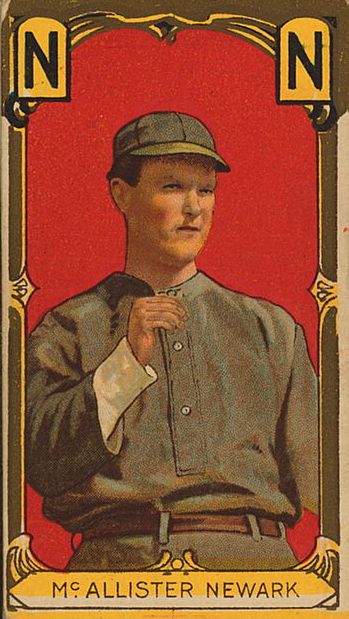

Sport McAllister

Few players in the history of our national pastime could match the versatility of the man Sporting Life magazine once referred to as “The finest all around player in the business besides Lajoie.” Lewis “Sport” McAllister was the ultimate utility man, making appearances at every position on the diamond during his 22-year tenure in professional baseball. Sport was an outstanding athlete who could do a variety of things well on the ball field. He was a fast runner and a solid defensive player with a strong throwing arm. Never a great hitter in the majors, McAllister reached the .300 mark once in seven big league seasons. The 5’ 10 180- pound switch hitter knew the game inside and out. Lew coached at the collegiate level with the University of Michigan, which led to a one-year stint as the manager of the Eastern League Buffalo Bisons.

Few players in the history of our national pastime could match the versatility of the man Sporting Life magazine once referred to as “The finest all around player in the business besides Lajoie.” Lewis “Sport” McAllister was the ultimate utility man, making appearances at every position on the diamond during his 22-year tenure in professional baseball. Sport was an outstanding athlete who could do a variety of things well on the ball field. He was a fast runner and a solid defensive player with a strong throwing arm. Never a great hitter in the majors, McAllister reached the .300 mark once in seven big league seasons. The 5’ 10 180- pound switch hitter knew the game inside and out. Lew coached at the collegiate level with the University of Michigan, which led to a one-year stint as the manager of the Eastern League Buffalo Bisons.

During the course of Sport’s major league career, he played numerous games at each position: 147 in the outfield, 83 behind the plate, 65 at first, 62 at short, 27 at third base,

7 at second and 17 on the mound, with ten complete games. Well liked and respected by his peers, a reporter once described McAllister as “A fine little gentleman and a good player.”

Lewis William “Sport” McAllister was born in Austin, Mississippi, on July 23, 1874. He was the oldest son of William J. McAllister and Maria L. (Fowler) McAllister. William was originally from Alabama and served in his home state’s 15th Infantry Regiment during the Civil War. After the surrender, the McAllisters lived in Mississippi for a short time before settling in Fort Worth, Texas. William first took a job as a clerk at a sewing machine factory and later went to work in a local printing shop.

The 1880 census lists the McAllisters with five children in the household. The McAllisters had triplets in 1880; sadly, one of the three died young. By 1900, Sport’s mother had passed away and his father remarried. William McAllister and his new wife, Ollie May, would eventually have four more children.

As a young man, Lew learned the rudiments of our national pastime on the local lots of Fort Worth. By 1891, he was the star player for Lou Weithrop’s Fort Worth Colts, one of the best amateur nines in the city. The following season, he played professionally with three different teams in the Texas League, batting .286. Over the next few years, McAllister continued to play in the minors, pitching great ball while excelling defensively at a variety of positions.

In May of 1895, the financially troubled owner-manager of the Fort Worth Panthers, Tom Richards, offered to sell Sport, the best all around player on his team, to Little Rock. McAllister said that he would gladly accept the deal if Richards used the money from the sale to pay the Fort Worth players their back salaries, a sum of around $300. After a bit of haggling, Richards sold McAllister to Little Rock for the bargain price of $100. Later that same day, the cash-poor magnate sold the entire team to local Fort Worth businessman William H. Ward. The Panthers’ new owner was totally unaware of the McAllister deal and only found out about it after his bank notified him that a $100 check had arrived from Little Rock. Ward said in the press that he would disband the entire team before he would consent to selling McAllister for the absurdly low amount of $100.

The deal with the Little Rock club was eventually voided, and Sport was allowed to stay with the Fort Worth team. The Panthers’ most valuable player batted .341 with 157 hits, 127 runs scored and 44 stolen bases to go along with a 22-6 record in the pitcher’s box. McAllister was generally considered to be one of the best tossers in the Texas League. In addition, his outstanding pick-off move to first base completely nullified the other team’s running game.

McAllister continued to impress and by June of 1896, he was pitching great ball and hitting .321. A few weeks later, on August 8th, the Fort Worth club sold Sport and pitcher Dale Gear to the National League Cleveland Spiders for $1,000.

Sport had a tough time adjusting to major league pitching, batting just .222. However, his ability to play multiple positions, including pitcher, made Cleveland manager Patsy Tebeau realize that his young player would be a valuable asset to the team in the future. “A sure catch and a lightning arm,” the Sporting Life referred to McAllister’s defensive skills at that time.

The second-place Spiders played the National League champion Baltimore Orioles in the Temple Cup Series that was held in October of 1896. The Spiders were swept in four straight games. Sport did not see action in any of the contests.

Things didn’t get much better for McAllister with the bat during his next few years with Cleveland, and a number of injuries kept him out of the Spiders lineup. When he did play, he performed well, making a few appearances in the pitcher’s box while alternating between the infield, outfield and catcher.

During the winter months, Lew ran a printing shop in his hometown of Fort Worth, in addition to working as the treasurer of the local Opera house.

The 1899 season would be McAllister’s last in the National League. The Robison brothers, who owned the Cleveland club, bought the St. Louis franchise in March of 1899. The magnates then shipped off all of Cleveland’s star players to their new team in St. Louis. Sport and his Cleveland teammates, minus their big guns, were forced to endure the worst drubbing in major league baseball history. The Spiders, who were derogatorily referred to in the press as the Misfits, finished 84 games behind the first place Brooklyn club.

Because of his business background, Cleveland’s management utilized Sport as a ticket taker at League Park during the season. Lack of fan support eventually led to the Spiders playing the majority of their games on the road. The Spiders had a home record of 9-33, drawing a paltry total of 6,088 fans. Judging from the low attendance figures, McAllister wasn’t very busy in the ticket booth.

Lew appeared in 113 games for the last place Spiders. He played every position on the diamond, hitting .237, with a team-high 8 triples. Cleveland and three other clubs were dropped from the circuit when the National League contracted from twelve to eight teams at the end of the year.

Even after the calamitous 1899 season, Sport remained highly thought of in baseball circles. The Sporting Life of November 18,1899 noted, “McAllister of the Cleveland’s [sic] is the most versatile player in the league today.”

The following April, Sport and three other Cleveland players, whose contracts had reverted back to the St. Louis club, were sold to the Detroit Tigers of the newly formed American League. The loop wouldn’t achieve major status until the following year.

The Tigers’ new utility man did well, batting .306 and stealing 40 bases while continuing to display his versatility in the field. On July 15, Sport umpired a home game against Cleveland due to threats of violence that had been made against the scheduled umpire Joe Cantillon. All reports noted that McAllister did a credible job of officiating that day.

The American League kicked off its inaugural season in 1901. Detroit would eventually finish in third place behind Chicago and Boston. Lew put up the best offensive numbers of his big league career, hitting .301 with 17 stolen bases. Tigers manager George Stallings, taking advantage of Sport’s athleticism, played him all over the diamond: 35 games catching, 28 at first base, 3 at short, 10 at third, 5 in left field, and 6 in right.

The 1902 campaign started out on a bad note for the Tigers’ star utility player. On May 9th, McAllister, playing second base, collided with right fielder Ducky Holmes while the two were chasing down a pop fly. The force of the collision dislocated Sport’s knee, requiring the placement of a plaster cast. The injury kept McAllister on the shelf for the early part of the season.

Even with this setback, the press was still enamored with Lew’s all-around play.

The Sporting Life of June 22, 1902, compared him favorably to future Hall Of Famer Roger Bresnahan. “It’s an even thing between Roger Bresnahan and Jack [Lew was occasionally referred to in the press as “Sport” and in some rare instances “Texas Jack”] McAllister as to which is the better all around player. Either can pitch, coach or play the out and infields splendidly.”

In July, a series of unexpected events unfolded that saw Sport abruptly shipped off to the Baltimore club and then just as rapidly recalled. Orioles player-manager John McGraw’s constant feuding with American League President Ban Johnson culminated in the Birds’ fiery skipper resigning from the team in July of 1902. It was at this time that McGraw set the wheels in motion for a dubious business deal with New York Giants owner Andrew Freedman and Cincinnati Reds owner John T. Brush. McGraw, who was an Oriole stockholder, received additional shares from his business partner Wilbert Robinson when he sold his half of the Diamond Saloon in Baltimore. Orioles president John J. ”Sonny” Mahon then purchased all of McGraw’s holdings, giving him 201 of the 400 total team shares. Mahon, in turn, sold all of his interests in the ballclub to Brush and Freedman, making them the majority owners of the Orioles. Before the ink was dry on the documents, the Giants laid claim to a number of Baltimore players, as did the Reds. The unexpected back room business maneuver left the minority stockholders out in the cold, as only seven Orioles remained loyal to their contracts.

On July 17, Baltimore did not have enough players to field a team and ended up forfeiting the game to the Browns. At that time, Ban Johnson, in conjunction with the minority owners, took over the daily operations of the Oriole franchise. Johnson then wired a plea to the other clubs in the league for players to replenish the depleted Baltimore roster. The Detroit Tigers sent McAllister to the Orioles, while Washington, Philadelphia, and Chicago dispatched some of their men to the short-handed Baltimore ballclub. Sport played three games for the re-vamped Birds before the Tigers, deciding he was too valuable to give away, called him back on July 22nd while the Orioles were playing in Detroit.

In November of 1902, rumors abounded that McAllister was going to jump his Detroit contract and sign with George Stallings’ Eastern League Buffalo Bisons. In order to quash the rampant speculation in the press, McAllister went public with the following statement: “Stallings made me a good offer and raised it several times. It is a poor policy for a man to jump his contract though, and, as I had signed with Mr. Angus, [Detroit Tigers owner Samuel F. Angus], before the end of the season, I have made my mind up to stay.”

Lew spent the majority of the 1903 campaign with the Detroit Tigers. In September, Sport was farmed out to Buffalo. McAllister hit .304 for the Bisons in 14 games, playing mostly at second base, before being returned to the Tigers. The following off-season Buffalo manager George Stallings ratcheted up his efforts to acquire the veteran performer on a permanent basis. Finally, in October of 1903, Detroit consented to the deal and traded McAllister and three other players to the Bisons in exchange for pitcher Cy Ferry and outfielder Matty McIntyre.

In the early spring of 1904, Sport became the assistant baseball coach at the University of Michigan under head coach Jerry Utley, a former player at the school.

McAllister reported to the Bisons when the college baseball season ended. His ability to catch and play the infield contributed greatly to Buffalo’s Eastern League championship that year. Sport was the favorite catcher of his former Detroit teammate Rube Kisinger (24-11) in addition to playing a number of games at shortstop for Stallings’ pennant winners. He appeared in 114 games, batting .254 with 20 stolen bases.

McAllister replaced Utley as the head baseball coach at Michigan in 1905. Sport was a successful and popular leader at the school although his tough discipline did not always sit well with the team. One of his more unusual rules was that the players were not allowed to drink water during the games.

For the next few years, Lew coached college ball in the spring and played professionally in the summer with Buffalo. During that time his batting average was fair but never spectacular. Defensively, his ability to play numerous positions helped Stallings’ club win another Eastern League championship in 1906. That year, Philadelphia A’s owner-manager Connie Mack offered $5000 for McAllister and outfielder Jimmy Murray or he would give the Bisons three players and $1,000 for Lew alone. The Buffalo front office turned down the deal.

McAllister, whose permanent residence was in Detroit, spent the winter of 1906-1907 living in Buffalo. This led Bison fans to correctly assume that Sport would replace Stallings, who took a temporary hiatus from baseball, as their team’s manager in 1907. Lew resigned from his coaching position at Michigan at this time due to his early spring obligations with the Buffalo ballclub

In his first and only season at the helm of the Bisons, the club finished in second place, nine games behind Toronto. Lew penciled in his own name on the lineup card 73 times that year, playing mostly at catcher.

Sport relinquished the Bisons’ managerial role the following year and resumed his post as the head coach of the Michigan baseball team. Lew stayed on with Buffalo as a player, but injuries began to take their toll, restricting him to only 73 games in 1907 and 44 in 1908. McAllister bounced back in 1909, seeing action in 81 contests for the Bisons, but still not hitting much.

Lew started out the 1910 season with Buffalo. That year, Bisons manager Billy Smith had numerous men on his roster that played multiple positions so the 36-year-old McAllister was considered expendable. Sport did not see a lot of action early on, and in June his contract was sold to the Toronto Maple Leafs. Lew did well with the Leafs before being loaned to Montreal for a brief period and then traded to Newark for pitcher Art Mueller. Sport adapted well to his changing surroundings, playing good defense while compiling a steady .256 bating average combined between the four clubs.

The 1910 census listed Lew, his wife Gertrude, whom he in married in 1900, and their five-year-old son Lewis Jr. as living in Wayne, Michigan, near Detroit.

Sport, who had tired of the college game, resigned as Michigan’s head baseball coach in early January of 1910. A few days later, he signed with the Newark Indians for the upcoming season. When asked about his new team McAllister replied, “I’m not so young as I used to be and I am taking no chances with the lake climate any longer. The springs are cold and the falls are sometimes about as raw. I made up my mind to get on with some seaboard town and Newark was my choice. I had to make use of a deal that took me first to Toronto, but I landed finally at the place I started for.”

Lew was named captain of the Newark ballclub in the spring of 1910. Later, he filled in for player-manager Joe McGinnity after the future Hall of Famer fractured his wrist while attempting to crank start his automobile.

McAllister devised a new type of shin and knee guard during the 1911 season, giving prototypes of the equipment to his fellow Eastern League catchers. Sport’s time in Newark did not last as long as planned, and in June he was traded to Buffalo for pitcher John Vowinkel. Lew’s glove work remained consistent, but his hitting had fallen off considerably.

The veteran backstop stayed on with the Buffalo club in 1912. After he’d spent most of the year with the Bisons, Baltimore purchased his contract in early August. He joined Jack Dunn’s Orioles with the stipulation that he would be allowed to become a free agent at the end of the season. Sport played a variety of positions for Baltimore, but his age and previous injuries had finally began to catch up with him, leading to his release on September 13th. Jack Dunn thought so highly of McAllister that he paid his salary for the remainder of the 1912 season. Sport said on the day he was let go, “Dunn has treated me splendidly. My stay here has been very pleasant and I could not wish for better treatment from anyone. If Jack Dunn tells you anything, you can bet your last cent that he will live up to his word.”

An article in the Baltimore Sun expressed hope that Sport would become an umpire in the International League when his playing days came to an end. “President Barrow might pick up a valuable man in McAllister and indeed he would search the country and not find a more gentlemanly or fairer man. There is one thing for certain – wherever Mack goes he will carry with him the very best wishes of every man who has ever played in the league.”

McAllister signed with the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern League for the 1913 season. On May 17, the Crackers sold his contract to the Western League Topeka Jayhawks. Sport’s former teammate at Fort Worth, Dale Gear, was the manager of the Jayhawks, and it was his recommendation that led to him signing with the team. Reunited with his old pal, Lew seemed to regain his batting eye, hitting .308 in 99 games.

The veteran switch-hitter remained with Topeka until September of 1914. At that time, his contract was sold to the Omaha Rourkes of the Western League, where he finished out the season. (Baseball-Reference shows Lew playing with Rochester in the International League in 1914, but that player was actually catcher William Lusk McAllester.)

Sport’s catching reflexes were still fairly sharp in 1914, and he called a smart game. However, McAllister’s hitting woes returned, leading him to realize that the end of his active days on the diamond was fast approaching.

During the following winter, Detroit President Frank Navin offered Sport a job as pitching coach of the Tigers, which he accepted. In April of 1915, Navin sent McAllister to Detroit’s farm club in Lincoln, Nebraska, to fill in for manager Matty McIntyre, who had gone back east due to his mother’s illness. Lew stayed on with the Lincoln club for the remainder of the year. He served as a coach and backup catcher, appearing in 75 games, 64 of them behind the plate. Once again, his defense was steady, but he hit just .211. McAllister, who was now forty-one years old, hung up his spikes for good at the conclusion of the 1915 season after 22 years of professional baseball.

By 1918, Sport was working at an adding machine company in Detroit. As time went on, the former ballplayer, because of his past employment at the Fort Worth theatre, worked behind the scenes at various acting venues in the Detroit area. He stayed in touch with the national game by umpiring in the Sanilac County League in Michigan while continuing to work as a stage carpenter in the theatre district.

In 1949, Billboard Magazine noted that Lew McAllister, veteran stagehand at the Fox Theatre in Detroit, was coaching the company’s baseball team.

In May of 1951, Sport represented the Detroit Tigers at a ceremony that was held at Fenway Park in Boston commemorating the 50-year anniversary of the American League. At least one representative from every American League club in 1901 attended the historic event.

Lewis “Sport” McAllister died of a ruptured duodenal ulcer at the age of 87 at Wyandotte Hospital on July 17, 1962. He was the last surviving member of Detroit’s first American League team. His obituary in the Sporting News mentioned that he was a long time employee of the Detroit Opera House. Funeral services were held at Sacred Heart Church in Gross Ile, Michigan, and he was laid to rest at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Detroit. Lew’s wife Gertrude had passed away in 1943; his only survivors were his son Lewis Jr., two half-sisters, and one half-brother.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Wallace Hayden of the Bacon Memorial District Library in Wyandotte, Michigan, for his contributions to this biography.

Sources

Baltimore Sun 1896-1902-1912

Sporting News 1962

Sporting Life 1895 – 1915

Wyandotte News Herald 1962

Ancestry.com

Fort Worth Gazette 1895-1896

U.S. Census 1870-1880-1900-1910 –1920 –1930.

Full Name

Lewis William McAllister

Born

July 23, 1874 at Austin, MS (USA)

Died

July 17, 1962 at Wyandotte, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.