August 13, 1916: Braggo Roth walks off with inside-the-park home run

On July 23, 1916, the St. Louis Browns defeated the Cleveland Indians by a score of 5-2. The Browns scored three runs in the top of the 10th inning to boost their record to 38-49. The victory in itself was rather ordinary, but the win began an incredible streak for the Browns, who went 23-2 in the next 25 games. It was quite a ride for the Browns, who completed four sweeps within that span. They swept Philadelphia in five games, New York in six, Washington in five, and Cleveland in three.

On July 23, 1916, the St. Louis Browns defeated the Cleveland Indians by a score of 5-2. The Browns scored three runs in the top of the 10th inning to boost their record to 38-49. The victory in itself was rather ordinary, but the win began an incredible streak for the Browns, who went 23-2 in the next 25 games. It was quite a ride for the Browns, who completed four sweeps within that span. They swept Philadelphia in five games, New York in six, Washington in five, and Cleveland in three.

The Browns’ record stood at 60-51-3 as they moved from seventh to fourth place in the American League. The third game against Cleveland was won by Eddie Plank, who was winding down his Hall of Fame career. Plank, who would turn 41 on the last day of August, blanked the Tribe, 11-0. He scattered two hits to raise his record to 12-10.

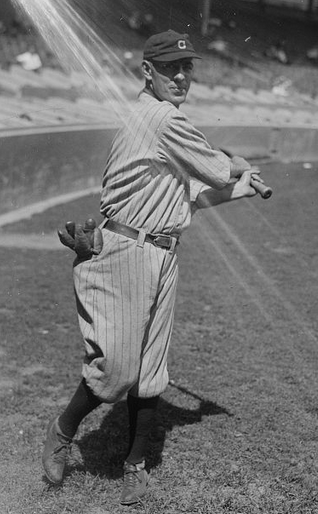

Despite the lopsided score, the game did hold some excitement, especially for those rooters sitting in the right-field stands at Sportsman’s Park. As often happens when the fate of the ball game is decided early (the Browns scored nine runs in the first inning), the paying throng must find something else to hold their attention. That something else turned out to be Cleveland right fielder Bobby “Braggo” Roth. The cleanup hitter in the Indians lineup had thus far taken the collar in the series, going 0-for-10. The Browns faithful began verbally abusing Roth. Braggo, who could be charitably characterized as temperamental, chose to shoot back at the fans instead of ignoring their barbs. The more he paid attention to them, the more the insults flew. After a while, pop bottles began to rain down on the right fielder.

Umpire Tommy Connolly pulled Roth from the game in the eighth inning, and he was replaced by Fritz Coumbe. The circumstances of Roth’s removal are a bit murky. The Cleveland Plain Dealer indicated that he was removed for his own safety. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch wrote that Roth heaved a pop bottle into the stands in retaliation, and thus was ejected from the game. Other sources assert that Roth was ejected for using vulgar language toward the patrons. The Post-Dispatch had it right.

The teams traveled to Cleveland for one game on August 13, 1916. St. Louis skipper Fielder Jones and the rest of the Browns were surprised to see Roth in uniform. Earlier in the year, Detroit’s Ty Cobb had been suspended for three games when he threw his bat into the stands at Comiskey Park. The bat landed just beyond the first-base dugout. Luckily, it had begun to drizzle and that area had been vacated. Nonetheless, Cobb had been fined $25 and given a three-game suspension by American League President Ban Johnson. Surely if Roth threw a bottle into a crowded area of the stands, there would be punishment to be meted out. But the Post-Dispatch wrote that Connolly did not report the incident. So here was Roth, penciled in as the cleanup hitter and right fielder.

Just before the 1916 season began, the Indians made one of their greatest trades ever. Tris Speaker, a star center fielder for the Boston Red Sox, was in a contract stalemate with the Boston front office. He was a mainstay on their 1912 and 1915 World Series winners. He had batted over .300 (well over) the last seven seasons. He was a superior center fielder with great speed. The Indians sent pitcher Sad Sam Jones, infielder Fred Thomas, and an almost unheard of $55,000 to the Red Sox. “I suppose I must play in Cleveland,” said Speaker. “If you want to continue in the big show you must go where the owners send you. I hate to leave Boston, for I like the people here. I have never played big league ball for any other team than the Red Sox.”1

A player of Speaker’s ability on the diamond, combined with his leadership off it, gave instant credibility to the Indians. Their lineup had to be looked at with a bit more respect. He was not a mere replacement for Joe Jackson, whom Cleveland had traded to Chicago the year before. Speaker was an upgrade. For comparison’s sake, Cleveland shelled out almost double the money for Speaker that they had received from the White Sox for Jackson. As part of the deal with the Sox, Cleveland obtained outfielder Braggo Roth. But the native of the “Windy City” played sparingly for the hometown team.

The attendance of 18,000 at Dunn Field was boosted by a few hundred fans who made the trek from Akron, Barberton, and Amherst to cheer for their favorite sons: Browns first baseman George Sisler (Akron, Barberton) and Browns outfielder Burt Shotton (Amherst). Dunn Field, which was located at E. 66 and Lexington Avenue, had been named League Park. But the name was changed after new Indians owner “Sunny” Jim Dunn purchased the club in 1916. It reverted back to League Park in 1928.

The starters for the game on August 13 were Cleveland’s Otis Lambeth and the Browns’ Carl Weilman. But the St. Louis hurler wasnot in the game long enough to break a sweat. A walk to Jack Graney led off the bottom of the first inning. Ray Chapman sacrificed him to second base. Speaker was intentionally walked and Roth singled through the box to load the bases. Weilman was removed in favor of Dave Davenport. Bill Wambsganss grounded out to the shortstop to score Graney for the 1-0 Cleveland lead.

Fielder Jones demonstrated his respect, or his fear, of Speaker. Spoke was intentionally walked three times in the game to bring Roth to the plate. In the third inning Graney bunted safely and went to second base when Speaker was given the free pass. Roth singled again and Graney scored to give the Tribe a 2-1 lead. In the seventh inning Graney walked, Chapman sacrificed, and Speaker was passed again. To prove it was no fluke, Roth collected his third hit and second RBI by singling home Graney. Cleveland led 3-2.

The Browns tied the score in the top of the ninth inning. Davenport had done yeoman’s work since entering the game in relief in the first inning. But in the ninth he was lifted for pinch-hitter William Rumler, who walked. Jack Tobin came in as a pinch-runner. After Lambeth pitched two wide ones to Shotton, Jim Bagby came in to relieve him. The maneuver did not pay dividends as Shotton singled. Ward Miller sacrificed the runners to second and third and Sisler was intentionally passed, loading the bases. Del Pratt grounded to second base to push across the tying run.

St. Louis’s Earl Hamilton came in to pitch the ninth. Trying a different tack, Hamilton pitched to Speaker, who popped out to second baseman Pratt. Up came Roth, who drove a fastball from Hamilton to center field. Armando Marsans, a speedy player, took one look from his center-field position and retreated to catch up to the hard-hit sphere. Henry P. Edwards of the Cleveland Plain Dealer wrote: “The Cuban is fleet of foot, but even his speed would not allow him to catch up with the ball, which traveled like a bullet and never stopped until it bounded against the scoreboard. Roth was well past second when the Cuban picked it up. He never hesitated in rounding third and dashed home standing up as Marsans’ throw to one of his mates who rushed into the field to act as a relay man went astray.”2

The Indians rushed out to celebrate the victory and Roth’s heroics. The fans cheered until their voices turned hoarse at the way the sudden and unsuspecting victory had been delivered. “I intended to pitch Hamilton to only one batter in the ninth,” said Jones. “I wanted him to dispose of Speaker and then I meant to use Bob Groom. Ham got rid of Speaker so easily that I made the mistake of weakening on my first guess. I suffered Hamilton to tarry. He got into the hole on Roth, two balls and no strikes, and then tried to pump a fast one past him. Roth broke up the game. It might have been different had I switched to Groom.”3

As it turns out, Roth had indeed thrown a pop bottle into the right-field stands at Sportsman’s Park on August 12. Even though no one was injured, Ban Johnson handed down a four-game suspension to Roth. He was replaced in right field by Elmer Smith.

By season’s end, neither team figured in the pennant race. Both teams stumbled in September to take themselves out of contention for the flag. St, Louis posted a 9-17 mark while Cleveland was 9-16.

Roth had a tumultuous relationship with Indians manager Lee Fohl. Constant feuding and a couple of suspensions handed down by Fohl did not ease the tension between the two. In 1919 Roth was dealt to the Philadelphia Athletics. In another great trade by Cleveland, outfielder Charlie Jamieson and third baseman Larry Gardner came to the Wigwam. Both were cornerstones on the Indians’ 1920 world championship team.

Notes

1 Scott H. Longert, The Best They Could Be (Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books, 2013), 27-28.

2 Henry P. Edwards, ”Roth Smashes Out Homer in Ninth and Wins Game,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 14, 1916: 9.

3 W.J. O’Connor, “Roth’s Slashing Home Run Crushes Brownies, Who Had Tied the Count in Ninth,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 14, 1916: 12.

Additional Stats

Cleveland Indians 4

St. Louis Browns 3

Dunn Field

Cleveland, OH

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.