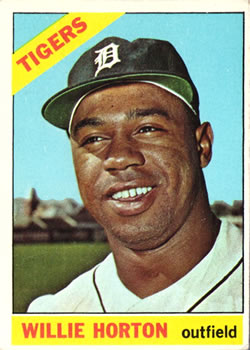

Willie Horton

A standout on the sandlots of Detroit, Willie Horton became the first black superstar for his hometown Tigers and spent parts of 15 seasons with the team. A tremendously powerful right-handed slugger, Horton was one of the strongest men in the game and launched 325 homers in his career. Extremely popular in Detroit, Horton worked in the Tigers front office after his playing career, where he helped bridge relations between the club and the African American community.

A standout on the sandlots of Detroit, Willie Horton became the first black superstar for his hometown Tigers and spent parts of 15 seasons with the team. A tremendously powerful right-handed slugger, Horton was one of the strongest men in the game and launched 325 homers in his career. Extremely popular in Detroit, Horton worked in the Tigers front office after his playing career, where he helped bridge relations between the club and the African American community.

Born in Arno, Virginia, on October 18, 1942, William Wattison Horton was the youngest of 14 children—eight of them boys—of Clinton and Lillian Horton. His father moved the family to Detroit when Willie was five years old. Raised in the shadows of Briggs Stadium in the Jefferson Projects in downtown Detroit, Horton was a talented athlete despite his short, stocky frame that carried extra baby fat. Horton was a left-handed batter until age 10, when his father changed him to right-handed in Little League.

As a 17-year-old in 1960, he played outfield for the Detroit Lundquist team that won the national sandlot championship in a tournament in Altoona, Pennsylvania. Horton batted third on that team, directly in front of Bill Freehan, who would later be a teammate of Willie’s on the Tigers. As a star slugger at Northwestern High School in Detroit, Horton hit a home run at Tiger Stadium in the city championship game, and earned the nickname “Willie the Wonder.” After his senior year, the Tigers signed Horton to a $50,000 bonus.

At Duluth-Superior in the Northern league in 1962, Horton enjoyed a fine rookie season in pro ball, batting .295 with 15 home runs and earning comparisons to a young Roy Campanella because of his physical appearance and power from the right side of the plate. The performance earned him a promotion to Triple A Syracuse in 1963, but he was overmatched and quickly sent down to Knoxville of the Sally League, where he flourished with a .333 mark and 14 home runs. At Knoxville he earned a reputation for hitting the ball well to all fields. Called up by the Tigers at the tail end of the ’63 season, Horton came through in his first two pinch-hit at-bats and finished the season with a 6-for-10 stretch against the Orioles.

Willie made a name for himself during spring training in 1964 when he led the team in home runs and drove in 18 runners. On Easter Sunday, he clubbed a ninth-inning, pinch-hit homer more than 420 feet to deep center field to win the first game of a doubleheader, and hit another game-winning homer in the second game. His play—and his weight—caught the attention of manager Charlie Dressen. The Tigers skipper stripped more than 20 pounds from Horton’s frame during the spring, after the youngster reported weighing 222 pounds.

“He looks like a natural hitter to me,” Dressen said. “Willie throws good, and he can run.”

His spring heroics earned Willie a spot on the Tigers’ roster, and he began the season platooning with veteran Bill Bruton in left field. But Horton struggled, especially against off-speed pitches, and slumped to an 8-for-59 start (.136 with no home runs). In mid-May, the Tigers shipped Horton to Triple A Syracuse, where Willie felt more comfortable playing every day, slugging 28 homers and batting .288 with 99 RBI for the Chiefs. His efforts earned him another late-season call-up to Detroit. In his final game of the season, Horton clubbed a home run against Milt Pappas in Baltimore.

While playing winter ball in Puerto Rico in early 1965, Horton received tragic news. Both of his parents were killed in a New Year’s Day car accident in Albion, Michigan. Horton quickly flew home to attend the services. The youngest child, Horton had been particularly close to his father, who had been in the stands at Tiger Stadium when his son hit his first major league home run, victimizing Robin Roberts.

Overcoming the death of his parents, Horton lost his usual off-season weight during the spring and made the big league club. “Whatever I do this year, I’m doing for my dad and mother,” Willie said. He began the 1965 season as Detroit’s fourth outfielder. But his hot-hitting quickly won him the left field job from Jim Northrup and earned him a spot on the American League All-Star team. In 143 games, the 22-year-old batted .273 with 29 homers and 104 RBI, finishing eighth in Most Valuable Player Award voting. During an East Coast road trip to Washington and Boston in May, Horton socked six homers in four games, each of the blasts traveling more than 400 feet. “Willie the Wonder” had arrived on the big-league scene.

Having established that he could hit right-handed pitching well enough to be in the lineup on a daily basis, Horton was entrenched in the starting lineup for Detroit in 1966. Once again he put up big offensive numbers, driving in 100 runs on the strength of 27 home runs. An ankle problem hampered him in 1967, but Willie still managed 19 homers and 67 RBI in 122 games. With the Tigers battling into the final weekend in a four-team race for the pennant, Horton hit homers in the first inning of the first games of doubleheaders on the last two days of the season to help defeat the Angels. However, Detroit lost the flag by one game.

That season, Horton thrust himself into the Detroit riots, fleeing Tiger Stadium in uniform to address the irate crowds in the streets of fire. Showing tremendous courage, Horton pled with Detroiters to calm the violence, but his efforts were in vain, and the city burned for nearly a week.

Horton was the most consistent bat in the Tigers’ lineup in the magical 1968 season. In a season dominated by brilliant pitching performances, Horton’s .285 average was fourth in the league, and his 36 homers were second to Frank Howard’s 44. In the World Series against the Cardinals however, it was Willie’s right arm that won him eternal fame with Detroit rooters. In the fifth inning of Game 5, with Detroit trailing 3–2 and St. Louis threatening to extend its lead, Lou Brock tried to score standing up on Julian Javier’s single to left field. Horton fielded the ball and fired a one-hopper to home plate. Freehan caught the ball and tagged Brock to swing the momentum in Detroit’s favor. The Tigers came back to win the game, 5–3, and captured the final two games to win the title. Horton batted .304 with six runs scored and three extra-base hits in the Series victory.

In contrast with the previous season, 1969 was filled with disappointment for Horton. Mired in a 4-for-35 slump on May 15, Willie left the team midgame and disappeared for four days due to “personal pressures.” When he came back, he had lost more than $1,300 in pay and was admonished by Detroit General Manager Jim Campbell. On June 28 in Baltimore, Horton pulled up at second base on a double and tore thigh muscle in his right leg. The injury forced him to miss 10 games and relegated him to the bench for seven more. He played the final weeks of the season with a sore right hand. Nonetheless, Horton still managed 91 RBI and 28 home runs.

Horton tried something different during the off-season, doing road work in Detroit in the ice and snow to keep his weight down. He arrived for spring training in Lakeland in 1970 in the best shape of his career. But an injured ankle ended one of his best seasons on July 24 with his batting average at .305 with 17 home runs and 69 RBI. He enjoyed a career-high 15-game hitting streak and had one of the best days of his career on June 9, when he slugged three homers‚ including a grand slam‚ and knocked in seven runs in Tiger Stadium against Milwaukee.

More adversity came Horton’s way in 1971, when on August 27, he was struck in the left eye with a pitch from Rich Hinton of the Chicago White Sox. The injury kept him out of the lineup for a month, but Willie still managed 22 homers, 72 RBI, and a .289 average in 119 games. On team picture day, sulking over a perceived slight by the front office, Willie refused to pose for the team photo. In the final game of the season at Cleveland, Horton butted heads with manager Billy Martin. After grounding out, Horton failed to run down the baseline, and Martin pulled Willie from the game, embarrassing the slugger. “I’m through playing in Detroit,” the sensitive Horton snapped. But, Martin and Horton, who later became very good friends, mended their differences.

Detroit returned to the postseason in 1972 while Willie suffered one of his most frustrating seasons, hitting .231 with 11 homers in 108 games. He reported to spring training overweight and fought hard to shed the pounds, but never got on track, and suffered foot and shoulder ailments that hampered his effectiveness.

Following that disappointment, Horton arrived at spring training in 1973 in good shape and focused on a return to form. He did just that, hitting .316 in 111 games, spending much of the season among the batting leaders in the league. Now 30 years old, Horton continued to have troubles with his legs, especially after the All-Star break, which limited his playing time. “By the fourth inning my legs are so stiff the way it is that I can hardly move,” Willie said. Horton also injured his wrist when he ran into a wall chasing a fly ball, but he credited his new roommate, veteran slugger Frank Howard, with helping him have one of his better seasons. He was also helped by a new daily exercise regimen that involved a broom handle Willie called “the wand.”

Yet despite the broom handle, his nagging legs bothered Horton again in 1974, and in early July, after nearly a month without hitting a homer, he was shut down and underwent knee surgery. Even though he had been unable to run very well all season, Horton had managed to hit .298 with 47 RBI in 72 games. In April he was involved in a bizarre incident at Fenway Park when he lofted a high foul fly directly over home plate that struck a pigeon. The bird landed at the feet of Red Sox catcher Bob Montgomery. On the next pitch, Willie singled.

With the retirement of Al Kaline following the 1974 campaign, Horton was now an elder on the club. Having always been sensitive to his status in the clubhouse, Horton aimed to have a big 1975 and boost his salary into the $100,000 mark that Kaline had received. Spurred by that possibility, Horton stayed healthy all season for the first time in six years. Manager Ralph Houk helped the situation by using Horton exclusively as a designated hitter. Horton played in 159 games and set career marks at that time for hits and at-bats. His 92 RBI were 32 more than any other Tiger, and his 25 homers were nearly double that of any of his teammates. He was named DH on The Sporting News’ AL All-Star team. Though he was not sure at first if he would like being a DH, Horton warmed to the role as the season wore on.

“The only reason I thought I might not like it was because I thought it might feel like I wasn’t doing enough for the club,” Horton said. “It’s not that way though. Now I have to keep up with what’s going on all the time.”

But in November, Willie expressed his desire to put a glove on again, either in left field, or at first base. “I just turned 32 [he was really 33] and I don’t want to think I can’t do nothing but sit around and hit the rest of my life,” Horton said.

With a fresh new $105,000 contract when the 1976 season opened, Horton was in the DH spot again as a veteran bat on a team rapidly getting younger with outfielders Ron LeFlore, Danny Meyer, and Ben Oglivie, first baseman Jason Thompson, and pitching phenom Mark Fidrych. “These kids are just coming along, just getting started, and I want to help them,” Horton said. “I want them to learn to live on and off the field. I want them to learn to live together.”

Horton got off to a strong start, leading the league in homers in April and earning Player of the Month honors. But Houk sat Willie against certain pitchers, shuttling Rusty Staub into the DH spot once or twice a week. Sulking, at one point Horton refused to take batting practice or shag flies. Then, in early June he hurt his knee and missed more than a month. When he returned, he was less than 100 percent and his average dropped from .299 to a season-ending mark of .262 with spotty power. With Staub, a defensive liability in the outfield, having an All-Star season, it was apparent Horton’s DH slot was in jeopardy. Willie still begged to play left field again, but the emergence of Steve Kemp made that unlikely. Years of injuries had caught up with Willie, who at 33 was breaking down more often every season.

“If I had been the type of guy who could go out there and not play hard, I probably would have never gotten hurt,” Horton lamented. “But when you play hard, you’re going to get hurt—I don’t care who you are. I’m the type of guy who, if there’s a fly ball hit to me, and I’ve got a chance to catch it, I’m going to try to catch it—even if we’re 12 runs behind. That’s one of the reasons I get hurt so much, running into walls and falling and stuff like that.”

Horton’s tenure with his hometown team came to an end early in the 1977 season. After going 1-for-4 in left field on opening day against the Kansas City Royals, he sat on the bench until he was traded to the Rangers five days later. With a backlog of outfielders and Staub at DH, the Tigers shipped their disgruntled slugger to Texas for reliever Steve Foucault. Willie packed his bats and his helmet (he wore the same helmet throughout his career, having it painted when he changed teams) and joined his new club. It began an odyssey for Horton that took him to six different teams in three seasons.

Horton never was accepted in Texas, where the team owner, Brad Corbett, had made the deal for him without consulting his baseball people, least of all manager Frank Lucchesi. The Rangers had several DH candidates on their roster and their own outfield logjam. Yet with his thundering bat, Willie found playing time, appearing in 139 games, blasting 15 homers, and finishing second on the club with 75 RBI. But in the off-season, he was dealt to Cleveland with former pitching phenom David Clyde for reliever Tom Buskey and outfielder John Lowenstein. The Indians were the first of three teams that Horton played for in 1978, finding himself released in July, signed by Oakland, and then swapped to the Toronto Blue Jays a month later with Phil Huffman for Rico Carty. Through it all, Willie still proved to be a run producer—driving in 60 runs in 115 games.

In the off-season, Horton tested the free agent market for the first time and received his long-sought-after two-year deal—with the Mariners. In Seattle, as a veteran on an expansion club, Willie found a comfortable environment and enjoyed playing for manager Darrell Johnson, who inserted Horton’s name in the lineup every day. Willie rewarded Johnson’s confidence, slugging 29 homers with 106 RBI, a career best, and earning American League Comeback Player of the Year honors. Seattle fans fell in love with 36-year-old Horton, dubbing him the “Ancient Mariner.”

Facing his former Tigers team June 5, 1979, Horton belted a ball at the Kingdome in Seattle that disappeared in the roof in left-center field. Initially ruled a home run—the 300th of his career—it was changed to a single when it was determined that it had struck a speaker. The next game, Horton hit his for-real 300th homer off Detroit’s Jack Morris.

With a two-year extension in his pocket, Horton got off to a dreadful start in 1980, and without a home run to his credit and his average languishing below .200, he sat for two three-game stretches during May. Later he spent two stints on the disabled list with a hand injury. He finished his 18th season with a .221 average and just eight home runs. He entered the off-season knowing he would have to fight for a job on the Mariners, but that didn’t matter on December 12, when he was dealt to the Rangers as part of an 11-player trade. After spring training in 1981, Horton was released by Texas. His career seemed over, but a month later the Pittsburgh Pirates signed him to a minor league deal and assigned him to Portland in the Pacific Coast League. Willie showed flashes of his power for the Beavers, stringing together a 10-game hitting streak at one point. Just seven hits away from 2,000 for his career, Willie was determined to get back to the major leagues, but it never materialized. He spent one more season in the minors and played briefly in the Mexican League in 1983, but returned home frustrated.

“I know I can still help a club,” Horton said. “Even if I never touch a bat again, I know one thing: I can still help somebody.”

Horton finally found that opportunity with an old ally—Billy Martin. The Yankees skipper brought Horton to New York in 1985 as his “harmony coach.” Essentially, Willie was responsible for making sure that Martin’s players didn’t divide into warring factions in the clubhouse. Much of Horton’s time was spent spying on the players and reporting to Martin. He served in a similar capacity for the Chicago White Sox in 1986. In 2000, he was brought back into the Tigers organization by owner Mike Ilitch as a special adviser, and he still serves the team’s front office today. A bronze statue of Horton taking a mighty swing is located at Comerica Park beyond the left-field stands, and Willie is the only non-Hall of Famer to receive that recognition. His uniform number 23 was also retired by the club.

In 2004, Horton was dealt a setback when he was hit by a car, and in 2006 he was diagnosed with prostate cancer. Horton and his wife, Gloria, with whom he shares seven children and 19 grandchildren, reside in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. Throughout his post-playing years, Horton busied himself with charity work for many organizations, including the Foundation for Fighting Blindness, the Boys and Girls Club of America, Meals on Wheels, the Red Cross, and the United Way. He also established the Horton Foundation to provide scholarships for needy students in inner-city Detroit. In 2004, Michigan Governor Jennifer Granholm declared Willie’s birthday, October 18, as “Willie Horton Day” in Michigan.

“Willie Horton is one of those rare baseball players who doesn’t need a diamond to truly sparkle and shine—he’s a star on and off the field,” Granholm said. “This fitting recognition will continue to inform future generations of his accomplishments.”

On September 27, 1999, the final game was played at Tiger Stadium in Detroit. As part of the postgame festivities, former Tigers ran onto the field in uniform and took their positions. When Horton ran into left field, he was greeted with a tremendous ovation from fans who appreciated his 15 seasons and 262 home runs wearing the Detroit uniform. Willie Horton, the slugger who starred for the 1968 World Champions, the little kid from the streets of Detroit, the teenager who belted a homer nearly out of the ballpark, the strong man who shattered bats with brute strength, broke down and cried like a baby.

Sources

Detroit Tigers Yearbooks, 1963–1976.

Eldridge, Grant, and Karen Elizabeth Bush. Willie Horton: Detroit’s Own Willie the Wonder. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. 2001.

Ewald, Dan. John Fetzer: On a Handshake—The Times and Triumphs of a Tiger Owner. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. 2000.

Harrigan, Patrick. The Detroit Tigers: Club and Community, 1945–1995. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 1997.

The Sporting News: April 4, 1964, p. 23; April 11, 1964, p. 8; July 4, 1964, p. 31; January 1, 1965, p. 10; March 20, 1965, p. 8; May 29, 1965, p. 13; June 19, 1965, p. 18; July 24, 1965, pp. 3–4; January 22, 1966, p. 6; January 22, 1966, p. 12; February 26, 1966, p. 29; August 6, 1966, p. 13; March 25, 1967, p. 11; October 28, 1967, p. 19; December 23, 1967, p. 29; June 1, 1968, p. 7; July 20, 1968, p. 3; September 28, 1968, p. 7; February 1, 1969, p. 29; August 16, 1969, p. 15; February 21, 1970, p. 34; June 6, 1970, p. 19; July 4, 1970, p. 9; May 8, 1971, p. 19; January 15, 1972, p. 51; February 10, 1973, p. 41; April 14, 1973, p. 26; May 5, 1973, p. 11; September 8, 1973, p. 13; March 30, 1974, p. 30; June 15, 1974, p. 7; February 22, 1975, p. 42; June 28, 1975, p. 21; November 1, 1975, p. 15; May 22, 1976, p. 3; March 26, 1977, p. 8; April 30, 1977, p. 6; April 30, 1977, p. 16; May 28, 1977, p. 29; June 3, 1978, p. 29; August 19, 1978, p. 13; December 9, 1978, p. 42; May 26, 1979, p. 11; January 19, 1980, p. 35; May 17, 1980, p. 11; November 8, 1980, p. 49; January 17, 1981, p. 38; June 13, 1981, p. 48; November 7, 1981, p. 61; August 1, 1983, p. 24.

Willie Horton player file; National Baseball Library (various clippings)

www.retrosheet.org

Note

This article originally appeared in the book Sock It To ‘Em Tigers–The Incredible Story of the 1968 Detroit Tigers, published by Maple Street Press in 2008.

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

William Wattison Horton

Born

October 18, 1942 at Arno, VA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.