April 14, 1925: First radio broadcast from Braves Field

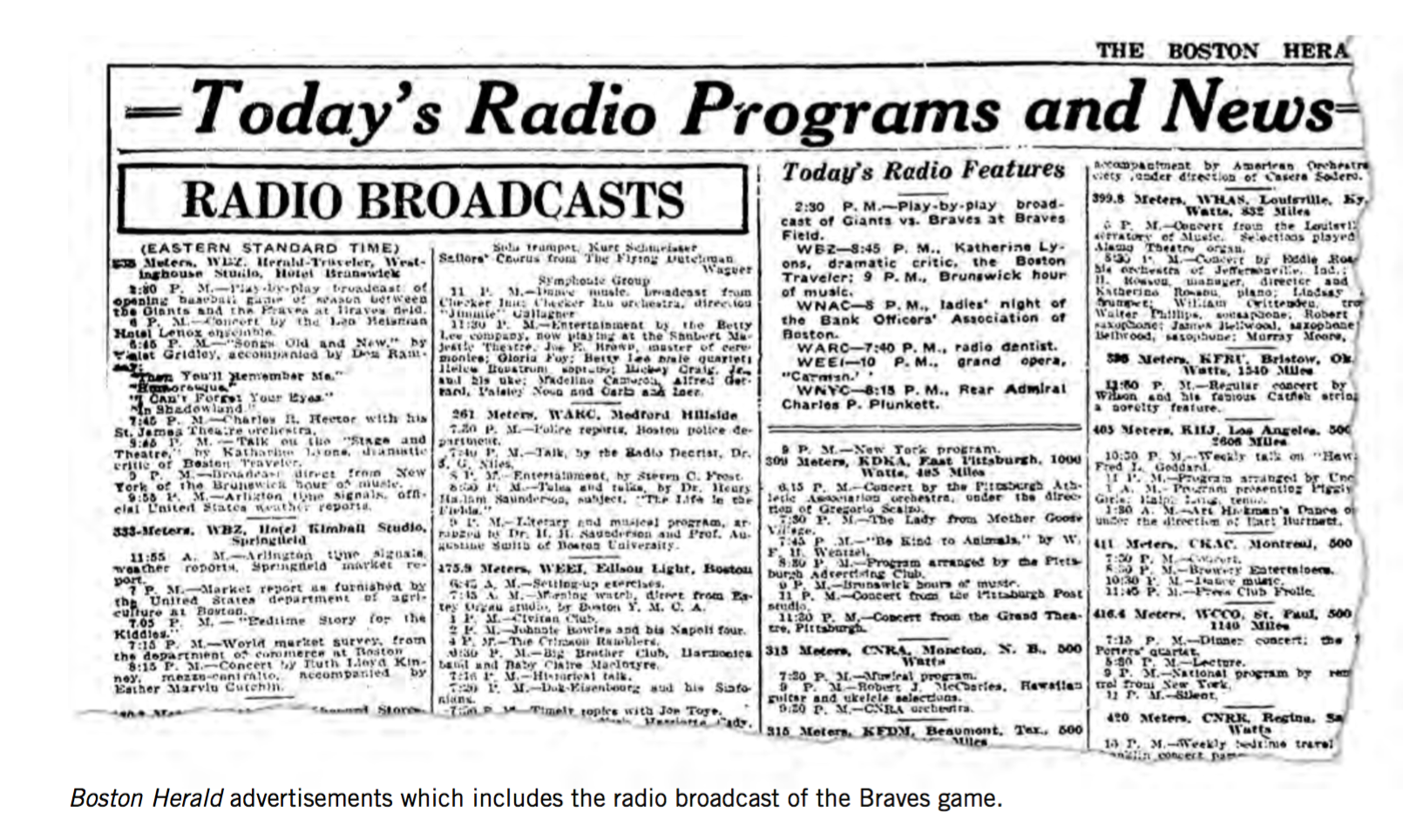

The first radio broadcast at Braves Field took place on April 14, 1925. The WBZ broadcast was believed to be the “First Time Radio Fans Have Been Given Such a Treat, Other Than During the World’s Series,” wrote the Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican.1 Both the pregame ceremony and the game would be broadcast in their entirety, “courtesy of the Western Union Company and the Crosscup-Pishon post of the American Legion, Members of the 40 American Legion posts in Boston, and veterans from the government hospitals near Boston will be guests at the game.”2

The first radio broadcast at Braves Field took place on April 14, 1925. The WBZ broadcast was believed to be the “First Time Radio Fans Have Been Given Such a Treat, Other Than During the World’s Series,” wrote the Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican.1 Both the pregame ceremony and the game would be broadcast in their entirety, “courtesy of the Western Union Company and the Crosscup-Pishon post of the American Legion, Members of the 40 American Legion posts in Boston, and veterans from the government hospitals near Boston will be guests at the game.”2

“A capable announcer will be before the WBZ microphone and fans who are unable to attend this game in person should enjoy the broadcast,” the Republican advised its readers.3 If anything, “capable” turned out to be an understatement: Describing the action was Joe E. Brown, a famed actor, comedian, and baseball fan.4

This was Opening Day with all its glamour and familiar pageantry. The “first pitch” was thrown by Massachusetts Governor Alvan T. Fuller, with Boston Mayor James Michael Curley catching, National League President John Heydler at bat, and Massachusetts Lieutenant Governor Frank Allen umpiring. Much was made of the mayor muffing the pitch. Soldiers, sailors, and members of the Legion marched, and 150 veterans of the West Roxbury (Boston) Hospital glee club sang selections during the game. A stiff wind blew through the field on that chilly April day in Boston, and many topcoats and shawls were seen in the crowd. The Boston Herald noted, “Some far seeing fans in the boxes brought along their automobile robes, and after the sun hid behind those cloud banks and the east wind began sweeping in off the river late in the game, the extra protection came in handy.”5

Player-manager Dave Bancroft of the Braves and players Hank Gowdy and Hugh Jennings of the Giants took advantage of the “temporary sending station that WBZ had installed in a box behind home plate.”6 Bancroft asked Jennings if the Giants were going to win the pennant, to which Jennings replied, “Why, of course.”7 Not exactly an engaging interview, but definitely an historic one. The Boston Globe even included a picture of the interview with the caption, “Telling it to Radio Audience Before Teams Begin Battle.”8

Jesse Barnes took the hill for the Braves, and was opposed by his former Braves teammate, Art Nehf of the Giants. The Giants were defending National League champions for the fourth consecutive season.

With two out in the first inning, the Giants’ Ross Youngs reached second on a throwing error by Bancroft. George “High Pockets” Kelly walked and scored with Youngs on a triple lined off the center-field fence by Bill Terry that James C. O’Leary of the Globe called “undoubtedly the longest hit ever made in a game at Braves Field.”9 Burton Whitman of the Herald remarked, “Had the barrier in centre been made of middle aged pine, that smash would have penetrated said fence like a bullet boring through cheese.”10 The Giants led, 2-0.

The Braves came back with four runs in the third inning. Red Lucas led off with a walk, and Frank Gibson singled. Lucas was thrown out at third on an attempted sacrifice bunt by Barnes. A fly ball by Bernie Neis to right-center fell between Youngs and Hack Wilson, allowing Gibson to score. A single by Bancroft scoring Barnes was followed by a single by William Marriott that scored Neis. Bancroft scored when Terry dropped a throw to first base from Frankie Frisch. The Braves led 4-2. They added an insurance run in the seventh inning on a sacrifice fly by Bancroft.

Nehf had allowed only one single since the third inning, but in the eighth inning Heinie Groh led off with a double and scored on a groundout, making the score 5-3 Braves. In the Giants’ ninth inning, Wilson drew a walk and scored on a triple by Emil “Irish” Meusel, who could have scored on a better set of wheels. Frank Walker was sent in to run for Meusel, representing the tying run with only one out. Jack Bentley pinch-hit for the pitcher and hit a wicked grounder to first base. Dick Burrus raced in and cut down Walker with a sweeping tag by Gibson at the plate. Groh next hit a foul popup into the wind. Third baseman Marriott struggled with it but made a one-handed catch to preserve the 5-4 win for the Braves, their shivering fans in the stands, and all of the first-time listeners on Boston radio. The Braves “convinced the 10,000 fans who turned out that they are a fighting bunch,” wrote O’Leary, despite the fact that “the weather was more suitable for football than baseball.”11

Not everyone was thrilled about baseball broadcasting, and one writer even saw doom for the future. In his column “The Once Over,” The Globe’s H.I. Phillips spoke of news that “Radio Movies” would soon become a reality through the invention of Charles Francis Jenkins, who would one day become one of the inventors of television. Phillips dreaded the day when “people will soon be able to sit at home and see the World Series, Olympic Games, Missouri cyclones, fires, floods, riots and murder trials without putting on their shoes. Folks can see everything there is to see and hear everything there is to hear merely by twisting a knob. Thus is the prospect of the dishes getting washed in the Great American home rendered more remote than ever. … All that remains to be perfected is a device to broadcast fresh roasted peanuts, ice cold cones and ‘hot dogs’ to every home.”12

A version of this article appeared in “Braves Field: Memorable Moments at Boston’s Lost Diamond” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and Bob Brady. To read more articles from this book, click here.

Acknowledgment

SABR member Donna L. Halper provided research assistance identifying Joe E. Brown as the announcer for the radio broadcast, allowing this article to be updated in February 2022.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the text, the author used retrosheet.org and baseball-reference.com for game information.

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/BSN/BSN192504140.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1925/B04140BSN1925.htm

Photo credit

Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection

Notes

1 “WBZ Will Put Major League Game On Air Today, New Departure,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, April 14, 1925, 1.

2 “WBZ Will Put Major League Game On Air Today, New Departure.”

3 “WBZ Will Put Major League Game On Air Today, New Departure.”

4 “Through the Static,” New Britain (Connecticut) Herald, April 15, 1925: 9. In July of 1925, WNAC was given permission to broadcast five games from Braves Field, with Benjamin H. Alexander and Charles Donelan doing the announcing“Baseball Broadcasts,” Boston Globe, July 7, 1925, 17; Curt Smith, Mercy!: A Celebration of Fenway Park’s Centennial Told Through Red Sox Radio and TV (Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books, 2012), 24.

5 “Fuller and Curley Were Battery Mates for a Day; His Honor Muffed Again,” Boston Herald, April 15, 1925, 20.

6 “Fuller and Curley Were Battery Mates for a Day.”

7 “Fuller and Curley Were Battery Mates for a Day.”

8 Boston Globe, April 15, 1925, 13.

9 Boston Globe.

10 Burton Whitman, “Braves Top Giants, 5-4, In Thrilling Opening Of Big League Season,” Boston Herald, April 15, 1925, 1.

11 James C. O’Leary, “Revamped Braves Start By Beating Giants, 5-4,” Boston Globe, April 15, 1925, 13. Retrosheet.org lists the attendance as 15,000, not the 10,000 cited by O’Leary.

12 H.I. Phillips, “The Once Over: Home, Static Disturbance, There UIs No Place Like Home,” Boston Globe, April 14, 1925, 16.

Additional Stats

Boston Braves 5

New York Giants 4

Braves Field

Boston, MA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.