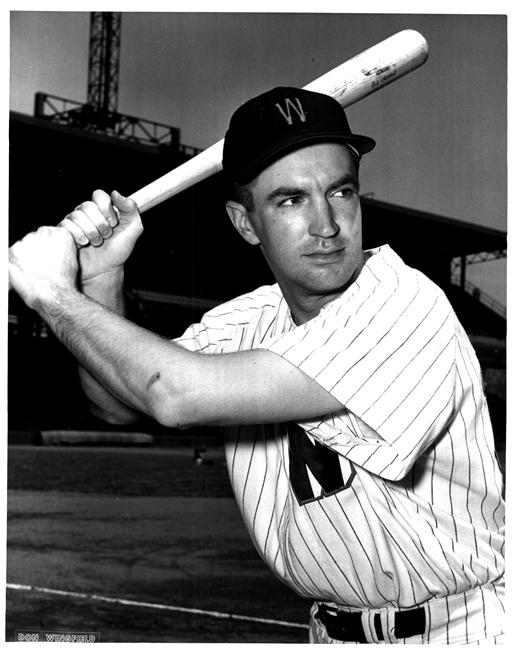

Dick Tettelbach

Opening Day, 1957. Dick Tettelbach, slated to play left field and bat second for the home-standing Washington Senators against the defending world champion New York Yankees, is nervous.

Opening Day, 1957. Dick Tettelbach, slated to play left field and bat second for the home-standing Washington Senators against the defending world champion New York Yankees, is nervous.

That was how, in 1990, the Yale-educated Tettelbach, who died in 1995, remembered “my first big game in the majors.” With former Yale baseball teammate George Bush in the White House, New Haven-born (June 26, 1929) Tettelbach was very much in demand by the media.

“Ed Rommel was the home plate umpire,” he said. “Before the game started he came up in the dugout. With all the ballyhoo and fanfare, President Eisenhower and Vice President Richard Nixon being there and all, I guess I was standing around with my mouth open, a little awestruck. Rommel looked at me and asked, ‘What’s the matter, kid?’ I said I was a little taken by the whole thing. ‘Don’t worry,’ he replied. ‘All the good kids have butterflies when they first start out.’ ”

Tettelbach had spent five years in the Yankees farm system, and had made his major-league debut as a Yankee the previous September. He had been traded to the Senators in the offseason.

It was Nixon who “got me into it,” Tettelbach said. “It was kind of an overcast day. Nixon was leading the group out to the flagpole. He had a coat he didn’t want to wear because the sun poked through, so I held it for him. That got me into it.”

The Yankees had a 1-0 lead, the result of a mammoth home run by Mickey Mantle, when Tettelbach came up in the bottom of the first. “God, I had never seen anything like that, a rocket, dead center field, 500 feet high, 550 feet long, over a tree that stood behind the wall 440 feet from home plate and 50 feet high.”

The Yankees’ pitcher was Don Larsen, a teammate the previous summer in Denver (American Association).

“Larsen knows I look for the curve, that I hit the breaking ball pretty well,” Tettelbach said. “Fastball, ball one. Fastball, ball two. 0 and 2 pitch, in all honesty I think it was a strike, high in the zone, but Rommel said ball three. Yogi muttered something. I took a deep breath. I think Rommel did me a favor. Then Larsen threw a fastball for a strike and it’s 3 and 1. I had a good cut at another straight ball, fouled it off. Then the 3-and-2 pitch, the sixth straight fastball, home run. When you see six in a row at the same speed you ought to be able to get a piece of it and I got it over the left-field wall. It was a fly ball, 10 or 15 feet inside the pole. I really, truly thought Ellie Howard had a play on it.”

Tettelbach’s feat, according to the Associated Press, marked the first time a Senator broke in with a home run. There were six homers in the game, including another mammoth shot by Mantle and two by the Senators’ Karl Olson. Only Mantle’s two would have cleared the 1955 Griffith Stadium fences; the Senators had brought them in for ’56.

It was Tettelbach’s greatest day on the diamond. For him it had been an epic struggle. Stricken with rheumatic fever as a youngster and left with a heart murmur, he played only one season in high school (Hillhouse, in New Haven) and had to beg for a second chance to make the Yale freshman team.

Signed by the Yankees in 1951, Tettelbach worked his way through New York’s farm system. On September 12, 1955, after hitting .309 with 16 home runs for the Ralph Houk-managed Denver Bears, Tettelbach got the call from the Yankees. He had spent five years in the minors, hitting better than .300 four times and being named an All-Star three times.

He made his major-league debut in a doubleheader the last day of the season, September 25, in Boston. He started the first game against the Red Sox, grounding out to short against Frank Sullivan. The next time up, there were two on and manager Casey Stengel called him back in favor of Mantle. Mickey had 99 runs batted in, and Stengel said he owed Mantle the opportunity to reach 100. Stengel did, however, let Tettelbach play the entire second game. He was 0-for-4, reaching base once on an error. (Mantle failed to get RBI No. 100.)

Tettelbach faced daunting competition in his effort to stick with the Yankees. “I was in a tough situation,” he said. “The Yankees were loaded with outfielders and they could all hit with power.” In his five years in the chain, the Yankees won the pennant four times with outfield mainstays Mantle, Hank Bauer, Gene Woodling, Irv Noren, and Bob Cerv.

He said he was delighted when the Yankees, in the offseason, sent him to the Senators, along with catcher Lou Berberet, infielder Herbie Plews, pitcher Bob Wiesler, and a player to be named later (Whitey Herzog) for pitchers Bobby Kline and Mickey McDermott. “No way was I going to play in New York,” he said. “They were just loaded. If I stayed with the Yankees I’d have gone to spring training but would have wound up back in the minors.”

The Associated Press was less sanguine: “He was regarded as a fine prospect but not quite ready for 1956.” Casey Stengel’s comment was less germane but classic: “And we lose Tettelbach who was a Yale man and that, of course, will cost us socially.”

For whatever success he had up to that point, Tettelbach was quick to credit Yale baseball coach Ethan Allen, saying of the former major-league outfielder that he “was just like Stengel, so thorough on fundamentals. When I got to pro ball after being exposed to Ethan for three or four years, I really knew more baseball than most of the guys in the major leagues. He knew it inside and out. I loved it and I knew I had to play that way or I wouldn’t have been anywhere because the raw ability wasn’t there. Ethan Allen was A-plus, totally the best coach I ever played for.”

Going out for baseball as a Yale freshman, he “got two swings in batting practice and wound up being cut” by freshman coach Phil Monvees. He spoke up, got another shot and made the team.

A bigger challenge came in 1948 when the 18-year-old Tettelbach looked for a spot on a team that had gone to the 1947 College World Series, and included war veterans like first baseman George Bush, catcher Norm Felske, and infielder Red Matthews, and other standouts like pitcher Frank Quinn and infielder Artie Moher. “In some [instances] there were five or six years difference in age,” Tettelbach recalled. “I was the little kid on the team. Those guys took me under their wing.”

He won the starting job in center field and batted second behind Moher, the spot in the order he filled for much of his pro career. Tettelbach was much in demand after Bush was elected president in 1988. He recalled a paid trip to Los Angeles along with his college roommate Paul Russ to appear on a “What’s My Line”-type program called “The Third Degree.” The panel figured it out quickly.

It was compensation, perhaps, for not being part of Yale’s return to the College World Series, in Kalamazoo, Michigan, in ’48. After one of his best days, a 4-for-6, 5-RBI performance against Brown in mid-May, he cracked a bone in his leg fooling around on the Yale golf course. “I jumped off the 10th green into a sand trap, probably a drop of 25 feet,” he remembered. “I deeply regret that.”

Broken leg and all, coach Allen started Tettelbach in center field against Harvard. “To win a letter, you had to play a certain number of games or play in the Harvard or Princeton game,” Tettelbach said. “All I could do was waddle out and stand there. That first hitter knew. Quinn threw a curveball and he tried to go to right. He fouled it off. One pitch and we were out of there but we got our letter.”

Tettelbach, who shared the Blair Bat, symbolic of the Ivy League batting title, with teammate Jerry McCarthy, stayed home as the likes of Bush and Quinn ended their college careers in a losing effort against the University of Southern California in the College World Series. Quinn, Moher, Matthews, and Felske all signed pro contracts. “Quinn was just exceptional,” Tettelbach said. “He got $60,000 and a new car to sign with Red Sox.”

With Tettelbach now leading off, Yale struggled to stay above .500 the next two seasons, although he fondly recalled the Big Three Alumni Day battles against Harvard and Princeton that traditionally drew huge crowds. As a junior, he played in Yale’s 100th baseball victory over Harvard, a 3-0 win at Yale Field. A few days later, after a 4-3 win over the Crimson in Cambridge before 8,000, the 19-year-old Tettelbach was elected captain for 1950.

That season Yale defeated Harvard again, 2-1 on June 19, but the Crimson humiliated the Elis, 12-3, a few days later in Cambridge – Tettelbach’s final game.

He headed north to play for Rutland in Vermont’s Northern League. “Marty Jones, the Rutland manager, was also a Philadelphia Athletics scout,” Tettelbach said. “He wanted to sign me but the A’s wouldn’t give him $500. Finally the Yankees came through. Harry Hesse signed me – $500 to sign, $500 if you were still around on September 1.”

At Joplin, Missouri, of the Class C Western Association in 1951, Tettelbach batted .318 with seven home runs and 72 stolen bases under manager Bill Holm. He also developed a lifelong friendship with a 19-year-old outfielder, Whitey Herzog, then in the early stages of his Hall of Fame career. “I taught Whitey a little trick,” Tettelbach said. “I remember the outfield grass often got very high at St. Joseph [a rival team]. I told him to put a ball in your pocket. When the ball goes into the gap, run to it, reach in your pocket and fire it in. We cut off a few runs that way.”

Depending on the pitcher, Tettelbach and Herzog alternated at batting second and third at Joplin. When one got on second base, the guy at the plate would bunt up the third base line. Both umpires would watch the play, the runner going up the line. With nobody watching third, the guy coming from second could often cut inside the bag by several feet. “We did stuff like that all the time,” said Tettelbach.

Tettelbach served as a spring training baserunning coach when Herzog managed the St. Louis Cardinals.

His next stop after Joplin was Norfolk of the Class B Piedmont League, in 1952. he hit .317 with six home runs, 85 RBIs, and a league-leading 30 stolen bases for a Mayo Smith-managed team that is ranked 34th on the greatest minor-league teams list as compiled by SABR historians Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright. (The list can be found on the minor leagues’ website, minorleaguebaseball.com.) A bad back slowed Tettelbach at Class A Binghamton (Eastern) in 1953 (.252 in 122 games), but he was back in the swing at Double-A Birmingham (Southern Association) in 1954, hitting .326 with 12 home runs, again under Mayo Smith. Tettelbach said he thought he deserved a shot at the major leagues and was disappointed when he learned he would be assigned to Triple-A the next spring.

Concerned with his lack of arm strength, the Yankees thought of making Tettelbach a second baseman. In the team’s rookie camp he worked with Art Mazmanian, the shortstop on the Southern Cal team that beat Yale in the 1948 College World Series. “Mazmanian was a hotshot infielder and they put me under his care,” Tettelbach remembered. “I played second and Maz short in rookie camp. Casey loved it. ‘How many double plays did Yale and Southern Cal make today?’ he would ask.”

But when the 1955 season began at Triple-A Denver, Tettelbach was still an outfielder, playing for Ralph Houk, who was making his managerial debut. A dozen members of that team – catcher Darrell Johnson, infielders Marv Throneberry, Bobby Richardson, Woody Held, and Herb Plews, outfielders Jim Fridley, Lou Skizas, and Herzog, and pitchers Wally Burnett, Rip Coleman, Don Larsen, and Ralph Terry – made the majors. The team, which finished in third place, drew 426,248 fans, a thousand better than the Washington Senators.

After being traded to the Senators before the 1956 season, Tettelbach “had a hell of a spring,” he said. After hitting .388 in about 30 games he “knew I had the job a week before the season started.”

He was going from Casey Stengel to Chuck Dressen. “They had the same upbringing, formally uneducated,” Tettelbach said. “Through growing up and maturing, Stengel became a great man and Charlie Dressen, quite frankly, never made it. He was jealous, egotistic, not capable of sharing the limelight with anybody. If Charlie was on, nobody better get in his way. Casey, on the other hand, loved college kids, loved everybody. He always gave you the time of day, always pumped you up, made you feel like you were the important guy. There was a marked difference between the two.”

He recalled being taken to the Washington Touchdown Club along with Eddie Yost and Dressen to discuss the coming season. “I told a few more jokes and got a few more laughs than Charlie did and I don’t think it sat well with him,” Tettelbach said.

Still, he was the starting left fielder. Although he had some moments – a game-winning single against the Baltimore Orioes on April 19, topped by a triple, a sacrifice fly, and a bases-loaded walk three days later in an 8-4 win over Baltimore – on he was hitting a paltry .156 after 64 at-bats. On May 13 he was shipped out, returning to Denver.

“After the spring I had, after one month of not going so hot, I really felt I got short shrift,” he said. “I was shipped back to the minors and never came out it.” He hit .250 in 74 games with Denver, with two home runs.

Back with the Senators in 1957, he hung around for a month (2 hits in 11 at-bats) and was then sold to San Diego of the Pacific Coast League, part of a deal involving the Senators purchasing Bob Usher from Cleveland. He decided to call it quits.

“Ralph Kiner had something to do with it because he called me personally trying to convince me to join San Diego but I had given up at that point,” Tettelbach said. “I had two kids near school age and couldn’t travel all over the country any more. And I had something to come back to.” He went to work for the Copeland Company, a manufacturer of asphalt. He also became a major force in the Connecticut State Golf Association as both a player and official. A six-time Yale Golf Club champion, he served on the Golf Association’s executive committee for 25 years, and was its president in 1991-92. Tettelbach earned a spot in the CWGA Hall of Fame. The CSGA Player of the Year Trophy bears his name.

After retiring from Copeland Tettelbach maintained his involvement with the Connecticut State Golf Association and the Yale Golf Club. Eventually he moved to East Harwich, Massachusetts, where he died on May 5, 1995, of heart disease.

Tettelbach had no regrets about his baseball career. “I was not a bad hitter,” he offered 30 years after leaving the game. “I was a good hitter in the clutch although I couldn’t hit with power. I could run like hell. I had a lousy arm but I was a good fielder. But I wouldn’t trade any of it.”

April 4, 2011

Sources

Much of this biography is based on an interview with Dick Tettelbach in the fall of 1990. The interview is part of SABR’s oral-history collection at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Full Name

Richard Morley Tettelbach

Born

June 26, 1929 at New Haven, CT (USA)

Died

January 26, 1995 at East Harwich, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.