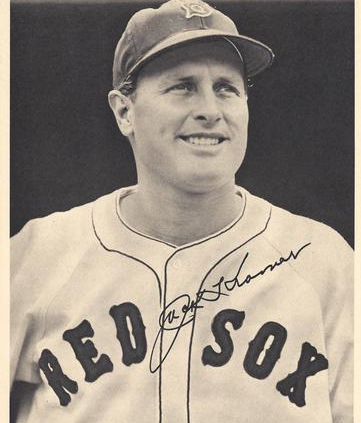

Jack Kramer

After winning the American League pennant by 12 games in 1946, the Boston Red Sox had slipped to third in 1947, finishing 14 games behind the champion New York Yankees and two games back of the second-place Detroit Tigers. In an attempt to improve their hitting and pitching, the Red Sox pulled the trigger on a blockbuster trade with the St. Louis Browns on November 17, 1947, acquiring 29-year-old right-handed starting pitcher Jack Kramer and slugging shortstop Vern “Junior” Stephens in exchange for seven players (catchers Roy Partee and Don Palmer; pitchers Al Widmar, Jim Wilson, and Joe Ostrowski; infielder Eddie Pellagrini; and outfielder Pete Layden) and a reported $310,000 cash.1

Both Kramer and Stephens responded with terrific years and were key ingredients in the Red Sox’ chase for the pennant in 1948, which they lost in a one-game playoff against the Cleveland Indians. Kramer became the team’s leading winner, compiling a record of 18 wins and only five losses, including a clutch 5-1 victory over the powerful Yankees on the last weekend of the season. It was Kramer’s career year and last real hurrah. Plagued by a sore arm, he won only six games while losing eight in 1949, when the Red Sox again fell just short of the pennant.2 Eventually released by the Red Sox, he pitched in four games for the 1951 New York Giants, his last season in the major leagues.

At the time the Red Sox acquired Kramer, he was a 12-year veteran of professional baseball and had pitched for the Browns since 1939. He was born on January 5, 1918, in New Orleans and grew up there. By 1934 Jack was the catcher for the Skelly Shamrocks, his American Legion team, until he tried pitching one day in the second game of a doubleheader. He threw only fastballs and had no real windup, but a three-hit shutout was the result. Thereafter Kramer was mostly a pitcher. During his last year at Warren Easton High School, he caught the first game of the season but pitched thereafter, losing only one game. His mound prowess caught the attention of Lenny Mock, a New Orleans native who managed the Lafayette White Sox of the Class D Evangeline League, an affiliate of the Browns.

Mock arranged a tryout and signed Kramer for the 1936 season. Jack was raw and wild and Mock came close to releasing him. Ray Cahill, a Browns scout, saw something in Kramer, however, and urged patience. He worked with Kramer and changed his delivery to overhand from his previous herky-jerky three-quarters delivery. Kramer finished the year with seven wins and 11 losses and an unattractive 5.59 earned-run average but was signed nonetheless for 1937. There the virtue of patience showed itself as Jack improved to 12-9 and dropped his ERA 2½ runs to 3.03 to help Lafayette into a tie for the pennant with the Rayne Rice Birds. He struck out 147 batters in 175 innings and was rewarded with a late season call-up to the Des Moines Demons in the Class A Western League.

Kramer advanced to the San Antonio Missions of the Texas League for 1938 and, only 20 years old, won 20 games while losing 11. In 242 innings he allowed only 201 hits and put together a sparkling 2.49 earned-run average. His great performance in the fast Texas League earned him promotion to the woeful St. Louis Browns for the 1939 season. The ’39 Browns, under rookie manager Fred Haney, who almost 20 years later led the Milwaukee Braves to two pennants and a world championship, could win only 43 games while losing 111 and finishing deep in the American League cellar, a whopping 64½ games out of first place. Kramer’s nine wins tied Vern Kennedy for the club lead. He also suffered 16 defeats and his earned-run average was an unsightly 5.83, which nonetheless was slightly below the team’s 6.01 ERA. His strikeout-to-walk ratio was a backward 1-to-2, with only 68 strikeouts and 127 walks. He still showed promise, throwing two shutouts and pitching 10 complete games.

Kramer struggled even more in 1940, going 3-7 with a 6.26 ERA before the Browns shipped him to Toledo of the American Association. He wasn’t any better with the Mud Hens, finishing with a 1-6 won-lost record and an unhealthy 6.86 ERA. The pitching-deprived Browns gave him another shot in 1941 and he compiled a 4-3 record in 29 games, all but three in relief. Still plagued by wildness, Jack walked 40 and struck out only 20 in 59⅓ innings while his ERA remained above five. Kramer roomed with utility infielder Ellis Clary at the Melbourne Hotel in St. Louis during the 1941 season and Clary recalled that Jack called his mother in New Orleans every night.

With World War II on in full force, Kramer spent 1942 working as a shipfitter at the Delta Shipyard in New Orleans, where he was able to pitch an occasional Sunday semipro game. Then he enlisted in the Navy in January 1943 and volunteered for the rigorous Seabee training at Camp Peary in Virginia. His sinuses, which had first been a problem in Toledo in 1940, kicked up with all the plunging in and out of water in Virginia’s marshlands that was required of him, landing him in the post hospital. After a month’s stay there, the Navy gave him an honorable discharge on May 14 and he headed home to New Orleans to further recuperate.

Kramer rejoined the Browns on June 22, 1943, and appeared in three games as he worked his way back into pitching shape. The Browns played an exhibition game on August 5 with Toledo, still their top minor-league affiliate, and left Kramer with the Mud Hens. It was a wise decision, for there, in his second stint in Toledo, Jack turned his career around and never looked back. After losing his first start to the Kansas City Blues, 3-1, he reeled off eight straight wins, including two-hit and three-hit shutouts. He even topped those performances on September 11 when he threw a no-hitter against the Louisville Colonels. He finished with an 8-2 record and an impressive 2.46 ERA. Improved control helped immeasurably; Kramer struck out 59 and walked 26 in 84 innings of work.

The 1943 Browns had finished in sixth place with an uninspiring 72-80 record. In 1944, however, the baseball gods looked down with favor on the historically hapless franchise. With World War II at its peak, the Brownies’ roster was favored with a number of 4-Fs who were front-line players, including Vern Stephens, George McQuinn, and Al Zarilla.3 In addition, they had three key players who had been discharged from the service – Kramer, Frank Mancuso, and Sig Jakucki, who was working as a paper hanger in Houston when the Browns signed him.4

The Browns entered the season with uncertain pitching, to say the least. Manager Luke Sewell selected Kramer to pitch the April 17 opener against the Tigers in Detroit even though his lifetime record was 16-26 and his earned-run average was close to 6. But Jack was superb, beating Dizzy Trout 2-1 and shutting the Tigers out until Pinky Higgins’ hit a home run with two out in the ninth. That win was the first of nine straight Brownie victories to start the season, blowing by the Yankees’ record set in 1933 of seven straight wins to open a season. Besides the opener, Kramer won the fifth and ninth of those victories, defeating the White Sox 5-2 while hitting a two-run homer over the 402-foot sign in left-center and conquering Cleveland, 3-1. It was Kramer’s first home run since 1939 and one of five he hit during his career.

The Browns stayed in first place until May 14, when the Yankees took over, but eight days later St. Louis reclaimed the lead. They were in and out of the lead, embroiled in a tight pennant race with up to four teams. Kramer won five in a row to start the season before slumping. At the All-Star break the Browns were 45-34 and in first place by 2½ games. They won 10 in a row in late July and early August to open a 6½-game lead over the Yankees, but by Labor Day had surrendered the lead to the New Yorkers. Although the Browns briefly slipped to third place in early September, they refused to wilt and showed the resiliency necessary to hang in there.

On September 16 Kramer threw a one-hitter at the White Sox to propel the Browns back into the lead. It was short-lived, however, as the next day the Tigers won a doubleheader over Cleveland while the Athletics swept two from New York to regain the lead. Heading into the final weekend of the season, the Browns found themselves one game behind the Tigers, with four games slated against the tough Yankees at Sportsman’s Park while Detroit hosted the cellar-dwelling Senators. Kramer pitched the crucial first game of the Friday doubleheader and prevailed 4-1, contributing a key double to the Browns’ offense. The Browns, behind continued outstanding pitching, went on to sweep the Yankees while the Tigers could only split their four games with Washington. The Browns’ performance vaulted them by a single game to their first and only pennant.

Waiting for the Browns in the World Series were the powerful (by wartime standards at least) St. Louis Cardinals, who had won 105 games and swept to the National League pennant by 14½ games. The teams split the first two games and Kramer started the pivotal third game against rookie Ted Wilks for the Cardinals. Wilks had broken in with a bang, winning 17 while losing only 4, but the Browns drove him from the mound with four runs and five hits after two were out in the third. Kramer pitched a strong game, striking out 10 and allowing only two unearned runs to win 6-2 and propel the Browns into a two-games-to-one lead.

Unhappily for the Brownies, the Cardinals then won three straight to win the Series, four games to two. Kramer pitched two scoreless innings in a losing cause in Game Six to bring his series total to 11 innings and a perfect 0.00 earned-run average. For the regular season he had won 17 and lost 13, with a sparkling 2.49 ERA in 31 starts and 257 innings.

Kramer held out until late March the following spring, looking for a $5,000 raise. He got something less than $3,000 but still started the season strong, winning his seventh game in mid-June. Thereafter a groin injury hampered him but he tried to pitch through it. Jack finished 10-15 for the season, but with a solid 3.36 ERA. The drop-off in his performance, however, certainly had an impact on the Browns, who finished in third place with an 81-70 record, six games behind the Tigers. It may also have had something to do with the fact that Kramer was tipping his pitches and at least the rival Tigers picked it up. According to the Tigers’ Les Mueller and Red Borom, Kramer turned his glove one way when he threw his fastball and another when he threw his curve, making it easy for the batter to know what pitch was coming.5

Kramer was not above enjoying himself in the dugout and did a mean Bugs Bunny imitation. One-armed outfielder Pete Gray played for the Browns in 1945 and, according to teammate Ellis Clary, Kramer would sit in the dugout and in his best Bugs Bunny voice say, “Eh, don’t look now, Doc, but there’s a one-armed man out there in center field.” Everyone on the bench would crack up and later, when it was quiet, Kramer would repeat the line in case anyone had missed it.6

In the spring of 1946 the Browns attempted to cut Kramer $2,000, evoking an angry reaction from Jack, who indicated that the club was fully aware of his injury the previous year. He ended his holdout on February 27 and joined the club for spring training in Anaheim, California. The Browns struggled from the start and won only 66 games, finishing in seventh place, 38 games out of first. Kramer was one of the few bright spots, leading the team with 13 wins against 11 losses with three shutouts and a 3.19 ERA. In May and June the Yankees repeatedly tried to acquire Kramer but the Browns would not let him go. He was selected to the American League All-Star team for the only time of his career. All-Stars manager Steve O’Neill tabbed Kramer to pitch the last three innings of the 12-0 American League laugher in Fenway Park and he responded with three hitless innings, striking out Phil Cavarretta, Marty Marion, and Del Ennis in the process.

Kramer had Hollywood-good looks and by now had a reputation as a clotheshorse. It was said that he couldn’t pass a mirror without stopping to admire himself. He apparently also had quite a pair of rabbit ears. One afternoon in 1944 the Indians, led by one of their coaches Del Baker, were quickly on his case, giving him a considerable going over from their dugout. In the second inning, Kramer plunked player-manager Lou Boudreau in the ribs with a fastball. As Boudreau trotted to first, Jack strolled over toward the first-base line and said, “If you don’t keep those guys on the bench quiet, I’ll stick one in your ear the next time you come to bat. You’re the boss so let’s see you shut them up.”7

Kramer was well known for his competitive drive and generally did not like to be removed from games he started. Once when Browns manager Luke Sewell took him out of a game against the Red Sox in Fenway Park, Kramer became so mad that he fired the ball far up into the stands. One wag remarked that it was his best throw of the day.

The 1947 Browns continued the team’s slide, this time falling all the way to the American League basement. The club, under Muddy Ruel, could win only 59 games. They were led by Kramer’s 11 victories, the only Brownie hurler with double-digit wins. But Jack lost 16 times and his earned-run average was an unsightly 4.97. For the first time since 1943 he walked more men than he struck out and gave up more hits than innings pitched. Even so, he was named to the All-Star team, although he did not pitch in the game.

One of Kramer’s teammates on the Browns was the equally temperamental Jeff Heath, a burly outfielder who would play a key role for the 1948 Boston Braves pennant winners. Heath and Kramer were not shy about agitating each other about poor performances during that long, losing season. Before a game in Detroit, Kramer complained to Heath about poor offensive support and Heath reminded Kramer about how many times he had been knocked out of the box recently. Finally Heath said, “Okay, we’ll get you a three-run lead today. Let’s see if you can hold it.”

Heath proceeded to go 1-for-3 but John Berardino drove in three runs with a bat comedian Joe E. Brown had just given him. Kramer did his part, pitching a four-hit shutout to beat Detroit 3-0.8

After winning the 1946 pennant, the Boston Red Sox had slipped to third place in 1947, finishing 14 games behind the Yankees. Shortly after the season, the team named the veteran skipper Joe McCarthy manager, with Joe Cronin moving upstairs to general manager. The new brass did not waste much time shaking up the roster. Before Thanksgiving, the Red Sox outbid the Indians and made two deals in two days with the financially strapped Browns, first securing Kramer and slugging shortstop Vern Stephens for six players and a reported $310,000, then the next day acquiring pitcher Ellis Kinder and infielder Billy Hitchcock. With starters Tex Hughson, Dave (Boo) Ferris, and Mickey Harris all nursing sore arms and contemplating surgery, the Red Sox counted on Kramer to step into the starting rotation in 1948.

It didn’t begin well for Kramer, who reported to spring training recovering from the flu, which had inflamed his back. He also suffered with what was described as a “bad leg.” In any event, he was not able to make his first start for the Red Sox until May 1, defeating the Yankees 8-6. After losing his second start to Detroit, 8-3, Kramer threw a six-hit shutout against the White Sox on May 11, winning 8-0. But two rough outings followed and with the Red Sox thrashing around in seventh place, Joe Cronin reportedly put Kramer on waivers. It is uncertain whether no one claimed him or whether the Red Sox revoked the waivers, but Kramer remained with the Red Sox. It is often said that some of the best deals are the ones teams do not make, and keeping Kramer was a prime example of that maxim. He proceeded to reel off 11 straight victories through early August to propel Boston into pennant contention. Although passed over for the All-Star team, at the end of his streak Jack’s won-loss record stood at 13-3.

At some point during his streak, Kramer went on a clothes shopping spree. According to teammate Birdie Tebbetts, in a story that may be apocryphal, Kramer announced in the clubhouse that he had just purchased two suits, half a dozen trousers, and four sport coats. The clothes were being altered and he couldn’t wait to show them off. He said, “Best looking set of clothes you’ll ever see, but you bunch of hillbillies wouldn’t know the difference, so what the hell.”

On the day Kramer picked up his new clothes from the tailor, Tebbetts told Ted Williams, “Kramer is coming in soon and he’ll be wearing his new clothes. No matter what I say to him, I want you to agree with me.” Ted said, “OK, I’ll do it.”

Shortly Kramer did come waltzing in decked out in a flashy sport coat and greenish trousers with a knife crease. He stood in the middle of the clubhouse with all eyes on him and turned in a circle with his chest out and said, “All right you assholes, what do you think?”

Tebbetts went up to Jack, felt the material, and said, “Gee, they are beautiful, Jack. Must have cost you a fortune. What do you think, Ted?”

Williams said, “Yeah, they’re beautiful, Birdie. Must have set him back a pile of dough.”

Then Tebbetts stood back and frowned and said, “Wait a minute, Jack. The left sleeve is longer than the right.”

Williams said, “Yeah, you’re right Birdie. They are uneven.”

Then Tebbetts reached up and adjusted Kramer’s collar and said, “Jack, your collar is riding up.”

Williams came up and looked at it and said, “That’s right, Birdie, but have you looked at the trousers? The cuff is riding too high.”

Kramer walked to the mirror, staring at his cuffs and turning this way and that while his teammates were muffling laughter. Finally, he stomped off cussing out his tailor while his teammates guffawed behind him.9

On August 3, with his winning streak still intact, Kramer was forced to leave a start against the Browns in the third inning with a sore shoulder, but under the rules then in place was credited with the victory, his 11th in a row. After a no-decision against the Yankees seven days later, Kramer lost to the Senators 5-4 on August 14 to end the streak. On August 20 he beat the Senators 10-4 to bring the Red Sox within three games of the league lead. His arm, however, was clearly bothering him. He lost to the White Sox in a short outing on August 27 and at one point threw only three innings in an 11-day stretch before beating the Tigers 10-1 on September 1 to record his 15th win of the season. The win kept the surging Red Sox in front of the pack by a single game in one of the tightest pennant races in history.

On Labor Day, four days later, Kramer threw another strong game, defeating the Senators in Washington 2-1 on a four-hitter to complete a sweep of a doubleheader. The win ran Jack’s record to 16-4 and kept the Red Sox a game ahead of the Yankees and 4½ games in front of the Indians. Joe McCarthy then tabbed Kramer to start at home against the Yankees on three days’ rest but the Bronx Bombers chased him in the sixth on their way to a 6-2 lead. The Red Sox came back to tie the game 6-6 in the eighth inning before Joe DiMaggio’s grand slam in the tenth inning won it for New York and cut Boston’s lead to 2½ games.

Kramer’s next start was shaky as well. On September 14 he lasted only into the third inning and left trailing 4-1 in what was eventually a 17-10 loss to the White Sox. The blowout defeat cut the Red Sox’ lead over the Yankees to a single game. Three days later in Detroit Kramer tried again in the second game of a doubleheader and was again knocked from the box early, this time after 3⅔ innings while behind 6-3 in a game Boston was to lose 8-6. It was his third unsuccessful try for his 17th win and enabled the Indians to climb within a half-game of the lead with the Yankees only a game back.

By the time of Kramer’s next start, on September 25, the Indians, Yankees, and Red Sox were in a dead heat, all three with 91-56 records. On a Saturday afternoon before 66,500 in Yankee Stadium, Kramer hooked up in a crucial game against Allie Reynolds, also seeking his 17th win of the season. The Red Sox scored two runs in the first without a hit, thanks to two Yankee errors, and, buoyed by great defense, Kramer pitched a complete-game 7-2 victory. The Indians kept pace behind Gene Bearden with a win over Detroit.

Kramer’s next and final start came on Saturday, October 2, in the Red Sox’ 153rd game of the season. It was also against the Yankees, this time in Fenway Park, with both clubs one game behind the Indians with two to play. Cleveland was playing its last two games against Detroit in Cleveland, knowing that the pennant race could not be decided until all three teams had completed the 154-game season. But the loser of Saturday’s Red Sox-Yankee contest would be virtually out of the race.10

Facing Kramer was Tommy Byrne, a southpaw who had defeated the Red Sox 6-2 the previous Sunday. In the first, Kramer retired leadoff hitter Phil Rizzuto but allowed a single to right by Tommy Henrich. Bobby Brown, who had tripled and doubled against the Red Sox the previous weekend, got hold of one but Dom DiMaggio was able to track it down in deep center field. Kramer then bore down and struck out Joe DiMaggio to end the inning. It was only DiMag’s 30th K of the season.

The Red Sox struck quickly in the bottom half of the inning as Byrne walked Johnny Pesky with one out and Ted Williams deposited a fastball into the bullpen in right for a 2-0 lead. In the third Pesky walked again and Williams doubled him to third. Stan Spence singled sharply to right to score both and stretch the lead to 4-0. Boston tallied another run in the fourth on a fly ball by Vern Stephens to bring the score to 5-0. Meanwhile Kramer had retired 12 Yankees in a row until Tommy Henrich’s single in the sixth. New York finally scratched out a run in the seventh on a double by DiMaggio, a groundout by Berra, and a sacrifice fly by Johnny Lindell.

The 5-1 win was Jack’s 18th of the year against only five losses and knocked the Yankees out of the pennant race. The Indians, behind Gene Bearden, defeated Detroit 8-0 to maintain their one-game lead. The next day, Sunday, the Red Sox again beat the Yankees, this time 10-6 in a seesaw ballgame, while Detroit knocked Bob Feller from the box to win 7-1 and drop Cleveland into a tie with the Red Sox.

The playoff game was the next day, Monday, and if Kramer was to pitch it would be with only one day of rest. According to a report in The Sporting News, Joe McCarthy looked to his veteran right-hander to start the playoff game but Kramer did not respond positively.11 His season was over, as the Red Sox went with the veteran Denny Galehouse and Cleveland, behind the remarkable Bearden, won the playoff and the pennant, 8-3.

Kramer had been instrumental in lifting the Red Sox into the pennant race and had won two huge games at the end of the season to give his team a chance to win it all. His winning percentage of .783 led the American League. For the year he threw 205 innings in 29 starts and 14 complete games. His 233 hits allowed and 4.35 earned-run average attest to the fact that he received excellent offensive support when he pitched. But the fact remains that without his winning streak early in the summer and clutch wins in the last week of the season, the Red Sox would have not tied for the pennant.

Kramer parlayed his memorable 1948 season into a $30,000 contract for 1949, one of the top salaries on the team. In spring training he apparently won a contest for the best-dressed player on the team, a title he savored. He was called Handsome Jack or Alice by his teammates, the latter because he wore only silk underwear that he insisted on washing himself. One story that made the rounds was that Kramer had bought one suit because the salesman told him it was the only one of its kind in the world. When he later saw someone else wearing the same suit, he gave his away. He was so enamored of his wardrobe that he sometimes would change clothes two or three times a day, leading teammates to call him “a fruit basket.”

Teammate Matt Batts remembered Jack as an inveterate complainer who was very picky about everything. For example, he would always send his food back in a restaurant if it didn’t suit him. Batts’s locker was next to Kramer’s in the Boston clubhouse. One afternoon Batts came in and found his sports jacket on the floor. He asked Ellis Kinder, whose locker was on the other side of his, how it got there. Kinder told Batts that Kramer had tossed it down because he didn’t like it that the sleeve of Batts’s jacket protruded into Kramer’s adjoining locker.

When Kramer came in to the clubhouse, Batts confronted him and Jack admitted to throwing Batts’s jacket on the floor because the sleeve was hanging over into his locker. Batts bided his time and a few weeks later Kramer wore his white cashmere sports coat to the ballpark. After he hung it in his locker and went onto the field, Batts grabbed it, threw it across the clubhouse floor and left it there. When Kramer came in the two almost came to fisticuffs.12

Later, Red Sox coach Mike Ryba was known for his selection of an American League All-Ugly Team each year. His selections were the cause of much anticipation and discussion among the league. More than once Ryba picked Kramer to his all-ugly team, just to bring him down a notch or two.

Jack struggled mightily in ’49 with a sore arm and at the All-Star break had an 0-4 won-lost record. The Red Sox hung tough with the Yankees even without Kramer, thanks to great years from Ellis Kinder and Mel Parnell on the mound and astounding offensive production from Ted Williams, Vern Stephens (each of whom drove in an eye-popping159 runs), and Bobby Doerr. After a mediocre start, the club went 45-10 from July 5 through the end of August to come within two games of New York. Kramer had a brief resurgence in August, going 3-1 for the month.

Handsome Jack was known to show off from time to time. During the season he asked catcher Batts to warm him up in front of the dugout before a night game on an evening when he was not scheduled to pitch. Batts was not very happy about it since warming Kramer up would cause him to miss batting practice. The crowd was filing in and Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey and other executives were nearby. Batts thought Kramer was exaggerating his motion and preening for the audience a little more than necessary. As Jack delivered a pitch, Batts dropped his catcher’s mitt and caught the ball barehanded. Batts returned the ball to Kramer but Jack made no effort to catch it. Instead he just turned around and walked away. It was the last time Kramer asked Batts to warm him up.13

The Red Sox again lost a taut pennant race, this time on the last day of the season, 5-3 to the Yankees on a home run and an RBI groundout by Tommy Henrich and a three-run double by Jerry Coleman. Kramer struggled to a 6-8 record and a dismal 5.16 ERA. He threw only 111⅔ innings and could start only 18 games.

Joe McCarthy was clearly tired of Kramer’s act and in March 1950 the Red Sox sold Jack to the New York Giants for a reported $25,000. Under the rules then in place, all the American League clubs had to pass on Kramer for him to be sold to the National League. Kramer had, at a minimum, his feelings hurt by being dumped by the Red Sox and lashed out at Joe McCarthy, calling him “the most ornery man I know” and accusing McCarthy of railroading him out of the league “only because he had a personal grudge” against Kramer.14 He promised that he would make McCarthy regret the sale.

By most accounts, his Boston teammates were glad to see Jack go, some referring to him as “a grand opera.” Birdie Tebbetts, the Red Sox’ regular catcher, was particularly harsh, alleging that Kramer “never delivered when we needed him. His attitude was all wrong from the time he first joined up. All he cared about the game of baseball was the money he could get out of it to buy fancy clothes and cars and strut as Handsome Jack. He didn’t really care for the game and he certainly didn’t care for anybody on this squad.”15 Another “star” teammate said, “The best thing Joe Cronin (the GM) ever did for this club was to get rid of that drone bee. Joe [McCarthy] knew what a bad influence the guy was on team morale. We have peace and harmony now that he’s gone.”

Veteran Boston sportswriter Harold Kaese labeled Kramer as temperamental, high-strung, sensitive, and self-centered.16 When Kramer learned of the quotes attributed to Tebbetts, he found it hard to believe that Birdie had said those things about him. But, Kramer went on, if Tebbetts had said those things, they were lies. A man had to defend himself, he said, and he “gave my best for Boston. I always have and always will. Man, I couldn’t sleep nights if I didn’t and I can always sleep nights.”

Kramer couldn’t understand why someone “in the same business” would talk about another like that because “it gets no one any satisfaction.” He then couldn’t resist responding to Tebbetts’ supposed quip about his wardrobe: “I don’t know why Tebbetts brought up the subject of clothes and automobiles. He has more clothes than I have and he can afford better automobiles.”

Then Handsome Jack attempted some humor, “I’ll say this about clothes. Birdie may have more clothes than I have, but mine fit me a lot better than his fit him.”17

On the other side of the deal, Giants manager Leo Durocher was sold on Kramer’s reputation as a good competitor.18 But it is unlikely that McCarthy regretted the sale. Kramer went 3-6 for the Giants in 1950 in 35 games and only 86⅔ innings. His ERA was a respectable 3.53 but he walked more than he struck out and gave up more than a hit an inning. He was used mostly in relief and as a spot starter, with nine starts and one complete game.

On August 12 Kramer cost the Giants a win on the basepaths, of all things. In a game against the Phillies in Shibe Park, Kramer found himself on first base late in a tie game. Jack Lohrke singled to right-center and Kramer only made it to second base on a play that should have sent him to third. Whitey Lockman followed with another hit and Kramer was thrown out at the plate, preserving the tie. The Giants went on to lose in extra innings. After the game, Leo Durocher was headed to Kramer’s locker to give him what-for when he found that several Giants were already there, accusing Jack of not hustling and costing them the ballgame in loud, angry voices. For his part, Kramer offered no excuses.19

Not surprisingly given his history, Kramer held out in the spring of 1951, balking at a proposed pay cut. The Giants and Durocher found it amusing that someone who had won three games was holding out and made it clear that they really didn’t care much if he signed or not. Kramer did sign on March 7, accepting a $15,000 salary, a reduction of $3,000 from the previous year. He reported to spring training but it was not long before he got himself into the doghouse. First Durocher ignored him for a week or so after he announced that he was ready to pitch, following his late reporting due to his holdout. After finally pitching two innings against the Cardinals, he reported sick for another exhibition game, claiming stomach problems. The Giants were short-handed in the bullpen at the time and the team doctor could find nothing wrong with Jack.

The next day, on the train to Mobile, Alabama, Durocher told Kramer to stop acting like a prima donna and to get ready to contribute to the team. Durocher told the press that Kramer’s problems were all in his mental approach to the game. He referred to a great batting practice Kramer had recently thrown and said, “The guy can pitch if he wants to pitch. Larry [Jansen] and I thought it was one of the greatest pitching shows we’ve ever seen.”20

Durocher must have struck a chord with Handsome Jack. On April 3, the day after his heart-to-heart talk with Durocher, Kramer threw five scoreless innings in an exhibition game against the Boston Braves, allowing only one hit. A few days later Kramer threw a complete game in Dallas against the Cleveland Indians, winning 10-3. He shut the Tribe out for six innings, running his spring-training stretch of scoreless innings to 13.

Once the season began, however, Kramer was ineffective. In four appearances, including one start, he pitched 4⅔ innings, giving up 11 hits and eight earned runs. On May 19 the Giants gave the 33-year-old his unconditional release.

That same day, Kramer walked into Yankee Stadium and asked Casey Stengel for a tryout. Casey apparently did not recognize Jack at first and thought that he was an unknown who had been sent down to the field by George Weiss, the general manager. It soon was straightened out and Kramer pitched batting practice for the Yankees. Stengel asked his players to tell him if Kramer had any stuff left and the “tryout” went on for 11 days, with Jack pitching batting practice each day. Finally on May 28 the Yankees signed Kramer and put him on the roster, sending rookie pitcher Tom Morgan down to the Kansas City Blues to make room.

One Yankee teammate Kramer knew was Bobby Brown, the third baseman. Brown had attended medical school at Tulane and become friendly with Kramer, the New Orleans native, in the offseasons. When he joined the Yankees, Brown knew that if he wanted a new suit, all he had to do was ask Kramer or Allie Reynolds and they would come along and buy three suits to his one.21

Kramer could not regain his mound form. He appeared in 19 games for the Yankees, starting three, while compiling a 1-3 record and a 4.65 earned-run average. The Yankees, headed for their third straight American League pennant, ultimately decided that Jack wasn’t going to help them. The world champions released him on August 30, ending his big-league career. He gave baseball another brief fling in 1952, appearing in six games for the Dallas Eagles in the Texas League.

Handsome Jack returned to his native New Orleans, where he eventually worked selling milk, which he believed was “the greatest food in the world,” to grocery chains. In 1959 he attempted a baseball comeback at the age of 41, pitching in six games for the hometown Pelicans. He was elected in 1967 to the prestigious Diamond Club of New Orleans. Kramer died in Metairie, Louisiana, on May 18, 1995, of a brain hemorrhage at the age of 77.

In 12 big-league seasons, Kramer won 95 games and lost 103 and thus ended up a sub-.500 pitcher. His career earned-run average was an unimpressive 4.24, he walked more men than he struck out, and gave up more than a hit an inning. But he helped the St. Louis Browns to their only American League pennant and was a driving force in the Red Sox’ near run to the 1948 pennant.

Probably the best dresser in the game, Jack could be a persnickety and difficult teammate. He seemed to wear out his welcome, particularly when he was not pitching well. He struggled with arm trouble for much of the end of his career and his attitude was often suspect. He likely did not make the most of his considerable ability but he certainly left lasting impressions in Red Sox and Browns baseball history. When he was on, he was a very good pitcher and often delivered clutch wins for his teams.

An updated version of this biography appeared in “The Team That Time Won’t Forget: The 1951 New York Giants” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and C. Paul Rogers III. It originally appeared in “Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948” (Rounder Books, 2008), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Borst, Bill, Still Last in the American League – The St. Louis Browns Revisited (West Bloomfield, Michigan: Altwerger & Mandel Publishing, 1992).

Golenbock, Peter, Fenway – An Unexpurgated History of the Boston Red Sox (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1992).

Golenbock, Peter, The Spirit of St. Louis – A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns (New York: Avon Books, Inc., 2000).

Halberstam, David, The Summer of ’49 (New York: William Morrow & Co., Inc., 1989).

Heidenry, John, and Brett Topel, The Boys Who Were Left Behind (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006).

Kaiser, David, Epic Season – The 1948 American League Pennant Race (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1998).

Levy, Alan H., Joe McCarthy – Architect of the Yankee Dynasty (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2005).

McDermott, Mickey, with Howard Eisenberg, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Cooperstown (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2003).

Mead, William B., Even the Browns – The Zany, True Story of Baseball in the Early Forties (Chicago: Contemporary Books, Inc., 1978).

Smith, Burge, Nine Old Men and One Young Left Arm – A Journey Back Into the History of the 1945 Tigers (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc.,2010).

Tebbetts, Birdie, with James Morrison, Birdie – Confessions of a Baseball Nomad (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2002).

The Sporting News, various issues 1939-51.

Jack Kramer file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York.

Notes

1 One day later the Red Sox raided the struggling Browns again, acquiring right-handed starter Ellis Kinder and infielder Billy Hitchcock for pitcher Clem Dreisewerd, infielders Sam Dente and Bill Sommers, and another $65,000 in cash.

2 In 1949 Vern Stephens would top his 1948 numbers (29 home runs, 137 runs batted in) with one of the best years ever recorded by a shortstop (39 home runs and 159 RBIs).

3 Eighteen of the 1944 Browns’ 33-man spring roster were classified 4-F, the most in major-league baseball. Thirteen 4-Fs ended up playing for the Browns the entire season. Bill Borst, Still Last in the American League – The St. Louis Browns Revisited (West Bloomfield, Michigan: Altwerger & Mandel Publishing, 1992), 67.

4 The ’44 Browns listed 15 players serving in the armed forces but only two, Walt Judnich and Steve Sundra, were considered regulars. In contrast, for example, the Yankees had lost every starter from their 1942 world-championship team to the military. William B. Mead, Even the Browns – The Zany, True Story of Baseball in the Early Forties (Chicago: Contemporary Books, Inc., 1978), 118-19. Even so, the Browns won the pennant with only 89 wins in the watered-down American League, the fewest wins by a pennant winner since the war-shortened 1919 season.

5 Burge Smith, Nine Old Men and One Young Left Arm – A Journey Back Into the History of the 1945 Tigers (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2010), 63-64…

6 Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis – A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns (New York: Avon Books, Inc., 2000), 298, 314.

7 The Sporting News, February 12, 1947, 28.

8 The Sporting News, September 17, 1947, 16.

9 Birdie Tebbetts with Morrison, James, Birdie – Confessions of a Baseball Nomad (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2002), 95-96.

10 The loser of the Red Sox-Yankees game on Saturday would have to hope that Cleveland dropped both games with Detroit. Then it would have to win on Sunday to force a three-way tie.

11 The Sporting News, March 22, 1950, 20.

12 Peter Golenbock, Fenway – An Unexpurgated History of the Boston Red Sox, 174-75.

13 Golenbock, Fenway, 175.

14 New York World Telegram and Sun, February 27, 1950, 22.

15 The Sporting News, March 22, 1950, 20.

16 The Sporting News, March 8, 1950, 3.

17 The Sporting News, April 5, 1950, 36.

18 The Sporting News, March 8, 1950, 9.

19 The Sporting News, August 30, 1950, 12.

20 Unidentified newspaper clipping dated April 3, 1951, from the Jack Kramer file at the National Baseball Library, Cooperstown, New York.

21 Telephone interview with Dr. Bobby Brown, September 11, 2007.

Full Name

John Henry Kramer

Born

January 5, 1918 at New Orleans, LA (USA)

Died

May 18, 1995 at Metairie, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.