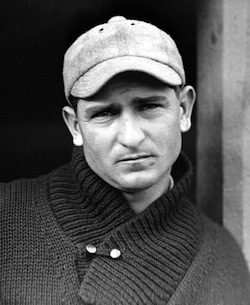

Rube Foster

Rube Foster was the star of the 1915 World Series, pitching two complete-game wins for the Boston Red Sox in a five-game series against the Philadelphia Phillies and going 4-for-8 at the plate. His ninth-inning single won Game Two.

Rube Foster was the star of the 1915 World Series, pitching two complete-game wins for the Boston Red Sox in a five-game series against the Philadelphia Phillies and going 4-for-8 at the plate. His ninth-inning single won Game Two.

Foster played pro ball for just one team in the big leagues, the Red Sox, with a career earned run average of 2.36 and a .637 winning percentage (58-33); in 842 1/3 innings of pitching, he allowed only six home runs. When the Sox traded him away, he refused to report and didn’t play in organized ball for the next five years.

In all he played 17 years in baseball, and had four wives (in succession) over the course of a long life. He was born in Indian Territory – in Lehigh, Oklahoma, on January 5, 1888.1 His father Jonathan Foster appears to have been a chair carver who had emigrated from England to the United States with his wife Mary and their four sons (Jonathan, Robert, John, and William.) George was the first child in the Foster family born in America. Another son, Alfred, and daughter, Katie, followed.

The 1900 census found the family living in Pittsburg, Kansas, where the three eldest sons worked as coal miners. Jonathan the son, age 25, was listed as head of family; their father may have died, because it appears that mother Mary married John Bowser, a German native, by the time of the 1910 census; several in the family had relocated to Marion, Ohio, including Jonathan, Robert, and George himself, who was now listed as a coal miner. He’d attended elementary school in Pittsburg for seven years but stopped his formal education at that time. He’d begun playing baseball in the meantime, beginning with Tulsa in 1908.

The Tulsa Oilers were in the Class D Oklahoma-Arkansas-Kansas League. Foster was 5-foot-7 and weighed 170. He was a right-hander. Sketchy records show him in 17 games for Tulsa, then as an outfielder with Bartlesville in 1909 and spending 1910 with three teams – Bartlesville, Arkansas, in April and semipro teams in Carson, Louisiana, and Steiger, Oklahoma. The season in Bartlesville ended early for Foster, because the team tried to make him into a second baseman and he demurred – and was fired. At some point, Foster also caught, and the Philadelphia Inquirer said he and a fellow coal miner (Tom Wilson, who played in just one game for the 1914 Washington Senators) worked as a “reversible battery, Foster pitching one day and Wilson catching, with Wilson pitching the next day and Foster catching.”2 Foster married Ruby Marie Wright in December.

In 1911, he topped his 1910 uniform changes by playing for four teams. He began with Savannah but was released in mid-April, then played for Muskogee until sold to the St. Louis Browns for $400 on July 2; he never played for the Browns, but was optioned to the Texas League’s Houston Buffaloes on July 20, where he was 7-13.

He enjoyed a breakout season in 1912, winning 24 games for Houston against 7 losses. The 24 wins tied him for most in the league and his winning percentage was tops; Houston finished first in the eight-team Class B league. Jim McAleer of Boston Red Sox drafted Foster, purchasing his contract from the Texas League, and then signed him for 1913, his contract arriving in Boston on January 2.

It’s hard to put full credence in the Washington Post article which suggested it might have been McAleer acting alone on the recommendation of Tris Speaker’s “old side partner” George Whiteman: “[T]he officials of the club are in utter ignorance whether he won twenty and lost none or lost twenty and won none: only that, it is understood, he is the pick of that league.”3

A story which appeared in the Washington Post in 1915 claimed that Foster had won the game clinching the Texas League pennant, with his hitting – a three-run come-from-behind home run with two outs in the bottom of the ninth against San Antonio. Ecstatic fans threw so much money at Foster that he gathered up $150, a large sum at the time.4

Rube Foster joined the Boston team at Hot Springs, Arkansas, for the 1913 exhibition season, and earned himself a spot on the reigning world championship team, though he was meant to be on the bench at first in favor of the returning champs. An early report from veteran sportswriter (and former ballplayer) Tim Murnane dubbed Foster “the compact youngster from the champion team of the Texas League” who “had perfect control” and “proved a puzzle for the Red Sox” in intrasquad work.5 He made the team on March 30, along with Dutch Leonard and Hal Janvrin, described by Murnane as with “real stuff …[and] a cool head.”6

He appeared in relief in the first game of the season, on April 10 at Fenway Park against the visiting Philadelphia Athletics. The defending world champions lost the first game of the season, 10-9, and each manager used three pitchers. Foster pitched a scoreless top of the ninth, walking one, striking out one, and allowing no hits.

He appeared in 19 games, starting eight of them, with four complete games, one of them a shutout. His first start came on April 18, in Philadelphia, an 8-5 win – but one in which Foster walked the first man on four pitches, then surrendered three hits, and was pulled before he even recorded an out. He didn’t start again until July 4, when he matched up against Eddie Plank, allowing just seven hits in a complete-game effort but walking four and losing 5-3. On July 10, he took a no-hitter through eight innings, and drove in two runs in the 6-2 win over the Browns, a two-hitter. Foster’s shutout came against Chicago on July 29 in the first game of a Fenway doubleheader, a 2-0 four-hit win. An injury to Foster’s knee curtailed his season; he wrenched it badly in the first inning of the August 2 game and finally left for his home in Bonanza, Arkansas, on September 1 – but before he departed, he was offered and signed his 1914 contract, the first one on the team to sign for the coming year.

Foster got off to a strong start in 1914, pitching the second game of the season, and struck out eight Senators while allowing just four singles and a walk, a 2-1 win played under cold and raw conditions. A nearly month-long homestand in May resulted in a pretty astonishing run before the hometown fans: Foster shut out the Yankees, 2-0, on May 7, then threw a 7-0 shutout of St. Louis on the 12th, a 2-0 shutout of the Tigers on the 18th, and a 1-0 shutout of Chicago on the 22nd. On May 26, he was going for his fifth consecutive shutout, but his teammates let him down. He was riding a streak of 42 consecutive scoreless innings when Cleveland came to bat in top of the fifth inning. He retired the first two batters, but then shortstop Everett Scott misplayed a ball. Two singles followed, scoring the first run. Harry Hooper dropped a fly in right field, and another run scored. Foster lost the game, 3-2. It was the sort of month, however, which can make a player’s reputation. A number of game stories comment on Foster fielding his position well.

Fielding did him in during another game, though, the August 2 loss against the Browns. Foster pitched all 12 innings of the 1-0 game, which St. Louis won on a squeeze play back to the mound which followed a drive that Tris Speaker had fumbled in center field. Even his last work of the season, when there was nothing to be gained in the standings, was superb, a two-hitter against Washington which should have been a shutout (the final was 8-4, but the four runs in Washington’s top of the ninth came on two errors, a walk, a hit-by-pitch, and the second of the two hits, a bases-clearing triple.)

Foster’s 1.70 ERA in 1914 was second on the team only to the 19-5 Dutch Leonard’s 0.96, which remains the best single-season earned run average of all time, in post-1900 baseball. Foster’s record was 14-8, with five shutouts (Leonard had seven). He would have pitched more, but again wrenched his knee while fielding a ball on June 25 and missed nearly a month before his next start on July 22. The Red Sox finished in second place, 8 ½ games behind the Athletics (who were swept in the World Series by the Miracle Braves). Foster bought himself a farm in Bokoshe, Oklahoma, during the offseason and worked at growing fruit.

Foster’s best year was 1915. His ERA climbed a bit to 2.11 (and both Joe Wood and Ernie Shore had better ones), but his 19-8 record tied him with Shore for best on the Red Sox, and his work in the World Series was beyond compare.

He’d predicted the pennant for the Red Sox back in February, when he’d written team secretary Eddie Riley, “Don’t fail to bring along your checkbook” to spring training.7 Sometimes the headlines were heady: “Walter Johnson Met His Master,” proclaimed one in the Boston Globe after Foster’s 2-0 shutout of the Senators on May 4.

Once again, he threw five shutouts, three of them between August 9 and September 1, and two of them against the Browns in a six-game stretch (August 9 and 12, with Foster doubling twice and scoring twice in the game on the 12th.)

The pennant was indeed Boston’s, and manager Bill Carrigan asked Foster to pitch Game Two, after the Phillies’ Grover Cleveland Alexander took the first game against Shore, 3-1. With President Woodrow Wilson watching the game at Baker Bowl, Foster threw a three-hitter, winning 2-1. Not only did he pitch superbly, but he was 3-for-4 at the plate–making as many hits himself as he allowed–and driving in the tie-breaker in the top of the ninth, while running and fielding superbly as well. The New York Times even allowed that Foster’s work “eclipses the President.”8

On the day of Game Five, Boston was up three games to one, and Foster was given the ball again. He didn’t have the easiest time, with Philadelphia’s Fred Luderus doubling in the first two runs of the game in the bottom of the first inning, and then hitting a solo homer in the fourth to re-establish the lead. A fourth run scored in the fourth on an error by right fielder Harry Hooper, but Hooper had earlier tied the game in the third with his own home run, seen Duffy Lewis hit a two-run homer in the top of the eighth to tie the game again, and then homered again in the top of the ninth to give the Red Sox a 5-4 edge. Foster struck out the first batter in the bottom of the ninth and then induced two easy grounders to close out the game, and go 2-0 in the World Series with a 2.00 ERA. He was 4-for-8 at the plate.

In an unusual matchup, Foster pitched against Walter Johnson during an exhibition game in Webb City, Missouri, on October 24, beating the Big Train, 3-0 – though the game had been scoreless for the first eight innings. Johnson pitched for Webb City while Foster pitched for Pittsburg, Kansas.

Foster was the subject in January of an unusually detailed profile by Tim Murnane, who had stopped off at Fort Smith, Arkansas, while traveling by train across country in November 1915 and made the 28-mile side trip to Foster’s farm in Bokoshe, a town of about 400. Foster, his wife, George Jr., and their daughter welcomed Murnane at the train station. Foster’s land had a good deal of oak on it, and he’d cleared and planted 14 acres of an apple orchard. He was building a new home on a hill overlooking the town “sleeping in the valley below.”9 He also had mulberry and cherry trees. His 300 acres had been purchased for $6 an acre. He had 30-40 acres of cotton planted as well. Much of Foster’s knowledge of farming had come, he explained, by taking courses in farming, building, and business; the cherry trees, he’d learned, attracted birds and kept them sufficiently satisfied to leave the other crops alone. Both Foster and his wife told Murnane he only planned to pitch a few more years, make what money he could, and then settle down for good and enjoy the simple life with family and farm.

The Red Sox had lost the services of Tris Speaker, but had another excellent season, winning the pennant again. In 1916, “little George Foster, the farmer boy from Oklahoma” (as the New York Times described him) threw the first no-hitter in a Red Sox game at Fenway Park, on June 21, 1916, beating Bob Shawkey and the Yankees, 2-0.10 Foster walked three, one apiece in the sixth, seventh, and eighth. There were 11 fly balls to the outfield but nary a base hit. The win earned Foster a $100 bonus from Red Sox President Joseph Lannin. The next day’s Globe added, “Little George looked mighty big yesterday.”

He was 14-7 (3.06) on the 1916 season, with “only” three shutouts. Babe Ruth led the team with a 23-12 record and an ERA of 1.75. The Red Sox returned to the World Series, this time facing Brooklyn. Ruth, Shore, Carl Mays, and Leonard were the main men on the mound, as they had been during the regular season. Foster had missed time near the end of the season due to a lame arm, from which he had suffered about half of the year, but it had been thought he might start Game Two. As it happened, he appeared in just one game, Game Three, working in relief of Mays. It was the one game the Red Sox lost; Foster threw the last three frames, allowing three hits but no runs.

Four days after the Series was won, the players divided up the receipts, and Foster announced his retirement. He was 28 years old, but wanting to settle in with his family and work his farm.

His retirement lasted three months. Asking only for a modest $500 increase in salary, he let the Red Sox know in January that he was in tip-top shape after the time off from pitching and would like to return for one more season. He’d be set to earn $6,000.11

New owner Harry Frazee came to terms with Foster, but Bill Carrigan’s retirement was final. Foster pitched one game in relief on April 23, and was hammered for three runs in the ninth inning causing a 9-6 loss to New York. He suffered from a sore arm for much of the early part of the season, and new manager Jack Barry didn’t use him again until June 18, and even then only because Dutch Leonard had hurt his foot in morning practice. He only lasted five innings and was pulled in favor of Herb Pennock, who won the game only because the Red Sox scored four runs in the ninth.

Foster started 15 more games, through the rest of the season. It was an uneven season, with him sometimes pitching well and sometimes getting hit hard. Nine of his 16 starts were complete games. His best effort was a superb one-hitter on August 6 against the Indians. He walked two batters and then surrendered a double, giving the Indians a 2-0 lead. Boston never scored off Ed Klepfer and Jim Bagby, and Cleveland never got another hit. Foster lost the hard luck one-hitter, 2-0. On September 7, he shut out the Athletics, 5-0, his only shutout of the season. He finished up with an 8-7 record and a 2.53 ERA. He announced his retirement in December. Half of his teammates were already in military service or performing defense work.

The Red Sox hoped he’d return in 1918, but in April finally traded his contract to the Cincinnati Reds for Dave Shean. He demanded $6,000 from the Reds, but they weren’t inclined to even consider paying that much. Foster refused to report, and the Red Sox were only able to keep Shean by sending cash to Cincinnati in place of the player the Reds had hoped to acquire.

Though he hadn’t pitched since 1917, for the next six years he remained on the books of one team or another according to the detailed records of baseball, listed on teams located in Fort Smith and Springfield, Missouri, and he was even on the Red Sox books for part of 1920, given that the trade to Cincinnati had never been consummated. In late July 1922, he was named manager of the Springfield (Missouri) Midgets, of the Western Association.12 He’d been playing second base with the Henryetta (Oklahoma) Hens, and batting .331 in 77 games, before being traded to Springfield.13 He resigned in November.

In 1923, Foster decided to give pitching another try, and he was signed by the Vernon Tigers of the Pacific Coast League. Playing under manager Bill Essick, the 1923 team performed poorly (they’d finished second just the year before), ending up in last place. Foster was 3-9, even worse than the team’s record, and had a 4.08 ERA. Worse, come late August, he refused to travel with the team to go to Salt Lake City and was released on August 25. Foster said that he wife was seriously ill, but Essick “said he did not believe Mrs. Foster’s illness was serious enough to warrant Foster’s absence from the club.”14 In fact, she was quite ill and died on November 15, 1924, leaving the couple’s three children in Foster’s care. The Oaks had donated all the proceeds of their September 18 game to him, and his teammates had gone into the stand and collected $1,122 additional money.15

The Oakland Oaks finished 1923 just ahead of Vernon and were desperate for pitching in 1924, so they signed Foster in mid-January. He improved to a 3.59 ERA but his won-lost record was again worse than his team’s, 12-18. Foster pitched again for the Oaks in 1925, but was 4.95 and 9-15.

The Oaks released him in early 1926 but he caught on with the Mobile Bears, managed by old Red Sox teammate Duffy Lewis. He appeared in 26 games, with a reported record of 4-8 and a 6.59 ERA. On July 31, he joined the Dallas Steers.

Near the end of 1926, he played for the Globe, Arizona Bears (Arizona State League.) He returned to pitching in 1927, and worked almost the entire 1927 for the Chino ballclub in the outlaw Copper League. On July 15, he returned to Globe, named player/manager for the Globe Bears.16

On March 9, 1928 he signed on a player/manager for the Tucson Cowboys of the brand-new Class-D Arizona State League. It was a four-team circuit and only played a 68-game schedule. Tucson finished tied for last place, 30-38.

He could look back on a major-league career, entirely for the Red Sox, with two World Championships and two World Series wins, his 58-33 record and lifetime 2.36 earned run average. His career batting average in the majors was .215 with one home run (in 1915) and 19 runs batted in. He had a .970 fielding percentage, but made an impression on Babe Ruth with his defense. Some years later, Ruth wrote, “The best fielding pitcher I ever saw, I think, was George Foster of the old Red Sox. George was sure death on any ball hit to his territory.”17

Foster kept his hand in the game a little, managing for Class D Tucson in 1928 and 1929, for nearby Fort Smith in 1930, and in North Dakota for the Jamestown Jimmies for the first half of the 1936 season. He had meanwhile been pursuing other lines of work. In 1920, in between leaving the Red Sox and returning to the Coast League, he’s found as the proprietor of a furniture store in Fort Smith and he played the last half of 1920 with the Fort Smith team.18 The same article said he hoped to play again for the Boston Red Sox in 1921. Researcher Chris Woodman reports, “He actually signed a contract with the Red Sox, but, on the day he was to leave for spring training, was stricken with appendicitis.”19 It didn’t come about. He did take up other work in 1921; he seems to have performed unspecified duties for the United States Treasury Department, specifically the United States Secret Service.

In June 1925, the widowed Foster married Demarious Quick (the spelling of her surname is visible on the grave marker she shared with her husband). There were two later wives (whose names we cannot make out) as well, according to the player questionnaire he completed for the Hall of Fame. The nickname “Rube,” he said, had been given him by Boston pitcher Charley Hall. There may be hyperbole here, but Foster claimed to have invented the screwball in 1911 in Houston “and using this pitched 62 straight shutouts without being scored on, one of these being a double hitter [sic].”20

Foster died in Bokoshe on March 1, 1976, at age 88. He is buried in the Milton Cemetery at Bokoshe.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Foster’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Chris Woodman, who contributed valuable information improving an earlier version of this biography.

Notes

1 Oklahoma did not become a state until November 1907.

2 Undated 1915 clipping located in Foster’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

3 Washington Post, January 2, 1913.

4 Washington Post, October 12, 1915. See also the Post of October 31, 1915.

5 Boston Globe, March 8, 1913.

6 Boston Globe, March 31, 1913.

7 Boston Globe, February 19, 1915.

8 New York Times, October 10, 1915.

9 The lengthy piece ran in the January 16, 1916 Boston Globe.

10 New York Times, June 22, 1916.

11 Boston Globe, January 28, 1917.

12 Washington Evening Star, July 26, 1922: 22, and Boston Globe, January 17, 1924.

13 Miami Herald, August 19, 1922: 7.

14 Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 26, 1923: 42.

15 Oakland Tribune, September 19, 1924.

16 Numerous articles in the Arizona Republic (e.g., May 10, 1927) and El Paso Herald (e.g. May 23 and August 14, 1927).

17 San Diego Evening Tribune, January 31, 1929: 20.

18 Miami (Oklahoma) District Daily News, February 22, 1921: 2.

19 E-mail from Chris Woodman, March 20, 2016, citing the Springfield Leader, June 30, 1921.

20 Foster player questionnaire at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Full Name

George Foster

Born

January 5, 1888 at Lehigh, OK (USA)

Died

March 1, 1976 at Bokoshe, OK (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.