cubs they took a little interest ’cause I was bringing in some money,” he said. “I’d get paid on the first and the 15th, and I’d bring the check to my mom and dad.”

Cavarretta remained in the game for many years after his playing days ended, working as a scout, coach, and minor-league manager. Married since 1936 to Chicago native Lorayne Clares, he had five children to support.15 For 11 years between 1956 and 1971, he managed seven minor-league teams in five different leagues, from the Florida Instructional League to the Triple-A International League. He coached for the Detroit Tigers from 1961 to 1963 before scouting for them, and from 1973 to 1977 he was the minor-league hitting instructor for the New York Mets. He completed his career by serving as the Mets’ hitting coach in 1978 under manager Joe Torre.

After retiring from baseball, Cavarretta and his wife lived for many years in Clearwater, Florida, before moving to Georgia, first to Villa Rica, then to Lilburn. He remained a loyal Cubs fan the rest of his life. On May 15, 1999, the 82-year-old Cubs legend returned to Wrigley Field to throw out the ceremonial first pitch. In an interview at that time he said, “Every day I wait for the Cubs games to come on cable TV. I watch all the games and I sit there and root for the Cubs.”16

Phil Jr., who pitched in the minors in 1977-78, confirmed that his father loved the Cubs and watched the games. “But,” he said, “he’d get aggravated when guys wouldn’t play the game the way it’s supposed to be played.” He added that in retirement his father “played a little golf, did a little fishing. But mostly he spent time with the family. He was a good father, always there for you, always understanding.”17

In 2001 Cavarretta, then living in Villa Rica, reflected on what baseball meant to him. “I don’t know what I would have done if it hadn’t been for baseball,” he said. “It was a game that I was proud to be a part of, proud of so many things that I learned from the game itself and the people that were affiliated with the game.”

After battling leukemia for several years, Cavarretta succumbed to complications from a stroke on December 18, 2010, in Lilburn, Georgia, at the age of 94. His remains were cremated. He was survived by his wife of 73 years; daughters Diana, Patti, Cheryl, and Lori; son Phil Jr.; and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Sources

Cava, Pete, ed., Tales From the Cubs Dugout (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, Inc., 2000).

Golenbock, Peter, Wrigleyville: A Magical History Tour of the Chicago Cubs (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996).

Hartig, Ed, “First Family: 1945 MVP Cavarretta Returns to Wrigley,” Vine Line, July 1999, 15.

Munzel, Edgar, “Run-’em-out Phil in 11-Year Cub Run,” Sporting News, May 31, 1945.

Chicago Cubs Yearbooks, 1941, ’42, ’51, ’53.

Chicago Tribune

New York Times

The Sporting News

Claire, Fred, “Time for Cubs to Finally Honor Cavarretta,” MLB.com, http://chicago.cubs.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20101224&content_id=16367164&vkey=news_mlb&c_id=mlb

Interviews: Phil Cavarretta, Phil Cavarretta, Jr., Len Merullo, Andy Pafko.

Thanks to Cubs historian Ed Hartig for his assistance.

Notes

1 Phil Cavarretta, telephone interview, April 29, 2001. Unless otherwise noted, all Cavarretta quotations are from this source.

2 Cava, Tales From the Cubs Dugout, 58.

3 Len Merullo, telephone interview, December 16, 2001.

4 The Sporting News, May 31, 1945. In his 20 years with the Cubs, Cavarretta played the outfield for parts of 13 seasons, in six of which he played the majority of his games in the outfield.

5 The Sporting News, July 25, 1940.

6 It was while he was managing that Cavarretta persuaded general manager Wid Matthews to close off a section of the center-field bleachers at Wrigley Field, arguing that the white shirts of fans in that area made it dangerous for hitters, who had a hard time seeing the pitch against the white background. See Golenbock, Wrigleyville, 320, and Hartig, “First Family,” 15.

7 The Sporting News, April 7, 1954.

8 Chicago Tribune, April 2, 1954.

9 In an email to the author (October 8, 2013), Cubs historian Ed Hartig, wrote, “I can only speculate that Cavarretta’s signing with the White Sox likely had something to do with (the lack of a formal retirement ceremony).”

10 Claire, “Time for Cubs to Finally Honor Cavarretta.”

11 In his October 8, 2013, email to the author, Hartig wrote: “I spoke with Hooton at the Cubs Convention several years ago. He recalled that Yosh Kawano called Cavarretta to ask permission to give the pitcher number 44. Cavarretta said it was OK.”

12 Phil Cavarretta, Jr., telephone interview, December 20, 2013.

13 The Sporting News, May 31, 1945.

14 Andy Pafko, personal interview, April 21, 2001.

15 Some sources list her name as Loraine, but in his telephone interview on December 20, 2013, Phil Cavarretta, Jr. confirmed Lorayne as the correct spelling.

16 Hartig, “First Family,” 15.

17 Phil Cavarretta, Jr., telephone interview, December 20, 2013.

Full Name

Philip Joseph Cavarretta

Born

July 19, 1916 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

December 18, 2010 at Lilburn, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.