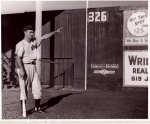

Neill Sheridan

Neill “Wild Horse” Sheridan was a classic “cup of coffee” major leaguer who saw brief duty in just two major league games, with the Red Sox in 1948.

Neill “Wild Horse” Sheridan was a classic “cup of coffee” major leaguer who saw brief duty in just two major league games, with the Red Sox in 1948.

Neill was born November 20, 1921 in Sacramento, CA. His father, Sol, worked for the California State Employment Service, and the family lived in Berkeley. His mother, Helen, went to her hometown of Sacramento for the birth of her son, but rejoined Sol, and young Neill was raised in the Bay Area. When Neil was ready for high school, Sol Sheridan was transferred back to the state capital and Neill went to Sacramento High School. He excelled in football at halfback and earned a scholarship to the University of San Francisco.

As a youngster, he’d always played baseball. “I’ve been playing since I was five years old. [Our family] were friends with Myril Hoag, who played with the Yankees. He got a ball for my brother Bill and me, from Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, and Hoag of course. I was about eight or ten years old. Hoag was from Sacramento. We were living in Berkeley at the time, but our families were friendly.” The Yankees became his favorite team.

Bill was two years younger, and both played on Berkeley playgrounds. Neill recalled, “We didn’t have any television or anything else. We had lots of fun and we played a lot of games.” Fun was one thing, but by the time it came to high school, Neil began to take part in school athletics. He went out for baseball at Sacramento High, but notes ironically that there was a very strong Legion team feeding players to the school at the time and he couldn’t make the team. He went out for track instead. And, as noted, he earned a football scholarship to USF. It wasn’t the most structured program. “At that time, USF didn’t have any schedule or anything like that. Mostly the younger part of my career was probably semipro. I could play and there were always a lot of teams around San Francisco in those days, so I played a little bit of that.”

He’d just turned 20 at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor. “I enlisted in the Marine Corps with the rest of our class. There were probably 12 or 13 of us.” One of whom was Windy McCall, a left-handed pitcher who also appeared briefly with the Red Sox. McCall was in the class behind Neill.

Sheridan got a medical discharge from the Marines because of asthma. The discharge happened even before boot camp, when Neill suffered an asthma attack. He returned to the recruiting office, but they wouldn’t take him because of his asthmatic condition. A visit to the draft board got him nowhere, either, so he went to work for the Kaiser shipyard in Richmond, California, working in the employment office, doing the same sort of work as his father did for the state.

The asthma didn’t hold him back from baseball, though. There was a shortage of players during the war years, and the head of one of the unions Sheridan dealt with was a friend of 11-year major league veteran Lefty O’Doul. This led to a tryout with the San Francisco Seals, and the Seals signed him, in time to get one at-bat in 1943. In 1944, he played most of the year at Chattanooga, though, batting .326 in 236 times at bat. He joined the Seals again later in the season, getting in 150 at-bats and hitting .293 over 42 games. Though ineligible for the Pacific Coast League finals, he hit .444 (12 for 27) against Oakland during the semi-final series.

Throughout, he played the outfield, though he’d begun semipro ball as an infielder. “I started out as a shortstop. I picked off a few people in the seats, and so I figured I better play in the outfield.”

The right-handed Sheridan was the first player to sign his 1945 contract with the Seals and signed onto marriage to Elizabeth Frank the same week. Ms. Frank was the daughter of Utah’s state treasurer. Sheridan played exclusively for the Seals from 1945 through the 1947 season, with averages of .290, .269, and .286, showing some extra power in 1947 (16 homers, matching the total of all his prior years) and 95 RBIs. It was while with the Seals he picked up the nickname “Wild Horse,” dubbed that by an older player named Ray Harrell who played for Seattle. “The way I ran, I guess my legs kind of went askew.”

Sheridan understands that the New York Giants sent as many as four or five players to the Seals to get an option on his contract. A June 1945 news story indicated that the Giants could exercise an option on him for $30,000, but they never pulled the trigger. Joe King, writing in March 1945, may have indicated part of the reason. “Sheridan is not a screwball, but he is on the temperamental side, according to coast information. He had to ride the bench several times last year as chastisement. He is fast, daring, colorful, and, at 22, is a wonderful prospect. The Giants will know better about him by August.”

Sheridan played in the PCL All-Star Game in both 1946 (a home run, a double, and five RBIs) and 1947 (two singles).

The day before the end of the 1947 Sox season, Boston dealt what The Sporting News termed “plenty of cabbage” and two players to be named later (Tommy Fine and Strick Shofner were named late in October) to San Francisco to obtain Sheridan in a September 25 transaction.

It wasn’t as though the Red Sox needed a left fielder, but Sheridan had somehow caught the eye of the Red Sox and they worked out a way to bring him into the Red Sox organization. A later issue of The Sporting News reported rumors that the signing might presage Dom DiMaggio’s departure from the Red Sox. Sheridan himself says, “I never did figure out why they signed me, because they had five established big league players to start with. We ended up in a playoff for the pennant.”

Sheridan went to spring training with the big league ball club. He opened the season with the big league club, renting an apartment in Boston for himself, his wife, and their daughter and infant son. About a week after they moved in, in early May, he was optioned back to the Coast League, to Seattle. With Ted Williams, DiMaggio, Stan Spence, Mele, and Wally Moses, “they figured out that they didn’t need six outfielders.” The Sporting News asked him how he’d gotten along with manager Joe McCarthy, and Sheridan said that McCarthy had only spoken three words to him all spring: “Nice going, kid” after he’d thrown out Dom DiMaggio taking a big turn at first base during an intrasquad game.

Sheridan had a very good year for Seattle, hitting .312, hitting 17 homers, and driving in 82.

In the final two weeks of the 1948 season, Sheridan was summoned to Boston. Sam Mele had hurt his right ankle sliding into third base. X-rays proved negative, but Mele was expected to be out for a week. The Red Sox at the time held just a one-game lead over the Yankees with 14 games to play. Sheridan’s debut came on September 19. It was in the second game of a doubleheader in Detroit. The Tigers won the first game, 4-3, in 12 innings. The score was 6-6 after six in the second game, and Wild Horse Sheridan was put in to run for Bobby Doerr when Doerr reached base but strained a leg muscle. No one knocked him in, though, and the Tigers scored twice in the bottom of the seventh to win a game called after eight innings on account of darkness.

One week later, he came in to pinch hit for Boo Ferriss in the top of the ninth, facing Tommy Byrne of the Yankees. New York had a 6-2 lead. “The first pitch Byrne threw me, I hit out of the ballpark foul. But in spring training the year before that, we played against the Yankees and I hit against Byrne and I got a couple of hits off him that day, so I guess McCarthy had an idea maybe I might get a hit off him if I was lucky. I was called out on strikes. Birdie Tebbetts was on second, and I asked him afterward, ‘Was that a strike, Birdie?’ And he said, ‘No.’ But that’s the way it goes.”

Sheridan stuck with the team, staying right through the playoff game against the Indians. He’d done well against Gene Bearden in the Coast League, but the Indians built up such a big lead early on that the game felt like a lost cause. The season over, Sheridan was sent back to Seattle in time for the PCL playoffs, but “Oakland wouldn’t let me play because I wasn’t there in time…they could have let me play if they’d given their permission, and consequently Seattle didn’t win the playoffs.”

Seattle was home for Sheridan in 1949, a little bit of a decline but still a respectable .259 with 14 homers and 67 RBIs. It was back to San Francisco for 1950, where he hit .288 with 12 homers and 54 RBIs in 319 at-bats. 1951 was a year he split between the Seals (.204) and Minneapolis (.306.) “When Willie Mays went to the Giants, I went to Minneapolis and took his place.”

The next year was an off-year, Sheridan hitting just .219 in 1952 in limited action for Toronto in the International League and .221 in the second half for Texas League San Antonio. He played for Oakland leading off 1953, but “Oakland ran out of money after about the first month of the season, and so I ended up in Sacramento and I played there for two years. That was about the end of my career.” But not before having at least one more very good night. “One night in Sacramento, one of the fellows was supposed to run against a horse. Well, he pulled a muscle or something so he couldn’t do it, so I ran against the horse and beat the horse. It ran between stakes, you know. It was fairly easy for me beating the horse, because the horse had a harder time going around the stanchions. The same night, I had a couple of home runs. I was pretty proud of myself that night. I pulled a hamstring the second year I was in Sacramento and they released me.”

That second home run, over the left-center field fence at Edmonds Field, was said to have traveled 613.8 feet, a legendary claim picked up by the Associated Press that made headlines around the globe.

That second home run, over the left-center field fence at Edmonds Field, was said to have traveled 613.8 feet, a legendary claim picked up by the Associated Press that made headlines around the globe.

He hit .293 in ’53, but only .153 in 22 PCL games for Sacramento/San Francisco in 1954. Sheridan moved to play for the Victoria (BC) Tyees in the Western International League. He played outfield until the Victoria franchise folded on August 2. Sheridan didn’t miss a beat; he flew to Vancouver, signed as a free agent, and played in the August 3 in a Caps uniform. For Victoria/Vancouver, Sheridan appeared in 95 games, driving in 76 runs and wound up his pro career batting .308 on the year. “Actually, I did pretty well in Vancouver and we won the championship [but] there wasn’t any prognosis that I was going to end up back in the big leagues. I went to work in the retail grocery business, and I retired there in 1982. Black’s Market, Orinda, California. We had a pretty good-sized supermarket and the fellow that I worked for put me in charge of the liquor department, and I worked doing that and the general run of things you do in a grocery store.”

He thinks back to his brief time in major league ball a bit wistfully: “I think if I’d have gone to a team that really needed somebody — the Philadelphia Phillies or Athletics, or the Washington Senators.…” Though a Yankees fan as a youngster, though, he remains a Red Sox fan today.

Sheridan’s son, who was a bit of an artist, died in the middle 1990s, but his wife and daughter remain, and he enjoys three granddaughters and five great-grandchildren. He enjoys hearing from the Red Sox alumni office and was very pleased when Boston finally won it all in 2004. “I think it was wonderful, especially for the fans that have been so loyal.”

Postscript

Neill Sheridan died at age 93 on October 15, 2015, in Antioch, California.

This biography originally appeared in the book “Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948,” edited by Bill Nowlin and published by Rounder Books in 2008.

Sources

Interview by Bill Nowlin done February 26, 2006

Unattributed news stories in Sheridan’s Hall of Fame player file.

King, Joe. “Sheridan, Coast Flycatcher, Adds Color to Giants” unidentified news clipping in Hall of Fame player file.

The Sporting News

Full Name

Neill Rawlins Sheridan

Born

November 20, 1921 at Sacramento, CA (USA)

Died

October 15, 2015 at Antioch, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.