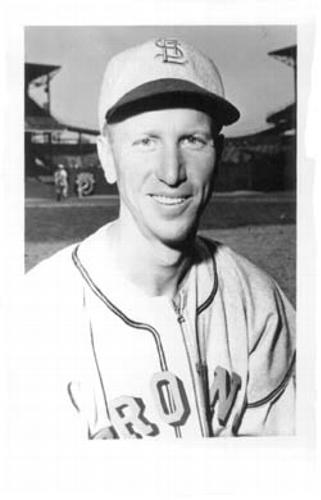

Chuck Stevens

He played 211 games in the major leagues, all of them for the St. Louis Browns, most of them on the short end of the score. Were that the only thing he had ever achieved in baseball Chuck Stevens would have plenty to be proud of, having climbed several rungs of the minor league ladder to achieve the dream of most every boy of his generation, to compete at Yankee Stadium and Sportsman’s Park, to play a game he loved at the highest level. But that was not all he accomplished in the game, not by a long shot.

He played 211 games in the major leagues, all of them for the St. Louis Browns, most of them on the short end of the score. Were that the only thing he had ever achieved in baseball Chuck Stevens would have plenty to be proud of, having climbed several rungs of the minor league ladder to achieve the dream of most every boy of his generation, to compete at Yankee Stadium and Sportsman’s Park, to play a game he loved at the highest level. But that was not all he accomplished in the game, not by a long shot.

He spent the better part of twenty years playing, coaching and managing professional baseball, much of it in the Pacific Coast League during the tail end of its heyday. When his career in a baseball uniform finally came to an end, he spent almost forty years lending a hand to former baseball people who had fallen on hard times. Stevens would tell you that he was lucky to be associated with baseball for so long, doing something he loved to do and gaining hundreds of lifelong friends. Stevens is only half right, however. Baseball has been very fortunate indeed.

Charles Augustus Stevens Jr. was born July 10, 1918, in Van Houten, New Mexico, up near the Colorado border. Charles Sr. was a cattleman his entire life, one who entertained his family by playing the fiddle and the guitar. Mother Ann was born in Scotland, and moved with her family to New Mexico as an infant. Charles and Ann raised four children, two a product of Ann’s first marriage (Cline, a boy, and Muriel, a girl), and two of their own (Mauverine, a girl, and Charles Jr.).

Within a few years the Stevens family moved to Long Beach, California, while maintaining the ranch in New Mexico. (In fact, it is still owned by the family in 2004.) The principal reason for relocating to Long Beach was to provide a better education for their children. The new arrangement provided the best of both worlds, as the family continued to spend their summers back in New Mexico throughout Chuck’s childhood.

The family was very interested in sports, and Long Beach’s strong recreation department, with its competitive baseball environment, made it a rewarding place to grow up. Chuck played baseball and basketball at a young age, but he also was always interested in music; he studied percussion for 12 years, and was also an accomplished tap dancer in his youth.

There was no “major league” baseball on the west coast in the 1920s and 1930s, but the Stevens family could still watch a high brand of ball by traveling to old Wrigley Field to see the Coast League’s Los Angeles Angels. The PCL ball players were Chuck’s heroes, the major leaguers being but a rumor in those days before television. Chuck’s maternal grandfather, raised in Scotland, was the big sports fan in the family, and often took Chuck on the trolley to see the Angels, fueling the youngster’s love for the sport.

Long Beach in the 1930s was a fertile breeding ground for major league players. Chuck’s teammates in high school or American Legion included people like Vern Stephens, Bob Lemon, and Bob Sturgeon, among many other future professionals. It wasn’t just Long Beach: some of Stevens’ opponents in these years included Ted Williams, Bobby Doerr and Jackie Robinson. Beginning the summer following his junior year in high school, he remained in Long Beach during the summer months on area diamonds playing first base, his life-long position.

Following his graduation from Long Beach Poly High School in early 1937, Stevens enrolled in school at the University of California at Berkeley, in the pre-dental program. He didn’t stay long, signing a professional baseball contract with Willis Butler, the west coast scout for the St. Louis Browns. Stevens was practical about his decision, giving himself four years to convince someone that he could make the major leagues.

He went to spring training in San Antonio, before reporting to Williamston (North Carolina) of the Class-D Coastal Plains League. He went through culture shock living in tobacco country, seeing the devastating effects of racial segregation up close. He was much more comfortable on the diamond, hitting .288 with 10 home runs in 97 games.

Although Chuck was naturally left-handed, he spent his youth hitting from the right side. In 1938, the Browns convinced him to try switch-hitting, and he stayed with it the rest of his career. In fact, it wasn’t long before he felt more comfortable hitting left-handed, likely because a hitter always sees many more right-handed pitchers. He started this experiment with Johnstown (Pennsylvania) of the Class-C Middle Atlantic League, where he hit .290 in 128 games. The difficult thing Stevens remembers about that summer was the losing-the Johnnies finished in last place in the eight-club circuit.

For 1939 the Browns promoted Stevens to Springfield (Illinois) of the Class-B Three-I league, and he enjoyed his best minor league season (.316 with 74 runs batted in) for a team that won the Three-I championship. Now 21 years old, Stevens’ rapid advancement through the system indicated that he was considered a major league prospect. Stevens moved up again in 1940, this time to San Antonio of the Class-A Texas League. He didn’t hit quite as well (.264 in 158 games), but was drawing attention for his flashy defense and aggressive base running. He was added to the Browns roster in September, but did not get into any games.

The best move Stevens made in his life took place in January 1941, when he married Maria, a friend of his sister whom Chuck had known since grammar school. Like many of his childhood friends-Vern Stephens and Bob Lemon among them-he married a local woman and remained in the Long Beach community. They raised one child, a daughter named Randall.

For the 1941 season Chuck joined Toledo of the Double-A American Association, one step below the major leagues. He had a fine year for the Mud Hens (.290 in 145 games), playing for Fred Haney. Fred and his wife Florence took a liking to Chuck and Maria, and the Stevens felt they had discovered a second set of parents. In particular, Chuck was very fond of his new manager, and they remained friends for the rest of Haney’s life. At the close of the season, Stevens joined the Browns again, and got into four games, collecting 2 hits in 13 at bats before a pulled groin muscle shut him down for the season.

In December 1941 Stevens was having breakfast with his wife when he got word of the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor. This was a life-changing moment for all Americans, but especially for the people on the West Coast who had to deal with rumors of another attack closer to home. As a married man Stevens was not subject to military induction immediately, but he knew that his day would soon come.

Stevens returned to Toledo in 1942 but had a disappointing season. Considered the heir apparent to George McQuinn, the Browns’ incumbent first sacker, Stevens slumped to .250 and did not get the September recall he was likely hoping for. After the season, Stevens’ draft board let him know that his call-up was imminent, and he subsequently entered the Army Air Force.

He spent the next three years in the AAF, first in California and later in the Pacific theatre, in Tinian, Guam, and Okinawa. Stevens’ specialty was crash-and-burn recovery, saving men and supplies in downed aircraft. Amidst all the horror, Stevens also played baseball, in Long Beach during training and later in Hawaii.

Like most of his baseball peers, the ending of hostilities in 1945 brought Stevens home to resume his life and baseball career in 1946. George McQuinn, who played through the war and had held the Browns’ first base job for eight years, was traded during the off-season for the Athletics’ first baseman, Dick Siebert. However, Siebert refused the Browns’ proffered salary cut, providing Stevens a job opening. The Browns tried to get the trade rescinded, but the American League upheld the deal. Siebert never played in the major leagues again.

Stevens played 122 games for the 1946 Browns and hit .248 with three home runs. He never had much power, topping out at 12 home runs in the minor leagues, and this undoubtedly kept him from a longer career in the majors. His defense and base-running were generally first rate.

In 1947 Stevens was outrighted back to Toledo, switching jobs with Jerry Witte, who had hit 46 home runs for the Mud Hens in 1946. The Browns soon regretted the move and tried to recall Stevens in June but were told that he would have to pass through waivers to come back up during the season. Accordingly, Stevens spent the entire campaign in Toledo, where he batted .279 in 141 games.

The Browns gave Stevens his old job back in 1948, just in time to take part in a bit of baseball history on July 9 in Cleveland. Chuck’s old friend Bob Lemon started for the Tribe, but when he fell behind 4-1 he was relieved by Satchel Paige to start the fifth inning. It was Paige’s first game in the “major leagues,” and the first batter he faced was Chuck Stevens. Chuck had faced Paige many times in exhibition matches in California, and remembered hitting him pretty well. In this instance, he spoiled the story by lining a single to left field on the second pitch he saw. Paige retired the next three hitters to get out of the inning unscathed.

The Browns’ devotion to Stevens lasted only 85 games this time around, during which Chuck hit .260. They tried to farm him out to San Antonio on July 26, but by this time Stevens had had enough and refused to go. He packed up his wife and daughter Randall and headed back to Long Beach. Stevens requested that he be sold to the Hollywood Stars, and the Browns relented a few weeks later. Stevens hit .321 over 38 games for Hollywood at the tail end of the 1948 season.

The Hollywood years, which lasted into 1954, were the favorite ones of Stevens’ baseball career, back home with his friends and family. In 1949, Fred Haney became the manager of the Stars, reuniting Stevens with his favorite skipper. Even better, the Stars won three PCL championships while Chuck was their first baseman (1949, 1952, and 1953), and had strong teams in the other seasons as well. Like most players, he much preferred going to the ballpark when he felt the team was going to win.

Stevens also parlayed his local fame into roles in two baseball related movies, appearing in Sam Wood’s The Stratton Story, which starred Jimmy Stewart and June Allyson, and Lewis Seiler’s The Winning Team, featuring Doris Day and Ronald Reagan. Stevens played Earle Combs in the latter film.

The Hollywood Stars created a stir in 1950 when they outfitted their squad in shorts and T-shirts. Stevens was the first man to bat in the new uniforms, leading off the first inning of an April contest with an infield single. Fred Haney, coaching at first base, yelled to the crowd, “He wouldn’t have made it with the old unis!” Although the players took a lot of ribbing, many baseball people, including Branch Rickey, felt that it was only a matter of time before shorts became the norm in the major leagues.

Stevens was remarkably consistent during his Hollywood years, hitting .297, .288, .292 and .278 from 1949-1952, playing his typical solid defense at first base. He did not have a lot of power (topping out at 12 home runs in 1950) but was often employed as the team’s leadoff hitter. His best stretch of hitting occurred in the first half of 1950, highlighted by 10 straight hits in May. A Detroit scout visited Hollywood to look at possibly acquiring Chuck’s contract, but a foot injury caused a slump for much of the second half of the season.

Chuck’s teammates looked to him for more than just slick fielding and an occasional big hit. The Sporting News reported in 1950 that Stevens was “bellcow, mother hen and watchdog all rolled into one.” Calling him the team’s “unofficial assistant manager,” he was described as the player who held the team together on the field: encouraging, prodding, exhorting.

Stevens began to slow down at the plate in 1953 (.230 in108 games) and lost playing time to Dale Long (who played the outfield when Stevens was in the lineup). The next year Long won the position outright, and the Stars sold Stevens contract to the San Francisco Seals. Chuck played for the Seals for the next year and a half as a reserve player and pinch hitter, also serving as a player-coach for the 1955 campaign. In the latter job, he worked for Tommy Heath, a man Stevens had tremendous respect for as a manager.

At the end of the 1955 season, the Boston Red Sox, who purchased the Seals after the 1955 season, sent Chuck along with some of their other surplus players to Louisville of the American Association, their former farm club. Stevens had no interest in going to Kentucky, instead buying out his own contract so that he could take an opportunity to manage the Amarillo Gold Sox in the Western League.

He hit well in Texas (.335), and also managed his team to the league’s title series, copping the circuit’s manager of the year award. Stevens had been considered managerial timber by the Browns several years earlier, and many people assumed that he would eventually end up managing in the major leagues. Instead, he walked away from the job after just one season, deciding that it was too much stress and too much time away from his wife and daughter.

His career was not quite finished. Tommy Heath was now managing at Sacramento, and he convinced Stevens to join him as a player-coach in 1957. He played sparingly, gathering just three singles in twenty-one at bats. Heath moved to Portland in 1958 and tried to convince Stevens to come with him, but Chuck decided that the end had come. He finally hung up his uniform at age 39.

Rejoining his Long Beach community full-time, Stevens first took a job working in private industry, for a company that acidized oil wells. He soon ended up as the general manager, but only long enough to help broker the sale of the company.

In early 1960 Pants Rowland contacted Stevens about a vacant job as secretary of the Association of Professional Ball Players of America (APBPA). Founded in 1924, APBPA is an association of former baseball people that supports those of its members in need. The organization is not limited to major leaguers or to players, assisting umpires, scouts and trainers as well. Stevens interviewed for the post with J. G. Taylor Spink of The Sporting News, a long time supporter of the Association. Stevens soon became its fourth secretary, following Russ Hall, Win Clark, and Bobby Adams. He kept the job for 38 years, until he had reached the age of eighty.

Stevens was immediately instrumental in modernizing the structure of organization, setting up a constitution and By Laws to conform to new tax laws. The heart of the job was not organizational, however. It was hearing from people every day who needed help, and working out a way to provide that help.

His job kept him in touch with the baseball community. The group gets its operating funds from the dues of its members, with donations also coming from the commissioner’s office and major league teams. Stevens was responsible for keeping players aware of the organization, either via face-to-face meetings or mail solicitations. If a baseball person was in need, someone would get hold of APBPA, and Stevens was responsible for verifying the claim and working out a way to help. In Stevens’ words, he wanted all of these people to “live with dignity.”

In 1982, the Association got a measure of fame by staging the Cracker Jack All-Star game at RFK Stadium in Washington, D. C. It was an old-timers game, but one in which the players played seriously and to win. Unlike other vaguely similar events, it was not held prior to a major league game-it was a standalone event. Chuck was responsible for getting the players, and he rounded up almost all of the living members of the Hall of Fame. He also managed the American League team, and made sure (as did the NL team) that people played the positions they played during their careers.

The first event, held July 19, 1982, became famous when Luke Appling hit a home run off Warren Spahn. There were a total of eight games, held either at RFK Stadium or at Memorial Stadium in Buffalo. The event eventually faded away, in large part because the market for such games had been saturated by other, lesser, affairs. There was a touring version that played before major league games for several years, with players playing out-of-position, hitting wrong-handed, and the like, helping create the impression that all such events were mere silliness. Stevens is justly proud to make the distinction.

Stevens was the secretary of APBPA from 1960 until 1998. It was a job that required a lot of work, involved long hours at the office, and “broke your heart every day.” The files of the association are filled with letters thanking Stevens personally for his kindness and thoughtfulness. “I want the association to know that my gratitude, appreciation, and gratefulness accompany my letter to you now.” “I will never be able to thank you for your help and kindness.” “I am thankful for the assistance provided for me and my invalid wife in our hour of need.”

In the 21st century, Stevens lived with his wife of more than six decades, “Mrs. Stevens,” in a town not far from where they both grew up. He spent his entire life involved in baseball, playing, coaching, managing, helping, and being an enthusiastic part of the baseball community. He still loved the game, loved talking about all of his great memories, and enjoyed creating new ones. He received a lot of pleasure from the this old game, but one can’t help thinking he put more than his share back into it.

At the time of his death on May 28, 2018, at the age of 99, Stevens held the distinction of being the oldest living former major-league player.

Sources

A primary source of this article was a series of delightful conversations I had with the subject in December 2003 and January 2004. I also had the kind assistance of Dick Beverage, who has known Stevens for many years and who succeeded him as Secretary of APBPA. I also made use of a number of articles in the Sporting News, viewed via the Paper of Record service at www.paperofrecord.com, and the Stevens file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Other sources:

Beverage, Richard E. The Hollywood Stars. Deacon Press, 1984.

Dobbins, Dick. The Grand Minor League. Woodford Press, 1999.

Johnson, Lloyd and Miles Wolff. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 2nd Edition. Baseball America, 1997.

Kelley, Brent P. The San Francisco Seals, 1946-1957. McFarland, 2002.

Full Name

Charles Augustus Stevens

Born

July 10, 1918 at Van Houten, NM (USA)

Died

May 28, 2018 at Long Beach, CA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.