Circa 1840: The legendary Doubleday Game

By 1905, pitcher-turned sporting goods entrepreneur Albert Spalding was sorely fed up with his friend Henry Chadwick’s notions concerning baseball’s origins. The British-born sports journalist Chadwick, who had been studying and writing about the game since the late 1850s, pushed Spalding’s tolerance to the limit by asserting, in Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide for 1903, that our National Pastime had developed from an English game called rounders. Spalding, believing baseball a thoroughly American invention, but lacking proof, decided to remedy the situation by convening a special commission that would examine all evidence and render a definitive answer.

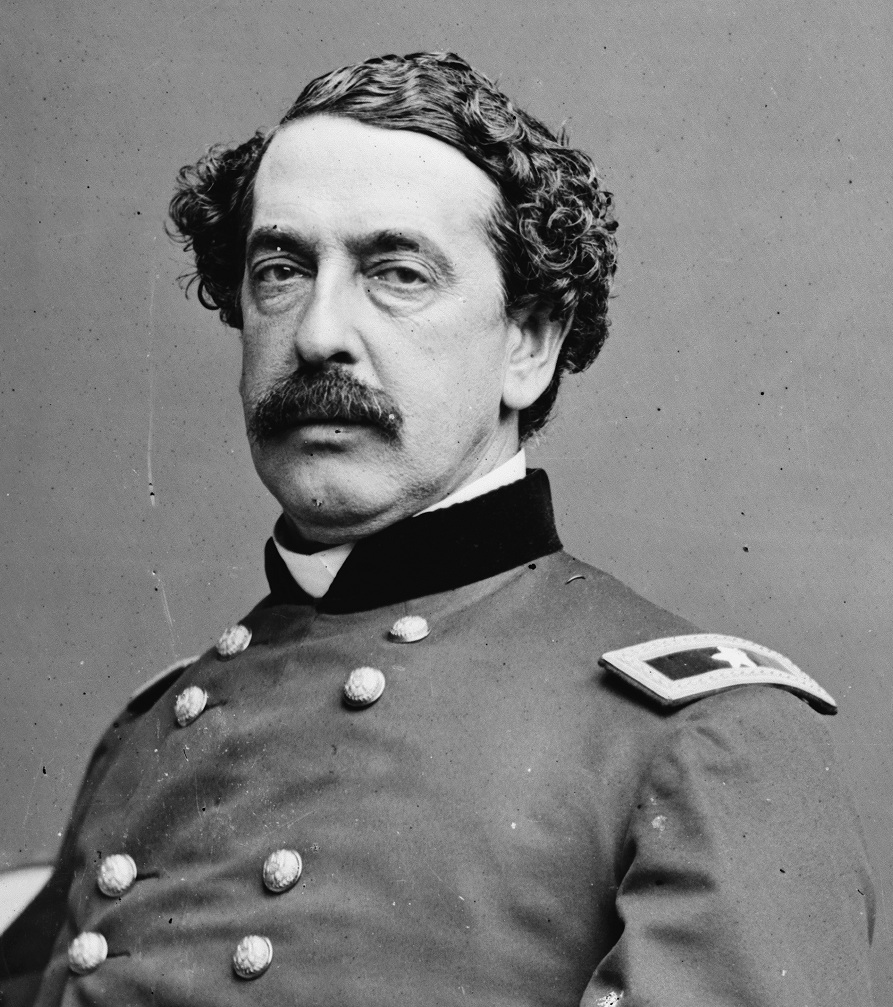

Two years of haphazard information-gathering produced a ragged body of data unlikely to ratify either man’s theory. But amidst it all, Spalding found something he liked. A 71-year-old Denver mining engineer named Abner Graves wrote in 1905 two letters (one to the editor of the Akron, Ohio Beacon-Journal and the other to Spalding) recounting how, in his childhood home of Cooperstown, New York, a boy named Abner Doubleday surprised his playfellows one fine day with a concept for a game called “base ball.”[fn]The two letters, dated April 3 and November 17, 1905, are printed in David Block, Baseball Before We Knew It: A Search for the Roots of the Game (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2005), pp. 252-256.[/fn] Spalding must have been overjoyed when he realized that not only had he found an eyewitness account affirming baseball’s American origin, but that its purported inventor grew up to be a military hero in the Civil War![fn]For more on connections between Spalding and Doubleday, see Philip Block, “Abner and Albert, The Missing Link,” Chapter 3 (pp. 32-49) in David Block, Baseball Before We Knew It.[/fn] Lacking anything more substantive or suitable to their inquiry, Spalding and the commission ran with it.

Two years of haphazard information-gathering produced a ragged body of data unlikely to ratify either man’s theory. But amidst it all, Spalding found something he liked. A 71-year-old Denver mining engineer named Abner Graves wrote in 1905 two letters (one to the editor of the Akron, Ohio Beacon-Journal and the other to Spalding) recounting how, in his childhood home of Cooperstown, New York, a boy named Abner Doubleday surprised his playfellows one fine day with a concept for a game called “base ball.”[fn]The two letters, dated April 3 and November 17, 1905, are printed in David Block, Baseball Before We Knew It: A Search for the Roots of the Game (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2005), pp. 252-256.[/fn] Spalding must have been overjoyed when he realized that not only had he found an eyewitness account affirming baseball’s American origin, but that its purported inventor grew up to be a military hero in the Civil War![fn]For more on connections between Spalding and Doubleday, see Philip Block, “Abner and Albert, The Missing Link,” Chapter 3 (pp. 32-49) in David Block, Baseball Before We Knew It.[/fn] Lacking anything more substantive or suitable to their inquiry, Spalding and the commission ran with it.

Henry Chadwick passed away only a month after Spalding published his Doubleday blockbuster in March 1908, but there has never been any shortage of challenges to baseball’s singular Creation Myth.[fn]On the creation and debunking of the Doubleday Myth, see Robert W. Henderson, Ball, Bat and Bishop: The Origin of Ball Games (New York: Rockport Press, 1947; reprinted Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2001), pp. 170-194; David Block, Baseball before We Knew It, pp. 32-66; John Thorn, Baseball in the Garden of Eden:The Secret History of the Early Game (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2011), pp. 1-24.[/fn] Elementary fact-checking reveals the future General Doubleday to have been enrolled at West Point at the time of his alleged invention. Graves, we learn, was a man of questionable stability who later shot his wife and died in an asylum. Numerous accounts of earlier baseball activity have since been documented.

There remains a sense, nonetheless, that the old story cannot be wholly without substance. Even in the testimony of a great liar, there is usually some kernel of truth. The Doubleday legend may prove of value despite the shortsighted rubberstamping it received from a stacked jury a century ago, and what Abner Graves witnessed by the banks of Glimmerglass surely deserves a second look.

It was sometime in spring and probably in the year 1840 when a certain Abner Doubleday introduced a novel version of ballplay to his youthful peers.[fn]Graves never pinpointed 1839 as the year of Doubleday’s invention. In his first letter on the subject he said it was “either the spring prior or following the Log Cabin & Hard Cider campaign of General Harrison for President.” In his second letter he said it was “either 1839, 1840 or 1841.” The second letter provides an additional clue. Again referring to President William Henry Harrison, Graves states: “The incident has always been associated in my mind with the Log Cabin and Hard Cider campaign of General Harrison, my father being a Militia Captain and rabid partisan of Old Tippecanoe.”[/fn] It is now known that two persons of that name lived in Cooperstown during Graves’s time there, and it is essential to consider both in trying to make sense of the legend.

The “famous” Abner, son of Ulysses Doubleday, had departed for West Point by September 1838 and was unlikely to have been indulging in idle recreation back in Cooperstown at the time in question. But he had a younger cousin, Abner Demas Doubleday, son of Ulysses’ brother, Demas. Abner Demas was born about six miles north in Pierstown in March 1829,[fn]Record for Abner Demas Doubleday at www.familysearch.org.[/fn] and so would have been 11 years old in spring 1840.

As for our eyewitness, Abner Graves, he was younger yet, having just turned six in February. It is certainly easier to envision him a playmate to the 11-year-old Doubleday than to the 20-year-old future major general.

Graves recalled “several of the best players of sixty years ago,” naming Thomas Bingham, Nelson Brewer, Joseph Chaffee, John Starkweather, and his own cousin John Graves, as well as another Doubleday cousin, John.[fn]Letter of Abner Graves to Beacon Journal of Akron, OH, April 3, 1905.[/fn] But perhaps the most significant other participant was Elihu Phinney, whose family had run a printing business in Cooperstown since the 1790s, and lived on a farm about half a mile up the west side of Lake Otsego. Graves specifically cited the Phinney Farm as a favored location for ballgames.[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

Picture, then, Abner Demas directing a group of these boys, laying out a unique playing field in the meadow at Phinney Farm. Instead of just the two bases — the batter’s home and an out-goal to which he ran — used in the hybrid of Old Cat and Town Ball the Cooperstonians always played, there was now a circuit of four, marked by flat stones set in a diamond shape.[fn]All details concerning the manner of ballplay — both of the old “Town Ball” and the new “Base Ball” — are derived directly from the two letters of Abner Graves cited in footnote 1.[/fn]

To the disappointment of Abner Graves and the other youngest enthusiasts, this new version of ball does not allow for dozens of boys, all ages and sizes, to swarm about, colliding with each other in pursuit of fly hits. There are now but eleven players on the field at a time, in distinctly-assigned positions.

Four spread symmetrically across the outfield. Five man the infield: one at each base, then two extra within the basepaths — one between first base and second; another between second and third.

In their old Town Ball, a “tosser” would stand next to home base, throwing the ball straight upward for the batter to strike upon its fall. Doubleday’s plan puts this player in the center of the diamond, pitching underhand to the batsman. This necessitates a final fielder, the catcher, to stand behind home base and corral stray pitches.

Whereas, in Town Ball, every man tallied runs for himself, and the catcher of a fly ball went to bat no matter how many times he might have already batted, participants now are divided into two teams of equal number and bat in predetermined order. The batter must circle through three bases and reach home again in order to tally for his team.

In a holdover rule, “plugging” a runner with the ball is still good for a put-out. But a proviso declaring a batter out if he swings and misses at three pitches is new to the Cooperstown lads.

The frolic in Cooperstown that so impressed Abner Graves was undoubtedly but one of a myriad of early experiments — variations on a theme of bat and ball and bases. Taking his recollections at face value, however, tells us that the seeds of “The New York Game” were planted in the provinces five years before the Knickerbockers put their rules into writing. Glancing backward to that dim past we have conjured a mental snapshot, depicting a day when our game was very young, very free, and growing with great boyish eagerness toward its maturity.

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Additional Stats

At Phinney Farm along the west side of Lake Otsego, N.Y.

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.