Ebbets Field, 1947

This article was written by Bob McGee

This article was published in 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers essays

In the spring of 1947, Ebbets Field was entering its 35th season, and in that year, more fans would pass through the fabled ball yard’s portals than in any other.

In the spring of 1947, Ebbets Field was entering its 35th season, and in that year, more fans would pass through the fabled ball yard’s portals than in any other.

The old ballpark was “the fun house of baseball,” as artist Andy Jurinko has said, with its cozy stands bringing fans near enough to the action to make matters up close and personal, whether for players, umpires, or the person sitting next to you.

It was close enough to hear the players’ chatter, close enough, if you were sitting in line with the first base bag, to see the whites of the first baseman’s eyes. It was close enough for those who were on the field to see and hear you. And to be seen and heard in Brooklyn, at Ebbets Field, was not to be forgotten.

It was a palette of color, from the ads on the outfield walls from the right field corner to the left, whether for Coca Cola, Botany Ties, Burma Shave, Gem Blades, or a host of others, save for a hitter’s blackened background in straightaway center.

There was the scoreboard that jutted out from the right-center field wall, along the right field wall that separated Bedford Avenue’s sidewalk from the field; it was the only wall in the ballpark that did not have a double decked stand behind it. The scoreboard, at each side, angled back to the wall, which was twenty feet high, topped by a twenty foot screen. The top ten feet of that wall were straight; the bottom ten feet were angled back towards the infield, wreaking unpredictable havoc with caroming fly balls.

The angled wall ran over from the right field corner to a double-door exit gate in deepest right-center field that President Roosevelt’s limousine had driven through merely two and a half years before. There was enough of a crack under those doors for children—hell, not just children, adults, too—to lie flat on their stomachs to watch a game. Occasionally, a street cop would come along and tap their heels with a billy club—time to move.

Atop the scoreboard was a Bulova clock. In May of 1946, the 30th to be exact, Bama Rowell of the Braves had stopped that clock in the second inning of a doubleheader’s nightcap, at precisely 4:25 in the afternoon. The ball stayed inside the clock for a double, the inspiration, of course, for the movie version of Bernard Malamud’s book, The Natural.

Below the clock, atop the scoreboard, there was a sign—not yet the Schaefer sign with the illuminating “h” and “e” for hit and error, which would come a year later; this sign invited you to “Shave Electrically.” And of course, there was the sign below the scoreboard, the Abe Stark sign, the sign that beckoned all “Hit Sign, Win Suit.” Ten years earlier, traded to the Dodgers in late career, the right-handed, right-field slice hitter, Woody English, had done so, and more than once.

But did you get a suit, Woody?

“The ball had to hit the sign on a fly, and the official scorer had to verify it,” English remembered. “By the end of the season I had hit the sign three times, so I went down to pick up my suits. A tailor was there—it wasn’t Abe Stark—and he went over to the counter and looked it up and sure enough, he saw that I had three coming. He said, ‘Right this way Woody’ and brought me over to this rack. He showed me these three pretty cheap lookin’ things…and I said, ‘Listen, just give me…one…good …suit.’

“He chuckled and said, ‘All right, Woody, c’mon back here.’ “He took me to the back, where the good suits were. And that’s what I got; one good suit.”

The walls were not padded. Pete Reiser had a nasty habit of running into them. It did not stop him. Another year would go by before that changed, and by that time, the prodigious promise of Pistol Pete would be largely spent, a product of the pounding.

It was 343 feet down the left field line; 297 down the right. Some 850 box seats had been added over the winter, bringing in the fences slightly; although the deepest recesses of right-center field was 407 feet, straightaway center field was only 386 feet, down fourteen feet from the year before.

Up in the bleachers, there were the leather lungs of Hilda Chester, who, warned by her doctors about the fragility of her heart, was given a school bell that she flagged relentlessly, while not abating the yelling at all. One time, when umpire Beans Reardon asked her why she yelled at the men in blue all the time, she replied, “Open your other eye, joik, you’ve got noive like a toothache.”

In the box seats, there was Jack Pierce, who would buy an extra seat for his helium tank; he’d spend time blowing up balloons, yelling “Coooooooo-kie!” serenading the man whose last name was Lavagetto.

In Section 8, there was Shorty Laurice and the Sym-Phony Band, an ever changing crew of musicians that included JoJo Delio, Lou Soriano, Patty George, Jerry Martin, Joe Zollo, and Zollo’s son Frank, the stalwarts. They routinely razzed the umpires with “Three Blind Mice.” No adequate adjustment was made when a fourth member was added to the crews.

When opposing hitters struck out, they were accompanied on their solemn walk to the dugout with “The Worms Crawl In, the Worms Crawl Out,” cymbals and chords blaring when the player took his seat on the bench. Catcher Walker Cooper once tried to outsmart them. He didn’t sit for several innings. When he finally did, they got him, drum and cymbals matching the posterior’s point of impact on the pine.

Public address announcer Tex Rickard would routinely intone that fans sitting along the rail in left field should please remove their clothes. Fans sitting along the third base line back towards that left field corner had good reason for removing their clothes from that special perch: for the last 15 or so feet up to the wall the foul line was painted right on the fence rail. If you were leaning against the rail, you were in fair territory.

Gladys Gooding, who for years played the organ at RKO and Loew’s Theaters before coming to Ebbets Field, was the answer to a trivia question about being the only person who ever played for the Dodgers, the Rangers and the Knicks.

Yet it’s the ethereal things that are hardest to pin down. The Ebbets Field smell has been alternately characterized as oily, inky, beery, a combination scent of hot dogs, mustard, peanuts, a smell of the grass intermingled, picked up even when walking through the Rotunda’s turnstiles down in the caverns, panoplied by the wafting aromas of the Bond Bread Bakery a few blocks away. Sweet.

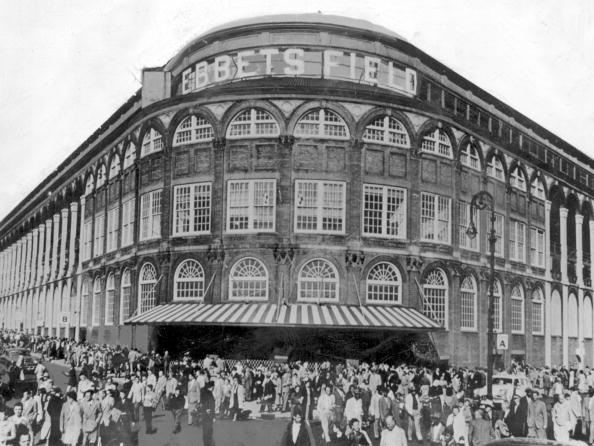

The most enduring image: the ballpark façade.

At the junction of Sullivan Place and McKeever Place, in spring, 1947, EBBETS FIELD, writ large in the setback, just below the ballpark’s crown, a flag rising precisely in the middle above, testified silently to the beauty of an immortal piece of Americana, and with it, the promise of what the American summer would bring.

And that façade itself, beauty incarnate: fourteen rows of small pane, Federal –style windows, separated by brick pilasters, running from the sidewalk or just above the main gate’s galvanized iron marquise above the entryway almost to the top of the wall, with gargoyles marking the spring line for the crowning, semi-circular windows above each row, where an ornamental circle of brick-belt coursing surrounded the windows, bas-relief medallions of baseballs populating the space in between each of them, a perfect tableau before entering the eighty-foot in diameter Rotunda, with ball and bat chandelier unobtrusively dangling from the 28-foot high elliptical ceiling. If the chandelier seemed high, it was only because the ballpark’s roof itself was only eighty feet off the ground.

Crowded, teeming, the Rotunda was all that symbolized what was wrong and right about the intimacy and design of Ebbets Field, inasmuch as the ticket sellers’ lines cascaded from interior ticket windows to the room’s center, while those holding tickets pushed their way through. But never mind! This was Ebbets Field, where the smell of the grass was already in your nostrils; this was the place where, on Opening Day 1947, a teenager standing and waiting to buy tickets in the morning at the advance sale window heard a commotion, and turned around to see a squad of policemen surrounding a black man who was a head taller than each of them.

This was the moment, the very moment, Jackie Robinson stepped across the threshold of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and prepared to take it to the world, which, as everyone from Brooklyn who ever crossed a bridge understood, is what life is all about.

BOB McGEE is author of “The Greatest Ballpark Ever: Ebbets Field and the Story of the Brooklyn Dodgers” (Rivergate, 2005), which won the 2005 Dave Moore Award. His sports articles have appeared in the “New York Times” and the “Oakland Tribune”; numerous other contributions have appeared elsewhere. He currently lives in Westchester County, north of New York City, but he’s always had a home in Brooklyn.