July 1, 1859: Baseball goes to college

Amherst College was founded when Zephania Swift Moore, president of Williams College in Williamstown, in the extreme northwest corner of Western Massachusetts, resigned after a dispute over the school’s isolated location. Moore took 15 students with him and started an institution in the town of Amherst, 60 miles to the east. To this day, Williams students and alumni regard those from the upstart Amherst as renegades, “the Defectors of 1821.”

This made the two schools fit opponents on July 1, 1859, for the first intercollegiate baseball game. The Williams–Amherst game was played by Massachusetts Rules, a wide-open form of the sport commonly known as roundball, in which all ground was fair, runners could be put out by being hit by a thrown ball, and a single out ended each inning. A game consisted of an indeterminate number of frames, since the winning side would be the first to reach a pre-established score.

This made the two schools fit opponents on July 1, 1859, for the first intercollegiate baseball game. The Williams–Amherst game was played by Massachusetts Rules, a wide-open form of the sport commonly known as roundball, in which all ground was fair, runners could be put out by being hit by a thrown ball, and a single out ended each inning. A game consisted of an indeterminate number of frames, since the winning side would be the first to reach a pre-established score.

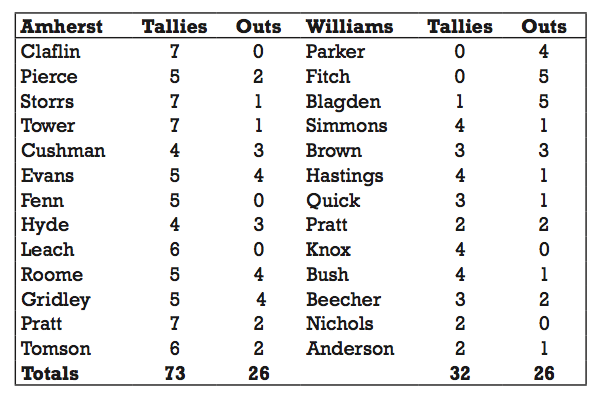

This would explain the lopsided 73-32 trouncing Amherst gave Williams, exceeding the agreed-upon 65-run limit during a 10-run 26th inning. But since the innings were all one-out long, the game, which took 3½ hours to play, in one respect pretty much equaled a modern game. There were only two fewer outs recorded than in a modern nine-inning contest.

The challenge match required considerable negotiation, including a June meeting on neutral ground at a small railside town between the two colleges at which representatives worked out arrangements.[fn]Amherst Express “extra edition,” July 1-2, 1859.[/fn]

A neutral site in Pittsfield, 20 miles from Williamstown, was selected. This was not just a game, but a two-day social event that included a banquet and a chess match between the schools. The Williams student body insisted on the chess match on July 2 to provide “a trial of mind as well as muscle.”[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

In a nice touch, the game site was next to the Maplewood Young Ladies Institute, a finishing school. The Maplewood girls turned out in great numbers, the first clue to their interest being “a silken flag suspended from the balcony of the Institute … intimating that bright eyes would look on the contest.”[fn]Berkshire County Eagle, July 8, 1859.[/fn]

The Amherst student body had been playing ball for at least a year.[fn]George Rugger Cutting, Student Life at Amherst College, Its Organizations, Their Membership and History. (Amherst: Hatch & Williams,) p. 113.[/fn] Although Williams men had also been playing, Amherst was clearly the better prepared. Williams baserunners enthusiastically ran themselves into avoidable outs (half of their 26 outs occurred on the basepaths, as against only seven for Amherst), and “in passing in, they threw too wildly, each where he pleased.”[fn]Amherst Express, July 1-2, 1859.[/fn] In other words, the Williams outfielders missed the cutoff man many times.

The performance of the leadoff batter, Amherst senior James Claflin, was a tipoff to that team’s edge in experience. He hit a first-inning home run on a “back hit,” a tricky variation in which a batter would swing backwards with the flight of the pitched ball, put it into play to the rear, where there were few fielders, and run the bases, since there was no foul territory under Massachusetts rules.

Williams actually scored nine runs in the second inning, but Amherst came back with eight in the third and never then trailed, putting the game away with 12-run bursts in the fourth and 16th innings.

The “science” of batting order formation undoubtedly hadn’t been developed yet, but Amherst, possibly by sheer chance, had its lineup stacked for maximum production. Its first four hitters, Claflin, Edward Pierce, Sam Storrs, and Frank Tower, scored 26 “tallies” and accounted for only four outs, while Williams’ first four made 15 outs and produced only five runs.

Amherst’s “thrower,” Henry Hyde, a sophomore, pitched a complete game with such gusto that a rumor began circulating among the spectators that he was actually a “ringer” of sorts, the college’s blacksmith, since “nobody but a blacksmith could throw in such a fashion for three-and-a-half-hours.”[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

Amherst’s account of the game provided exact specifications for its ball (2.5 ounces in weight and 6.5 inches in circumference) and estimated the Williams ball at about the same.[fn]Ibid.[/fn] A modern-day baseball weighs at least twice that and is about 50 percent larger around. Mathematics and physics dictate that a present-day ball is harder than the balls used in Pittsfield that day. While that was good for the baserunners who were put out by being hit by throws, it would have cut down on the long ball and strong throws from fielders.

Both teams were feted that evening by their Pittsfield hosts, where the Williams players presented their game ball as a trophy to the Amherst team. Both balls are still displayed, side by side, in a glass case at Amherst. The next day Amherst, with Claflin one of its three players, also won the chess match, Williams resigning on the 48th move.

Almost all of the 26 collegians playing in the first game went on to graduate from Amherst, Williams, or some other school. Claflin, the only man to participate in both the baseball and chess competitions, went into education and wound up a high-school principal and state representative in Chicago. Pierce, the first of the three productive hitters behind him, eventually became city administrator and police chief in New Orleans.[fn]Chicago Daily Tribune, October 2, 1891 (Claflin); Obituary Record of Graduates and Non-Graduates of Amherst College for Academic Year Ending June 20, 1917. Amherst: Published by the College, 1917, p. 340 (Pierce).[/fn]

The Civil War was just over history’s horizon as the young men played that day, and at least 11 of them served the Union cause as officers or doctors before war’s end. The Williams starting thrower, Robert Edes Beecher, a nephew of the famous abolitionist preacher Henry Ward Beecher, became a lieutenant colonel in the Union Army.[fn]New York Times, March 29, 1920.[/fn]

One player from each side died in the war. Henry Gridley of Amherst, a lieutenant with a New York infantry regiment, was shot dead on a Georgia battlefield in 1864.[fn]Charles E. Benton, As Seen from the Ranks, A Boy in the Civil War. (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1902,) p. 102.[/fn] George Alanson Parker of Williams became a naval doctor and died on shipboard that same year of a fever contracted from sailors he was treating.[fn]Catalogue of the Sigma Phi. Printed for the Society, 1891, p. 255.[/fn]

Amherst and Williams students continued playing ball, and today they are rivals in the New England Small College Athletic Conference. Along with a third prestigious private college, Wesleyan in Connecticut, they form the Little Three within NESCAC. As the Williams Athletic Department puts it, “There are at least two athletic seasons for each Williams varsity team, the regular season and the Little Three.”[fn]www.athletics.williams.edu/The_Little_Three (accessed April 1, 2011).[/fn]

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Additional Stats

Amherst College vs. Williams College

At Pittsfield, MA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.